Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research shows that training whole-brain simulations with a biologically-inspired learning strategy significantly improves their ability to generalize and predict individual cognitive traits.

![Biology-informed optimization of parameters consistently yields solutions-evidenced by [latex]R^2[/latex] values exceeding chance levels as determined through 10,000 permutations-that robustly predict behavioral traits across distinct resting-state networks, including fluid reasoning ability, inwardly directed problems, and outwardly directed problems, as quantified by associated <i>p</i>- and <i>q</i>-values.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11398v1/x3.png)

Hierarchy-informed evolutionary optimization of Dynamic Mean Field Models enables improved cross-subject generalization and behavioral prediction.

Optimizing large-scale biophysical brain models is challenging due to the high dimensionality and nonlinearity of parameter spaces, often leading to overfitting and limited predictive power. This limitation is addressed in ‘Evolution With Purpose: Hierarchy-Informed Optimization of Whole-Brain Models’, which investigates whether incorporating biological knowledge can improve model generalization. By guiding an evolutionary optimization strategy with the known hierarchical organization of brain regions-specifically using Dynamic Mean Field models-researchers demonstrated significantly improved cross-subject prediction of behavioral abilities. Does this approach-harnessing domain expertise to shape optimization algorithms-represent a broader pathway toward building more robust and interpretable models in complex scientific domains?

The Imperative of Biophysical Fidelity in Neural Modeling

Many computational models in neuroscience, while valuable for exploring broad principles, often sacrifice biological realism for mathematical tractability. These simplified approaches frequently represent neurons as point-like entities or employ highly abstracted network structures, neglecting the intricate morphology of neurons, the diversity of ion channels, and the complex interplay of synaptic transmission. This lack of biophysical detail can limit the ability of these models to accurately capture the rich dynamics observed in the brain, such as oscillations, bursting, and synaptic plasticity. Consequently, predictions derived from such models may not fully translate to experimental observations, hindering a deeper understanding of how neural circuits give rise to cognitive function and behavior. The challenge lies in bridging the gap between computational efficiency and biological fidelity to create models that are both tractable and capable of capturing the essential features of brain dynamics.

Current cognitive neuroscience frequently operates with a disconnect between high-level descriptions of mental processes and the biological realities of brain function. While abstract models can successfully predict behavioral outcomes, they often lack the crucial link to the underlying neural mechanisms responsible for functional connectivity – how different brain regions interact and coordinate activity. This gap hinders a complete understanding of cognition, as behavioral predictions without neural grounding remain largely descriptive rather than explanatory. Effectively bridging this divide requires investigations into how specific neuronal properties, synaptic transmission, and network architectures give rise to observed patterns of functional connectivity, ultimately allowing for a more mechanistic and predictive understanding of the brain’s computational capabilities.

The future of computational neuroscience hinges on a fundamental shift towards whole-brain modeling, demanding simulations deeply rooted in biophysical principles. Current approaches often abstract away crucial neural details, limiting their ability to accurately reflect the brain’s intricate functionality; however, increasingly sophisticated models now integrate factors such as neuron morphology, synaptic dynamics, and the complex interplay of ion channels. These biophysically realistic simulations aren’t merely about increasing detail – they allow researchers to explore how neural mechanisms give rise to macroscopic brain activity and cognitive function. By simulating the brain at a scale that incorporates these biological constraints, scientists can move beyond correlative studies and begin to establish causal links between neural activity and behavior, ultimately leading to a more comprehensive understanding of brain function and disease.

A Mean Field Approximation: Balancing Realism and Tractability

The Dynamic Mean Field Model (DMFM) approximates the collective behavior of large populations of interacting neurons using a set of deterministic differential equations, known as mean-field equations. Rather than simulating individual neuron activity, the DMFM focuses on the average activity levels and statistical properties of neuronal populations. These equations typically describe the evolution of quantities such as the mean membrane potential [latex]V[/latex], the average synaptic current [latex]I[/latex], and the population firing rate [latex]r[/latex]. Crucially, the model incorporates essential biophysical properties including synaptic conductances, neuronal input resistance, and refractory periods to provide a biologically plausible representation of neural dynamics. This approach significantly reduces computational cost compared to simulating individual neurons while still capturing key features of brain activity, such as oscillations and bistability.

Parameter optimization within the Dynamic Mean Field Model is a computationally intensive process necessitated by the model’s numerous free parameters which govern neuronal properties and connectivity. Achieving accurate reflection of observed brain activity, such as that derived from fMRI or EEG data, requires iterative adjustment of these parameters – including synaptic weights, neuronal thresholds, and conductance densities – to minimize the discrepancy between simulated and empirical data. Optimization algorithms employed typically involve gradient-based methods or evolutionary strategies applied to a cost function quantifying this discrepancy. The high dimensionality of the parameter space, coupled with potential non-convexity of the cost function, often necessitates the use of global optimization techniques and substantial computational resources to prevent convergence to local minima and ensure a robust fit to the observed data. Furthermore, parameter identifiability – the degree to which unique parameter values can be estimated – poses a challenge, requiring careful consideration of model structure and data constraints.

The Dynamic Mean Field Model incorporates data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) to refine and assess the accuracy of its simulations. Specifically, HCP data, including resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and diffusion MRI, provides constraints on model parameters related to cortical connectivity, excitatory and inhibitory coupling strengths, and the distribution of neuronal populations. Validation involves comparing model-generated activity patterns – such as spontaneous fluctuations in cortical activity and responses to simulated stimuli – with the empirical data obtained from HCP subjects. This comparison utilizes metrics like correlation coefficients and spectral analysis to quantify the similarity between modeled and observed brain dynamics, allowing for iterative model refinement and ensuring biological plausibility.

Lyapunov stability is a critical requirement for validating the Dynamic Mean Field Model (DMFM) because it mathematically guarantees that simulated neural dynamics will not diverge from realistic behavior. Specifically, Lyapunov stability ensures that, given a small perturbation to the system’s initial state, the system will return to a stable equilibrium point or limit cycle, mirroring the bounded activity observed in biological neural networks. Verification typically involves demonstrating that the largest eigenvalue of the Jacobian matrix evaluated at the equilibrium point is negative, confirming asymptotic stability. Failure to satisfy Lyapunov criteria indicates the model may produce unrealistic, unbounded activity, rendering its predictions unreliable and necessitating adjustments to the model’s parameters or structure to ensure biological plausibility.

Curriculum Learning: Guiding Optimization in a Complex Landscape

The Dynamic Mean Field Model (DMF) presents a significant optimization challenge due to the high dimensionality and non-convexity of its parameter space. This complexity arises from the numerous interacting parameters required to define the model’s behavior, leading to a landscape with many local optima and saddle points. Traditional optimization algorithms, such as stochastic gradient descent, can become trapped in these local minima or exhibit slow convergence due to the difficulty of navigating this complex space. The sheer number of parameters-often exceeding hundreds or thousands-further exacerbates the problem, increasing the computational cost of evaluating the objective function and hindering efficient exploration of the parameter space. Consequently, standard optimization techniques frequently fail to identify parameter configurations that yield optimal or even satisfactory model performance.

Curriculum Learning addresses the challenges posed by complex parameter spaces in models like the Dynamic Mean Field Model by strategically sequencing the introduction of parameters during optimization. Rather than presenting all parameters simultaneously, this approach begins with simpler, more easily optimized parameters, gradually increasing complexity as the model learns. This guided optimization process aims to avoid local optima and accelerate convergence by providing a more stable learning trajectory. The order of parameter introduction is not random; it is determined by factors such as parameter sensitivity or estimated contribution to overall model performance, allowing the model to build a foundational understanding before tackling more nuanced adjustments.

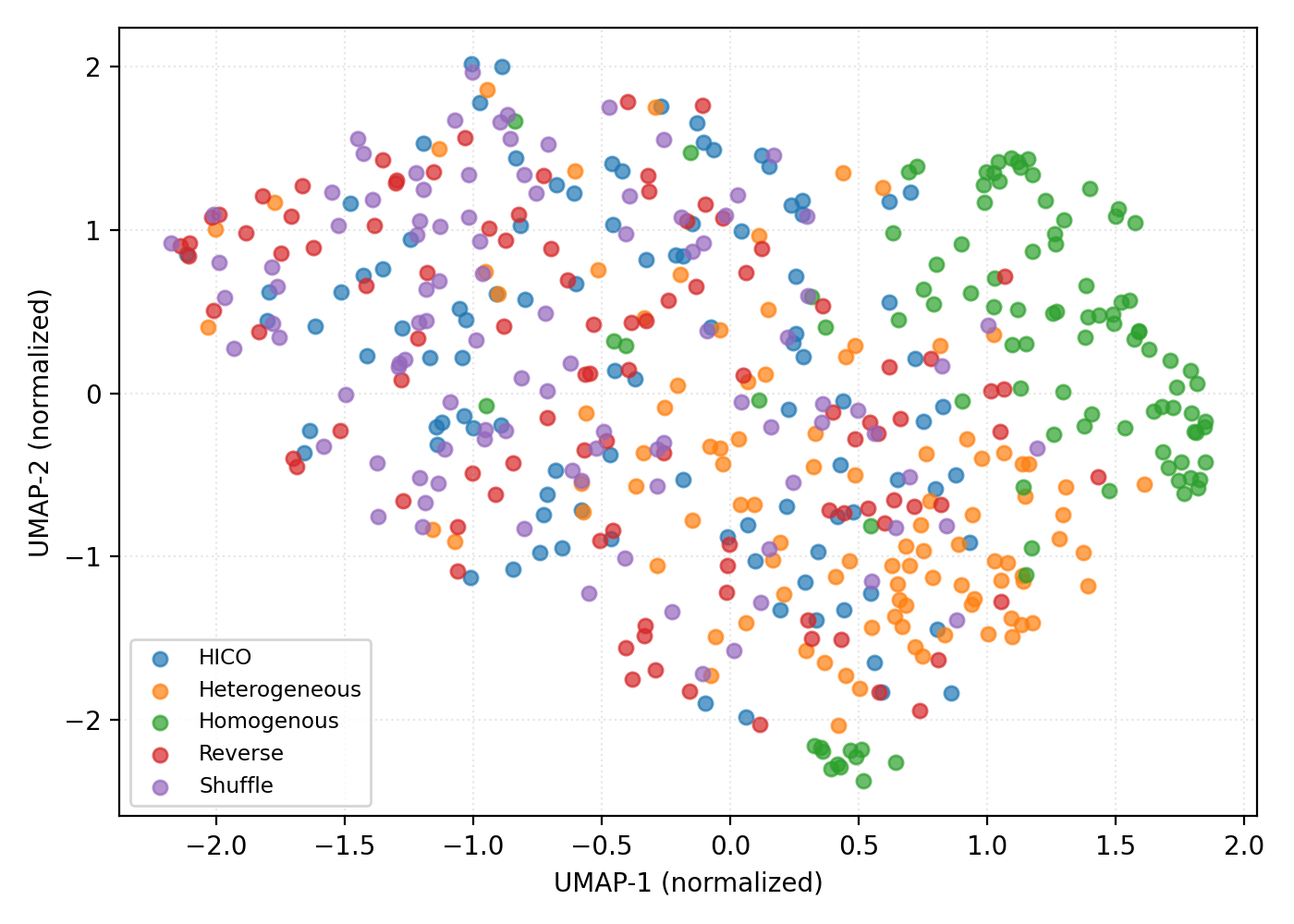

The investigation into curriculum learning strategies encompassed a range of approaches, beginning with Shuffled Curriculum, which served as a control by presenting parameters in a randomized order. More advanced techniques included Reverse-Phased Curriculum, designed to initially train on samples closer to the optimal solution and progressively increase difficulty, and Hierarchy-Informed Curriculum, which leveraged the known hierarchical structure of the Dynamic Mean Field Model’s parameter space to guide the training sequence. These methods were evaluated based on their ability to improve optimization efficiency and final model fitness, with the goal of overcoming the challenges posed by the model’s complex parameter landscape.

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction was implemented to visualize the high-dimensional parameter space of the Dynamic Mean Field Model during optimization. This visualization allowed for qualitative assessment of how different curriculum learning strategies navigated this space. Quantitative analysis revealed statistically significant improvements in model fitness for both the Hierarchy-Informed Curriculum (HICO) and reverse-phased curriculum learning strategies when compared to the shuffled baseline. Specifically, statistical tests yielded p-values ranging from < 10-23 to < 10-25, indicating a very low probability of observing the obtained fitness improvements by chance, and supporting the efficacy of these curriculum learning approaches.

From Simulation to Predictive Insight: Bridging the Gap to Behavior

The optimized parameters of a trained Dynamic Mean Field Model offer a novel pathway for predicting individual behavioral traits. This approach moves beyond simply simulating brain activity; it leverages the model’s internal state – as defined by its optimized parameters – as direct indicators of complex behaviors. Essentially, the model learns to represent the underlying neural mechanisms associated with specific behaviors, and these learned representations are encoded within the parameter values. By mapping these parameters to established behavioral measures, researchers can predict an individual’s tendencies on scales such as fluid reasoning, internalization, and externalization, offering potential for personalized insights and a deeper understanding of the link between brain dynamics and behavior.

To establish a link between internal cognitive processes and observable behavior, researchers utilized Ridge Regression – a statistical technique adept at handling correlated variables – to translate the optimized parameters of the Dynamic Mean Field Model into quantifiable behavioral measures. This approach effectively created a predictive mapping, allowing the model’s internal state, as defined by its parameters, to forecast individual differences in behavioral traits. The success of this regression indicates the model doesn’t merely simulate brain activity, but captures core computational principles directly related to how behavior manifests. By demonstrating a statistically significant correlation between model parameters and behavioral scales, the study confirms the model’s capacity to move beyond simulation and offer genuine behavioral prediction, opening avenues for understanding the neural basis of individual differences.

A significant benefit of utilizing a trained Dynamic Mean Field Model lies in its capacity for cross-subject generalization – the ability to accurately predict behavioral traits in new individuals, beyond those used during the model’s initial training. This predictive power transcends individual variability, suggesting the model captures underlying, generalizable principles of cognitive function. Instead of requiring bespoke calibration for each person, the model’s parameters, honed through optimization strategies like Hierarchy-Informed Curriculum Optimization (HICO), appear to reflect broadly applicable neural mechanisms. This opens possibilities for applying the model to diverse populations and even for anticipating behavioral responses in previously unseen subjects, representing a substantial step toward a more universal understanding of the neural basis of behavior.

The study demonstrated a compelling link between optimized computational model parameters and measurable behavioral traits, with the Hierarchy-Informed Curriculum Optimization (HICO) strategy yielding the strongest predictive power. Specifically, HICO achieved the highest [latex]R^2[/latex] values when predicting scores on scales assessing fluid reasoning, internalization – the capacity to represent internal states – and externalization, reflecting behavioral expression. Importantly, this predictive capability wasn’t limited to the data used for training; HICO consistently maintained robust performance even when tested on individual data points left out of the initial training set – a process known as Leave-One-Out (LOO) validation. In contrast, alternative training strategies, namely homogeneous and flat heterogeneous approaches, failed to generalize, their predictive abilities collapsing to zero under the same LOO conditions, highlighting HICO’s superior capacity for cross-validation and reliable behavioral prediction.

![Only the Hierarchical Conditioning Optimization (HICO) strategy successfully identified solutions encoding behaviorally relevant information across measures of fluid reasoning ([latex]R^{2}[/latex]), inwardly directed symptoms ([latex]R^{2}[/latex]), and outwardly directed tendencies ([latex]R^{2}[/latex]), as demonstrated by significant [latex]R^{2}[/latex] values and permutation-based significance testing with false discovery rate correction.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11398v1/figures/fig_methods_by_target.png)

The pursuit of robust whole-brain models, as demonstrated by this research, echoes a fundamental tenet of mathematical reasoning. The study’s success in achieving cross-subject generalization through a biologically-inspired curriculum suggests a search for invariants – principles that remain true even as complexity increases. As John McCarthy observed, “Every technology has unintended consequences.” This is particularly poignant when modeling the brain; simplifying assumptions, while necessary, can obscure critical dynamics. However, by prioritizing a curriculum learning approach, the research effectively steers the optimization process, allowing the model to converge on solutions that exhibit consistent predictive power across diverse subjects – a testament to the enduring power of seeking invariant properties even in the face of vast computational landscapes. Let N approach infinity – what remains invariant?

The Road Ahead

The demonstrated efficacy of curriculum learning, guided by hierarchical biological principles, within the optimization of Dynamic Mean Field Models is not, in itself, a revelation. Rather, it is a necessary corrective. The field has long indulged in the illusion that sufficient computational power, applied indiscriminately, could circumvent the need for principled algorithmic design. This work subtly, and thankfully, refutes that notion. The gains in cross-subject generalization are not merely improvements in predictive accuracy; they are evidence that a search space informed by biological plausibility is demonstrably more efficient-and therefore, more elegant-than a purely empirical one.

However, the current approach remains computationally intensive. The asymptotic scaling of evolutionary algorithms, even when guided by a refined curriculum, presents a fundamental challenge. Future work must focus on reducing the search space a priori, perhaps through the incorporation of more stringent constraints derived from neuroanatomical data or biophysical modeling. The true test will lie in extending this methodology to models of increasing complexity – models that approach the full intricacy of the mammalian brain, rather than simplified abstractions.

Ultimately, the pursuit of whole-brain modeling is not merely an exercise in computational neuroscience. It is a quest to understand the fundamental principles of information processing-principles that may, surprisingly, reveal more about the nature of intelligence itself. The path forward demands not simply better algorithms, but a deeper commitment to mathematical rigor and a willingness to embrace the inherent limitations of our current tools.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11398.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Marshals Episode 1 Ending Explained: Why Kayce Kills [SPOILER]

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

2026-02-15 06:18