Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework unifies data and computation, empowering researchers to create reliable and scalable scientific workflows.

DataJoint 2.0 introduces a relational workflow model for enhanced data provenance, integrity, and computational reproducibility.

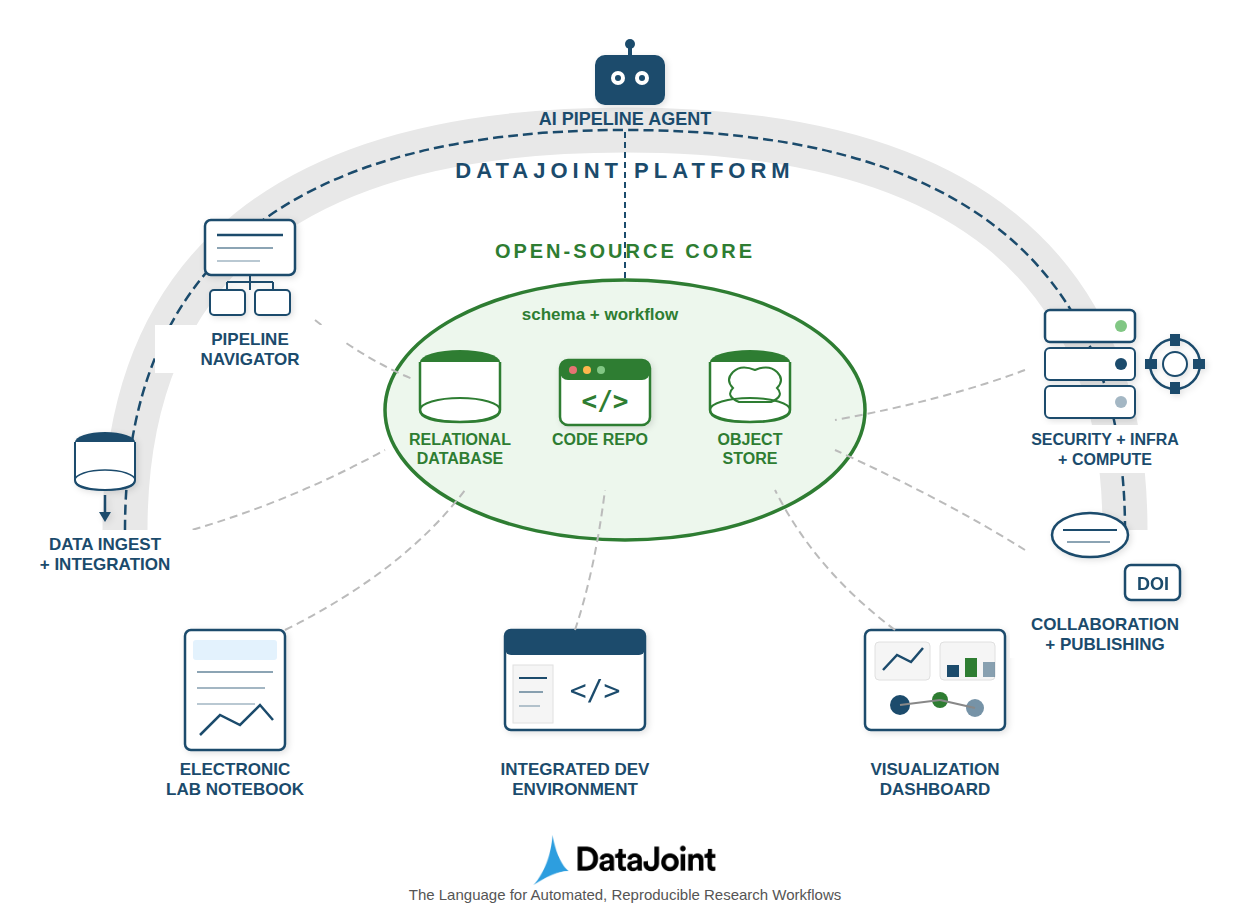

Achieving rigorous data provenance remains a central challenge in modern scientific workflows, often fragmented across disconnected systems. This limitation motivates the work presented in ‘DataJoint 2.0: A Computational Substrate for Agentic Scientific Workflows’, which introduces a relational workflow model to unify data structure, data, and computational transformations. By representing workflow steps as relational tables and leveraging innovations like object-augmented schemas and semantic matching, DataJoint 2.0 enables a queryable, enforceable system for data integrity and reproducibility. Will this approach fundamentally reshape how scientists design and execute complex, collaborative experiments with increasing reliance on automated agents?

The Data Flood: Why Everything is Broken

The accelerating pace of discovery is unleashing a data deluge upon the scientific community, rapidly eclipsing the capabilities of conventional data management systems. Advances in areas like genomics, astronomy, and climate modeling now routinely generate datasets measured in terabytes and petabytes – a scale previously unimaginable. Traditional file-based approaches, designed for smaller, static datasets, struggle to handle this volume, velocity, and variety of information. This poses significant challenges not only for storage and access but also for ensuring data integrity, version control, and efficient analysis. The sheer quantity of data threatens to overwhelm researchers, hindering their ability to extract meaningful insights and potentially slowing the rate of scientific progress, demanding innovative solutions for effective data handling and curation.

Traditional file-based systems, while historically sufficient, now present significant hurdles to contemporary scientific research. These systems often rely on manual tracking of data provenance – the history of how data is generated and modified – which is prone to errors and makes it difficult to ensure data integrity. This lack of automated tracking directly impacts reproducibility, as researchers struggle to recreate analyses with confidence when the precise steps and data versions are unclear. Moreover, modern analyses frequently involve complex pipelines with numerous interdependent steps and large datasets, exceeding the organizational capacity of simple file structures. Consequently, researchers spend considerable time managing data rather than interpreting results, and the potential for subtle, difficult-to-detect errors increases, ultimately hindering scientific progress and reliable discovery.

The escalating complexity of scientific research demands a fundamental shift in how data and workflows are managed. Current systems, often built around simple file transfers, are increasingly inadequate for ensuring the integrity and reproducibility of results, particularly as analyses involve intricate pipelines and massive datasets. A robust system isn’t simply about storage capacity; it requires verifiable provenance – a complete and auditable record of data transformations – to establish trust in scientific findings. Scalability is equally crucial, allowing researchers to handle ever-growing data volumes without compromising performance or accuracy. Ultimately, a provably correct system, one that can mathematically guarantee the reliability of its operations, represents the gold standard for modern scientific workflow management, fostering collaboration and accelerating discovery by eliminating ambiguity and ensuring the trustworthiness of research outcomes.

Relational Workflows: A Sensible Structure, Finally

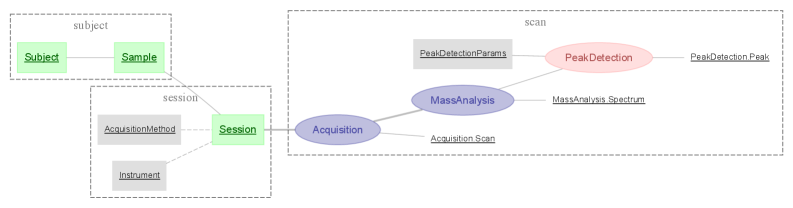

The Relational Workflow Model structures workflow management by defining each workflow step as a dedicated database table. Individual instances of the artifact being processed-documents, images, data records, etc.-are represented as rows within these tables. Crucially, the sequence in which these artifacts move through the workflow is determined by foreign key relationships between tables; a foreign key in a subsequent step’s table references the primary key of the artifact’s row in the preceding step, effectively establishing the execution order and providing a complete audit trail. This abstraction enables efficient querying, reporting, and analysis of workflow progress and artifact status, while also facilitating parallel processing and branching logic.

Workflow Normalization is achieved by structuring data such that each entity is represented as a row in a database table corresponding to its current stage within the defined workflow. This granular representation prevents data redundancy and ensures consistency as an entity progresses; updates occur in a single row reflecting its status. By explicitly associating each entity with a specific workflow stage, complex analyses, such as identifying bottlenecks or tracking entity lifecycles, are simplified through standard SQL queries and aggregations. This method facilitates accurate reporting on work-in-progress and enables precise measurement of cycle times at each stage of the process.

The Relational Workflow Model is built upon established data storage technologies – SQL databases and object storage – to provide both ease of adoption and scalability. SQL databases manage the metadata defining the workflow – step definitions, artifact properties, and execution history – utilizing their inherent capabilities for relational data management, querying, and transaction support. Concurrently, object storage systems are used to store the actual artifacts progressing through the workflow, offering cost-effective and highly scalable storage for potentially large binary or unstructured data. This dual-storage strategy allows organizations to leverage existing database expertise and infrastructure while benefiting from the virtually limitless scalability of object storage, facilitating workflow management for both small-scale and large-scale applications.

DataJoint: A System That Doesn’t Immediately Fall Apart

DataJoint utilizes the Relational Workflow Model, structuring data access and processing as a series of interconnected operations defined by a schema. This schema isn’t limited to traditional relational database constraints; it’s object-augmented, meaning it incorporates metadata and definitions for complex data types beyond simple tables. Consequently, DataJoint can integrate data residing in disparate storage systems – including relational databases, NoSQL stores, cloud storage, and even flat files – by mapping them to this unified, schema-defined structure. This allows users to query and process data across these diverse sources as if they were a single, coherent dataset, abstracting away the underlying storage complexities and promoting interoperability.

DataJoint’s automated job management system operates by analyzing dependencies defined within the data schema. Jobs, representing data processing or analysis steps, are automatically scheduled and executed in the correct order based on these schema-defined relationships; a job will only run once all prerequisite data, as specified in the schema, is available. This dependency-driven approach eliminates manual scheduling errors and ensures efficient resource utilization by preventing unnecessary computations until required inputs are present. The system dynamically determines the execution order, parallelizing independent jobs where possible to minimize processing time and optimize throughput, thereby streamlining complex data workflows.

Semantic Matching within DataJoint operates by verifying data consistency across relational tables based on declared schemas and types, effectively acting as a continuous validation process. This matching generates a Lineage Graph, a directed acyclic graph that maps the complete history of data transformations, from raw data sources to derived results. Each node represents a dataset, and edges denote the specific operations performed to create that dataset, including the code used and the user responsible. This detailed provenance tracking is critical for reproducibility, allowing researchers to precisely reconstruct any result and verify its origins, and facilitates debugging and error tracing by pinpointing the source of data inconsistencies.

The Future: SciOps and Workflows That Don’t Require Prayer

DataJoint addresses the challenges of managing increasingly complex datasets through its innovative Master-Part relationships. This framework enables researchers to decompose large, monolithic datasets into smaller, interconnected components – the ‘Parts’ – which are logically linked to a central ‘Master’ dataset. This decomposition isn’t merely organizational; it fundamentally alters how data is accessed and analyzed, allowing for targeted queries that retrieve only the necessary information. Consequently, analyses become significantly faster and more efficient, especially when dealing with datasets spanning multiple experiments, subjects, or time points. The approach also promotes data integrity by ensuring that all Parts remain consistent with their Master, mitigating errors and facilitating reproducibility – a crucial aspect of modern scientific workflows. By effectively mirroring the hierarchical structure often inherent in scientific data, DataJoint empowers researchers to navigate and extract insights from complex information with greater ease and reliability.

DataJoint’s adaptable type system represents a significant advancement in handling the diverse and often complex data formats inherent in modern scientific research. Rather than rigidly enforcing a single data structure, the system allows researchers to define custom types that seamlessly integrate with domain-specific formats – from neurophysiological recordings and genomic sequences to microscopy images and behavioral data. This flexibility isn’t merely about convenience; it directly addresses the challenges of scalability by enabling efficient data storage, retrieval, and analysis, even with massive datasets. By accommodating specialized data representations, the system minimizes data conversion bottlenecks and ensures that information remains readily accessible and interpretable throughout the entire scientific workflow, fostering reproducible and efficient research practices.

The core of this new framework lies in a relational workflow model, fully realized in DataJoint 2.0, designed to ensure data integrity throughout complex scientific pipelines. Unlike traditional approaches prone to inconsistencies, this system employs transactional guarantees-essentially, an ‘all or nothing’ commitment-for every data operation. This means that any step within a workflow, from initial acquisition to final analysis, either completes successfully as a unified whole or fails entirely, preventing partial updates and corrupted datasets. By rigorously enforcing these constraints, DataJoint 2.0 dramatically reduces the potential for errors and ensures reproducibility, a critical benefit for collaborative science and long-term data archiving. The system essentially builds a robust audit trail, making it possible to trace data lineage and pinpoint the source of any discrepancies, fostering greater confidence in research findings.

The pursuit of a unified computational substrate, as DataJoint 2.0 attempts with its relational workflow model, feels… ambitious. It’s a tidy vision – data, structure, and transformations all elegantly interwoven. One suspects, however, that production environments will swiftly reveal edge cases the designers hadn’t anticipated. As Marvin Minsky observed, “The question isn’t whether a machine can think, but whether it can do useful things.” This system strives for a beautiful architecture, but the real test lies in its ability to withstand the inevitable onslaught of real-world data and the messy demands of scientific inquiry. It’s a lovely abstraction, and one predicts it will, eventually, become a very specific form of tech debt. The focus on data provenance is admirable, though; at least future digital archaeologists will have something to excavate when it all inevitably crumbles.

What’s Next?

The presented framework addresses the perennial problem of scientific data management by, essentially, building a more elaborate database. The claim of supporting “agentic workflows” is merely an articulation of existing automation principles, rebranded for a data-centric audience. The true test will not be in elegant schema design, but in the inevitable accumulation of edge cases and the compromises made when real-world experimental realities collide with relational purity. The system’s reliance on a queryable framework is a strength, but also a potential bottleneck – a single point of failure for scalability, disguised as a feature.

Future work will inevitably focus on integration-connecting this relational model to the existing patchwork of tools scientists already employ. This is not innovation, but rather the endless task of translating between incompatible systems. The emphasis on data provenance is laudable, yet provenance alone does not guarantee reproducibility; it merely offers a more detailed post-mortem analysis when things inevitably break. The question isn’t whether the system can track lineage, but whether scientists will diligently maintain it.

Ultimately, the field doesn’t need more abstractions – it needs fewer illusions. The promise of a unified computational substrate is appealing, but history suggests every architecture becomes a punchline, every elegant solution a source of technical debt. The challenge remains: not to build a perfect system, but to accept that imperfection is inherent, and to design for graceful degradation when the inevitable cracks appear.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16585.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Honkai: Star Rail Version 4.0 Phase One Character Banners: Who should you pull

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

- Lana Del Rey and swamp-guide husband Jeremy Dufrene are mobbed by fans as they leave their New York hotel after Fashion Week appearance

2026-02-20 03:50