Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a high-performance computing library that dramatically speeds up the simulation of complex biological systems, opening doors to virtual organ microenvironment studies.

BioFVM-B leverages parallel computing and optimized data structures to accelerate multiscale simulations using a finite volume method and tridiagonal matrix algorithm.

Scaling agent-based models to simulate complex biological systems remains a significant computational challenge due to the immense number of interactions at the cellular level. This paper, ‘A novel scalable high performance diffusion solver for multiscale cell simulations’, addresses this limitation by introducing BioFVM-B, a high-performance computing library optimized for molecular diffusion modeling in multiscale cell simulations. Through an efficient implementation of the Finite Volume Method and extensive parallelization, BioFVM-B achieves up to a 200x speedup and 36% memory reduction compared to existing solutions. Will this advancement unlock the potential for truly predictive, whole-organ simulations and accelerate the development of personalized digital twins for disease modeling?

The Illusion of Control: Modeling Biological Chaos

Biological processes aren’t isolated events; they are deeply interwoven with the surrounding microenvironment, a complex matrix of signaling molecules, nutrients, and physical cues. Understanding how cells interact with, and are shaped by, this environment is therefore fundamental to deciphering everything from embryonic development and immune responses to cancer progression and wound healing. These interactions aren’t simply about proximity; cells actively modify their surroundings, creating feedback loops and gradients that influence behavior. For example, a tumor cell doesn’t just grow in a static space – it alters the local pH, consumes oxygen, and releases growth factors, impacting neighboring cells and the surrounding tissue. Consequently, any attempt to model biological systems must account for this reciprocal relationship, recognizing the microenvironment not as a passive backdrop, but as an active participant in the unfolding biological drama. Ignoring this interplay risks producing incomplete, and potentially misleading, representations of reality.

Computational modeling of biological systems increasingly requires simulating the interactions between cells and their surrounding microenvironment, yet current methods face significant scalability challenges. Traditional approaches, often reliant on finite element or finite difference methods, become computationally prohibitive when applied to large-scale systems or extended timescales. This limitation stems from the need to resolve spatial gradients of signaling molecules and nutrients across numerous cells, demanding ever-increasing computational power and memory. Consequently, researchers are often forced to simplify their models, reducing the number of cells, limiting the duration of simulations, or making assumptions about homogeneity-all of which can compromise the biological realism and predictive power of the results. This bottleneck hinders progress in fields like cancer biology, developmental biology, and immunology, where understanding the nuanced interplay between cells and their environment is paramount.

The accurate depiction of substrate dynamics is fundamental to modeling cellular microenvironments, yet the computational cost associated with simulating these processes presents a significant hurdle. Specifically, the ‘Diffusion-Decay Process’ – which governs how nutrients and signaling molecules are transported and consumed by cells – is exceptionally resource-intensive. This process requires tracking the concentration of each substrate across both space and time, necessitating the solution of partial differential equations for every constituent. As biological systems often involve numerous substrates and complex geometries, the number of calculations escalates rapidly, quickly overwhelming even high-performance computing resources. Consequently, researchers frequently resort to simplifications or limitations in model scale, potentially compromising the biological accuracy needed to fully understand cellular behavior and interactions. Addressing this computational bottleneck is therefore critical for advancing in silico studies of complex biological systems.

PhysiCell and BioFVM: A Framework Built on Compromises

The PhysiCell platform is a software framework enabling physics-based modeling of cellular processes across multiple spatial and temporal scales. It integrates computational methods for simulating cell behavior, including mechanics, biochemistry, and motility, within a three-dimensional microenvironment. PhysiCell utilizes a modular design, allowing researchers to customize and extend the platform with user-defined models and data. The environment supports a range of simulation scenarios, from single-cell studies to complex tissue-level simulations, and is designed to facilitate quantitative predictions of cellular responses to various stimuli and conditions. PhysiCell’s architecture is optimized for parallel computing, enabling efficient simulations of large-scale biological systems.

BioFVM is a finite volume method library integrated within the PhysiCell framework to numerically solve reaction-diffusion equations governing the transport and consumption of signaling molecules, nutrients, and waste products in the extracellular space. It calculates the spatial and temporal distribution of these substrates based on parameters defining diffusion coefficients, reaction rates, and decay constants. The library employs a cell-centered finite volume approach, discretizing the simulation domain into a grid of control volumes surrounding each cell, and solving for the concentration of each substrate within these volumes using explicit or implicit time-stepping schemes. BioFVM supports both 2D and 3D simulations and allows for the incorporation of complex geometries to accurately represent the cellular microenvironment.

The Level-of-Detail (LOD) method within BioFVM reduces computational demands by adaptively adjusting the simulation resolution based on spatial gradients of the diffusing species. Instead of solving the diffusion equation on a uniform, high-resolution grid throughout the entire domain, the LOD method employs a hierarchical grid structure. Regions with steep concentration gradients are simulated with a finer mesh, while areas with minimal change utilize a coarser mesh. This dynamic adjustment minimizes the number of grid points requiring calculation at each time step, significantly improving simulation speed, particularly for large domains or long simulation times. The method accurately approximates the solution to the diffusion equation [latex]\nabla \cdot (D \nabla c) = R [/latex], where [latex]c[/latex] is concentration, [latex]D[/latex] is the diffusion coefficient, and [latex]R[/latex] represents sources and sinks, while drastically reducing computational cost compared to traditional finite difference or finite element methods applied uniformly.

Scaling the Inevitable: BioFVM-X and BioFVM-B

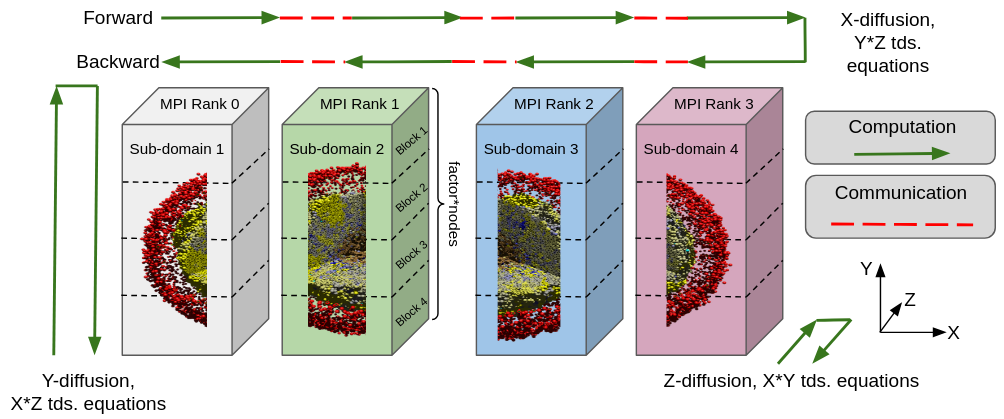

BioFVM-X represents an advancement over the original BioFVM by incorporating distributed simulation capabilities. This functionality enables the partitioning of a computational problem across multiple processing units, effectively increasing the scale and complexity of models that can be accurately simulated. By distributing the workload, BioFVM-X overcomes limitations imposed by single-processor memory and computational resources, allowing for the modeling of larger biological systems and more detailed physiological processes than previously feasible with BioFVM. This scalability is achieved through techniques like data decomposition, which divide the simulated domain for parallel processing.

Data decomposition in BioFVM-X involves partitioning the overall computational domain – representing the biological system being modeled – into smaller, independent subdomains. Each subdomain is then assigned to a separate processing unit, allowing for concurrent computation. This approach facilitates parallel processing by minimizing inter-process communication and maximizing computational throughput. The decomposition strategy employed is crucial for scalability; effective decomposition balances workload distribution and minimizes the amount of data that needs to be exchanged between processing units to ensure accurate simulation results. This allows BioFVM-X to address significantly larger and more complex biological systems than were previously feasible with single-processor simulations.

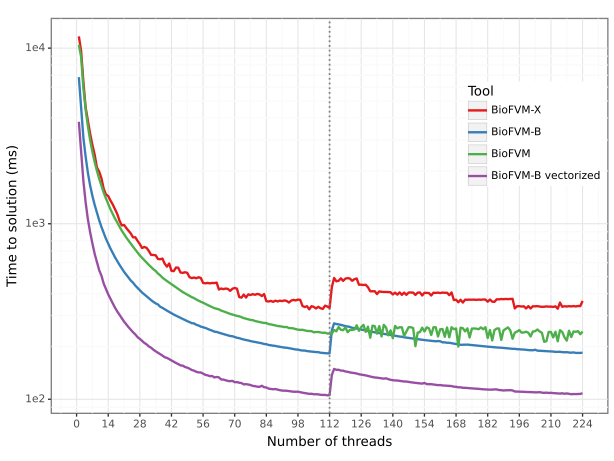

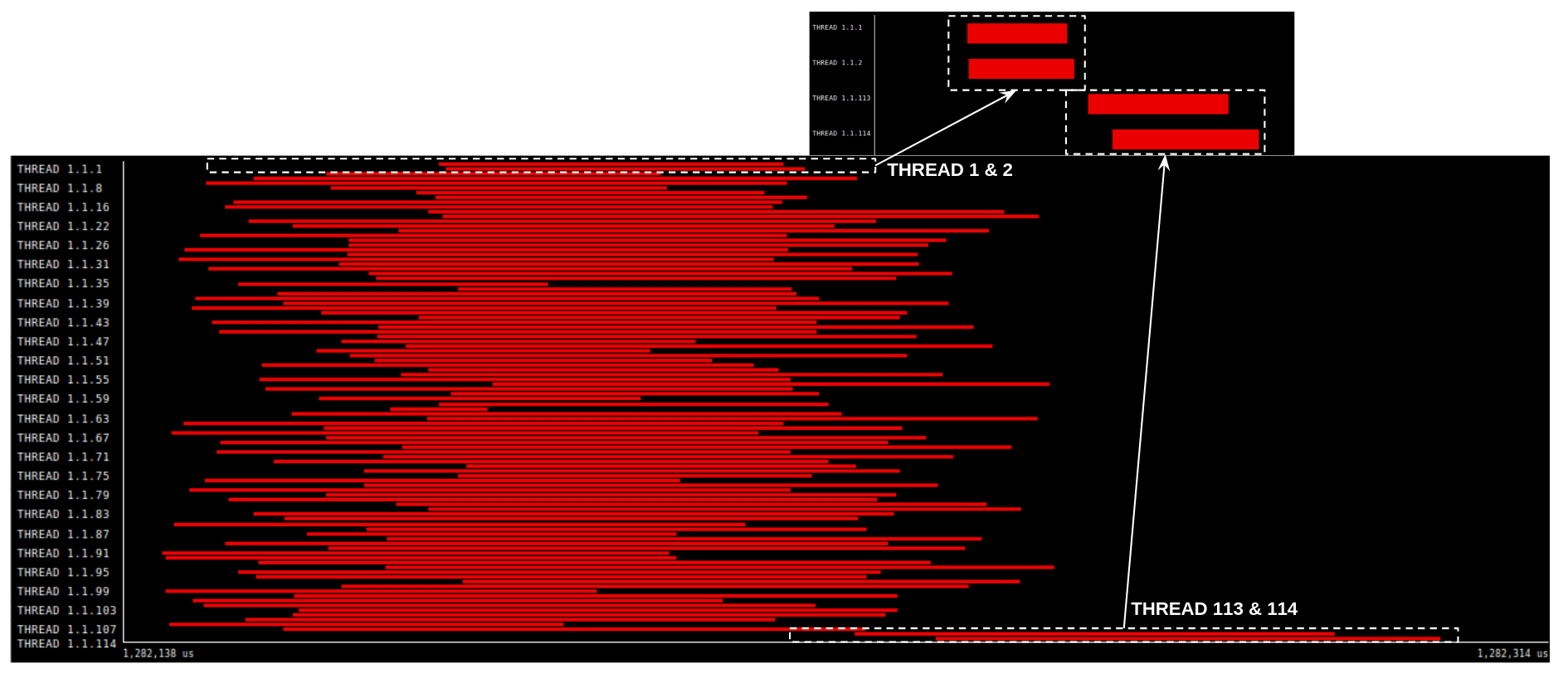

BioFVM-B represents a significant advancement in computational performance by utilizing high-performance computing techniques. This solution implements parallel programming models, specifically Message Passing Interface (MPI) and OpenMP, to distribute computational workload across multiple processing units. MPI facilitates communication and data exchange between these units, while OpenMP enables shared-memory parallelism within a single node. This combined approach allows BioFVM-B to efficiently solve complex biological simulations, achieving substantial speedups compared to previous iterations of the BioFVM platform.

Performance optimizations in BioFVM-B are significantly achieved through the implementation of Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) instructions and vectorization techniques. These methods enable parallel execution of operations on multiple data points with a single instruction, substantially reducing the number of instructions the processor needs to execute. Specifically, vectorization transforms scalar operations into vector operations, allowing the processor to perform the same operation on multiple data elements simultaneously. This approach exploits data-level parallelism, leading to a marked increase in computational throughput and a corresponding reduction in execution time for computationally intensive tasks within the simulation.

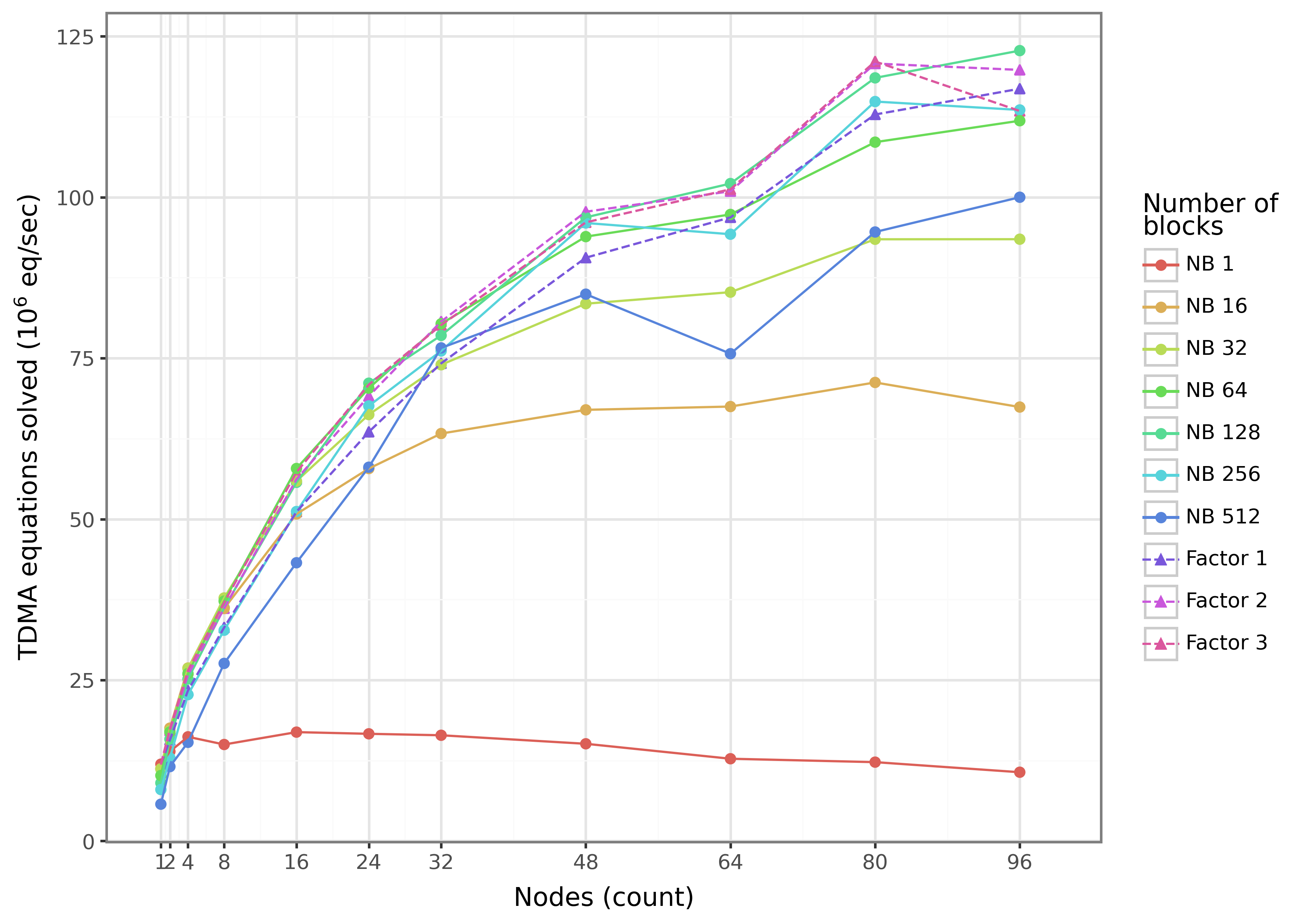

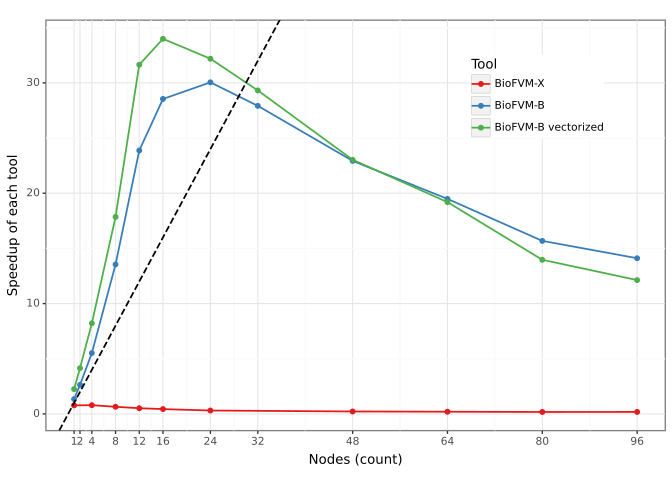

In the largest test case, BioFVM-B demonstrated significant performance improvements over prior versions. Specifically, BioFVM-B achieved a 196.8x speedup compared to BioFVM-X and a 34.8x speedup over the original BioFVM. This benchmark involved simulating 21% of a mammalian liver, indicating the scalability of BioFVM-B to handle computationally intensive, biologically relevant models. These speedups were achieved through implementation of parallel programming models and optimized code execution.

The Illusion of Progress: Validating Scalability and Beyond

Determining parallel efficiency is paramount when tackling increasingly complex biological simulations, and BioFVM-B’s performance is rigorously evaluated using a metric known as weak scaling. This process assesses the simulation’s ability to maintain consistent performance-specifically, computational time-even as both the problem size and the number of processors utilized are increased proportionally. Effectively, weak scaling reveals whether adding more computational resources translates into a corresponding ability to handle larger, more detailed biological models without sacrificing speed. A successful demonstration of weak scaling signifies that BioFVM-B can efficiently leverage parallel computing architectures, opening doors to investigations of biological systems at scales previously deemed computationally intractable and ultimately accelerating scientific discovery.

BioFVM-B’s architecture fundamentally shifts the boundaries of biological simulation by efficiently distributing computational demands across multiple processors. This parallel processing capability enables researchers to model biological systems with unprecedented detail and complexity, moving beyond the limitations of traditional single-processor approaches. Previously intractable problems – such as simulating the metabolic interactions within an entire tumor microenvironment or tracking the behavior of individual cells within a developing tissue – now become accessible. The ability to explore these larger, more realistic scales provides a more comprehensive understanding of biological processes and facilitates the investigation of emergent behaviors that would be missed in smaller-scale simulations, ultimately accelerating discoveries in fields ranging from cancer research to regenerative medicine.

To ensure simulations accurately reflect biological reality, BioFVM-B employs a [latex]\text{Gaussian distribution}[/latex] when defining the initial concentration of substrates within the modeled environment. This approach moves beyond simplistic, uniform starting conditions by acknowledging that substrates are rarely, if ever, evenly distributed in living systems. By modeling initial densities with a bell-shaped curve – characterized by a mean and standard deviation – the system replicates the more nuanced and statistically probable distribution of nutrients or signaling molecules. Consequently, the resulting simulations are more representative of in vivo conditions, leading to greater confidence in the predicted behaviors of cells and tissues, and providing a more robust foundation for interpreting complex biological phenomena.

A significant advancement in computational efficiency is demonstrated by BioFVM-B, achieving substantial memory reductions compared to its predecessor, BioFVM-X. When simulating biological processes involving a single substrate, BioFVM-B requires 40% less memory, allowing for larger and more complex models to be explored within the same computational constraints. Even with simulations incorporating 32 substrates – a scenario demanding considerably more resources – BioFVM-B maintains a noteworthy 15% reduction in memory usage. This enhanced efficiency isn’t merely incremental; it directly translates to the ability to investigate biological systems at scales previously unattainable, opening doors for more detailed and comprehensive simulations in fields ranging from cancer research to regenerative medicine.

The enhanced computational efficiency of BioFVM-B is poised to reshape investigations into intricate biological processes, particularly within the fields of cancer biology and tissue engineering. Reduced memory demands and improved scalability allow researchers to model larger, more realistic systems – from the complex tumor microenvironment and metastatic spread to the dynamic processes of tissue regeneration and wound healing. This capability facilitates the exploration of previously intractable questions concerning cellular interactions, signaling pathways, and the impact of spatial heterogeneity on disease progression and therapeutic response. Consequently, the platform promises to accelerate the pace of discovery, enabling the design of more effective targeted therapies and innovative regenerative medicine strategies.

The pursuit of scalable simulations, as demonstrated by BioFVM-B, inevitably invites a reckoning with complexity. The library optimizes data structures and parallel computing to model entire organ microenvironments, a feat of engineering born from compromise. As Linus Torvalds once observed, “Most developers think lots of planning is good, and that’s almost always wrong.” BioFVM-B isn’t an exercise in pristine architecture; it’s a pragmatic response to the realities of multiscale modeling. Every optimization, while necessary to achieve performance, introduces a new surface for entropy. The code doesn’t reflect ideals, but the scars of battles fought against the limitations of hardware and the unforgiving demands of production.

Where Do We Go From Here?

BioFVM-B, like all attempts to model biological systems, delivers a performance boost. It’s a faster way to generate data, not necessarily more meaningful data. The core challenge remains: validation. These multiscale simulations create beautifully detailed microenvironments, but connecting the in-silico world to actual cellular behavior will continue to be a bottleneck. If a system crashes consistently, at least it’s predictable. These things rarely do.

The inevitable next step involves ‘integration’ – bolstering BioFVM-B with even more complex biophysical models. Expect a corresponding increase in computational demand, and a renewed search for algorithmic shortcuts. It’s a familiar pattern. The ‘cloud-native’ label will appear, promising scalability, but in reality, it’s just the same mess, just more expensive. The truly interesting work will lie in error analysis – figuring out why the simulations diverge from reality, and quantifying the uncertainty.

Ultimately, this library, and others like it, are less about solving biology, and more about leaving notes for digital archaeologists. Each iteration refines the model, but the fundamental limitation persists: the system is vastly more complicated than anything we can currently represent. And that’s alright. It gives the next generation something to debug.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05017.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Brent Oil Forecast

2026-02-08 19:09