Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a system that uses artificial intelligence to automatically build and verify numerical solvers for complex scientific problems described in plain language.

AutoNumerics, a PDE-agnostic multi-agent pipeline leveraging large language models, achieves competitive accuracy and transparency in solving partial differential equations.

Designing accurate numerical solvers for partial differential equations (PDEs) typically demands substantial mathematical expertise, yet recent data-driven approaches often sacrifice transparency and computational efficiency. This work introduces AutoNumerics: An Autonomous, PDE-Agnostic Multi-Agent Pipeline for Scientific Computing, a novel framework that autonomously constructs transparent and accurate numerical solvers from natural language descriptions of general PDEs. By leveraging a multi-agent system and a residual-based self-verification mechanism, AutoNumerics achieves competitive or superior accuracy compared to existing methods, while also correctly selecting numerical schemes based on PDE structural properties. Could this represent a viable paradigm shift towards accessible, automated PDE solving for a wider range of scientific and engineering applications?

The Entropic Barrier to Scientific Modeling

Successfully tackling partial differential equations (PDEs) has long relied on specialized knowledge, presenting a considerable obstacle to researchers lacking extensive training in numerical methods and computational programming. Developing effective PDE solvers isn’t simply about applying a formula; it demands a deep understanding of discretization techniques – like finite element or finite difference methods – and the intricacies of code implementation to ensure accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency. This requirement for highly specialized skills limits broader participation in scientific modeling and simulation, as many researchers are forced to dedicate substantial time and resources to solver development rather than focusing on the scientific problem itself. Consequently, progress in fields reliant on PDE modeling – encompassing areas from fluid dynamics and heat transfer to electromagnetism and materials science – can be slowed by this existing barrier to entry, hindering innovation and discovery.

A significant impediment to progress in computational science lies in the persistent need for manual intervention in solving partial differential equations (PDEs). Current methodologies frequently demand substantial user expertise to meticulously adjust solver parameters and adapt algorithms for each novel problem encountered. This process, often iterative and time-consuming, drastically slows down the cycle of rapid prototyping and scientific exploration. Researchers may spend considerable effort optimizing a solver for a specific scenario, rather than focusing on the underlying scientific question. The lack of automated generalization means that even slight variations in problem setup – changes in geometry, boundary conditions, or physical coefficients – can necessitate a complete re-tuning of the numerical scheme. Consequently, the full potential of PDE-based modeling remains unrealized, as the computational bottleneck often resides not in the physics itself, but in the laborious process of making the simulations run effectively and reliably.

The inherent difficulty in solving partial differential equations (PDEs) is dramatically amplified as the number of variables – the dimensionality – increases. This escalation stems from the ‘curse of dimensionality’, where the computational resources required to achieve a given level of accuracy grow exponentially with each added dimension. Consequently, algorithms must be not only accurate but also remarkably efficient to handle these complex, high-dimensional problems. Robustness becomes paramount; slight variations in initial conditions or parameters can lead to drastically different solutions, demanding algorithms capable of maintaining stability and convergence even under challenging circumstances. Researchers are actively developing techniques like adaptive mesh refinement, sparse grid methods, and machine learning-accelerated solvers to mitigate these challenges, aiming to unlock the potential of PDE-based modeling in fields ranging from fluid dynamics and materials science to financial modeling and climate prediction. The pursuit of scalable and reliable algorithms remains a central focus in computational science, driven by the ever-increasing complexity of the systems under investigation.

Automated Construction: A Multi-Agent System for PDE Solving

AutoNumerics utilizes a multi-agent system to translate natural language descriptions of Partial Differential Equation (PDE) problems into computational frameworks. This system employs Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques and Large Language Models (LLMs) to parse problem statements, identifying key components such as the governing equation, boundary conditions, and domain geometry. The LLM component is responsible for understanding the semantic meaning of the input text, while NLP tools facilitate the extraction of specific parameters and constraints. This automated interpretation process eliminates the need for manual translation of problem descriptions into a form suitable for numerical solver construction, enabling the system to handle a wider range of PDE problems specified in human-readable language.

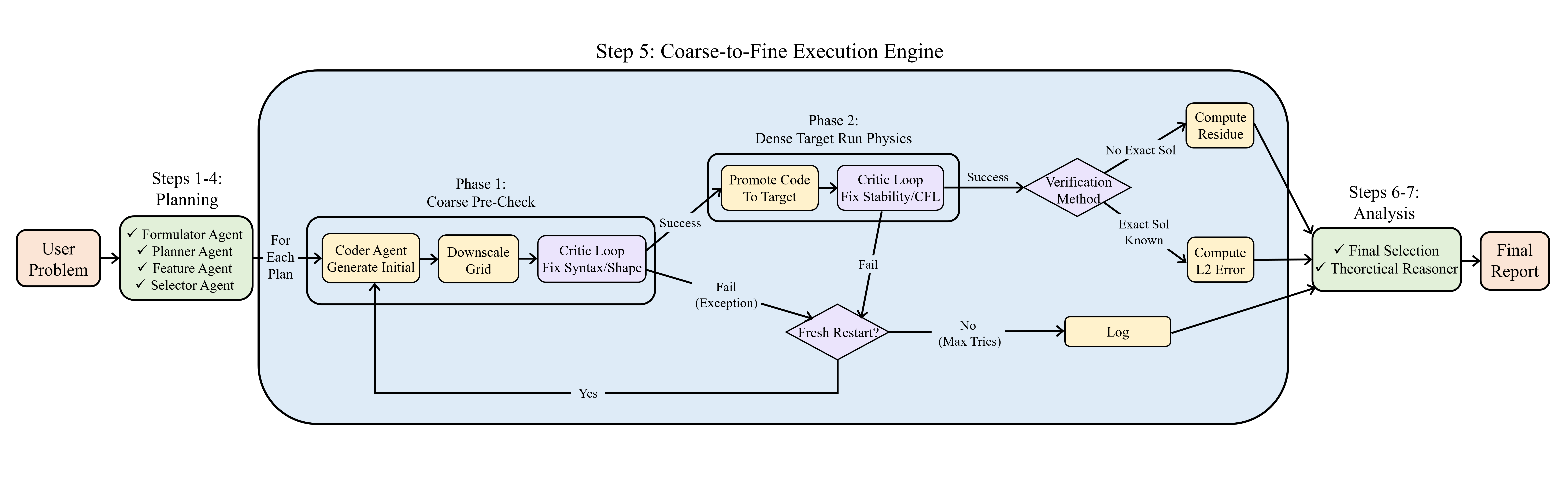

AutoNumerics utilizes a multi-agent system comprised of five specialized agents to automate the construction of numerical schemes. The Formulator agent translates the problem description – typically expressed in natural language – into a formal mathematical representation. The Planner agent then devises a solution strategy, outlining the necessary steps to obtain a numerical solution. A Selector agent identifies appropriate numerical methods and parameters for each step, drawing from a knowledge base of established techniques. The Critic agent evaluates the intermediate results and provides feedback to refine the scheme, while the Coder agent translates the finalized numerical scheme into executable code, typically Python, allowing for immediate simulation and analysis of the [latex]PDE[/latex]. These agents operate collaboratively, iteratively refining the solution until convergence criteria are met.

AutoNumerics demonstrably reduces the time and specialized knowledge needed to develop solutions for complex Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). The system automates the traditionally manual process of numerical scheme construction, achieving complete solver development – encompassing discretization, equation assembly, and code generation – within a timeframe of 20 to 130 seconds for the majority of tested problem instances. This accelerated construction is achieved through a multi-agent framework, minimizing the need for expert-level intervention in both the formulation and coding stages of PDE solution.

Validating Robustness: A Framework for Refinement and Verification

The Planner Agent leverages a suite of established numerical methods for proposing candidate solution schemes. These include Finite Difference methods, applicable to structured grids and approximating derivatives using neighboring cell values; Finite Element methods, which discretize the domain into elements and approximate solutions using piecewise polynomial functions; Spectral methods, utilizing global basis functions like Fourier series for high accuracy; Runge-Kutta methods, a family of explicit and implicit time-stepping methods for ordinary differential equations; and Implicit-Explicit (IMEX) methods, combining implicit and explicit treatments to balance stability and computational cost. The selection of a specific method, or combination thereof, is determined by the characteristics of the partial differential equation being solved and the desired trade-off between accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency.

Coarse-to-fine execution is a debugging strategy implemented to identify and rectify logical errors within the Planner Agent’s proposed schemes prior to computationally expensive high-resolution simulations. This process begins with running the simulation on a low-resolution computational grid, allowing for rapid identification of issues in the core logic without significant resource expenditure. Once validated on the coarse grid, the simulation is scaled to progressively finer resolutions, with each step verifying the continued correctness of the scheme. This iterative refinement ensures that any logical errors are addressed early in the process, preventing their propagation to higher-resolution simulations and minimizing wasted computational resources. The method facilitates efficient debugging by isolating and resolving issues on simplified problem instances before tackling the full complexity of the high-resolution model.

The Critic Agent dynamically addresses issues arising during simulation execution through iterative refinement. This agent employs a suite of techniques, including automatic error detection and corrective action, to maintain solution stability. To optimize performance and prevent non-terminating simulations, two key mechanisms are utilized: Fresh Restart, which discards and regenerates the solution from a stable checkpoint when significant errors accumulate, and History Decimation, which selectively reduces the memory footprint by discarding redundant historical data, thereby minimizing computational overhead and ensuring efficient long-term execution. These features collectively enable the solver to autonomously adapt to complex scenarios and maintain robust performance.

AutoNumerics assesses solution accuracy by quantifying the PDE Residual, which measures the extent to which a computed solution satisfies the governing partial differential equation. This residual-based approach provides a direct verification of solution validity, ensuring adherence to the underlying physics. Benchmarking on the CodePDE dataset demonstrates a geometric mean normalized Root Mean Squared Error (nRMSE) of 9.00×10⁻⁹, indicating high solution fidelity across a range of problems and validating the effectiveness of the residual minimization strategy. This nRMSE value represents the average error relative to the true solution, normalized by the magnitude of the solution itself.

A Paradigm Shift: Expanding the Boundaries of Scientific Inquiry

AutoNumerics represents a paradigm shift in approaching partial differential equation (PDE) solving, enabling researchers to swiftly test hypotheses and explore potential solutions without the traditionally demanding prerequisites of extensive coding or specialized numerical analysis expertise. The framework automates the often laborious process of solver construction and validation, allowing scientists to focus on the physics of their problem rather than the intricacies of implementation. This accelerated prototyping capability is particularly valuable in fields where computational modeling is crucial, such as fluid dynamics and materials science, where iterative refinement and exploration of different approaches are essential for discovery. By drastically reducing the barrier to entry, AutoNumerics empowers a broader range of scientists to leverage the power of computational modeling, fostering innovation and accelerating the pace of scientific advancement.

AutoNumerics introduces a paradigm shift in computational science by automating the traditionally laborious process of solver development and verification. This capability unlocks previously inaccessible research avenues across disciplines reliant on partial differential equations. In fluid dynamics, scientists can now rapidly explore novel designs and flow regimes without dedicating months to code implementation and debugging. Similarly, advancements in heat transfer modeling-from optimizing thermal management in electronics to understanding climate change-become more attainable through quick prototyping and analysis of various scenarios. The framework’s impact extends to materials science, enabling researchers to simulate complex material behavior and accelerate the discovery of new materials with tailored properties – all achieved with a system capable of autonomously building and validating the necessary computational tools.

AutoNumerics represents a substantial shift in the landscape of scientific computing, effectively lowering the threshold for researchers to tackle complex problems described by partial differential equations. This framework empowers scientists across a wider range of disciplines – from materials science to fluid dynamics – to rapidly prototype and investigate solutions without requiring deep expertise in numerical methods or extensive coding. Demonstrating a performance advantage of approximately six orders of magnitude in normalized root mean squared error (nRMSE) when compared to both neural network approaches and the CodePDE system, AutoNumerics doesn’t merely improve upon existing methods, but fundamentally broadens access to powerful computational tools, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery and innovation in diverse fields.

AutoNumerics distinguishes itself from emerging methods like Physics-Informed Neural Networks by grounding its solutions in established numerical analysis, a crucial factor for scientific reliability and predictability. While PINNs leverage the adaptability of neural networks, they often lack guarantees of convergence and can produce solutions with poorly characterized errors; AutoNumerics, conversely, builds upon well-understood techniques, ensuring consistent and predictable behavior. This approach recently demonstrated superior performance, achieving a Relative L2 Error of [latex]10^{-6}[/latex] or better across 11 of 19 test problems possessing known analytical solutions – a level of accuracy that solidifies its potential for applications demanding robust and verifiable results in fields like computational physics and engineering.

AutoNumerics, in its ambition to autonomously construct numerical solvers, embodies a fascinating challenge to the conventional lifecycle of scientific computing systems. The framework doesn’t simply solve equations; it builds a system capable of adaptation and refinement, a crucial element for long-term viability. This mirrors a fundamental tenet of resilient design: every delay is the price of understanding. As Marvin Minsky observed, “You can’t get away from the fact that intelligence is, in a sense, the art of making good choices under uncertainty.” AutoNumerics’ agentic approach, with its residual-based verification, actively seeks to mitigate uncertainty, building a pipeline less prone to the decay inherent in any complex system. It’s not about speed alone, but about fostering a robust architecture capable of graceful aging, a system where each iteration contributes to a deeper understanding of the underlying problem.

What Lies Ahead?

The advent of AutoNumerics, and similar agentic systems, does not signal the resolution of difficulty in scientific computing, but rather a shifting of its locus. Every commit is a record in the annals, and every version a chapter, yet the fundamental challenge remains: the translation of intent into reliable simulation. This framework demonstrably automates portions of the solver construction process, but the verification step – the residual-based check – highlights a critical dependency. It is a humbling reminder that automation, however sophisticated, does not obviate the need for rigorous, independent validation.

Future iterations will inevitably grapple with the brittleness inherent in large language models. The current architecture, while exhibiting competitive performance, operates within a defined scope. Expanding this scope – addressing truly novel PDEs or complex geometries – will necessitate not only increased model capacity but also more robust methods for error detection and correction. Delaying fixes is a tax on ambition, and the field must prioritize building systems capable of self-diagnosis and adaptive refinement.

Ultimately, the long-term success of this approach hinges on its ability to transcend the role of a ‘black box’. Transparency – the capacity to trace the lineage of a solution, to understand why a particular solver was chosen – is paramount. The goal is not merely to obtain an answer, but to build confidence in its veracity – a task that demands a level of interpretability currently beyond the reach of most agentic systems.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17607.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Naomi Watts suffers awkward wardrobe malfunction at New York Fashion Week as her sheer top drops at Khaite show

- Bikini-clad Jessica Alba, 44, packs on the PDA with toyboy Danny Ramirez, 33, after finalizing divorce

2026-02-20 22:41