As a seasoned writer and observer of Hollywood’s ever-shifting landscape, I can’t help but empathize with Kaplan’s plight. His story is a testament to the rollercoaster ride that is life in Tinseltown, where dreams are as elusive as the next big break.

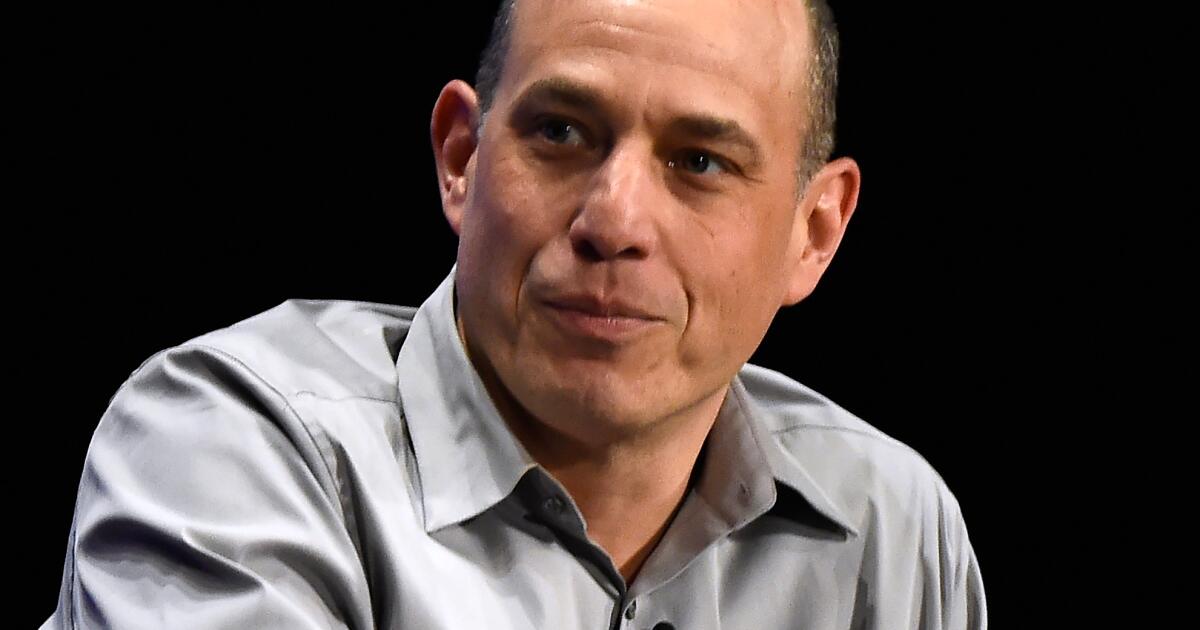

Bruce Eric Kaplan started a journal mid-pandemic, hoping to make sense of a world jolted by the vapor trails of Donald Trump’s presidency and COVID-19. The external chaos was leaking into his personal life, manifesting itself into a series of indignities that did little to quell his anxiety about a country turned upside down. The longtime cartoonist for the New Yorker and TV writer-producer was also engaged in another kind of madness: trying to set up his own passion project, a small-screen show about a May-December romance.

In the opening of his journal, the accomplished actor, known for series like “Girls,” “Six Feet Under” and “Seinfeld,” expresses a desire to encounter a deeply meaningful or significant experience.

Spoiler alert: It doesn’t happen.

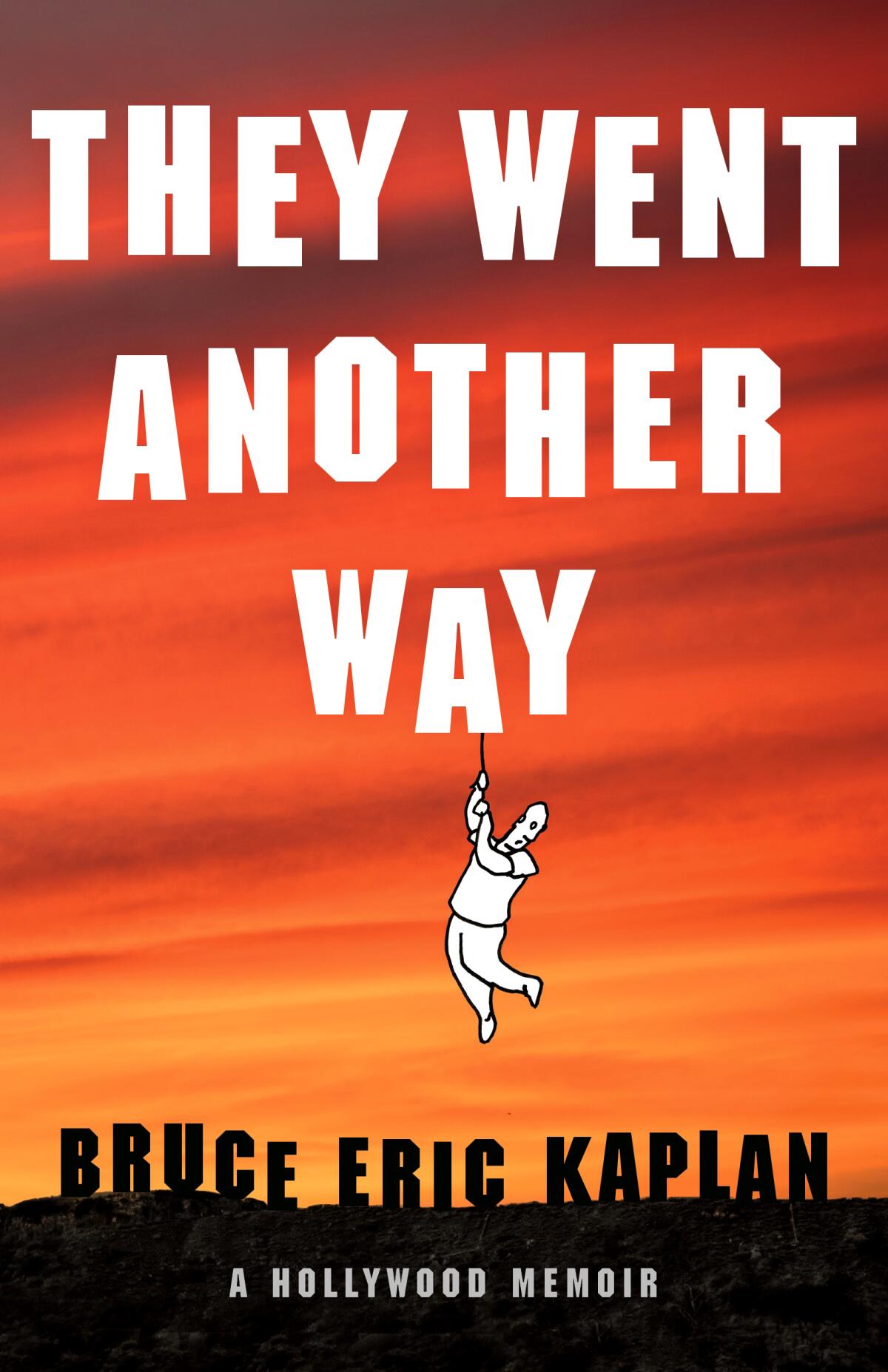

Instead of starting as a diary in early 2022, Kaplan later transformed it into a book titled “They Went Another Way.” This book offers a humorous, wistful, and heartfelt account of Kaplan’s unique experience during their personal ‘plague year.’

Speaking over a cup of coffee and a bagel at the Clark Street Diner in Hollywood, he admits that he began this journal as an outlet to prevent himself from becoming overwhelmed. Following the completion of his book, he discovered Elizabeth Gilbert’s ‘Big Magic,’ which essentially encourages readers to pay attention to the world around them and record whatever they feel compelled to write. This was his approach to writing.

Kaplan found himself at odds with the messages he was receiving from the world: Although dedicated to television writing, he grappled with growing skepticism about producing substantial work within Hollywood’s realm. By then, this seasoned TV writer had been jobless for over half a year, and the impending tuition fees for his children’s private school hung heavy upon him like Damocles’ sword.

Although existential despair doesn’t provide financial support, he perseveres with his endeavor. Early diary entries by Kaplan reflect optimism: His representatives pass on his pilot script to Glenn Close, whose agents confirm she has read it and is interested in acting in it. In a time of uncertainty, Kaplan discovers a ray of hope: an A-list actor expressing interest in producing his series.

However, Hollywood is often a destination where dreams frequently meet their demise, and “They Went Another Way” serves as a humorous guide to how promising concepts can be gradually suffocated by a clumsy and inefficient system ruled by streamocracy – a term that refers to the power held by those who control the flow of information. This system’s native language is the skillfully vague untruth.

As a movie reviewer, I found myself initially intrigued by the unfolding tale of screenwriter Kaplan and director Max Barbakow, who were about to embark on an exciting journey together. The spark ignited during their Zoom meeting, where Kaplan’s script caught Barbakow’s eye, and they began brainstorming potential collaborators and filming locations for their upcoming project.

Kaplan embarks on a frantic quest for stability, as the TV scriptwriter attempts to seal the cracks in his tumultuous life, which he candidly describes in an often embarrassing manner in his book. Reflecting on that time, Kaplan shares, “I was at a turning point then. My family and I were contemplating a move to New York with our children amidst all the chaos. I felt compelled to write about the real experiences I was having.

Time quickly passes, and the initial warmth from Kaplan’s project begins to dissipate. Before long, he finds himself in a situation that many face when working in Hollywood: “I’m still awaiting confirmation if Max Barbakow will direct the Glenn Close script,” Kaplan writes. “I’m also waiting for a meeting with Will Forte regarding my New Zealand project. Additionally, I’m waiting on several other matters I don’t feel like detailing here.

Kaplan is drawn into a vortex of elongated time, where a day turns into a week turns into a month and where deadlines are written on water. Close emails Kaplan about contacting Pete Davidson as her co-star; per Kaplan, she has “great chemistry with” the “Saturday Night Live” alum, a friend of hers. Close texts a copy of the script to Davidson, who reads the first 11 pages and wants to do it, which, Kaplan writes, “is quite something, since his character doesn’t even show up until pages after that.”

The procedure of gathering everyone on a Zoom meeting becomes unnecessarily intricate and reminiscent of Kafka. Davidson frequently feigns illness, but it’s discovered that he is actually traveling abroad with his girlfriend Kim Kardashian, or something similar. As it appears as though things might be going Kaplan’s way, there is a call for more – more narrative, more plot, more writing without compensation. Hope consistently collides with the rocks of disillusionment. Initially, Showtime expresses interest in Kaplan’s show, but then Netflix seems to take priority. However, both parties eventually back out.

Kaplan feels drained from constantly moving forward only to take a step back. He copes with his anxiety by meditating, working out, and compulsively cleaning his home. The process of completing his daughter’s private school application is almost overwhelming for him, and he and his wife get hurt by errant soccer balls during separate incidents at their daughter’s practice. Kaplan contemplates switching careers, as he expresses in a note: “My plan B is…to deliver turkey sandwiches in New Zealand. I will arrange to have some turkeys transported there and start a turkey farm…if my current script doesn’t get sold, then I am definitely considering becoming a turkey farmer in New Zealand.

There is no such thing as a sure thing, but the streaming cosmos has given that truism a power boost; there are so many potential projects spread across so many creators that it seems as if no one can commit to anything, let alone focus on any one thing, for very long, which has been made even worse by the severe retrenchment among Hollywood studios to greenlight any new projects. Risk aversion has become an end in itself. Kaplan, who began his career in the four network era, has seen the changes firsthand.

Kaplan stated that when there were only four networks, his agent would arrange pitches for us, and we’d have a meeting within two days after the initial call. Within this timeframe, we’d learn whether they were interested in our idea or not. The executives would focus on the concept and characters. They didn’t ask about the ending of the first season or require outlining the second season at that point.

When Kaplan reluctantly accepts to pen a second script for a possible client, things don’t turn out favorably. The script is flatly declined by Close, who informs Kaplan, “If I don’t find it engaging, then I assume nobody else will either.” This leads Kaplan to ponder in his diary whether “assuming that everyone would share your feelings is a characteristic of extreme narcissism.

Time moves on, and everything eventually fades away, including Kaplan’s various projects. By the end of the year, Kaplan finds himself in the same position as at the beginning, but not without experiencing a whirlwind of Zoom meetings, emails, and messages that drain him. Despite feeling exhausted, he forces himself to start fresh. It’s his usual way of coping.

“This is my reality.” he says, “and I’m just trying to make the best of it.”

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- FC Mobile 26: EA opens voting for its official Team of the Year (TOTY)

2024-10-22 13:33