Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework blends the strengths of mechanistic modeling and machine learning to achieve more accurate and interpretable predictions for complex systems.

![Across the SIR, CR, and gases datasets, the average magnitude of forecasting error-measured as Mean Absolute Error [latex] MAE [/latex]-varied predictably with increasing noise levels, indicating a consistent sensitivity to data quality regardless of the specific time series being analyzed.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.04114v1/test_Avg_MAE_per_noise_gases.png)

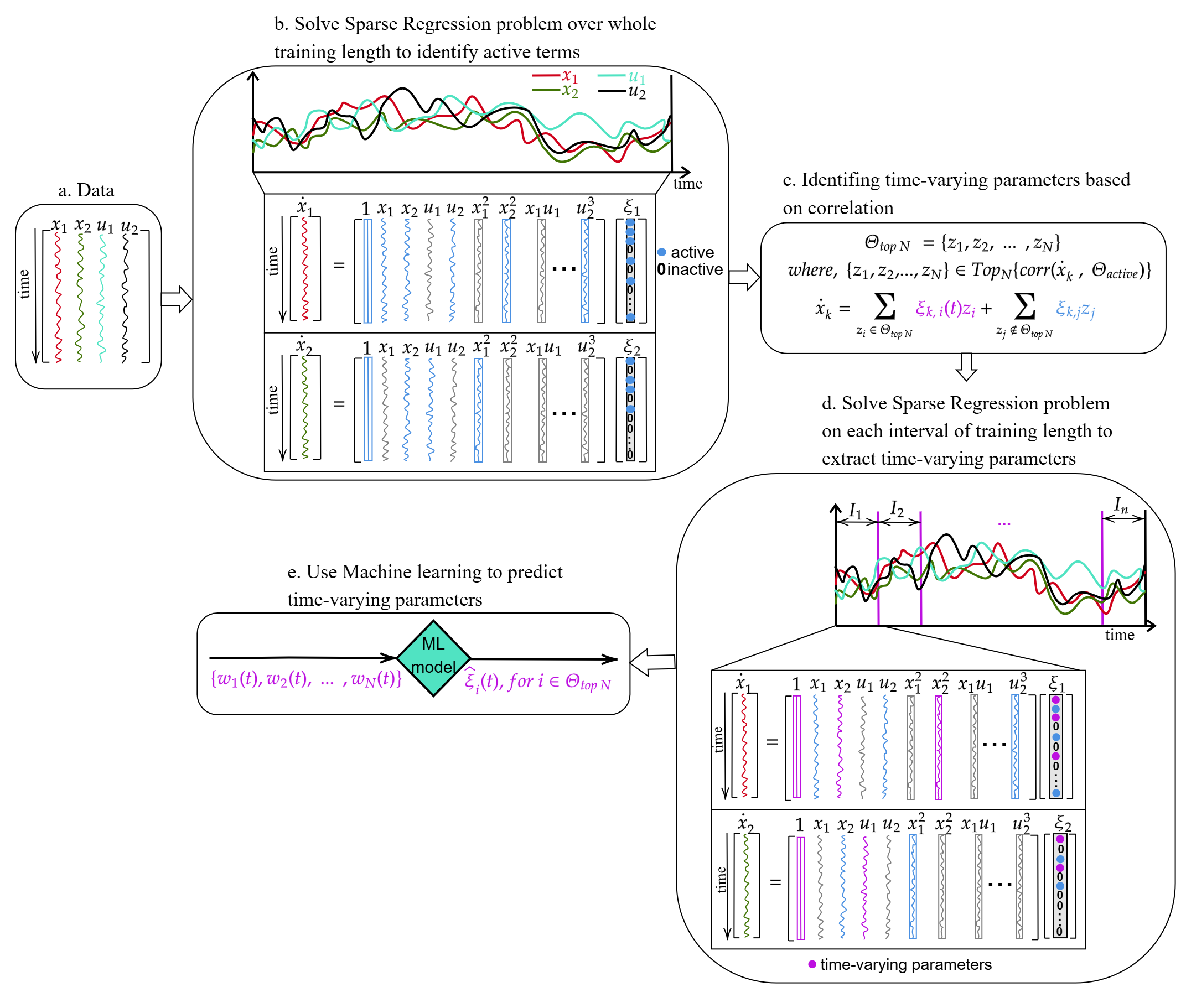

Combining sparse identification of nonlinear dynamics with machine-learned time-varying parameters enables improved forecasting and quantifiable finite-horizon error bounds.

Identifying the equations governing complex dynamical systems remains challenging, particularly when underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. This limitation motivates the research presented in ‘Turning mechanistic models into forecasters by using machine learning’, which introduces a novel framework for data-driven discovery that incorporates time-varying parameters learned through machine learning. By dynamically adapting to temporal shifts, this approach improves both the accuracy of model identification and forecasting performance-achieving errors below 6% for month-ahead predictions across multiple datasets. Could this integration of sparse equation discovery with learned parameter evolution unlock more interpretable and accurate forecasting capabilities for a wider range of complex systems?

Beyond the Black Box: Why We Need to Know How Things Work

Many ecological and environmental models historically function as “black boxes,” identifying correlations between variables without elucidating why those relationships exist. These empirical models, built on observed patterns, can accurately forecast outcomes within the specific conditions used to create them. However, their predictive capacity diminishes rapidly when confronted with scenarios outside of that limited scope-such as those arising from climate change or unforeseen disturbances. Because these models lack an understanding of the fundamental biological, chemical, and physical processes driving ecological phenomena, they struggle to extrapolate beyond the familiar, offering limited insight into how ecosystems will respond to genuinely novel conditions. This reliance on observation, while valuable, often obscures the mechanistic underpinnings necessary for truly robust and reliable predictions about the future.

The reliance on purely empirical relationships within ecological forecasting creates significant vulnerabilities when confronted with unprecedented scenarios. Traditional models, built on observed correlations, struggle to extrapolate beyond the conditions under which they were established; a system behaving predictably within a historical range may exhibit entirely novel responses when faced with climate shifts, invasive species, or pollution levels exceeding previous experience. This limitation arises because these models lack an understanding of the fundamental processes driving ecological responses, effectively treating ecosystems as ‘black boxes’-capable of outputting results, but opaque in their internal workings. Consequently, predictions become less reliable as environmental change accelerates, and the potential for unexpected and potentially catastrophic outcomes increases, highlighting the urgent need for models grounded in mechanistic understanding.

The pursuit of ecological forecasting demands a transition from purely empirical models to those grounded in mechanistic understanding, fueled by the increasing availability of comprehensive datasets. Traditional approaches, while capable of capturing existing patterns, often falter when confronted with unprecedented environmental shifts because they lack the ability to extrapolate beyond observed conditions. Data-driven mechanistic modeling integrates statistical rigor with biological and physical principles, allowing researchers to simulate complex interactions and predict system responses with greater confidence. This approach doesn’t simply identify correlations; it seeks to define the causal relationships that govern ecological processes, enabling more robust and reliable predictions of how ecosystems will behave under both familiar and novel circumstances, and ultimately informing more effective conservation and management strategies.

Reconstructing Reality: How We’re Moving Beyond Guesswork

Data-Driven Discovery circumvents the limitations of traditional system identification, which relies heavily on pre-specified model structures and assumptions about the underlying physics. Instead of imposing a functional form – such as a linear differential equation – this approach utilizes algorithms to directly regress governing equations from observed data. This is achieved by treating model terms – including nonlinear functions and derivatives – as unknowns to be estimated. By employing techniques like sparse regression, the method identifies the simplest model – in terms of the number of terms – that accurately describes the observed data. This allows for the discovery of potentially unknown or previously unconsidered relationships and provides a means of reconstructing system dynamics without a priori knowledge of the governing equations. The process typically involves collecting time-series data of relevant variables, formulating a library of candidate terms – including polynomials, trigonometric functions, and derivatives – and then using regression techniques to identify the terms that best explain the observed data, resulting in a model of the form [latex]\dot{x} = f(x, u)[/latex], where [latex]x[/latex] is the state vector, [latex]u[/latex] is the input vector, and [latex]f[/latex] is the identified governing function.

Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) operates by leveraging machine learning techniques to discover governing equations from observed data without requiring prior knowledge of the underlying system. The method functions by representing the time derivative of a state variable as a sparse linear combination of candidate functions, including polynomial terms, trigonometric functions, and user-defined terms. A regression algorithm, often employing techniques like LASSO regression, is then used to identify the fewest number of these functions that accurately describe the system’s dynamics. This sparsity is crucial, as it reveals the dominant interactions and simplifies the resulting model, effectively isolating key mechanisms from noise and irrelevant complexity. The identified equations can then be used for prediction, control, and further analysis of the system’s behavior. [latex] \dot{x} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} c_i f_i(x) [/latex], where [latex] \dot{x} [/latex] is the time derivative of the state vector, [latex] c_i [/latex] are coefficients, and [latex] f_i(x) [/latex] are the identified functions.

Traditional modeling techniques often rely on pre-defined equations or structures hypothesized by the researcher, potentially introducing bias or overlooking critical dynamics. In contrast, methods leveraging observed causal relationships prioritize the identification of governing equations directly from data, establishing a model’s structure based on empirically determined interactions. This is achieved through techniques such as identifying statistically significant relationships between variables, and then constructing a model that accurately reproduces observed system behavior. By prioritizing data-driven causal inference, these approaches aim to create models that are less susceptible to researcher bias and more capable of capturing the true underlying mechanisms of a system, even in cases where those mechanisms are not intuitively obvious.

Testing the Limits: How We Know These Models Actually Work

Expanding-window cross-validation is a technique used to assess the predictive skill of a model by iteratively training on a growing window of historical data and testing on a fixed-size subsequent period. This method begins with a small initial training set and progressively incorporates more data with each iteration, while the test set remains constant in terms of its temporal distance from the training window. By evaluating performance across multiple expanding windows, the technique provides a more realistic assessment of how the model generalizes to unseen future data compared to traditional k-fold cross-validation, particularly in time series applications where data dependencies and non-stationarity are prevalent. This approach mitigates the risk of optimistically biased performance estimates that can occur when using static training/test splits and allows for monitoring of model stability and potential performance degradation over time.

Regularization techniques address the problem of overfitting, which occurs when a model learns the training data too well, capturing noise and failing to generalize to new, unseen data. Methods such as L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization introduce a penalty term to the loss function, discouraging excessively large parameter values. This penalty is proportional to the sum of the absolute values (L1) or the sum of the squares (L2) of the model’s coefficients. By constraining the model’s complexity, regularization reduces variance and improves its ability to predict accurately on data outside of the training set, ultimately leading to more robust and reliable forecasts. The strength of the regularization is controlled by a hyperparameter, typically denoted as λ, which is tuned using techniques like cross-validation to find the optimal balance between model fit and generalization performance.

Finite-Horizon Forecast Error Bounds provide a quantifiable range within which future predictions are expected to fall, enabling more informed decision-making under uncertainty. These bounds are calculated based on the estimated variance of the model’s parameters and the length of the forecast horizon; longer horizons inherently produce wider bounds due to accumulated uncertainty. Specifically, the calculation incorporates the covariance matrix of the time-varying parameters, providing a measure of the potential error associated with each forecast. Presenting predictions alongside these bounds allows stakeholders to assess the risk associated with different scenarios and adjust strategies accordingly, rather than relying on point forecasts which offer no indication of potential error. The bounds are not confidence intervals, but rather represent a guaranteed upper limit on the forecast error with a specified probability, typically determined by the model’s assumptions and data distribution.

Evaluation of the proposed framework, specifically when applied to the Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model, indicates a measurable improvement in forecasting accuracy. Comparative analysis against implementations utilizing fixed parameters demonstrates a reduction in Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of up to 8%. This performance gain is attributed to the framework’s capacity to adapt to evolving epidemiological dynamics by estimating time-varying parameters, thereby providing a more accurate representation of disease transmission over the forecast horizon. The observed reduction in MAE suggests improved predictive capability and potentially more reliable insights for public health interventions.

Beyond Prediction: The Wider Implications and Future Directions

The developed framework extends beyond simple forecasting, offering a versatile tool for dissecting the behavior of complex, interconnected systems. Specifically, its application to Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) models-commonly used to simulate the spread of disease-allows for a more nuanced understanding of epidemiological dynamics and potentially improved public health interventions. Simultaneously, the methodology proves valuable in Consumer-Resource Models, which are central to ecological studies and resource management; by accurately predicting population fluctuations and resource consumption, it facilitates sustainable strategies for preserving biodiversity and optimizing yields. This adaptability highlights the broad potential of the approach, moving it from a purely predictive technique to a powerful instrument for systems-level analysis and informed decision-making across diverse scientific disciplines.

The predictive power of these modeling frameworks is significantly amplified through the integration of machine learning techniques, particularly algorithms like Random Forest, when addressing the complexities of time-varying parameters. Traditional models often struggle to accurately capture dynamics influenced by shifting conditions; however, Random Forest excels at identifying and incorporating these fluctuations. By analyzing historical data, the algorithm learns to recognize patterns and relationships between parameters that change over time, allowing for more nuanced and accurate predictions. This approach doesn’t require explicit definition of how parameters evolve, instead allowing the machine learning model to infer these relationships directly from the data, a capability proven effective in improving forecasts for systems ranging from epidemiological models to complex resource dynamics and even greenhouse gas fluctuations.

The developed framework extends beyond traditional epidemiological and economic modeling to offer a novel approach to understanding critical environmental processes. Investigations into Greenhouse Gas Dynamics, specifically methane ([latex]CH_4[/latex]) production and consumption, reveal intricate feedback loops previously obscured by conventional analyses, potentially leading to more accurate climate predictions. Simultaneously, applying this methodology to Cyanobacteria Dynamics – the study of blue-green algae – provides deeper insight into their role in aquatic ecosystems and the factors governing harmful algal blooms. This expansion demonstrates the versatility of the framework, allowing researchers to explore complex interactions within diverse systems and improve predictive capabilities across environmental science, ultimately informing strategies for mitigation and sustainable resource management.

Evaluations demonstrate the practical efficacy of this forecasting framework across diverse dynamic systems. Specifically, implementation within a Susceptible-Infected-Recovered (SIR) model yielded a 2.5% reduction in Mean Absolute Error (MAE) when predicting the infected population. This improvement extends to other systems as well; a 1.3% decrease in MAE was observed for the consumer population within a Consumer-Resource model, and a significant 5.7% reduction was achieved when forecasting atmospheric methane [latex]CH_4[/latex] concentrations. These results collectively suggest the framework’s robustness and potential for enhancing predictive accuracy in a range of scientific domains, offering valuable tools for understanding and managing complex, time-evolving phenomena.

The pursuit of increasingly complex models feels a bit like chasing a mirage. This research, attempting to marry mechanistic modeling with machine learning for improved forecasting, only reinforces that suspicion. It’s a pragmatic approach, acknowledging the limitations of purely theoretical systems and the inevitable drift of real-world parameters. As Alan Turing observed, “We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done.” The framework’s focus on sparse identification and finite-horizon forecast error bounds isn’t about achieving perfect prediction – it’s about building something demonstrably less wrong, and understanding the limits of that accuracy before production inevitably reveals them. Better a bounded error than an unbounded ambition.

So, What Breaks Next?

This attempt to coax forecastability from mechanistic models, by draping them in machine learning’s latest fashions, feels…familiar. The promise of sparse identification, of teasing out true dynamics from noise, is eternally appealing. Yet, the inevitable march of production data will undoubtedly reveal previously unseen parameter interactions, edge cases the algorithms haven’t considered, and a general tendency for real-world systems to defy elegant mathematical description. One suspects the finite-horizon forecast error bounds will prove optimistic, at least when applied to anything beyond a carefully curated dataset.

The true challenge isn’t building a better algorithm; it’s building one that degrades gracefully. Future work will likely focus on incorporating uncertainty quantification, not as a theoretical exercise, but as a practical necessity. Expect to see increasingly complex hybrid models, layering machine learning atop mechanistic foundations, each attempting to compensate for the other’s weaknesses. The irony, of course, is that these layers will simply add new dimensions for failure.

Ultimately, this research – like so much before it – is another iteration on a very old problem. It’s a clever approach, certainly. But everything new is just the old thing with worse docs, and a longer list of dependencies to break when the inevitable happens.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04114.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Show Time Worldwide Selection Contract: Best player to choose and Tier List

- Free Fire Beat Carnival event goes live with DJ Alok collab, rewards, themed battlefield changes, and more

- Brent Oil Forecast

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Overwatch Domina counters

2026-02-05 19:13