Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new method efficiently reconstructs complex chemical reaction networks directly from experimental data, offering a powerful tool for systems biology.

The framework combines integral System Identification with graph reconstruction for accurate and robust data-driven modeling of mass-action kinetics.

Reconstructing the intricate mechanisms governing chemical reactions from observational data remains a significant challenge in systems biology. This is addressed in ‘Data-driven discovery of chemical reaction networks’, which introduces a novel framework leveraging integral formulations of the Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) method coupled with graph reconstruction techniques. The approach offers improved robustness to noise and enhanced accuracy in both rate-law parameterization and network topology recovery compared to conventional formulations, effectively translating concentration data into mechanistic understanding. Could this advancement pave the way for fully automated, data-driven discovery of complex chemical systems and accelerate innovation in fields like drug discovery and metabolic engineering?

The Inevitable Decay of Models: Reconstructing Chemical Reality

The ability to accurately model chemical reaction networks stands as a cornerstone for advancements across diverse scientific and industrial fields. These models aren’t simply theoretical exercises; they provide a predictive capability essential for optimizing chemical processes, designing novel materials, and even understanding complex biological systems. By mathematically representing the interplay of reactants and products, researchers can simulate reaction outcomes, identify rate-limiting steps, and ultimately enhance efficiency or selectivity. For instance, in industrial catalysis, precise modeling allows for the tailoring of catalysts to maximize yield and minimize waste. Similarly, in atmospheric chemistry, understanding reaction networks is vital for predicting pollutant formation and mitigating environmental impact. The pursuit of more accurate and robust modeling techniques, therefore, directly translates into tangible progress across numerous disciplines, driving innovation and problem-solving capabilities.

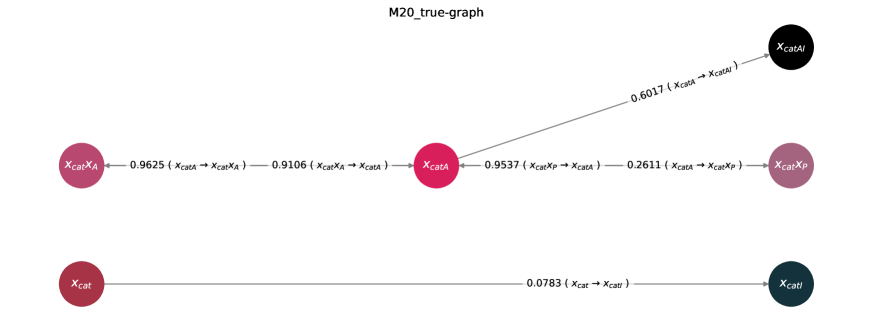

The accurate depiction of chemical reaction networks often falters when confronted with systems exhibiting both reversible and irreversible reactions – a complexity prominently seen in mechanisms like the M20 system, a detailed model of cellular metabolism. Traditional modeling techniques, frequently reliant on assumptions of equilibrium or simplified rate laws, struggle to capture the nuanced interplay between reactions proceeding in both directions and those moving towards completion. This difficulty arises because the balance between forward and reverse rates significantly impacts the system’s dynamic behavior, and an inaccurate representation of even a single reversible step can propagate errors throughout the entire network. Consequently, these approaches may fail to predict realistic concentrations of intermediates or accurately reflect the system’s response to perturbations, highlighting the need for more sophisticated methodologies capable of handling such intricate reaction schemes.

Reconstructing the intricate dance of chemical reactions within a network is profoundly complicated by the unavoidable presence of noise and uncertainty. Experimental data, while essential, is rarely perfect, and inherent limitations in model assumptions introduce further discrepancies between prediction and reality. Current reconstruction methodologies, even sophisticated statistical approaches, often struggle to accurately capture the full dynamic behavior of complex systems under these conditions, leading to incomplete or misleading representations of the underlying chemical processes. This limitation is particularly pronounced when dealing with networks exhibiting both reversible and irreversible reactions, where subtle shifts in reaction rates can drastically alter the overall system dynamics, demanding exceptionally robust and sensitive analytical techniques to achieve reliable results. The pursuit of methods capable of effectively filtering noise and quantifying uncertainty remains a central challenge in systems chemistry.

From Observation to Equation: Identifying Underlying Dynamics

Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDY) is a regression-based technique used to discover governing equations from observed data of ordinary differential equation (ODE) systems. Rather than attempting to identify a single, complex model, SINDY seeks a parsimonious representation by assuming the underlying dynamics can be expressed as a linear combination of a predefined library of candidate functions. This library typically includes nonlinear functions of the state variables, such as polynomials, trigonometric functions, and other relevant terms. A sparsity-promoting regularization technique, such as the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO), is then applied to identify the most significant terms, effectively constructing a simplified model that captures the essential dynamics with fewer parameters. The resulting model takes the general form [latex]\dot{x} = \sum_{i=1}^{N} c_i f_i(x)[/latex], where [latex]x[/latex] represents the state vector, [latex]f_i(x)[/latex] are the candidate functions, and [latex]c_i[/latex] are the coefficients determined through regression.

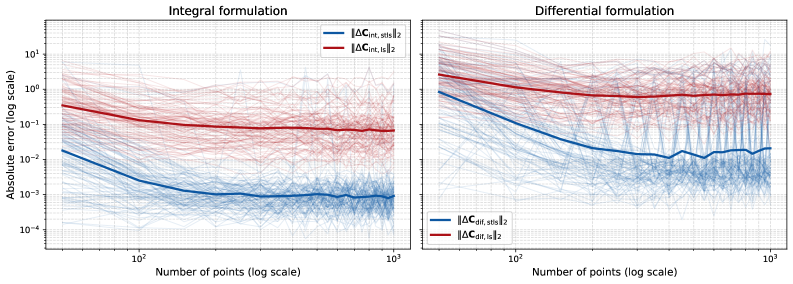

Standard Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDY) methodologies commonly utilize numerical or analytical differentiation to estimate model parameters from time-series data. This derivative-based approach is inherently susceptible to the amplification of observational noise; even small errors in the input data can lead to significant inaccuracies in the calculated derivatives, particularly for higher-order terms or rapidly changing dynamics. Consequently, the resulting identified models may exhibit poor generalization performance and fail to accurately represent the underlying system. This sensitivity necessitates the exploration of alternative formulations that reduce reliance on direct differentiation and improve robustness to noisy measurements.

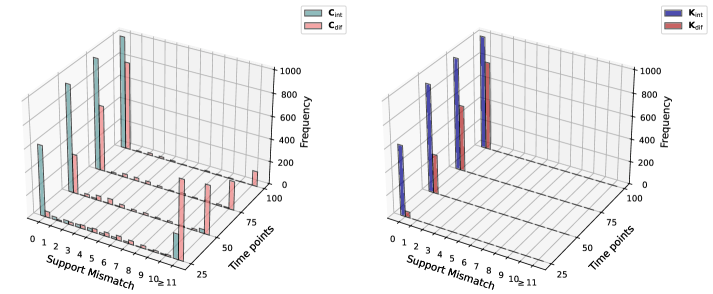

Integral and Differential Formulations offer improved robustness in system identification compared to methods reliant on direct differentiation. These approaches circumvent the noise sensitivity inherent in calculating derivatives by instead estimating model parameters through integral or differential relationships derived from the observed data. Specifically, the integral formulation estimates parameters by minimizing the error between the system’s integral response and the observed integral response, while the Differential Formulation directly estimates parameters from differential relationships. Benchmarking demonstrates that these formulations consistently yield more accurate reconstructions of the underlying system dynamics, particularly in scenarios with noisy or limited data, as they reduce the amplification of measurement errors that plague differentiation-based techniques.

Constraining the Inevitable: Imposing Consistency on Dynamic Reconstructions

The Integral Consistency Penalty improves model robustness by directly addressing inconsistencies arising from numerical integration schemes, specifically those used within Runge-Kutta methods. This is achieved by adding a penalty term to the overall objective function that quantifies the deviation of the learned dynamics from the exact consistency condition of the chosen Runge-Kutta integrator. This penalty forces the model to learn dynamics consistent with the integrator’s properties, thereby reducing sensitivity to noise and uncertainties in the observed data. The result is a learned system that behaves more predictably and accurately, even when input data is imperfect or incomplete, as the penalty effectively constrains the solution space to dynamically feasible trajectories given the integration method.

Efficient computation of the integral terms within the Integral Consistency Penalty is frequently achieved through the use of Implicit Neural Representations (INRs). INRs represent functions as the output of a neural network, allowing for continuous and differentiable function approximation. This is particularly beneficial for evaluating the integrals required by the penalty, as direct numerical integration can be computationally expensive or require a discrete representation of the solution space. By parameterizing the integral as a neural network, INRs enable efficient evaluation at any point and automatic differentiation, simplifying the optimization process and reducing computational costs associated with enforcing the consistency penalty.

Utilizing an Integral Consistency Penalty within integral formulations yields improved accuracy in dynamic reconstruction, particularly in scenarios with limited or noisy data. Empirical results demonstrate consistently lower reconstruction errors when compared to differentiation-based methods; specifically, performance remains superior even when subjected to additive Gaussian noise with a variance of [latex]10^{-4}[/latex]. This robustness stems from the penalty’s ability to constrain the solution space, effectively mitigating the impact of noisy observations and ensuring stable dynamic reconstruction.

![Assuming all species are reactant complexes allows for correct recovery of the underlying chemical reaction network [latex]G[/latex], while failing to do so leads to an inaccurate reconstruction as demonstrated by the incorrect graph obtained when a zero-complex is added.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.11849v1/x18.png)

Beyond Reconstruction: Towards Predictive Resilience in Chemical Modeling

The bedrock of effective chemical engineering relies on the precise depiction of reaction rates, a field governed by Mass-Action Kinetics. This approach, however, requires more than simply defining reaction velocities; it demands adherence to the fundamental principle of mass conservation. The Kirchhoff Matrix emerges as a critical tool in enforcing this balance within complex reaction networks. By ensuring that the total mass of each element remains constant throughout the system, the Kirchhoff Matrix constrains the model, preventing physically unrealistic solutions and bolstering the reliability of simulations. This mathematical framework isn’t merely a computational convenience; it’s essential for accurately predicting the behavior of chemical processes, from optimizing industrial reactors to understanding intricate biochemical pathways, and forms the basis for advanced predictive modeling techniques.

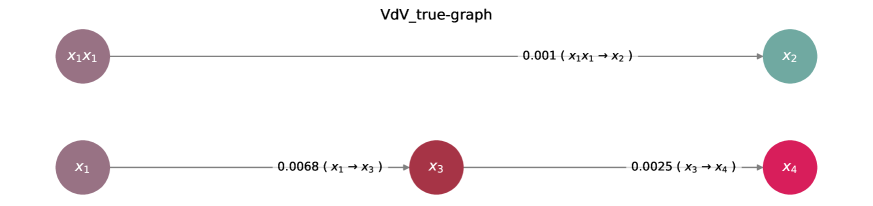

Advanced system identification techniques are proving invaluable in deciphering the intricacies of complex chemical networks, such as the Van de Vusse Reaction. These methods enable accurate reconstruction of these networks – essentially, mapping the relationships between reactants and products – with a notable enhancement in ‘support recovery’. This refers to the model’s ability to correctly identify the key interactions within the network, even when data is limited or noisy. Crucially, the performance of these techniques shines particularly at lower temporal resolutions – meaning when measurements are taken less frequently. This capability is significant because high-frequency data collection can be costly and impractical in many industrial settings; therefore, the ability to build reliable models from sparse data represents a substantial advancement in process understanding and control.

Integrating conservation laws directly into the ordinary differential equation (ODE) system offers a powerful method for refining model accuracy and resilience. This approach transcends traditional system identification by imposing physical constraints – such as mass or energy balance – on the model parameters during the reconstruction process. Consequently, the resulting models exhibit superior performance compared to those derived from differentiation-based methods, particularly in scenarios involving noisy or incomplete data. By ensuring adherence to fundamental physical principles, these constrained models not only achieve more accurate reconstructions of complex chemical reaction networks, like the Van de Vusse reaction, but also demonstrate enhanced robustness and predictive capability, even when faced with limited temporal resolution or significant data uncertainty. This method effectively minimizes the solution space, guiding the model towards physically plausible and reliable parameter estimations.

The pursuit of reconstructing chemical reaction networks from data, as detailed in this work, inherently acknowledges the inevitable accumulation of approximation. Each simplification made in the modeling process – be it through sparse regression or integral formulations of SINDy – introduces a degree of ‘technical debt’ in the system’s memory. As Max Planck observed, “An appeal to the authority of time will never be sufficient.” This resonates with the fact that while the framework presented strives for improved accuracy and robustness, it operates within the constraints of available data and model assumptions. The reconstructed networks, therefore, are not absolute truths, but rather the most probable interpretations given the current information – interpretations that will inevitably evolve as new data emerges and our understanding deepens. The system ages, but the goal is graceful decay – a model that admits its limitations and anticipates future refinement.

What Remains to be Seen?

The reconstruction of chemical reaction networks from data, as presented, represents not an arrival, but a refinement of methodology. Every delay in achieving a complete, predictive model is, in effect, the price of deeper understanding. The current framework addresses significant limitations of prior approaches, yet relies, inherently, on the assumption that the underlying system is amenable to sparse representation. The true complexity of biochemical systems-the myriad of transient interactions, the influence of spatial heterogeneity, the subtle interplay of regulatory mechanisms-suggests this assumption, while often useful, is ultimately a simplification.

Future work must confront the limitations imposed by data scarcity and noise. Architecture without historical context-without acknowledgement of the inherent uncertainty-is fragile and ephemeral. Developing methods for quantifying model uncertainty, for incorporating prior knowledge in a rigorous fashion, and for effectively leveraging multi-scale data will be crucial.

Ultimately, the success of data-driven modeling will not be measured by the fidelity with which models reproduce known networks, but by their ability to predict novel phenomena and to guide the design of systems that do not yet exist. The true test lies not in mirroring the past, but in anticipating the inevitable decay of the present and, perhaps, shaping the future.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11849.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Honkai: Star Rail Version 4.0 Phase One Character Banners: Who should you pull

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- Top 10 Super Bowl Commercials of 2026: Ranked and Reviewed

- Gold Rate Forecast

- ‘Reacher’s Pile of Source Material Presents a Strange Problem

- Lana Del Rey and swamp-guide husband Jeremy Dufrene are mobbed by fans as they leave their New York hotel after Fashion Week appearance

- Meme Coins Drama: February Week 2 You Won’t Believe

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Olivia Dean says ‘I’m a granddaughter of an immigrant’ and insists ‘those people deserve to be celebrated’ in impassioned speech as she wins Best New Artist at 2026 Grammys

2026-02-14 08:15