Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new benchmark assesses how well autonomous agents can independently arrive at established scientific findings, revealing significant hurdles to automating the full research cycle.

FIRE-Bench provides a rigorous evaluation of large language model agents on tasks requiring scientific rediscovery, highlighting limitations in current approaches to full-cycle research.

Despite the promise of autonomous agents to accelerate scientific discovery, rigorously evaluating their capacity for verifiable insight remains a significant challenge. To address this, we introduce FIRE-Bench: Evaluating Agents on the Rediscovery of Scientific Insights, a benchmark that assesses agents’ ability to independently rediscover established findings from recent machine learning research. Our results demonstrate that even state-of-the-art agents struggle with full-cycle research, achieving limited rediscovery success and exhibiting consistent failure modes in experimental design and evidence-based reasoning. Can we develop more robust evaluation frameworks and agent capabilities to unlock the full potential of AI-driven scientific exploration?

The Illusion of Progress: Data Volume vs. True Insight

The established foundations of scientific advancement, characterized by meticulous experimentation and peer review, are increasingly challenged by the sheer volume and complexity of modern data. While undeniably robust, these traditional methods often require substantial time and resources, creating bottlenecks in fields like materials science and drug discovery. A single research cycle-from formulating a hypothesis to validating findings-can span years, limiting the pace of innovation and hindering the ability to address rapidly evolving challenges. This inherent slowness isn’t a flaw in the process itself, but rather a consequence of its manual nature; researchers are limited by the speed at which they can design, execute, and analyze experiments, and the escalating costs associated with maintaining complex laboratory infrastructure and large research teams are becoming unsustainable. Consequently, there is growing impetus to explore automated approaches that can accelerate discovery and unlock new frontiers of knowledge.

Modern scientific research is increasingly characterized by datasets of immense scale and intricate relationships, pushing the boundaries of human cognitive capacity. This complexity necessitates the development of automated systems capable of independently managing the entire research process – a complete lifecycle of inquiry. These systems must not only analyze existing data, but also formulate novel hypotheses, design and execute experiments – whether simulations or physical tests – and ultimately, interpret results to draw meaningful conclusions. The ambition is to move beyond tools that simply accelerate specific tasks, towards artificial intelligence capable of genuine scientific exploration, identifying previously unknown patterns and driving innovation across diverse fields. Such a shift requires integrating capabilities ranging from machine learning and knowledge representation to automated reasoning and experimental design, effectively creating a self-directed scientific investigator.

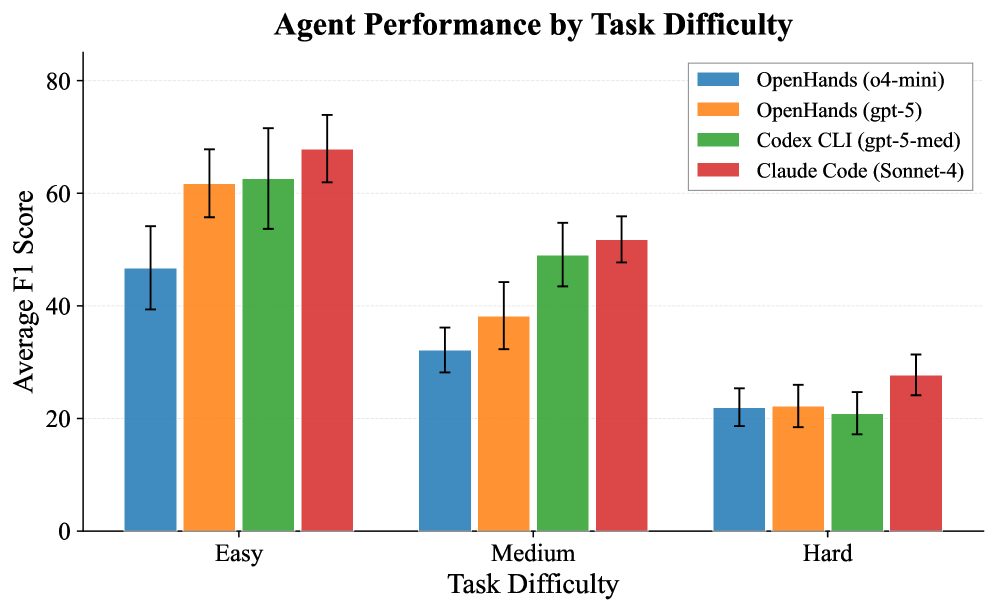

Despite advances in artificial intelligence, current systems struggle with the comprehensive reasoning required for genuine scientific discovery. While adept at performing specific, narrowly defined tasks – such as predicting protein structures or identifying correlations in datasets – these AI models often fail when confronted with the broader context and iterative nature of scientific inquiry. This limitation is demonstrably reflected in benchmarks like FIRE-Bench, where even state-of-the-art AI achieves F1 scores below 50%, highlighting a significant gap between task-specific performance and the holistic reasoning needed to formulate hypotheses, design experiments, and draw meaningful conclusions – effectively indicating that current AI struggles to think like a scientist and often misses crucial connections or fails to adequately validate its findings.

FIRE-Bench: A Rigorous Test, or Just a More Complicated Loop?

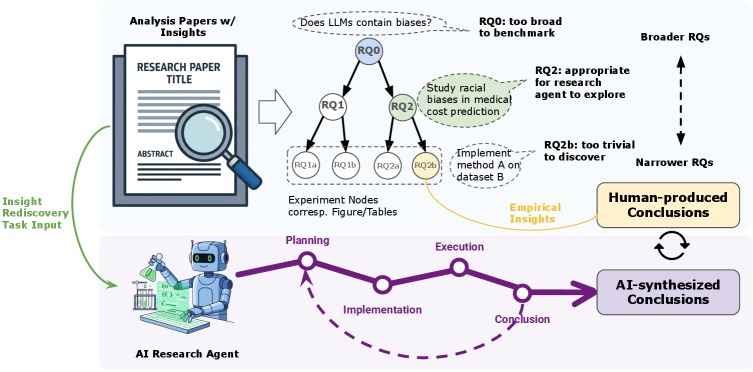

FIRE-Bench introduces a novel evaluation paradigm shifting focus from task completion to the emulation of the complete empirical research cycle. This framework necessitates agents to perform iterative stages including hypothesis generation, experimental design, data collection, analysis, and conclusion formation – mirroring the scientific method. Unlike benchmarks evaluating isolated skills or final outputs, FIRE-Bench assesses an agent’s capacity to autonomously navigate the entire research process, providing a more holistic measure of scientific reasoning and problem-solving ability. The benchmark is designed to evaluate not just if an agent can arrive at a correct answer, but how it arrives at that answer, emphasizing the importance of methodological rigor and reproducibility.

Traditional benchmarks in AI often evaluate agents on discrete tasks or their capacity to produce finished research papers, a methodology termed ‘Automated Paper Generation’. FIRE-Bench diverges from this approach by specifically assessing an agent’s ability to independently perform the complete cycle of empirical research – formulating hypotheses, designing experiments, analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This focus on ‘Rediscovery’ emphasizes the process of scientific inquiry rather than solely the final output, allowing for granular evaluation of each research stage and identifying weaknesses in an agent’s reasoning or experimental design capabilities. This paradigm shift enables a more nuanced understanding of an agent’s scientific aptitude beyond simple result replication.

FIRE-Bench employs a ‘Research Problem Tree’ to decompose complex research questions into discrete, evaluable stages, including problem formulation, hypothesis generation, experimental design, data analysis, and conclusion. Performance is assessed at each of these stages, allowing for granular identification of agent strengths and weaknesses throughout the research lifecycle. Current evaluations utilizing state-of-the-art agents demonstrate limited capabilities, yielding an average F1 score of below 50% across the entire Research Problem Tree, indicating substantial room for improvement in automated research methodologies.

Dissecting the Errors: Where Do These ‘Intelligent’ Systems Fail?

Claim-Level Evaluation, the core assessment method within FIRE-Bench, operates by dissecting agent-generated outputs into individual, verifiable claims. These claims are then systematically compared against a pre-defined set of established results – encompassing both factual correctness and logical consistency. This granular approach allows for precise identification of valid and invalid statements, moving beyond holistic scoring to pinpoint specific areas of strength and weakness in the agent’s reasoning process. The methodology facilitates a nuanced understanding of an agent’s capabilities, enabling targeted improvements and a detailed analysis of its performance on complex tasks requiring evidence-based conclusions.

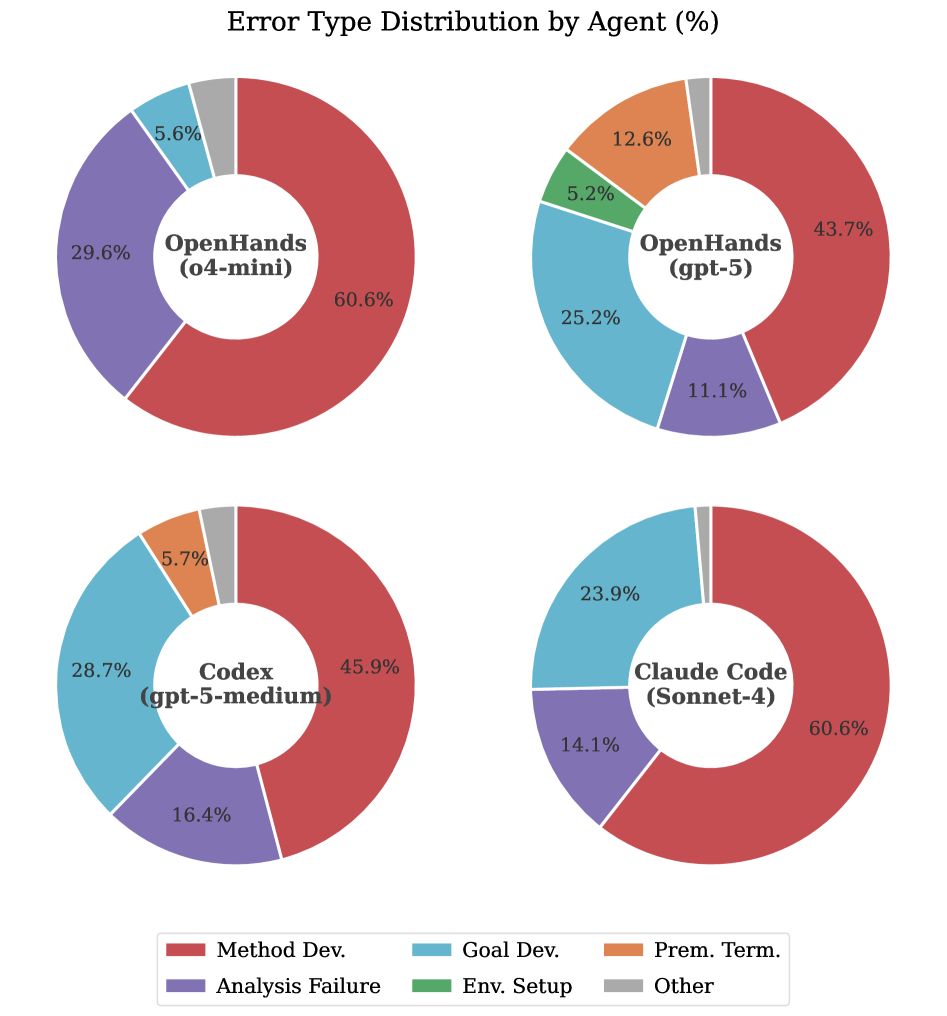

The FIRE-Bench Error Analysis Framework systematically identifies the root cause of inaccuracies in agent-generated research findings. This framework categorizes errors based on their origin – deficiencies in research planning, such as inadequate hypothesis formulation or insufficient data source selection; issues during implementation, encompassing errors in data acquisition, analysis techniques, or code execution; and failures in conclusion formation, where the agent misinterprets results or draws unsubstantiated inferences. By classifying errors into these distinct categories, the framework facilitates targeted improvements to agent capabilities and research methodologies, ultimately enhancing the reliability and validity of generated findings.

Evaluation of research agents within FIRE-Bench utilizes both open-source and proprietary Large Language Models (LLMs), including OpenHands, Codex, and Claude Code. The claim extraction component of the evaluation pipeline demonstrates high performance, achieving a precision of 0.95, indicating a low rate of false positives in identifying research claims. Recall is measured at 0.86, signifying the system’s ability to identify a substantial proportion of all valid claims. The overall F1 score, a harmonic mean of precision and recall, is 0.89, representing a balanced performance across both metrics and validating the reliability of the claim extraction process as a foundational component of the evaluation framework.

The Limits of Automation: Cost, Contamination, and the Illusion of Discovery

The practical application of large language models (LLMs) to complex research endeavors is significantly constrained by substantial API costs. Each query to these models-necessary for tasks like data analysis, hypothesis generation, and literature review-incurs a financial burden that quickly escalates with project scope and duration. This economic barrier limits accessibility, particularly for researchers with limited funding or those in resource-constrained institutions. Furthermore, the cost structure hinders scalability; replicating experiments or extending research to larger datasets becomes prohibitively expensive, effectively creating a bottleneck in the pursuit of scientific discovery. The current reliance on commercially-provided LLM APIs, therefore, necessitates exploration of cost-effective alternatives, such as open-source models or optimized prompting strategies, to broaden participation and accelerate progress in computationally-intensive fields.

A significant challenge in evaluating the true intelligence of large language model agents lies in differentiating genuine discovery from simple memorization of training data – a phenomenon known as data contamination. Current agents, when presented with research tasks, may appear to ‘solve’ problems not through novel reasoning, but by recalling facts directly present within their extensive training datasets. This poses a critical issue for assessing their capacity for true scientific inquiry, as the ability to generalize to unseen information and formulate original hypotheses is paramount. Detecting this contamination requires carefully designed benchmarks that explicitly test for knowledge beyond the training corpus, ensuring that reported successes reflect genuine understanding and not merely regurgitation of previously learned material. Ultimately, addressing data contamination is vital for building trustworthy AI systems capable of contributing meaningfully to scientific advancement.

FIRE-Bench represents a departure from conventional benchmarks that prioritize reproducing known facts; instead, it assesses an agent’s capacity for genuine discovery within a scientific context. This innovative design poses a significantly greater challenge, requiring agents to formulate hypotheses, design experiments, and interpret results – skills crucial for advancing research but not typically evaluated in standard reproducibility tests. Current language model agents, when subjected to FIRE-Bench’s rigorous demands, achieve F1 scores below 50%, indicating a substantial gap between their ability to recall information and their capacity for independent scientific reasoning. This performance suggests that while these agents excel at accessing and synthesizing existing knowledge, they struggle with the creative problem-solving inherent in true discovery, highlighting a key area for future development in artificial intelligence.

The pursuit of fully autonomous research, as detailed in this paper’s introduction of FIRE-Bench, feels predictably optimistic. It’s a charming notion, agents rediscovering established scientific insights, but the limitations revealed – the struggle with full-cycle research automation – aren’t surprising. As Brian Kernighan aptly stated, “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” This rings true; elegant architectures for autonomous discovery quickly reveal unforeseen complexities when confronted with the messiness of real-world data and the inherent ambiguities within existing scientific literature. FIRE-Bench isn’t exposing a failure of the idea of autonomous research, simply confirming that the implementation will inevitably wrestle with unforeseen edge cases and require constant refinement – a cycle that never truly ends.

What Comes Next?

FIRE-Bench, and benchmarks like it, will inevitably accrue a patina of obsolescence. The questions it poses – can an agent rediscover known science? – are less interesting than the ways in which agents will find novel, and likely undocumented, edge cases. Tests are, after all, a form of faith, not certainty. The benchmark will be gamed, then surpassed, then rendered irrelevant by improvements in model scale or architectural trickery. This is not a criticism, merely an observation of entropy.

The more persistent challenge lies not in achieving rediscovery, but in the automation of error. Current systems excel at echoing established knowledge; they will predictably fail in the messy, unpredictable work of identifying flawed premises or unreplicable results. A truly autonomous scientific agent will need to be as adept at dismantling bad science as it is at confirming the good, a capability that demands more than just clever prompting or reinforcement learning.

Future work should focus less on achieving ‘full-cycle research’ and more on quantifying the cost of automation. Every automated process introduces new points of failure. The metric isn’t simply ‘did it rediscover X?’ but ‘how many regressions were introduced in the process, and at what operational expense?’ The ideal system isn’t one that never fails, but one that fails gracefully, and cheaply.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02905.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Prestige Requiem Sona for Act 2 of LoL’s Demacia season

- Channing Tatum reveals shocking shoulder scar as he shares health update after undergoing surgery

- Who Is Sirius? Brawl Stars Teases The “First Star of Starr Park”

2026-02-04 10:50