Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a low-cost, 3D-printed robot arm capable of replicating complex camera movements by learning directly from expert cinematographers.

![The IRIS system cultivates cinematic robot motion by grounding design in task objectives and nurturing a policy-trained solely on real human demonstrations-that seamlessly transfers from simulation to physical execution through a ROS-based control stack and [latex] goal-conditioned [/latex] imitation learning, anticipating future limitations inherent in any engineered system.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.17537v1/x2.png)

This work presents IRIS, a goal-conditioned imitation learning framework for task-specific cinema robots enabling smooth, obstacle-aware visuomotor motion control.

Despite advances in robotic systems, achieving dynamic and repeatable cinematic motion remains hampered by the prohibitive cost and complexity of industrial-grade platforms. This paper introduces ‘IRIS: Learning-Driven Task-Specific Cinema Robot Arm for Visuomotor Motion Control’, a low-cost, 3D-printed robotic system coupled with a goal-conditioned imitation learning framework. By learning directly from human demonstrations via Action Chunking with Transformers, IRIS achieves accurate, perceptually-smooth camera trajectories without explicit geometric programming, all for under $1,000 USD. Could this approach democratize access to sophisticated robotic cinematography and enable new creative possibilities in automated content creation?

The Inevitable Weight of Tradition

For decades, the art of filmmaking relied on substantial, manually operated camera rigs. These systems, often requiring a dedicated team to manage and move, presented significant logistical and financial hurdles for productions of all sizes. Beyond the sheer physical weight and space demands, the cost of acquisition and maintenance, coupled with the need for highly trained camera operators, limited creative flexibility and accessibility. Achieving complex shots – smooth tracking, precise pans, and dynamic movements – demanded years of experience and a deep understanding of both the equipment and the nuances of cinematic storytelling. This traditional workflow, while yielding iconic imagery, inherently restricted experimentation and presented a barrier to entry for emerging filmmakers and independent projects.

The pursuit of automated cinematic camera movement presents a complex engineering hurdle, extending far beyond simply replicating human operation. While robotic arms can achieve precise positioning, translating that precision into the fluid, organic motions expected in film requires overcoming significant challenges in trajectory planning and execution. Current systems often struggle with the subtle accelerations, decelerations, and minute corrections that a skilled camera operator instinctively performs, resulting in footage that appears mechanical or lacking in artistic nuance. Moreover, repeatability – consistently recreating a complex camera move for reshoots or visual effects integration – proves difficult due to the accumulation of small errors and the inherent variability in robotic systems. Truly flexible automation demands not just precision, but also the capacity to adapt to changing scene requirements and artistic direction, necessitating advanced control algorithms and potentially, machine learning approaches to mimic the creativity of a human cinematographer.

Current robotic camera systems, while demonstrating advancements in automation, frequently fall short of the nuanced demands of cinematic practice. The core issue lies in a trade-off between industrial robotic precision – optimized for repeatable tasks like welding or assembly – and the fluid, organic movements expected in filmmaking. Existing solutions often exhibit jerky motions or lack the subtle dexterity to execute complex camera moves, such as smooth tracking shots, graceful arcs, or quick, precise pans. This limitation stems from factors like actuator speed, joint flexibility, and the ability to compensate for vibrations or external disturbances. Consequently, achieving a truly cinematic aesthetic – one that prioritizes both technical accuracy and artistic expression – remains a considerable hurdle for automated systems, necessitating ongoing research into more adaptable and agile robotic platforms.

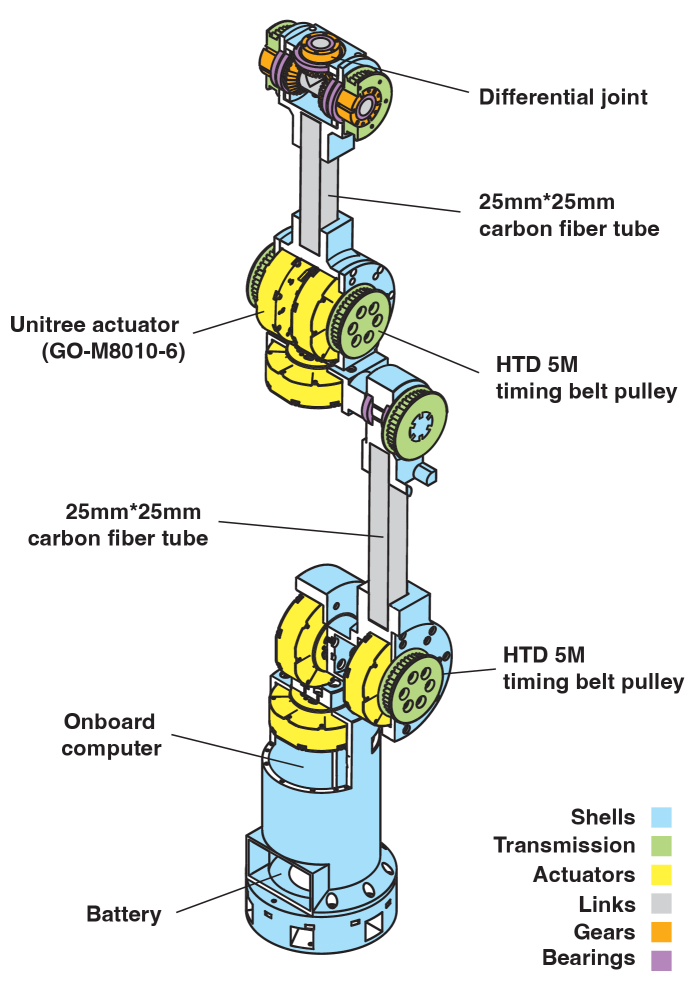

A Platform Born of Purpose

The IRIS robot platform is a six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) system engineered for cinematic camera control, prioritizing dynamic movement capabilities. Unlike many camera robots which repurpose industrial arms, IRIS is designed specifically for this application, resulting in a significantly reduced cost of approximately $1000 per unit. This compact design facilitates integration into various production environments and allows for complex camera trajectories previously unattainable at this price point. The robot’s physical characteristics and control architecture are tailored to the demands of filmmaking, focusing on smooth, repeatable, and precisely controlled movements for professional-quality cinematography.

Unlike many cinema robots built from repurposed industrial arms, IRIS prioritizes hardware specifically engineered for dynamic camera work. Traditional industrial manipulators are optimized for payload capacity and repeatability in static, pick-and-place scenarios, necessitating significant modification to achieve the required speed, smoothness, and backdrivability for cinematic motion. IRIS’s design circumvents these limitations by focusing on lightweight materials, a tailored kinematic structure, and actuation methods – such as Quasi-Direct Drive – directly suited to the demands of precise, fluid camera control. This task-specific approach results in a robot with a demonstrably higher performance-to-cost ratio for cinematic applications compared to adapted industrial solutions.

The IRIS robot utilizes a Quasi-Direct Drive (QDD) actuation system, a method prioritizing high torque density and backdrivability. Unlike traditional geared systems, QDD employs a low-ratio gearbox – typically 3:1 or 5:1 – coupled directly to a brushless DC motor. This configuration minimizes backlash and transmission errors while maintaining a substantial torque output relative to the robot’s size and weight. The reduced gear ratio also facilitates backdrivability, enabling external forces to readily move the robot arm, which is crucial for safe human-robot interaction and responsive dynamic camera control. This contrasts with heavily geared systems that exhibit higher holding torque but reduced responsiveness and increased friction.

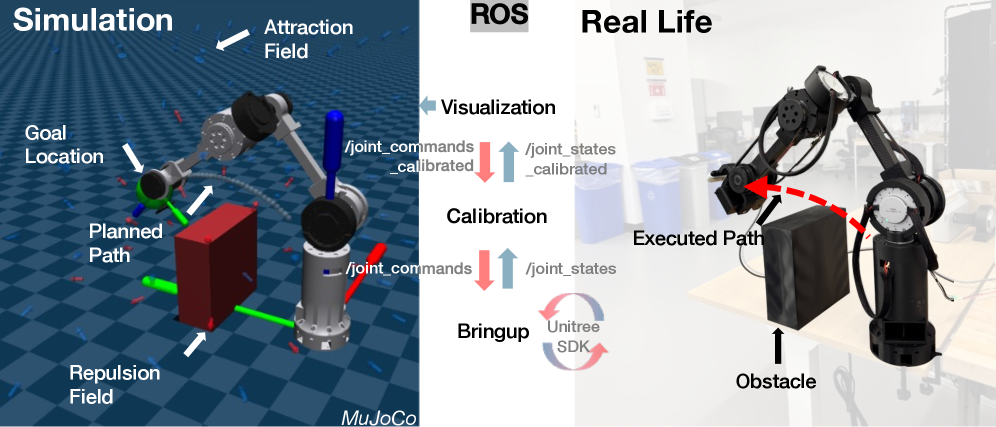

The Robot Operating System (ROS) serves as the central framework for the IRIS cinema robot, enabling cohesive control over its hardware and software components. ROS facilitates communication between the robot’s six-degree-of-freedom (6-DOF) arm, its Quasi-Direct Drive (QDD) actuators, and higher-level motion planning and camera control algorithms. This integration is achieved through ROS’s node-based architecture, allowing for modular development and easy expansion of functionality. Specifically, ROS handles real-time control loops, inverse kinematics calculations, and the transmission of commands to the QDD actuators, while also providing tools for data logging, visualization, and remote operation. The use of ROS ensures compatibility with a wide range of existing robotics software packages and development tools, simplifying the development process and fostering community contributions.

Learning from Ghosts: The Imitation of Motion

Goal-Conditioned ACT Learning builds upon the Action Chunking with Transformers (ACT) framework by incorporating obstacle awareness into learned camera motion. This is achieved by conditioning the ACT model on environmental geometry, allowing it to plan trajectories that actively avoid collisions with static and dynamic obstacles. The system leverages a visual goal signal, combined with obstacle information, as input to the Transformer network, which then predicts a sequence of camera actions. This approach enables the creation of cinematic camera movements within complex environments, going beyond purely trajectory-based action replication and allowing for reactive path planning during execution.

Visual goal conditioning directs the learning of cinematic camera motion by utilizing goal images as target states for trajectory prediction. The system accepts an image representing the desired final camera view as input, and subsequently learns to generate the necessary camera movements to achieve that view. This process effectively frames the problem as a visual servoing task, where the learned policy attempts to minimize the difference between the current camera view and the provided goal image. The goal image provides direct visual feedback, guiding the learning algorithm to produce camera trajectories that converge on the desired aesthetic outcome, allowing for intuitive control over the learned cinematic behaviors.

The presented system utilizes Imitation Learning (IL) as a foundational methodology, specifically building upon established techniques such as Behavior Cloning (BC) and Dataset Aggregation (DAgger). Behavior Cloning involves training a policy directly from expert demonstrations, mapping observed states to actions. However, BC is susceptible to compounding errors when encountering states not present in the training data. To mitigate this, Dataset Aggregation (DAgger) iteratively improves the policy by querying the expert for actions on states visited by the learned policy, thereby expanding the training dataset and reducing distribution shift. This iterative process allows the system to generalize beyond the initially provided demonstrations and achieve more robust performance in dynamic environments.

During low-level control evaluation, the implemented system demonstrates sub-millimeter repeatability, indicating a high degree of precision in replicating camera movements. Tracking accuracy reaches the centimeter scale, confirming the system’s ability to follow desired paths with minimal deviation. This performance is facilitated by a Conditional Variational Autoencoder (CVAE) which models the multimodal distribution of cinematic styles; the CVAE allows the system to generate diverse, yet coherent, camera trajectories by sampling from a learned latent space representing various aesthetic choices and movement patterns.

![The IRIS policy utilizes a ResNet-18 and transformer decoder to predict a 15-step joint trajectory [latex]\hat{q}_{t+1:t+H}[/latex] conditioned on observation history, a goal image, and a latent style token derived from the ground-truth trajectory during training, but operates deterministically at inference by removing the latent style input.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.17537v1/x5.png)

The Inevitable Convergence: Validation and Future Visions

Rigorous testing of the complete robotic system on physical hardware has definitively established its capacity for fluid, consistent, and safe camera movements. The implementation successfully navigates dynamic environments, demonstrating reliable obstacle avoidance while maintaining a smooth operational trajectory. This end-to-end validation-encompassing perception, planning, and control-confirms the system isn’t merely a simulation, but a functional robotic platform capable of executing complex cinematic maneuvers in the real world. The achieved performance suggests a viable path toward automating camera work, offering precision and repeatability previously unattainable without significant human effort.

The IRIS system demonstrated a high degree of precision in visual alignment during trials, successfully completing 83% of push-in tasks performed without obstructions. Even when presented with obstacles requiring active avoidance, the system maintained a commendable 75% success rate in aligning the camera as intended. These figures highlight the robustness of the control algorithms and the effectiveness of the integrated perception and motion planning components, suggesting a capacity for reliable operation in dynamic and potentially cluttered environments. The performance metrics establish a strong foundation for applications demanding accurate and adaptable camera positioning, particularly within the context of automated cinematic capture.

Achieving fluid, cinematic camera movements requires more than just accurate positioning; it demands exceptional smoothness. The IRIS system maintains a remarkably low jerk – the rate of change of acceleration – of 0.05 m/s³. This metric directly correlates to perceived motion quality, ensuring that camera movements are not jarring or distracting to viewers. A value this low signifies that the robotic arm accelerates and decelerates gradually, mimicking the natural fluidity of a skilled camera operator and minimizing unwanted vibrations that can plague robotic systems. Maintaining such Cartesian smoothness is critical for producing professional-quality footage and represents a significant advancement in robotic cinematography, allowing for complex shots without the telltale signs of mechanical movement.

The development of IRIS benefits significantly from a sophisticated simulation environment built within the MuJoCo physics engine, allowing for extensive testing and refinement of robotic control strategies. This virtual space facilitates rapid iteration on algorithms, bypassing the time and resource constraints of purely physical experimentation. Crucially, performance within MuJoCo is benchmarked against the Rapidly-exploring Random Tree star (RRT) algorithm, a well-established motion planning technique. This comparative analysis ensures that IRIS’s control systems not only function effectively but also demonstrate improvements over existing methodologies, particularly in complex scenarios demanding both efficiency and adaptability. The robust nature of the MuJoCo simulation, coupled with RRT validation, accelerates the pathway to real-world deployment by proactively identifying and addressing potential challenges before they manifest in physical hardware.

The development of IRIS signals a potential democratization of cinematic robotics, previously limited by cost and complexity. This system distinguishes itself through a focus on accessibility, demonstrating that high-quality, repeatable camera motion – crucial for professional filmmaking – can be achieved with a relatively streamlined robotic platform. By integrating robust obstacle avoidance and maintaining smooth Cartesian motion at 0.05 m/s³, IRIS offers a compelling alternative to traditional, and often cumbersome, motion control systems. Validation on physical hardware, coupled with a strong visual alignment success rate – 83% for unobstructed tasks and 75% with obstacles – confirms its practicality and reliability, suggesting a future where sophisticated robotic cinematography is within reach for a broader range of creators and productions.

The creation of IRIS speaks to a fundamental truth about complex systems: attempts at rigid control are ultimately transient. This robot, born from 3D printing and imitation learning, doesn’t strive for absolute precision, but rather adapts and refines its movements based on demonstrated examples. As Claude Shannon observed, “The most important thing in communication is to convey the right message, not necessarily the most accurate one.” IRIS embodies this sentiment; its goal-conditioned learning prioritizes achieving the effect of smooth, obstacle-aware motion – a fluid cinematic result – over meticulous adherence to pre-programmed instructions. Each demonstration is a promise made to the past, shaping the robot’s future trajectory, and everything built will one day start fixing itself as IRIS learns and improves with each iteration.

The Looming Dependence

The presentation of IRIS, a readily fabricated robot trained through demonstration, suggests a narrowing of focus. The ease of replication is not a victory over complexity, but an invitation to it. Each successful imitation learning framework becomes a new dependency, a tightly coupled link in a chain destined to strain. The robot learns to mimic, and in doing so, embodies the limitations of its teacher, amplifying them across countless identical bodies. The system does not solve the problem of motion, it distributes the inevitability of error.

The emphasis on task-specific hardware, while pragmatic, implies a fracturing of generalizability. Each specialized robot accumulates a unique set of frailties, a bespoke path toward eventual failure. The illusion of progress is sustained only by the constant creation of new, equally vulnerable systems. Trajectory optimization, goal-conditioned learning – these are merely local optimizations within a globally entropic process.

The future will not be filled with versatile robots, but with a vast archipelago of brittle automatons, each exquisitely adapted to a narrow task, and increasingly reliant on the continued existence of the entire network. The smoothness of the motion is not the point. It is the smoothness of the fall that truly defines the system.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17537.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Honkai: Star Rail Version 4.0 Phase One Character Banners: Who should you pull

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Lana Del Rey and swamp-guide husband Jeremy Dufrene are mobbed by fans as they leave their New York hotel after Fashion Week appearance

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

2026-02-20 15:35