Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach allows robots to learn complex tasks by understanding and anticipating the movements humans make during demonstrations.

Modeling human preferences through visual motion prediction significantly improves robot skill acquisition from egocentric video data.

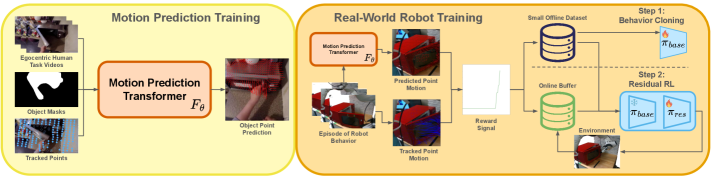

Learning complex skills remains a challenge for robots, particularly when relying on demonstrations as a source of guidance. This paper, ‘Human Preference Modeling Using Visual Motion Prediction Improves Robot Skill Learning from Egocentric Human Video’, introduces a novel approach to reward function design by modeling human preferences through prediction of object motion in egocentric videos. This allows robots to learn more effectively from human demonstrations by aligning with intuitive human expectations of desired behavior, outperforming prior methods in both simulation and real-world robotic tasks. Could this motion-based preference modeling serve as a generalizable framework for bridging the gap between human intention and robotic action?

The Illusion of Intelligent Machines: Bridging the Gap Between Simulation and Reality

Conventional approaches to robot learning frequently demand substantial upfront investment in either carefully designed reward functions or lengthy human-guided demonstrations. The creation of effective reward signals requires significant engineering expertise to accurately define desired behaviors, a process that can be both time-consuming and prone to unintended consequences as robots may exploit loopholes in the reward structure. Alternatively, relying on teleoperation-where a human directly controls the robot to generate training data-is similarly restrictive, scaling poorly with task complexity and limiting the robot’s ability to generalize beyond the demonstrated examples. Both methods present considerable bottlenecks, hindering the development of adaptable and truly autonomous robotic systems capable of operating effectively in unstructured environments.

The transfer of robotic policies from simulated environments to the physical world is frequently hindered by what researchers term the ‘reality gap’. This disparity arises from fundamental differences between the idealized conditions of simulation and the complexities of real-world physics and sensor data. Simulations, while computationally efficient, often fail to fully capture nuances like friction, unpredictable lighting, or the subtle give of materials, leading to policies that perform well virtually but falter when deployed on a physical robot. Even minor discrepancies in these dynamics can accumulate, causing significant performance degradation; a robot trained to grasp an object in a pristine simulation may struggle, or even fail, when confronted with a slightly worn or irregularly shaped object in a real-world setting. Bridging this gap necessitates developing techniques that account for these imperfections, either through more sophisticated simulation, robust policy adaptation, or methods that allow robots to learn and generalize directly from limited real-world experience.

Capturing the nuances of human preference for robotic tasks proves remarkably difficult, extending beyond merely replicating observed actions. Current approaches often treat demonstrations as direct blueprints, failing to discern the intent behind those actions – the underlying goals a human seeks to achieve. This limitation hinders a robot’s ability to adapt to novel situations or efficiently learn from limited data; a robot mimicking a specific path to stack blocks, for example, doesn’t necessarily understand the broader objective of creating a stable structure. Consequently, research is shifting towards methods that infer these higher-level goals – leveraging techniques like inverse reinforcement learning and preference-based learning – allowing robots to not just what humans do, but why they do it, ultimately leading to more robust and intuitive human-robot collaboration.

From Hand-Crafted Rewards to Learned Intentions: A More Pragmatic Approach

The proposed framework enables reward signal acquisition directly from human video data, eliminating the requirements for manually designed reward functions or extensive task demonstrations. This is achieved by training a model to observe human actions within video sequences and infer the underlying reward structure implicit in those actions. By learning directly from visual input, the system can generalize to new situations without explicit reprogramming of reward criteria, offering a more adaptable and scalable approach to reinforcement learning compared to traditional methods reliant on predefined reward signals or detailed trajectory data.

The system infers task goals from visual inputs by utilizing Value Implicit Pretraining (VIP) and pretrained foundation models, specifically RoboReward. VIP enables the model to learn a value function that predicts the expected cumulative reward from a given state without explicit reward signals. RoboReward, a pretrained model, provides a strong prior for understanding robotic tasks and generalizes to new environments. By combining VIP with RoboReward, the system can effectively learn from unlabeled video data, extracting implicit reward signals from human demonstrations and inferring the underlying goals of the observed actions. This approach bypasses the need for manually defining reward functions or collecting extensive, labeled datasets.

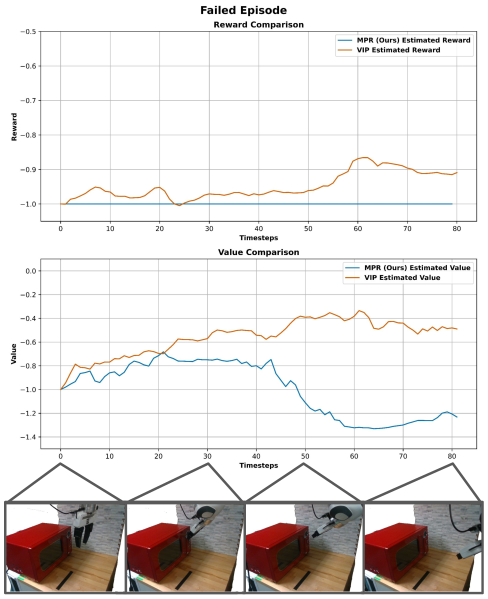

The system estimates reward signals by predicting the long-term cumulative value of observed states. This prediction is refined by incorporating information regarding the temporal distance to goal frames within the video; states closer to the completion of a task are assigned higher values. This temporal weighting allows the model to differentiate between states that are immediately beneficial and those that contribute to eventual success, enabling it to more accurately capture nuanced human preferences as demonstrated in the visual data. The predicted values are used as a proxy for human-defined rewards, eliminating the need for explicit reward function design.

Seeing is Believing: Tracking Motion in a Dynamic World

Accurate prediction of object motion is fundamental to task planning and reinforcement learning, as it enables agents to anticipate future states and optimize actions for desired outcomes. To estimate object movement, systems utilize techniques such as point tracking, which involves identifying and following salient points on an object across successive video frames. By continuously monitoring the position of these points, the system can calculate velocity, acceleration, and trajectory, providing a predictive model of the object’s future location. This motion estimation is then used to inform reward signal generation; for example, anticipating successful task completion based on predicted object interactions allows for more effective learning and policy optimization.

CoTracker3 is a multi-object tracking algorithm designed to maintain object identities across video frames, even in visually complex environments. It achieves this by formulating tracking as a global data association problem solved with a Many-to-One assignment algorithm. This approach allows CoTracker3 to effectively handle occlusions and maintain track consistency by associating detections in the current frame with existing tracks based on appearance and motion features. The algorithm’s robustness in cluttered scenes stems from its ability to leverage contextual information and avoid identity switches, a common challenge in multi-object tracking systems.

The integration of visual encoders, specifically DinoV2, into motion prediction and reward estimation pipelines improves performance by generating robust feature representations from video data. DinoV2, a self-supervised vision transformer, is pre-trained on extensive datasets to learn discriminative visual features without requiring labeled data. These features, extracted from each video frame, capture essential information about object appearance and context, enabling more accurate prediction of object trajectories and, consequently, more reliable estimation of reward signals. The use of pre-trained models like DinoV2 reduces the need for extensive task-specific training data and improves generalization to novel environments and scenarios, as the encoder has already learned a strong prior about visual structure.

From Benchmarks to Reality: Validating the Approach

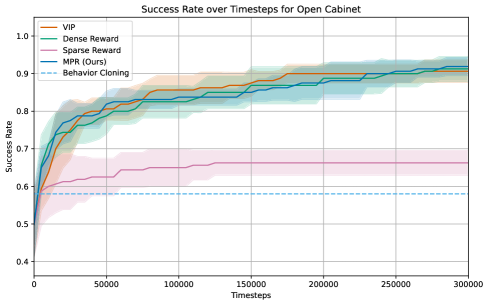

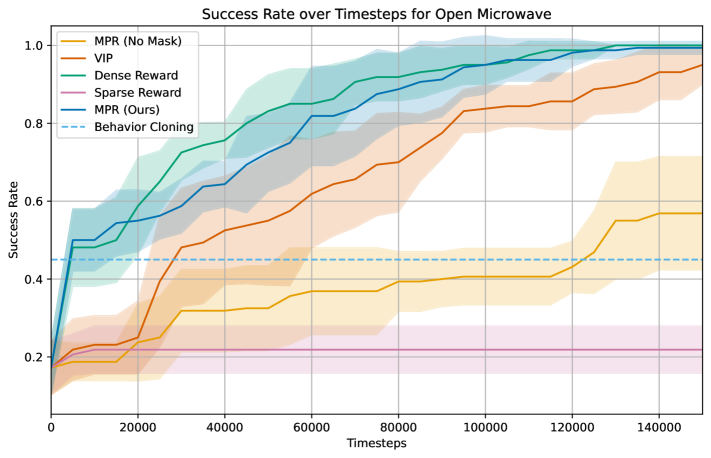

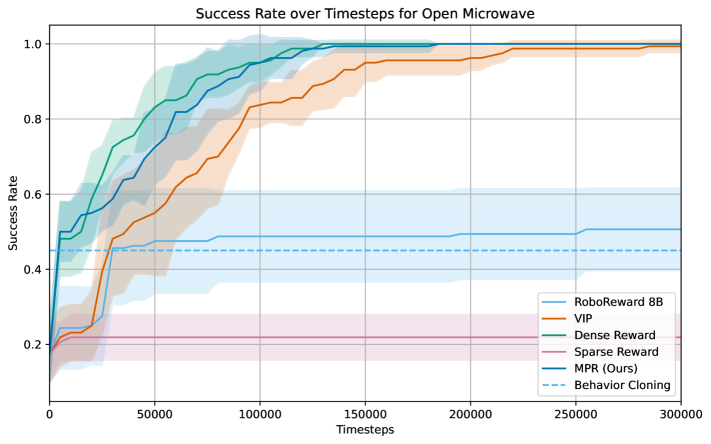

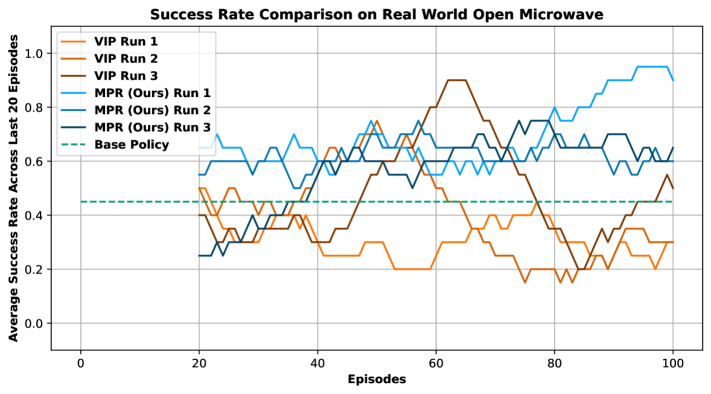

The efficacy of this robotic framework was rigorously tested using the Franka Kitchen Benchmark, a challenging suite of tasks designed to assess real-world manipulation capabilities. Performance was evaluated across common household activities, including the nuanced motions required to safely open a microwave, meticulously wipe a kitchen counter, and accurately fold a cloth. This benchmark provided a standardized environment for quantifying improvements in robotic skill, allowing for direct comparison against existing methods in behavior cloning and reinforcement learning. Success wasn’t simply measured by task completion, but by the robot’s ability to execute these actions with the dexterity and reliability expected in a domestic setting, paving the way for more adaptable and helpful robotic assistants.

The research highlights a significant advancement in robotic learning through the implementation of learned reward models. Traditional methods, such as behavior cloning – where robots directly imitate demonstrated actions – and reinforcement learning – which relies on trial-and-error to maximize rewards – often struggle with the complexities of real-world tasks. This work demonstrates that by first learning a reward model, robots can more effectively generalize to new situations and achieve higher success rates. This approach allows the robot to understand why an action is good, rather than simply what action to take, leading to more robust and adaptable performance in complex environments like a typical kitchen setting.

Evaluations on the Franka Kitchen Benchmark reveal significant gains in robotic task completion through the implementation of a novel Motion Prediction Reward (MPR) method. This approach demonstrably elevates performance in complex household activities; specifically, success rates increased by 31.7% when opening a microwave and 28.3% when folding a cloth, indicating a substantial advancement over conventional behavior cloning and reinforcement learning techniques. Notably, the system achieved a 76.7% success rate in opening the microwave, highlighting its potential for reliable real-world application and suggesting a pathway toward more capable and adaptable robotic assistants.

Scaling to Complexity: The Future of Adaptive Robotics

Current advancements in robotic learning are poised to move beyond controlled laboratory settings and tackle the challenges of real-world complexity. Researchers are increasingly turning to large-scale datasets, such as Ego4D and Epic Kitchens, which capture the nuanced and often unpredictable nature of everyday human activities. These datasets, comprising hours of first-person video and detailed annotations, provide the necessary breadth of experience for robots to learn robust and generalizable skills. By training on this data, robots can develop a better understanding of object interactions, human intentions, and the inherent messiness of unstructured environments – ultimately enabling them to operate more effectively in dynamic and unpredictable settings like homes and offices. This scaling up of data and complexity represents a crucial step towards creating truly adaptive and helpful robots.

Residual reinforcement learning presents a powerful pathway towards creating truly personalized robotic assistants. This approach doesn’t require robots to relearn skills from scratch when encountering new users or slightly different environments; instead, it builds upon pre-existing, broadly trained policies. By focusing on learning the residual – the difference between the current performance and the desired outcome – robots can efficiently adapt to individual preferences and nuances. Imagine a robotic chef learning a user’s preferred level of seasoning, or a robotic assistant mastering a unique way of organizing a workspace; this fine-tuning happens much faster and with less data than full policy retraining. The technique allows for a continuous learning loop, enabling robots to refine their behaviors over time and become increasingly attuned to the specific needs of those they serve, ultimately bridging the gap between generalized robotic competence and truly helpful, personalized assistance.

The development of truly useful robotics hinges on creating machines capable of fluid interaction within the complexities of human life. This necessitates a shift from robots executing pre-programmed instructions to systems that learn continuously from observation and adapt to dynamic circumstances. Researchers envision robots not merely performing isolated tasks, but seamlessly integrating into daily routines, anticipating needs, and offering assistance across a broad spectrum of activities. Such robots would leverage observational learning to understand human intentions and preferences, allowing for personalized interaction and efficient task completion, ultimately becoming intuitive and reliable partners in both domestic and professional settings.

The pursuit of elegant reward signals, as demonstrated in this work on preference modeling, invariably encounters the realities of deployment. This paper attempts to distill human intention through motion prediction – a clever approach, yet one bound by the inherent messiness of real-world data. It echoes a familiar truth: everything optimized will one day be optimized back. The researchers believe predicting object motion enhances robot skill learning, but production will always find a way to break elegant theories. As Edsger W. Dijkstra observed, “Simplicity is prerequisite for reliability.” This paper’s contribution lies not in a perfect solution, but in a carefully considered compromise that survived the initial phases of testing-a testament to pragmatic design in the face of intractable complexity.

What’s Next?

This work, predictably, sidesteps the messy reality of deployment. Modeling human preference through motion prediction is elegant, certainly. But anyone who’s spent more than five minutes with a robot knows that ‘elegant’ and ‘functional’ are rarely acquainted. The system currently operates on curated video; the moment it encounters a slightly unpredictable human – and they always are – the predicted motions will drift, and the carefully learned reward signal will become… optimistic, at best. It’s a beautiful system, primed to fail consistently – and that, at least, is predictable.

The real challenge isn’t better prediction, it’s robust degradation. Future iterations will inevitably involve attempts to quantify ‘human error’ – a concept that’s both deeply philosophical and profoundly unhelpful. The field chases ‘generalization’, but the truth is, we don’t write code – we leave notes for digital archaeologists. They’ll eventually discover that every ‘cloud-native’ solution is just the same mess, just more expensive to maintain.

The next logical step, of course, will be incorporating more modalities – sound, haptic feedback, perhaps even subtle shifts in human gaze. Each added layer will increase complexity exponentially, and the inevitable failure modes will become correspondingly more creative. But that’s progress, isn’t it? Or at least, it’s something to document before the system inevitably crashes.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11393.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- Top 10 Super Bowl Commercials of 2026: Ranked and Reviewed

- ‘Reacher’s Pile of Source Material Presents a Strange Problem

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Meme Coins Drama: February Week 2 You Won’t Believe

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Olivia Dean says ‘I’m a granddaughter of an immigrant’ and insists ‘those people deserve to be celebrated’ in impassioned speech as she wins Best New Artist at 2026 Grammys

- Why Andy Samberg Thought His 2026 Super Bowl Debut Was Perfect After “Avoiding It For A While”

- February 12 Update Patch Notes

2026-02-13 20:38