Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed an AI-powered system that streamlines the entire process of creating proteins designed to bind to specific targets, promising faster and more efficient drug discovery.

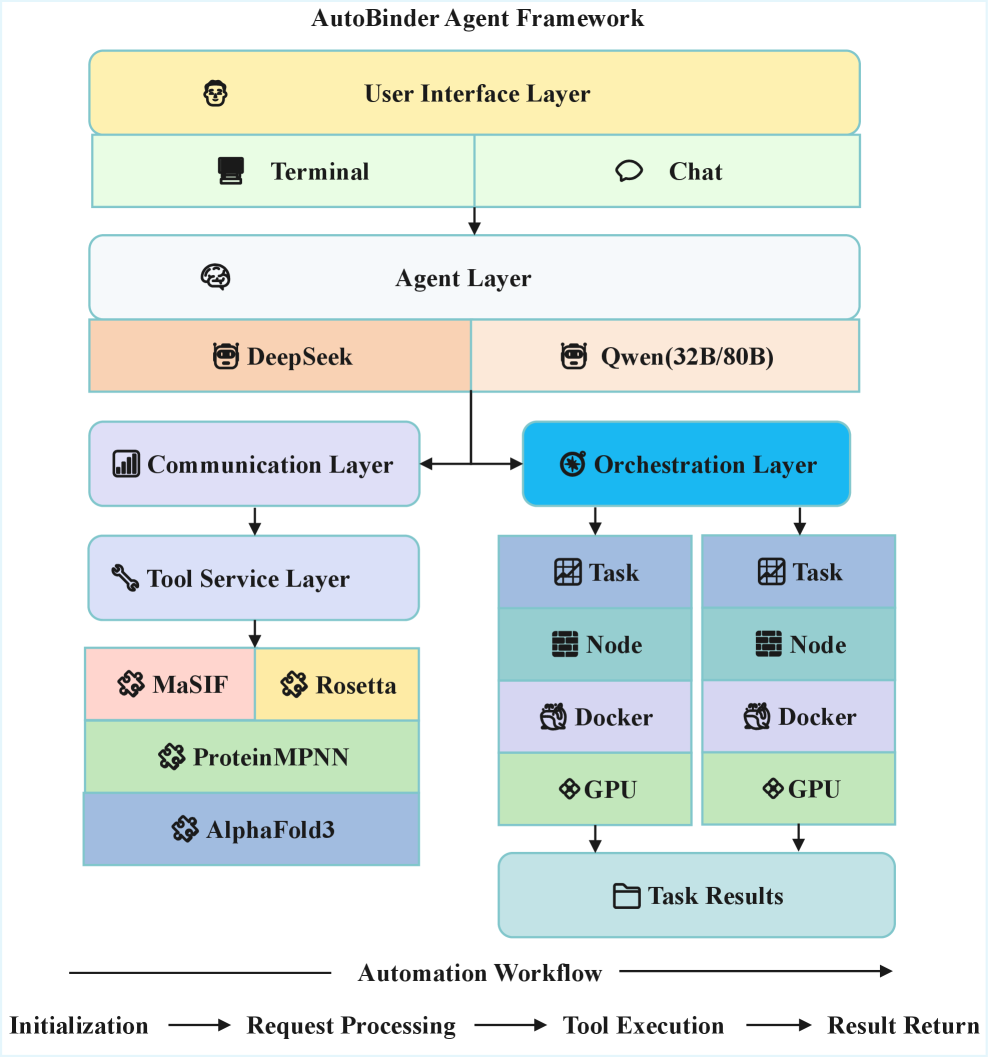

AutoBinder Agent utilizes large language models and the Model Context Protocol to integrate tools like AlphaFold3 and Rosetta for end-to-end protein binder design.

Fragmented workflows and inconsistent interfaces hinder modern AI-driven drug discovery despite advances in individual tools. To address this, we present ‘AutoBinder Agent: An MCP-Based Agent for End-to-End Protein Binder Design’, an agentic framework that integrates state-of-the-art biochemical databases and AI models-including AlphaFold3 and Rosetta-using the Model Context Protocol (MCP) and a Large Language Model. This system automates de novo protein binder generation, enhancing reproducibility and reducing manual overhead throughout the design process. Will this approach unlock a new era of rapid, AI-driven protein therapeutics discovery?

The Inevitable Complexity of Creation

Conventional protein design represents a significant undertaking, frequently necessitating cycles of experimental testing and refinement. The sheer vastness of possible amino acid sequences – the ‘sequence space’ – presents a formidable challenge; even modestly sized proteins offer an astronomical number of potential configurations. Researchers typically modify existing proteins with known structures, a process still demanding substantial effort to achieve desired alterations in function or stability. Exploring entirely new protein sequences, rather than tweaking established ones, is exponentially more difficult because predicting how a novel sequence will fold into a functional three-dimensional structure remains a major hurdle. This limitation necessitates extensive laboratory validation, where researchers synthesize and characterize numerous candidate proteins, a time-consuming and resource-intensive endeavor. Consequently, the development of proteins with entirely novel capabilities is often constrained by the practical limitations of exploring this immense sequence landscape.

Creating proteins from scratch, known as de novo design, presents a challenge significantly greater than modifying existing ones due to the immense complexity of translating genetic information into a functional three-dimensional structure. Unlike optimization tasks that refine pre-existing proteins, de novo design requires predicting how a novel amino acid sequence will spontaneously fold into a stable and biologically active conformation. This necessitates innovative computational methods – including physics-based simulations and machine learning algorithms – capable of navigating the vast “sequence space” and accurately assessing the energetic landscape of protein folding. Success hinges on overcoming the inherent unpredictability of these processes and designing sequences that reliably converge on the desired structure and function, a feat that demands substantial advancements in both computational power and theoretical understanding.

Predicting how a newly designed amino acid sequence will fold into a functional three-dimensional structure remains a significant hurdle in de novo protein design. Current computational methods, while increasingly sophisticated, often struggle with the sheer complexity of the protein folding process, leading to inaccuracies in predicted structures and, consequently, reduced stability. This unreliability stems from the difficulty in modeling the intricate interplay of forces – including electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects – that govern protein conformation. As a result, even computationally promising designs frequently fail to achieve the desired stability or exhibit the intended function when synthesized and tested, necessitating extensive experimental screening and iterative refinement to identify viable candidates. The limitations in accurately forecasting structural integrity directly impede the creation of novel proteins with tailored properties, such as enhanced catalytic activity, targeted binding affinity, or improved therapeutic potential.

Orchestrating the Inevitable: An Agentic System

The AutoBinder Agent employs a multi-layer agentic system to automate protein design from initial task definition to final output. This architecture integrates a Large Language Model (LLM) as its central control mechanism, responsible for high-level reasoning, task decomposition, and the orchestration of specialized computational tools. The LLM doesn’t directly perform the biophysical calculations; instead, it plans a sequence of operations to be executed by these tools, managing data flow and interpreting results to guide the design process. This layered approach allows for modularity and scalability, enabling the system to address complex design challenges that require the coordinated application of diverse computational methods.

The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is a critical component of the AutoBinder Agent, functioning as a standardized interface for communication between various computational tools used in protein design. MCP defines a consistent data format and communication pathway, enabling the agent to dynamically integrate and orchestrate tools such as Rosetta, AlphaFold, and PLIP without requiring tool-specific adaptation code. This standardization facilitates seamless data transfer and ensures that the output of one tool is correctly interpreted as input by the next, promoting a robust and flexible workflow. The protocol utilizes a JSON-based messaging system to encapsulate tool inputs, outputs, and associated metadata, allowing the agent to monitor execution, handle errors, and adaptively adjust the workflow as needed.

The AutoBinder Agent demonstrates autonomous protein design capabilities through integrated task understanding, tool planning, and error recovery mechanisms. This allows the agent to interpret design requests, formulate a sequence of computational steps utilizing appropriate tools, and implement corrective actions when encountering issues during execution. Performance evaluations, conducted across five standardized prompt tasks, yielded an overall success rate of 93.86%, indicating robust and reliable operation in achieving specified design goals without requiring human intervention.

Mapping Potential: From Interaction Prediction to Mini-Protein Construction

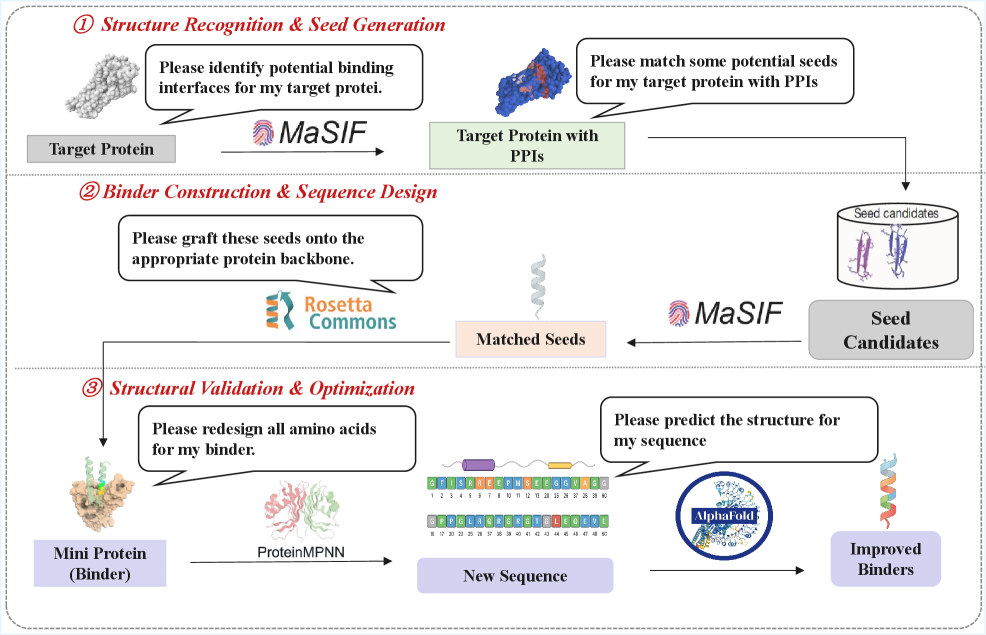

The initial step in mini-protein design involves identifying potential interaction sites on the target protein using MaSIF (Multi-Scale Interaction Field). This geometric deep learning tool analyzes the 3D structure of the target protein to predict surface regions likely to participate in intermolecular interactions. MaSIF operates by learning representations of protein geometry and using these to score the propensity of different surface patches to form stable interactions with other molecules. The output of MaSIF is a set of predicted interaction sites, which are then used to guide the selection of appropriate building blocks for mini-protein construction. These predictions are based on the tool’s ability to discern structural features indicative of interaction potential, such as surface curvature, electrostatic potential, and the presence of specific amino acid residues.

Following prediction of interaction sites on the target protein, the agent employs MaSIF to perform seed retrieval, a process of identifying structural fragment candidates suitable for mini-protein construction. This involves querying a database of known protein structures using the predicted interaction sites as constraints. MaSIF’s geometric deep learning capabilities allow it to efficiently search for fragments that exhibit complementary shapes and chemical properties to the target interaction site, prioritizing those predicted to bind with high affinity. The retrieved fragments serve as the building blocks for constructing initial mini-protein designs, which are subsequently refined and optimized.

Rosetta facilitates mini-protein construction through fragment grafting and protein modeling techniques. Specifically, the software employs a Monte Carlo approach to explore conformational space, optimizing the assembled mini-protein structure based on an energy function that considers both the sequence of the grafted fragments and the desired interaction geometry. This process involves iteratively perturbing the structure, accepting or rejecting changes based on their impact on the energy score, and ultimately generating a diverse set of candidate mini-proteins. Rosetta also incorporates features for sidechain packing and refinement, ensuring that the final models are structurally realistic and likely to adopt a stable conformation.

The Illusion of Control: Optimizing for Function and Validating the Outcome

The agent leverages ProteinMPNN, a powerful computational tool, to meticulously refine the amino acid composition of mini-proteins. This process isn’t random; rather, it’s a targeted redesign aimed at bolstering crucial characteristics like stability – ensuring the protein maintains its structure – and affinity, which dictates how strongly it binds to its target. By strategically altering the sequence, the agent optimizes these properties, effectively tailoring the mini-protein for enhanced performance in its intended function. This computational optimization represents a significant step toward designing proteins with predictable and desirable characteristics, opening doors for applications in areas like targeted drug delivery and novel biomaterial creation.

Accurate protein structure prediction is paramount to validating redesigned protein sequences, and the workflow leverages the capabilities of AlphaFold3 for this critical assessment. Following amino acid optimization via ProteinMPNN, AlphaFold3 predicts the three-dimensional structure of the modified mini-protein, enabling a robust evaluation of design quality. This prediction isn’t merely a visual confirmation; it provides quantifiable data regarding the stability and functionality of the redesigned protein, identifying potential issues with folding or active site formation. By comparing the predicted structure to the original design goals, the system can iteratively refine the sequence, ensuring that the final protein exhibits both desired characteristics and structural integrity – a process essential for translating computational design into functional biomolecules.

The agent’s proficiency is demonstrated through consistently high performance metrics across crucial operational areas. Achieving 96.4% accuracy in task understanding ensures precise interpretation of design goals, while a 94.8% success rate in both tool selection and execution order highlights its ability to autonomously navigate the complex workflow – from initially predicting protein interactions to ultimately validating the redesigned structure. This level of performance enables the agent to function with minimal human intervention, effectively managing the entire protein optimization pipeline and streamlining the process of creating novel, functional mini-proteins.

The pursuit of automated protein binder design, as demonstrated by AutoBinder Agent, feels less like construction and more like tending a garden. One cultivates conditions – the LLMs, the MCP, the integration of tools like AlphaFold3 and Rosetta – and observes what takes root. It echoes a sentiment long held: “Cogito, ergo sum.” The system doesn’t create binders so much as it provides a space where their existence becomes probable. Dependencies, of course, remain. The technologies will invariably shift, but the underlying need for iterative refinement – the constant testing and adaptation – will endure, a compromise frozen in time, perpetually reshaping the landscape of possibility.

The Looming Repair

The automation of protein binder design, as demonstrated by AutoBinder Agent, isn’t a destination, but the careful arrangement of dependencies. Every call to AlphaFold3, every Rosetta relaxation step, is a promise made to the past – a commitment to maintaining a specific computational landscape. The system will break. The question isn’t if, but where, and what unanticipated failures will emerge as the design space expands. This is not a flaw, but the nature of growth; a system attempting to outpace its own entropy.

The true challenge lies not in optimizing the current workflow, but in building the capacity for self-correction. The architecture must anticipate its own obsolescence. The future isn’t about tighter control – control is an illusion that demands SLAs – but about cultivating a resilient ecosystem capable of absorbing and adapting to inevitable change.

One can foresee a cycle: design, failure, diagnosis, automated repair, and then, eventually, a redesign of the repair mechanisms themselves. Everything built will one day start fixing itself, and the most elegant systems will be those that facilitate that process with minimal intervention. The system isn’t a tool, it’s a garden.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.00019.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Prestige Requiem Sona for Act 2 of LoL’s Demacia season

- Channing Tatum reveals shocking shoulder scar as he shares health update after undergoing surgery

- Who Is Sirius? Brawl Stars Teases The “First Star of Starr Park”

2026-02-04 05:43