Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages physical laws to unlock causal relationships hidden within complex, changing data streams.

This review presents a framework for causal discovery from non-stationary time series data by incorporating known physics-expressed as ordinary differential equations-into stochastic differential equation models, offering theoretical identifiability guarantees and empirical validation.

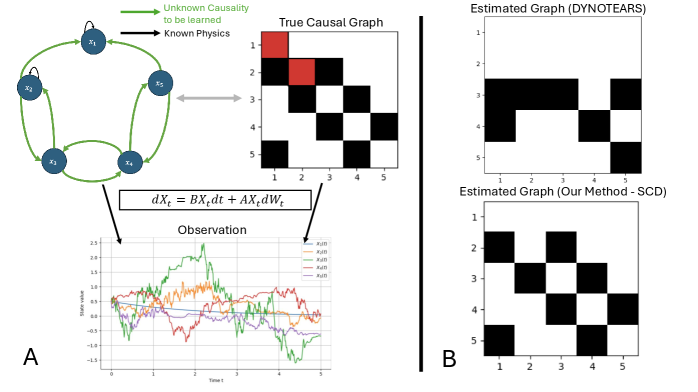

Identifying causal relationships in complex dynamical systems is often hampered by the challenges of non-stationarity and feedback loops, limiting the performance of purely data-driven approaches. This work, ‘Physics as the Inductive Bias for Causal Discovery’, addresses this limitation by integrating known physical laws-expressed as ordinary differential equations-into a stochastic differential equation framework. By leveraging physics as an inductive bias, we develop a method with theoretical guarantees for recovering the underlying causal graph and demonstrate improved performance on non-stationary time series data compared to state-of-the-art baselines. Can this physics-informed approach unlock more robust and interpretable causal models for a wider range of real-world systems?

The Evolving Landscape of Causation

Establishing definitive cause-and-effect relationships is a cornerstone of scientific understanding, yet rigorously controlled experiments, traditionally considered the gold standard, frequently present substantial hurdles when applied to intricate systems. The logistical and financial costs associated with randomized controlled trials can be prohibitive, particularly in fields like epidemiology or climate science where manipulating variables at scale is simply not feasible. Moreover, ethical considerations often preclude interventions that might be necessary to isolate causal effects in human populations. For example, deliberately exposing individuals to harmful conditions to assess preventative measures is ethically untenable. Consequently, researchers are increasingly compelled to leverage the wealth of passively collected observational data, despite the inherent difficulties in disentangling correlation from causation within these complex, often uncontrolled, datasets.

The proliferation of passively collected data presents a paradox: while vast amounts of information are readily available, discerning cause-and-effect relationships within it remains a significant challenge. Unlike controlled experiments that manipulate variables, observational data simply records what is, leaving researchers to untangle the web of correlations and confounding factors that obscure true causality. These confounders – variables influencing both the presumed cause and effect – can create spurious associations, leading to incorrect conclusions. Consequently, sophisticated statistical and machine learning techniques, such as instrumental variables, propensity score matching, and causal Bayesian networks, are crucial for attempting to isolate causal effects and move beyond mere correlation. Successfully leveraging observational data requires not just computational power, but also careful consideration of potential biases and a robust theoretical framework to guide the analysis and interpretation of results.

Current methods for discerning cause and effect often falter when faced with the complexity of real-world datasets, which frequently contain numerous variables and intricate relationships. This difficulty stems from the ‘curse of dimensionality’, where the number of potential causal connections explodes with each added variable, overwhelming statistical analysis. Furthermore, these approaches typically treat data as a ‘black box’, neglecting valuable insights from existing scientific understanding. Effectively incorporating prior mechanistic knowledge – such as known biological pathways or physical laws – is crucial for guiding causal inference and reducing the search space, but remains a significant challenge. Bridging this gap between data-driven discovery and established theory is essential for unlocking reliable causal insights from complex, high-dimensional systems and moving beyond mere correlation.

![Our approach leverages known mechanistic dynamics [latex] ext{(Hes1 system)}[/latex] as a prior while learning the underlying causal structure and any additional variables necessary to fully explain the system.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.04907v1/Fig/Motivation.png)

Modeling Systems in Flux: A Mechanistic Approach

SDE-Based Causal Discovery utilizes Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) to represent and infer causal relationships between variables. This approach frames causal mechanisms as dynamic systems governed by [latex]dx_t = \mu(x_t)dt + \sigma(x_t)dW_t[/latex], where [latex]x_t[/latex] represents the state of a variable at time t, [latex]\mu(x_t)[/latex] defines the deterministic drift, and [latex]\sigma(x_t)dW_t[/latex] represents the stochastic diffusion term. By formulating causal inference as a problem of estimating the parameters of these SDEs, the method moves beyond traditional structural equation models to allow for continuous-time dynamics and the explicit modeling of noise processes. This framework enables the identification of causal links by analyzing how changes in one variable’s SDE parameters propagate through the system and affect other variables, even in the presence of feedback loops and latent confounders.

The SDE-based causal discovery framework leverages the ‘Drift Term’ within the Stochastic Differential Equation to incorporate established mechanistic knowledge. This term, [latex] \mu(X) [/latex], mathematically defines the deterministic component of the system’s dynamics, directly representing known relationships between variables. By explicitly defining [latex] \mu(X) [/latex] based on prior scientific understanding or domain expertise, the method constrains the causal search space and improves the accuracy of inferred relationships. This integration of prior knowledge is crucial for identifying causal links in complex systems where observational data alone may be insufficient or ambiguous, and allows researchers to test hypotheses embedded within the mechanistic model.

The diffusion term within the Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) framework explicitly accounts for unmodeled couplings and inherent uncertainty present in the system. This term, mathematically represented as a Wiener process multiplied by a diffusion coefficient σ, introduces stochasticity and allows for deviations from the deterministic dynamics defined by the drift term. By incorporating this noise component, the model avoids overconfidence in predictions and provides a more realistic representation of complex systems where complete knowledge of all influencing factors is often unavailable. The magnitude of σ reflects the degree of uncertainty, and its inclusion is crucial for model robustness when facing incomplete or noisy observational data.

Validating the Framework: Performance and Accuracy

The Euler-Maruyama discretization method is utilized to numerically solve the Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) as obtaining an analytical solution is often intractable. This method approximates the continuous-time SDE by a discrete-time process, enabling computation via iterative updates. Given an SDE of the form [latex] dX_t = f(X_t, t)dt + g(X_t, t)dW_t [/latex], where [latex] W_t [/latex] is a Wiener process, the Euler-Maruyama method approximates the solution at time [latex] t_{k+1} [/latex] as [latex] X_{k+1} = X_k + f(X_k, t_k)\Delta t + g(X_k, t_k)\sqrt{\Delta t}Z_{k+1} [/latex], with [latex] Z_{k+1} \sim N(0, 1) [/latex] and [latex] \Delta t [/latex] representing the time step. This approach provides a computationally feasible method for simulating the dynamics described by the SDE, crucial for subsequent causal graph estimation.

Graph Lasso is utilized for causal graph estimation from the discretized Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) due to its capacity to impose sparsity on the estimated adjacency matrix. This is achieved through an [latex]L_1[/latex] regularization term added to the least squares objective function, encouraging many edge weights to be driven to zero. The resulting sparse graph facilitates interpretability by highlighting the most significant direct causal relationships while mitigating the impact of noise and spurious correlations. The regularization parameter is tuned via cross-validation to balance model fit and sparsity, ultimately yielding a parsimonious representation of the underlying causal structure.

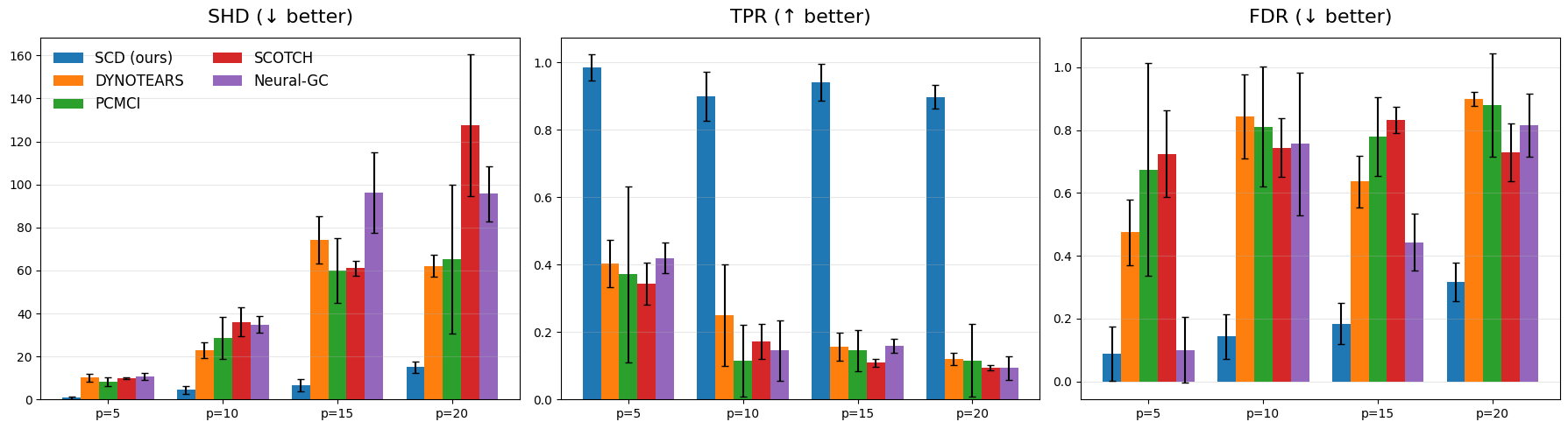

Performance validation utilized the True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Discovery Rate (FDR) as key metrics to assess the accuracy of causal graph recovery. Comparative analysis against established methods – DYNOTEARS, PCMCI, SCOTCH, and Neural-GC – across multiple datasets demonstrated improvements in performance. Specifically, the framework achieved lower Structural Hamming Distance (SHD) scores, indicating a reduced difference between the recovered graph and the ground truth, and thus improved accuracy in identifying causal relationships. Lower SHD values consistently indicated superior graph recovery capabilities compared to the baseline methods tested.

Beyond Correlation: Implications for System Understanding

A cornerstone of accurately discerning cause-and-effect relationships within complex systems lies in the ‘Incoherence Condition’. This principle fundamentally ensures that causal effects are not masked or confounded by the intricate web of interactions within the data. Specifically, it postulates that no variable can be simultaneously highly correlated with both a cause and an effect, thereby preventing ambiguity in the estimated causal relationships. Without this condition, it becomes impossible to uniquely determine the direction of influence between variables, leading to potentially misleading conclusions. The Incoherence Condition, therefore, acts as a critical prerequisite for reliable causal inference, guaranteeing that the observed data genuinely reflects the underlying causal structure and allowing for the unambiguous identification of true causal effects, even in the presence of substantial noise and complexity.

A crucial aspect of this framework lies in its utilization of Lyapunov Stability, a mathematical principle borrowed from dynamical systems theory. This principle offers a rigorous guarantee that the estimated causal graph will not fluctuate wildly with incoming data, but rather converge to a stable representation of the underlying causal relationships. Essentially, Lyapunov Stability ensures that any initially estimated connections are not merely artifacts of the specific dataset, but reflect genuine dependencies in the system. This is achieved by demonstrating that the estimated graph settles into a state where small perturbations-noise or minor changes in the data-do not lead to drastic alterations in the overall structure. By preventing the emergence of spurious connections, Lyapunov Stability significantly enhances the reliability and interpretability of the discovered causal model, making it a robust tool for understanding complex systems over time.

The efficiency of this causal discovery framework is significantly enhanced by leveraging sparsity assumptions – the principle that most variables are only weakly connected, resulting in a simplified causal graph. This simplification isn’t merely aesthetic; it directly translates to reduced computational demands and improved statistical power. Importantly, researchers have established a quantifiable relationship between graph sparsity and the necessary sample size for accurate inference. Specifically, the analysis demonstrates that a number of samples, denoted as n, must satisfy [latex]n≳Cc~max{log(p)|pa(i)3|,|pa(i)4}[/latex], where p represents the total number of variables and [latex]pa(i)[/latex] indicates the parents of the i-th variable. This bound highlights that the required sample size grows with the complexity of the causal relationships – particularly the maximum degree of any node – but remains manageable thanks to the inherent sparsity of the modeled system.

The pursuit of causal structures from time-series data, as explored in this work, inherently acknowledges the relentless march of time and its impact on systems. Each observation represents a fleeting moment, a snapshot within a continuous evolution. Brian Kernighan aptly observes, “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” This sentiment resonates with the challenges of discerning causality in non-stationary environments; clever models must account for the inevitable decay and transformation of underlying mechanisms. The framework proposed here, by incorporating known physics, attempts to impose a structure that resists complete entropy, allowing for more graceful aging of the causal model and a more robust recovery of the true underlying relationships.

What Lies Ahead?

The integration of physics as an inductive bias, as demonstrated, does not resolve the fundamental tension inherent in causal discovery: every failure is a signal from time. While this work offers a pathway to improved identifiability in non-stationary systems, the assumption of known physics is itself a limitation. The universe rarely offers its secrets without ambiguity; future work must grapple with imperfect or incomplete physical models, exploring methods to learn these constraints directly from data-a dialogue with the past, if you will-rather than impose them.

Furthermore, the current framework relies on stochastic differential equations. The choice of this mathematical language, while powerful, is not universal. Other formulations-discrete-time models, agent-based simulations, or even entirely new mathematical structures-may prove more suitable for capturing the nuances of complex systems. The search for a truly general theory of causal discovery, one that transcends specific mathematical representations, remains a distant, perhaps asymptotic, goal.

Ultimately, the longevity of any such framework will not be measured by its immediate successes, but by its capacity to degrade gracefully. Systems evolve, data shifts, and assumptions are inevitably violated. The true test lies not in achieving perfect causal graphs, but in building models that reveal how and why they fail-for in those failures lie the seeds of future understanding.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04907.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- Brent Oil Forecast

2026-02-06 22:06