Author: Denis Avetisyan

As artificial intelligence increasingly takes the helm in scientific discovery, ensuring the safe and reliable operation of automated laboratories is paramount.

This review presents Safe-SDL, a framework for establishing safety boundaries and control mechanisms in AI-driven self-driving laboratories using formal verification, operational design domains, and transactional protocols.

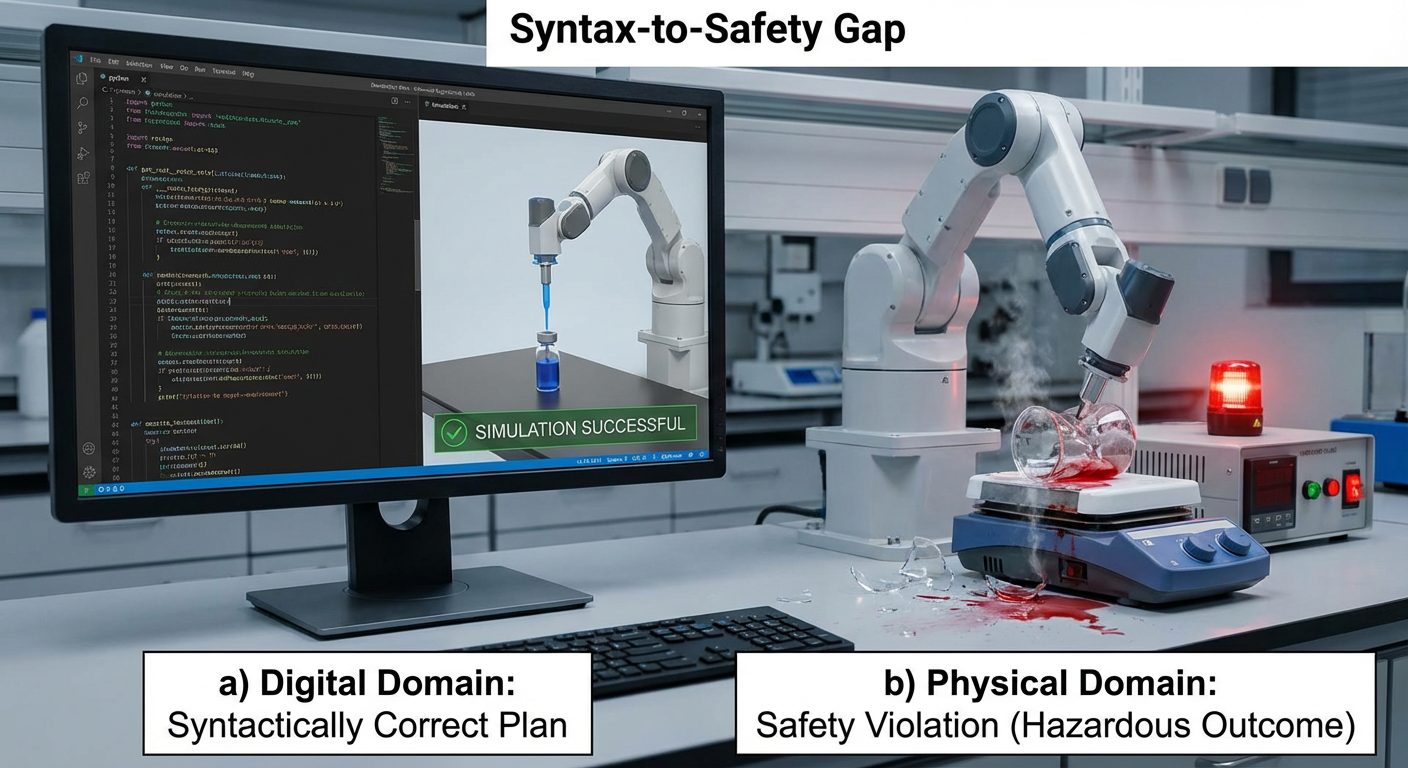

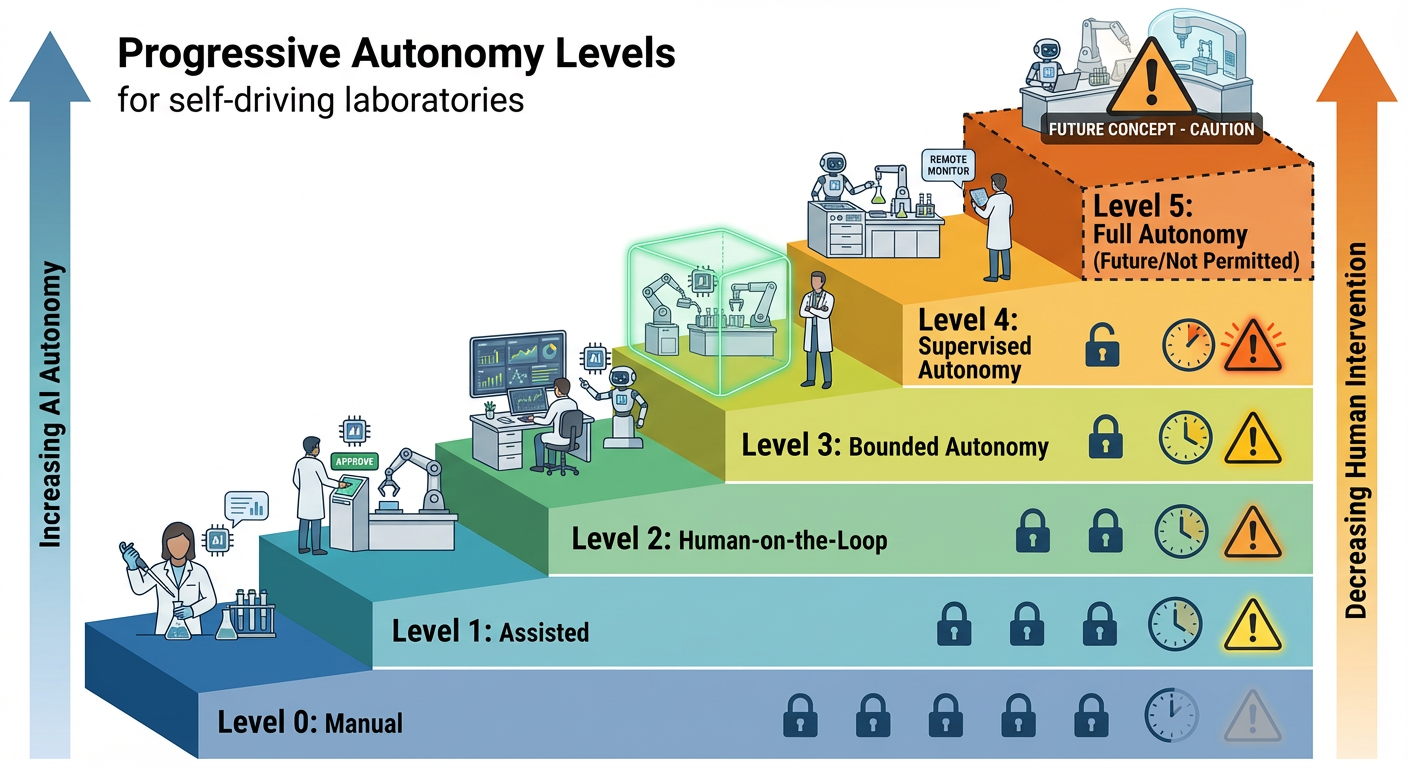

While artificial intelligence promises to accelerate scientific discovery, the deployment of AI-driven Self-Driving Laboratories (SDLs) introduces unique safety challenges beyond those of traditional labs or purely digital systems. This paper presents Safe-SDL: Establishing Safety Boundaries and Control Mechanisms for AI-Driven Self-Driving Laboratories, a comprehensive framework addressing the critical “Syntax-to-Safety Gap” through formally defined Operational Design Domains, Control Barrier Functions, and a novel Transactional Safety Protocol. Our approach establishes a defense-in-depth architecture to guarantee safety in autonomous experimentation, demonstrating that architectural safeguards are essential given the demonstrated failures of foundation models on standard benchmarks. Can these principles pave the way for responsible acceleration of scientific breakthroughs through fully autonomous, yet demonstrably safe, laboratory systems?

Unveiling the Constraints of Conventional Science

Scientific progress, for centuries, has relied on the meticulous efforts of researchers within laboratory settings, a process inherently constrained by both temporal and economic factors. Each experiment requires significant investment – in materials, equipment, and, crucially, researcher time – creating a bottleneck that limits the sheer volume of inquiries that can be pursued. Beyond these practical limitations, the very nature of human investigation introduces potential for bias – preconceived notions, selective observation, and interpretation influenced by existing paradigms can subtly, yet profoundly, shape experimental design and data analysis. This isn’t necessarily a flaw, but a fundamental characteristic of human cognition; however, it does mean that avenues of inquiry potentially holding groundbreaking discoveries may be overlooked, simply because they fall outside established theoretical frameworks or don’t align with prevailing expectations. The inherent slowness and resource demands, combined with the subtle influence of human subjectivity, collectively highlight the need for innovative approaches to accelerate the pace and broaden the scope of scientific exploration.

The confluence of robotics, artificial intelligence, and automation is poised to revolutionize the pace of scientific breakthroughs. By integrating these disciplines, researchers envision laboratories capable of designing and executing experiments with minimal human intervention. This shift promises to overcome limitations inherent in traditional research – namely, the time-consuming nature of manual experimentation, the substantial resource demands, and the potential for unconscious biases influencing data interpretation. Automated systems can tirelessly explore vast experimental spaces, identify subtle patterns often missed by human observation, and accelerate the iterative process of hypothesis formulation and testing. Ultimately, this convergence aims to not simply assist scientists, but to establish a cycle of autonomous discovery, drastically shortening the timeline from initial question to validated answer and unlocking new frontiers in diverse fields like materials science, drug development, and fundamental physics.

The future of scientific advancement hinges on developing systems that can independently formulate and test hypotheses, moving beyond human-directed experimentation. These autonomous systems necessitate an integrated approach, combining data analysis with robotic manipulation to design, execute, and interpret experiments without constant human intervention. Such a capability promises to dramatically accelerate the pace of discovery by circumventing the limitations of manual research – its inherent slowness, substantial resource demands, and susceptibility to unconscious biases. The creation of these systems requires not merely automation of existing protocols, but genuine scientific creativity – the ability to propose novel experiments based on observed data and refine theories based on the resulting evidence, effectively mimicking – and potentially exceeding – the iterative process of human scientific inquiry.

The pursuit of fully autonomous scientific discovery hinges critically on exceeding current limitations in safety and reliability. While artificial intelligence shows promise in automating experimentation, existing models consistently demonstrate performance gaps when subjected to rigorous testing on benchmarks like LabSafetyBench and SOSBENCH. These evaluations reveal vulnerabilities in predicting potentially hazardous outcomes and ensuring procedural correctness – essential attributes for any system operating independently in a laboratory setting. Addressing these shortcomings requires advancements beyond simply improving algorithmic accuracy; it necessitates a fundamental shift towards AI systems capable of robust risk assessment, fail-safe mechanisms, and a demonstrable understanding of experimental constraints, ultimately prioritizing secure and dependable operation above all else.

![A six-year research roadmap details the progression of autonomous laboratory safety from foundational protocols ([years 1-2]), through integrated risk management and formal verification ([years 2-4]), to fully autonomous operation with safety guarantees enabled by advances in hardware, software, and governance ([years 4-6]), addressing key challenges like formal verification scalability, adaptive control barrier functions, and multi-agent coordination.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.15061v1/assets/f8.png)

Deconstructing the Traditional Lab: The Self-Driving Paradigm

The Self-Driving Laboratory signifies a departure from traditional scientific experimentation by integrating automated physical systems with advanced software control. Historically, laboratory processes relied on manual intervention for tasks such as reagent dispensing, data acquisition, and environmental control. These new laboratories utilize robotic platforms and precision instruments directly governed by algorithms, enabling fully autonomous operation. This combination facilitates high-throughput experimentation, minimizes human error, and allows for the exploration of complex parameter spaces inaccessible with conventional methods. The shift is not merely increased automation; it’s a closed-loop system where software directs hardware, analyzes results, and iteratively refines experimental protocols without direct human oversight.

Foundation Models serve as the core intelligence within the Self-Driving Laboratory, enabling both experimental planning and data analysis. These models, typically large neural networks pre-trained on extensive datasets, facilitate the generation of hypotheses, the design of experiments to test those hypotheses, and the subsequent interpretation of collected data. Specifically, they move beyond simple automated execution by providing reasoning capabilities; the models can predict experimental outcomes, identify optimal parameter settings, and autonomously adjust experimental procedures based on observed results. This contrasts with traditional automated systems that require pre-defined scripts, as Foundation Models can generalize to novel situations and adapt to unforeseen data patterns, thereby accelerating the scientific discovery process.

The Operational Design Domain (ODD) constitutes a critical safety component of the Self-Driving Laboratory by specifying the conditions under which the system is designed to function. This domain is not simply a geographical area, but a comprehensive definition encompassing all operational constraints, including environmental factors like weather and lighting, road conditions, traffic patterns, and the types of objects and scenarios the system is equipped to handle. A clearly defined ODD is crucial for establishing system limitations and validating performance; operation outside of the designated ODD requires either fallback mechanisms or human intervention. The robustness of the ODD directly impacts the reliability and safety of the automated experimentation process within the laboratory, as it provides a known and validated space for data collection and model training.

Unlike traditional laboratory automation which typically focuses on isolated task execution, the Self-Driving Laboratory necessitates a fully integrated operating system to manage the complex interplay between hardware and software components. This system must handle real-time data acquisition from multiple instruments, dynamically adjust experimental parameters based on ongoing analysis, and ensure seamless communication between the robotic platform, data storage, and computational resources. Crucially, it requires capabilities beyond simple sequencing; the operating system must facilitate closed-loop experimentation, enabling the laboratory to autonomously refine hypotheses, execute tests, and interpret results without constant human intervention, demanding a unified software architecture for cohesive control and data management.

Formalizing Safety: A Shield Against the Unexpected

Prior to deployment, autonomous laboratories necessitate a comprehensive safety lifecycle beginning with proactive hazard identification and risk assessment. This process involves systematically identifying potential sources of harm – including mechanical, electrical, chemical, and thermal hazards – associated with laboratory equipment, experimental procedures, and environmental factors. Following hazard identification, a detailed risk assessment evaluates the severity of potential consequences and the probability of occurrence for each identified hazard. This assessment informs the implementation of appropriate mitigation strategies, such as engineering controls, administrative procedures, and personal protective equipment, designed to reduce risks to acceptable levels. Documentation of both the hazard identification and risk assessment processes is crucial for regulatory compliance and ongoing safety management.

The Safety Kernel functions as a central component for enforcing safe operational limits within the autonomous laboratory environment. It is architected using Control Barrier Functions (CBFs), which mathematically define safe states and guide the system to maintain them, and Transactional Safety Protocols (TSPs). TSPs ensure that all actions are executed within the bounds defined by the CBFs; a transaction either completes fully and safely, or is rolled back entirely to prevent unsafe intermediate states. This combination provides a robust mechanism for preventing violations of defined safety constraints during experiment execution, even in the presence of disturbances or uncertainties. The kernel monitors all actuators and processes, intervening when a proposed action would lead to an unsafe configuration, effectively acting as a fail-safe layer.

Formal verification of safety-critical autonomous laboratory components utilizes mathematical methods to establish correctness and reliability, moving beyond traditional testing. This process involves creating a formal model of the component’s intended behavior and rigorously proving, using theorem provers or model checkers, that the implementation satisfies the specified safety properties. Specifically, the Safety Kernel, responsible for enforcing operational constraints, undergoes formal verification to guarantee its adherence to defined safety barriers. Verification techniques include specifying properties in temporal logic, such as Linear Temporal Logic (LTL) or Computation Tree Logic (CTL), and then using automated tools to confirm these properties hold true for all possible system states. Successful formal verification provides a high degree of confidence in the absence of runtime errors that could compromise safety, exceeding the coverage achievable through empirical testing alone.

System safety validation utilizes benchmark suites, notably LabSafetyBench, to assess performance under a range of operational conditions. LabSafetyBench provides a standardized set of laboratory scenarios, including variations in equipment configurations, experimental procedures, and potential failure modes. Evaluation metrics focus on constraint satisfaction – verifying the system maintains predefined safety boundaries – and successful completion of tasks without violating safety protocols. Benchmarking against LabSafetyBench allows for quantitative comparison of safety performance across different autonomous laboratory systems and provides a means to identify and address potential vulnerabilities before deployment in real-world settings.

![The Safe-SDL framework employs a defense-in-depth, three-layer hierarchical architecture-cloud-based AI planning, a safety-critical orchestration kernel enforcing constraints like [latex]ODD[/latex] validation and [latex]CBF[/latex] control, and a hardware execution layer via [latex]ROS2[/latex]-with bidirectional data flow and safety gate checkpoints to contain failures.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.15061v1/assets/f1.png)

Beyond Automation: The Long View of Scientific Progress

The capacity for truly long-term, autonomous experimentation represents a paradigm shift in scientific methodology. Traditionally constrained by the need for constant human oversight, research can now extend for weeks or even months without direct intervention. This sustained operation allows for the observation of subtle, long-term effects that might otherwise be missed, and enables iterative experimentation at a scale previously unattainable. By removing the limitations of diurnal cycles and human availability, autonomous labs can continuously refine hypotheses, gather data, and even design follow-up experiments – effectively functioning as perpetually running scientific inquiries. This continuous process promises to dramatically accelerate the pace of discovery, particularly in fields requiring extensive observation or complex, multi-stage processes, and opens avenues for exploring phenomena beyond the temporal constraints of conventional research.

The realization of truly autonomous scientific exploration hinges on dependable, scalable infrastructure, and systems like SafeROS and Osprey are emerging as cornerstones for this endeavor. These platforms move beyond simple scripting to offer robust frameworks – complete with safety certifications like SafeROS – enabling the construction of physical laboratories capable of running experiments with minimal human intervention. Osprey, for instance, provides a complete robotic system, including hardware and software, designed specifically for automated experimentation. Importantly, these aren’t merely research prototypes; they represent production-ready tools, equipped with features for remote monitoring, data logging, and even automated hypothesis generation and testing. This emphasis on reliability and scalability is crucial; it allows researchers to move beyond single, isolated experiments and begin building self-improving scientific workflows that can run continuously, accelerating the pace of discovery in fields ranging from materials science to drug development.

The convergence of autonomous laboratories and artificial intelligence holds immense potential to dramatically shorten the timeline of scientific discovery. Historically, materials science and drug development have been constrained by the speed of human-driven experimentation; each hypothesis requires manual setup, data collection, and analysis, a process that can take months or even years. Now, automated systems capable of running experiments around the clock, and intelligently adapting experimental parameters based on real-time results, are poised to overcome these limitations. This acceleration isn’t simply about doing more experiments, but about conducting smarter experiments, guided by AI algorithms that can identify promising avenues of research and discard unproductive ones. The result is a projected surge in the rate of new material discovery, faster identification of effective drug candidates, and ultimately, a more rapid expansion of the scientific knowledge base.

The envisioned future of scientific discovery centers on a fully integrated, self-improving ecosystem where artificial intelligence and automated systems drive the entire research process. This isn’t merely about accelerating existing methods, but fundamentally reshaping how science is conducted; algorithms will not only analyze data and formulate hypotheses, but also design, execute, and interpret experiments with minimal human intervention. Such a system promises a virtuous cycle of learning – each experiment informs the next, refining models and prioritizing investigations with increasing efficiency. The potential outcome is a scientific enterprise capable of surpassing human limitations in both speed and scale, continuously pushing the boundaries of knowledge and fostering breakthroughs across diverse fields. This automated scientific loop represents a paradigm shift, moving from hypothesis-driven research to one increasingly guided by data-driven discovery and iterative refinement.

![A multi-layered safety architecture successfully prevented a thermal runaway incident in autonomous chemical synthesis by intercepting an AI-generated command for rapid catalyst injection, replanning for a slower, semi-batch addition, and validating a safe temperature trajectory [latex]h(x)<0[/latex] before physical execution.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.15061v1/assets/f7.png)

The pursuit of autonomous systems, as detailed in Safe-SDL, necessitates a continuous challenging of established limits. Every exploit starts with a question, not with intent. Tim Berners-Lee observed this spirit when he stated, “The Web is more a social creation than a technical one.” This sentiment echoes the framework’s emphasis on Operational Design Domains and Control Barrier Functions; defining boundaries isn’t about restriction, but about understanding where the system can explore, and what questions it’s equipped to answer safely. The paper’s defense-in-depth architecture isn’t simply about preventing failures, but about creating a space for controlled experimentation-a digital laboratory where the boundaries themselves are subject to rigorous investigation.

What’s Next?

The architecture detailed within establishes a scaffolding-a formalized defense-around the inherently unpredictable nature of AI-driven experimentation. However, this framework, like all boundaries, defines a space of known unknowns. The true challenge lies not in containing the system within prescribed operational design domains, but in anticipating-and gracefully handling-the inevitable breaches. Formal verification offers a comforting illusion of completeness; the mathematics are sound, yet the real world delights in finding the edges of those very proofs.

Future iterations must move beyond static safety barriers and embrace dynamic resilience. The system should not merely prevent failure, but learn from near-misses and adapt its control mechanisms accordingly. Consider the implications of self-modifying laboratories-systems capable of altering their own safety protocols. This introduces a meta-level of control, but also a heightened risk of emergent behavior. The focus shifts from proving safety to demonstrating robust recovery-a subtle but critical distinction.

Ultimately, Safe-SDL, or its successors, will not eliminate risk. It will redistribute it. The art, then, is not in building an unbreakable box, but in designing a system that can intelligently disassemble itself before it shatters. Chaos is not an enemy, but a mirror of architecture reflecting unseen connections; acknowledging this invites a more honest, and potentially more powerful, approach to autonomous scientific discovery.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15061.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Overwatch Domina counters

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Honkai: Star Rail Version 4.0 Phase One Character Banners: Who should you pull

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- Lana Del Rey and swamp-guide husband Jeremy Dufrene are mobbed by fans as they leave their New York hotel after Fashion Week appearance

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

2026-02-18 15:02