Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages fundamental physical laws to train artificial intelligence, dramatically improving its ability to solve complex scientific problems with limited data.

Incorporating physics knowledge into neural operator training enhances data efficiency, prediction consistency, and generalization across diverse partial differential equation problems.

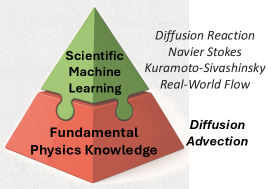

Despite advances in scientific machine learning, neural operator training often overlooks the foundational physical principles governing modeled systems. This work, ‘Learning Data-Efficient and Generalizable Neural Operators via Fundamental Physics Knowledge’, introduces a multiphysics training framework that enhances data efficiency and generalization by jointly learning from both partial differential equations and their simplified forms. Our results demonstrate that explicitly incorporating fundamental physics knowledge significantly improves predictive accuracy and out-of-distribution performance across a range of problems. Could this approach unlock more robust and reliable physics-informed machine learning models capable of tackling complex, real-world phenomena?

Deconstructing Reality: The Limits of Traditional Simulation

Many advancements across scientific and engineering disciplines rely on modeling physical phenomena with [latex] \partial u / \partial t = \nabla \cdot D \nabla u [/latex] Partial Differential Equations (PDEs); however, established numerical techniques for solving these equations face significant challenges when dealing with intricate real-world scenarios. Traditional methods, such as finite differences or finite elements, often become computationally prohibitive as the number of dimensions increases – a phenomenon known as the “curse of dimensionality”. Similarly, representing complex geometries – think of airflow around an airplane wing or heat transfer in an irregularly shaped engine component – requires exceedingly fine meshes, dramatically increasing the computational cost and memory requirements. This limitation restricts the ability to accurately simulate and predict behavior in many crucial applications, necessitating the development of more efficient and scalable solution strategies.

Traditional numerical solvers for Partial Differential Equations (PDEs) often demand substantial computational resources, particularly as problem complexity increases – a limitation stemming from the need to discretize the continuous solution domain into a vast number of grid points. This discretization, while necessary, scales rapidly with dimensionality, quickly exceeding the capabilities of even high-performance computing systems. Consequently, achieving convergence – the point at which the solution stabilizes and becomes reliable – can be exceedingly slow, sometimes requiring days or even weeks for a single simulation. This sluggishness directly impedes applications requiring rapid responses, such as real-time control systems, dynamic optimization processes, and interactive simulations where immediate feedback is crucial. The computational bottleneck therefore restricts the feasibility of exploring a wider parameter space or conducting extensive sensitivity analyses, ultimately hindering a thorough understanding of the modeled phenomena.

Traditional PDE solvers, while effective within defined parameters, often exhibit a limited capacity for generalization. The predictive power of these methods is frequently constrained by their reliance on training data; a solver proficient at simulating fluid dynamics around a specific airfoil, for example, may perform poorly when presented with a significantly different shape or flow condition. This inflexibility arises from the solver’s learned approximations-it essentially memorizes solutions for encountered scenarios rather than developing a robust understanding of the underlying physical principles. Consequently, extrapolating beyond the scope of the training data can lead to substantial inaccuracies and unreliable predictions, necessitating either extensive retraining or the development of more adaptable solution strategies. This limitation is particularly problematic in fields requiring robust performance across a wide range of operating conditions, such as weather forecasting or materials science.

![Our method leverages decomposed partial differential equations [latex]\partial/\partial t[/latex] to encode physical knowledge, enabling cheaper simulations and improving the performance of neural operators through joint training on both the full and decomposed equations.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.15184v1/x3.png)

Rewriting the Rules: Scientific Machine Learning as a New Paradigm

Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) distinguishes itself from traditional machine learning by explicitly incorporating governing physical laws and domain expertise into model development. Rather than relying solely on data-driven learning, SciML methods leverage known physics – expressed as differential equations, conservation laws, or other constraints – to guide the learning process. This integration often manifests as incorporating physics-based loss functions, employing specialized neural network architectures designed to respect physical principles, or utilizing symbolic regression to rediscover known equations from data. The result is models that require less training data, generalize more effectively to unseen scenarios, and provide more interpretable and physically plausible predictions compared to purely data-driven approaches. This is particularly valuable in scientific and engineering domains where data is often limited, noisy, or expensive to acquire, and where adherence to physical constraints is paramount.

Neural Operators represent a class of machine learning models designed to approximate the solution operator of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). Unlike traditional methods that discretize the domain and solve for values at discrete points, Neural Operators learn a mapping between function spaces – specifically, a mapping from a space of input functions (e.g., initial conditions, boundary conditions) to a space of output functions (the solution to the PDE). This is achieved through the use of neural networks with architectures designed to enforce certain properties, such as universal approximation capabilities for function spaces. By learning this mapping directly, Neural Operators can generalize to unseen data and handle complex geometries without requiring retraining, and can often achieve solutions with significantly fewer computational resources compared to finite element or finite difference methods. The output of a Neural Operator is a function [latex] u(x) [/latex] representing the solution to the PDE, given an input function [latex] f(x) [/latex] defining the problem.

Traditional numerical methods for solving partial differential equations (PDEs) typically discretize the solution domain into a grid, requiring significant computational resources as grid resolution increases. Neural Operators, in contrast, learn the mapping between the input function space and the output function space directly, representing the solution as a continuous function. This approach bypasses the need for explicit gridding, enabling generalization to previously unseen geometries and boundary conditions without retraining. Because the solution is represented continuously, the operator learns the underlying physics rather than memorizing discrete values, facilitating accurate predictions on complex domains and reducing computational cost associated with high-resolution simulations.

Traditional numerical methods for solving partial differential equations (PDEs), compared to Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) approaches, particularly those utilizing Neural Operators, demonstrate the potential for substantial performance gains. Traditional solvers, such as finite element or finite difference methods, often require increasingly fine discretizations of the problem domain to achieve higher accuracy, leading to significant computational cost and memory requirements. SciML methods, by learning the underlying operator directly, can approximate solutions with fewer computational resources and maintain accuracy even with limited data. Benchmarks have shown speedups ranging from 10x to 100x in certain applications, and improved accuracy, especially when dealing with high-dimensional or complex geometries where traditional methods struggle with the curse of dimensionality. Furthermore, SciML methods can often generalize to unseen data or parameter variations more effectively than traditional solvers, reducing the need for repeated simulations.

Exploiting the System: Leveraging Physics for Robust Generalization

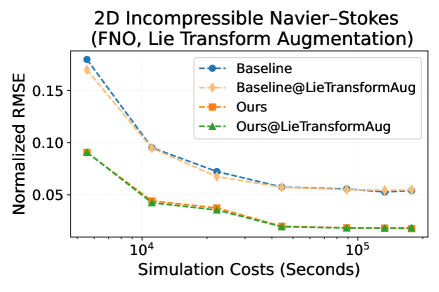

Integrating fundamental physical knowledge, specifically Lie symmetry, into Neural Operator architectures provides a mechanism for data augmentation and enhances out-of-distribution generalization capabilities. Lie symmetry identifies transformations of the input space that leave the underlying physical laws invariant; exploiting these symmetries allows the model to generate new, physically plausible training examples from existing data. This effectively expands the training dataset without requiring additional simulations or experiments. Consequently, the model learns a more robust and generalizable representation of the physical system, leading to improved performance when applied to scenarios outside the original training distribution. The incorporation of these symmetries provides the network with inherent inductive biases aligned with the governing physics, improving extrapolation to unseen conditions.

Exploiting inherent symmetries within physical systems enables neural networks to generalize beyond the training data distribution. This extrapolation capability arises because symmetries define invariances – properties that remain constant under specific transformations. By encoding these invariances into the model architecture, the network learns to represent the underlying physics in a way that is independent of irrelevant variations in the input space. Consequently, the model can accurately predict system behavior even when presented with scenarios not explicitly encountered during training, effectively reducing the need for extensive data coverage and improving performance on out-of-distribution data.

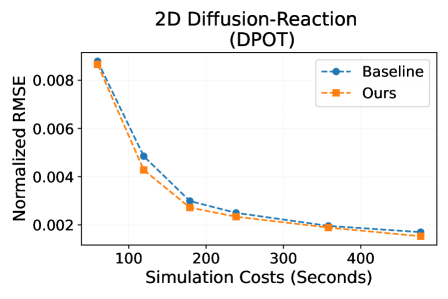

Employing simplified Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), designated as BasicPDEForm, facilitates the isolation of essential dynamic characteristics while concurrently decreasing computational demands. This simplification involves reducing the order of the PDE or eliminating non-essential terms, resulting in a model that captures the dominant behaviors of the system with fewer parameters and operations. The use of these simplified forms allows for more efficient training and inference, as the computational cost scales with the complexity of the governing equation. This approach doesn’t necessarily sacrifice accuracy; by focusing on core dynamics, it can improve generalization and reduce the need for extensive datasets or high-fidelity simulations.

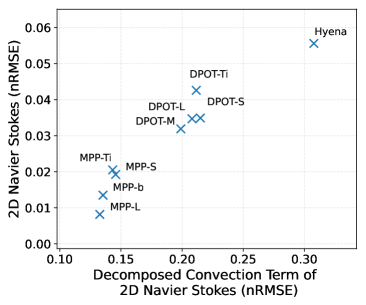

Incorporating fundamental physics knowledge into neural operator architectures demonstrably improves predictive accuracy, as evidenced by reductions in Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (nRMSE) of up to 24% when compared to baseline models lacking such integration. This performance gain has been specifically observed across benchmark problems involving 2D Diffusion-Reaction and 2D Navier-Stokes equations. The nRMSE metric quantifies the average magnitude of the error relative to the magnitude of the true value, providing a standardized measure of prediction accuracy; the reported reduction indicates a significant improvement in the model’s ability to accurately simulate these physical systems.

Employing simplified forms of governing partial differential equations (PDEs) during model training enables a substantial reduction in computational expense. This is achieved by strategically reallocating the simulation budget; rather than increasing simulation fidelity or dataset size, resources are conserved through the use of lower-complexity models. Specifically, training on these simplified forms yields a 50% decrease in required simulation costs, allowing for the same predictive power with significantly less computational demand. This approach doesn’t compromise accuracy, but rather optimizes resource utilization by focusing on core dynamic principles rather than high-resolution detail during the training phase.

Beyond Prediction: The Future of Scientific Computing

The landscape of scientific discovery is undergoing a transformation with the advent of large-scale foundation models, such as DPOT, trained on a diverse array of partial differential equations (PDEs). These models, akin to those driving advances in artificial intelligence, learn underlying patterns from vast datasets of physical simulations, enabling them to predict and even accelerate complex phenomena. Unlike traditional methods requiring bespoke solutions for each problem, these pre-trained models offer a generalized framework applicable to a wide spectrum of scientific challenges. This approach allows researchers to bypass computationally expensive simulations, rapidly explore design spaces, and ultimately gain deeper insights into the behavior of physical systems – from the intricacies of fluid dynamics described by the Navier-Stokes equations [latex] \nabla \cdot \mathbf{v} = 0 [/latex] to the complex interactions governing material properties and climate patterns. The emergence of these models signals a shift toward data-driven scientific exploration, promising to unlock new possibilities and accelerate the pace of innovation.

The advent of large-scale foundation models is dramatically reshaping the landscape of scientific computing by offering unprecedented capabilities in simulation speed, design optimization, and predictive accuracy. These models, trained on vast datasets of physical phenomena, can bypass computationally expensive traditional methods, achieving results orders of magnitude faster-allowing for exploration of previously inaccessible parameter spaces. Beyond acceleration, they excel at optimizing complex designs, identifying ideal configurations for everything from aerodynamic structures to novel materials, guided by learned relationships between form and function. Perhaps most powerfully, these models facilitate real-time predictions, crucial for applications like weather forecasting, personalized medicine, and adaptive control systems, where timely insights are paramount. This shift isn’t merely about faster computing; it represents a fundamental change in how scientific problems are approached, moving from reactive analysis to proactive prediction and intelligent design.

The convergence of Neural Operators and Scientific Machine Learning (SciML) represents a paradigm shift in computational science, poised to dramatically accelerate progress across diverse fields. Neural Operators, capable of learning the mapping between functions, offer a powerful alternative to traditional discretization-based methods for solving partial differential equations (PDEs). When coupled with SciML – which integrates physics-based knowledge and data-driven techniques – these models can not only predict physical phenomena with greater accuracy and efficiency but also generalize to unseen scenarios with limited data. This synergistic approach holds particular promise for traditionally computationally intensive areas like fluid dynamics, where simulating turbulent flows is a longstanding challenge, materials science, enabling the discovery of novel materials with tailored properties, and climate modeling, facilitating more precise long-term predictions and a better understanding of complex climate systems. By bridging the gap between data and physics, this combination empowers researchers to tackle previously intractable problems and unlock new insights into the natural world.

Recent advancements in scientific computing showcase a remarkable ability of novel models to generalize beyond their training data. Studies consistently reveal performance improvements when applying architectures like Fourier Neural Operators (FNO) and Transformers to scenarios with previously unseen physical parameters – a critical capability for real-world applications. This robust out-of-distribution performance isn’t limited to a single model type; both FNO and Transformer-based approaches demonstrate consistent gains across diverse problem settings. The implication is significant: these models aren’t simply memorizing training data, but are learning underlying physical principles, allowing for accurate predictions even when confronted with conditions outside the initial training scope. This adaptability dramatically expands the potential of these techniques to address complex scientific challenges where exhaustive data collection for every conceivable scenario is impractical or impossible.

A significant advancement in scientific computing lies in the increasing data efficiency of novel methodologies. Traditionally, tackling complex problems in fields like climate modeling or materials science demanded vast datasets for training simulations – a substantial obstacle for many researchers. However, techniques leveraging Neural Operators and large-scale foundation models are demonstrably reducing this data burden. These methods effectively learn underlying physical principles from limited observations, allowing for accurate predictions and accelerated discovery with significantly less computational expense. This lowered barrier to entry empowers a broader range of scientists, including those with limited access to extensive resources, to investigate previously intractable problems and contribute to cutting-edge research. The potential for innovation is amplified as data scarcity no longer represents an insurmountable impediment to scientific progress.

The pursuit of efficient learning, as demonstrated in this work regarding neural operators and PDEs, isn’t about accepting limitations-it’s about aggressively testing them. The researchers didn’t simply accept the data demands of traditional methods; they actively challenged the necessity of vast datasets by integrating fundamental physics. This echoes Claude Shannon’s sentiment: “The most important thing is to have a method for transmitting information.” While Shannon spoke of communication channels, the principle applies here: a well-defined ‘channel’ – in this case, the incorporation of physical laws – drastically improves the efficiency of information flow, reducing the ‘noise’ of needing endless data. By establishing these constraints-the physics-the model achieves better generalization and consistency, proving that understanding the underlying rules is paramount to building robust, data-efficient systems.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated gains in data efficiency and generalization, achieved through the injection of fundamental physics, are not surprising-they are, rather, a necessary correction. The prevailing paradigm of simply throwing data at a complex system, hoping for emergent understanding, consistently overlooks the constraints already imposed by reality. This work exposes that approach as fundamentally wasteful, demanding exponentially more data than is strictly required. The true challenge, then, isn’t building bigger networks or collecting more data, but systematically extracting and encoding the underlying rules governing those systems.

However, this isn’t a solved problem. The current approach relies on known physics. What happens when the governing equations are incomplete, or, more likely, entirely unknown? The path forward necessitates developing methods to actively discover those constraints from limited observations – a form of automated reverse-engineering. This demands a shift from passive incorporation of physics to active probing of the system’s boundaries, testing the limits of our assumptions, and embracing the inevitable failures as crucial sources of information.

Ultimately, the long-term success of scientific machine learning hinges not on its ability to mimic intelligence, but on its capacity to rigorously challenge and refine our understanding of the physical world. The pursuit of data efficiency, therefore, is not merely a technical optimization-it’s a philosophical imperative, forcing a confrontation with the limits of our knowledge and the inherent elegance of the universe.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15184.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Overwatch Domina counters

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Honkai: Star Rail Version 4.0 Phase One Character Banners: Who should you pull

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Lana Del Rey and swamp-guide husband Jeremy Dufrene are mobbed by fans as they leave their New York hotel after Fashion Week appearance

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

2026-02-18 21:35