Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a reinforcement learning system that allows two quadruped robots to collaboratively perform complex jumping maneuvers, pushing the limits of robotic teamwork.

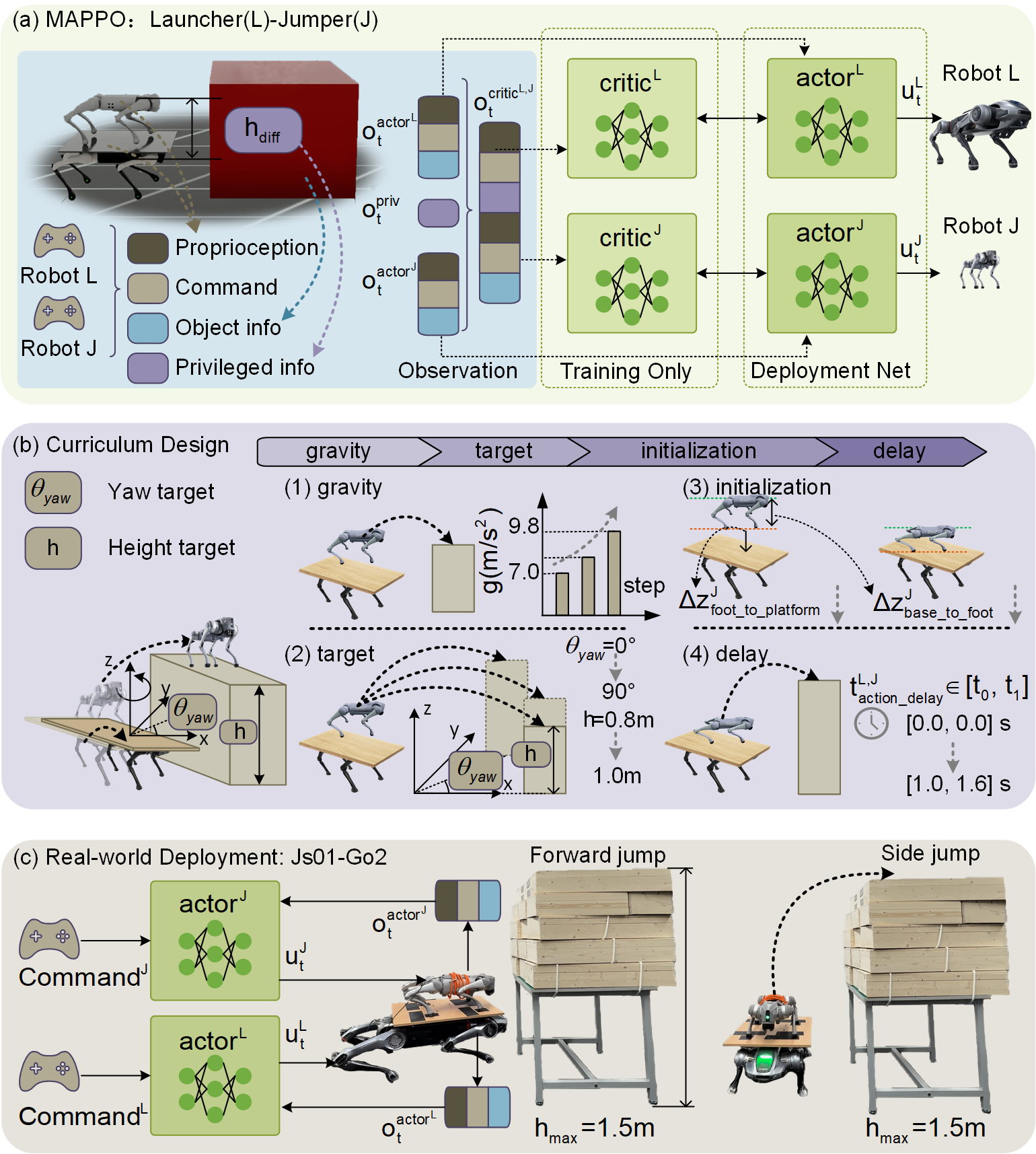

This work demonstrates successful sim-to-real transfer of a multi-agent reinforcement learning framework for cooperative locomotion in quadruped robots using curriculum learning and centralized training with decentralized execution.

While individual quadrupedal robots are fundamentally limited by their physical capabilities, coordinated teamwork offers a pathway to surpass these constraints. This is explored in ‘Co-jump: Cooperative Jumping with Quadrupedal Robots via Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning’, which introduces a framework enabling two robots to collaboratively perform jumps exceeding the height achievable by either alone. By leveraging a progressive curriculum and decentralized execution within a multi-agent reinforcement learning paradigm, the authors demonstrate successful sim-to-real transfer and achieve jumps onto platforms up to 1.5m high-a 144% improvement over standalone performance. Could this approach unlock new possibilities for collaborative locomotion in complex and constrained environments, paving the way for more versatile and capable robotic systems?

The Inevitable Shift: Beyond Individual Robotic Limits

For decades, robotic development prioritized enhancing the capabilities of single, autonomous machines – focusing on improvements in areas like speed, strength, and sensor accuracy. This individual-centric approach, while yielding impressive results in isolated tasks, often overlooked a fundamental principle observed throughout the natural world: the power of collaboration. The limitations of a single robot – be it restricted movement, insufficient lifting capacity, or limited sensing range – can be overcome by strategically coordinating the actions of multiple agents. This shift towards cooperative robotics recognizes that complex challenges frequently demand a synergistic approach, where the combined capabilities of a team surpass those of any individual machine, opening new possibilities for tackling intricate tasks in dynamic and unpredictable environments.

Many real-world challenges demand capabilities that surpass the inherent limitations of a solitary robotic system. A single robot may lack the necessary strength, reach, or dexterity to manipulate complex environments or overcome substantial obstacles. Consequently, researchers are increasingly focused on distributed robotic systems where multiple agents collaborate to achieve a common goal. This paradigm shift acknowledges that synergistic interactions – combining the strengths of individual robots while mitigating their weaknesses – unlock solutions previously inaccessible. For instance, a task requiring both precise manipulation and significant lifting capacity becomes feasible when divided between a robot specializing in dexterity and one designed for heavy loads, demonstrating how collective robotic effort extends the boundaries of what’s physically possible.

A challenging cooperative jumping task was developed as a means to rigorously test and refine synergistic behaviors in multi-robot systems. This benchmark requires robots to coordinate their actions to achieve a collective jump height exceeding the capability of any single unit; real-world experiments demonstrated a maximum jump height of 1.5 meters. The task’s inherent complexity-necessitating precise timing, force distribution, and dynamic balancing-provides a valuable platform for advancing research in areas such as distributed control, motion planning, and inter-agent communication. Successful completion highlights the potential of cooperative robotics to overcome individual limitations and accomplish tasks previously considered unattainable for single robots, opening doors to applications in challenging terrains and complex environments.

Successfully coordinating multiple robots demands control and planning strategies far exceeding those used for single agents. These systems must account for the complex interplay of forces, velocities, and positions between each robot, a challenge amplified by the inherent uncertainties in real-world environments. Researchers are developing algorithms that predict and compensate for these inter-agent dynamics, enabling robots to anticipate each other’s movements and maintain stable, coordinated actions. This often involves modeling the combined system as a single, higher-dimensional entity, or employing decentralized control schemes where each robot adjusts its behavior based on local observations and communicated intentions. Ultimately, robust cooperative behavior hinges on the ability to not just plan individual trajectories, but to dynamically adjust those plans in response to the evolving interactions between agents, fostering a synergistic performance unattainable by solitary robots.

![Simulation demonstrates that a progressively learned curriculum enables the robot to successfully jump onto a [latex]1.5 \,\mathrm{m}[/latex] platform using both forward and side maneuvers, as evidenced by distinct clusters in the UMAP embedding of its learned joint command sequences.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.10514v1/picture/sim_exp/sim_traj_umap2.png)

A Phased Approach: Guiding Robots Towards Collaboration

Curriculum learning was implemented to facilitate the training of quadruped robots in cooperative jumping tasks. This approach involves sequentially presenting the learning agent with easier tasks before progressing to more complex ones, improving sample efficiency and stability. Instead of directly training on the full cooperative jumping task, the robots are initially trained on simpler sub-components, allowing them to develop foundational skills before tackling the combined challenge. This systematic progression is designed to guide the learning process and avoid premature convergence on suboptimal policies, ultimately leading to more robust and generalizable behavior.

The ‘Gravity Curriculum’ serves as the initial training phase, intentionally simplifying the task to accelerate learning and improve the reliability of the reward signal. This is achieved by reducing the gravitational force experienced by the simulated robots. Lowering gravity effectively increases jump height and duration, providing more time for the robots to coordinate and execute the jump. This reduction in task complexity allows the agents to more readily discover successful behaviors and receive positive reinforcement, establishing a strong baseline for subsequent, more challenging curricula. The increased clarity of the reward signal during this phase mitigates the effects of sparse rewards, a common obstacle in reinforcement learning, and ensures robust learning before introducing complexities related to timing and precise coordination.

The Initialization and Delay Curricula are sequential training stages designed to mitigate the effects of discrepancies between the simulated and real-world environments. The Initialization Curriculum focuses on randomizing the initial poses of the robots at the start of each jump attempt, forcing the learning algorithm to develop robust control strategies independent of precise starting conditions. Following this, the Delay Curriculum introduces variable delays in the execution of the jump command, addressing timing inconsistencies that arise from differences in computational speeds and physical response times between simulation and the robot’s hardware. By systematically varying both initial conditions and command timing, the learning agents are trained to be less sensitive to these real-world imperfections, improving transferability and overall performance.

The ‘Target Curriculum’ represents the final phase of training, designed to improve the robots’ ability to generalize jumping skills to a wider range of target locations. Following successful completion of preceding curricula, robots are exposed to increasingly varied target positions, expanding beyond initial, simplified scenarios. This broadened scope of jump targets directly correlates with a measured success rate of 91.69% when attempting jumps to a height of 0.9 meters, demonstrating the effectiveness of the phased approach in achieving robust and adaptable cooperative jumping behavior.

The Inevitable Gap: Bridging Simulation and Reality

The successful deployment of a cooperative jumping policy learned in simulation is hindered by the ‘sim-to-real’ transfer gap, which arises from discrepancies between the simulated environment and the complexities of the physical world. This gap manifests as performance degradation when the policy is applied to real robots due to unmodeled dynamics, sensor noise, and variations in physical parameters. Bridging this gap is essential for realizing the potential of simulation-based reinforcement learning in robotics, and requires techniques to improve the policy’s generalization capability and robustness to real-world uncertainties. Without addressing this transfer gap, policies trained solely in simulation often fail to perform reliably when deployed on physical robot systems.

Domain randomization is employed as a technique to improve the generalization capability of policies learned in simulation by introducing variability in simulation parameters. This involves randomly altering physical properties such as mass, friction coefficients, and actuator strengths, as well as visual characteristics like textures and lighting conditions, during training. By exposing the learning agent to a wide range of simulated environments, the resulting policy becomes more robust to the inevitable discrepancies between the simulation and the real world, reducing the impact of unmodeled dynamics and sensor noise. This approach effectively expands the training distribution to encompass a broader range of potential real-world scenarios, thereby improving the likelihood of successful transfer and performance.

While Domain Randomization improves sim-to-real transfer, discrepancies in actuator performance and contact physics continue to pose substantial challenges. Actuation constraints manifest as differences between simulated motor torque and achievable real-world torque, leading to control errors. Contact friction, similarly, deviates between simulation and reality due to unmodeled surface properties and dynamic effects, impacting the accuracy of force estimations and the stability of contact interactions. These discrepancies necessitate further refinement of simulation fidelity or the implementation of robust control strategies capable of mitigating the effects of these persistent modeling errors.

Successful cooperative jumping relies significantly on accurate proprioceptive feedback – data concerning the robots’ joint angles, velocities, and body pose – for both state estimation and closed-loop control. This internal sensing provides the necessary information for the robots to understand their own configuration and adapt to dynamic changes during the jump sequence. Experiments demonstrate that utilizing accurate proprioceptive data enables a 92.83% success rate in achieving a target jump height of 1.2 meters. Inaccurate or delayed proprioceptive feedback directly degrades performance, hindering the robots’ ability to coordinate and maintain stability throughout the maneuver.

![Real-world experiments demonstrate the robot's ability to perform jumping maneuvers with variable heights ([latex]0.9-1.2[/latex] m) and heading angles ([latex]0^{\circ}[/latex] and [latex]90^{\circ}[/latex]).](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.10514v1/picture/real_exp/real_exp_results.png)

Beyond Individual Capacity: A Future Forged in Collaboration

The demonstrated robotic collaboration highlights a fundamental shift in capability: the ability to surpass the inherent limitations of single robots. Through coordinated action, these agents achieve feats impossible for either operating independently, as exemplified by the successful ‘Co-jump’ task. This isn’t merely about combining strengths; it’s about leveraging complementary skills and distributing the demands of a complex operation. The Launcher robot, with its powerful [latex]270 N\cdot m[/latex] calf joint torque, effectively provides the initial impetus, while the Jumper robot, generating [latex]40 N\cdot m[/latex] of force, refines the trajectory and landing. This synergistic approach establishes a powerful precedent, suggesting that future robotic systems will increasingly prioritize collaboration as a means of tackling previously insurmountable challenges and unlocking new possibilities in fields ranging from search and rescue to space exploration.

The ‘Co-jump’ task, designed to assess collaborative robotic performance, provides a standardized and repeatable method for evaluating and comparing the effectiveness of various cooperative control algorithms. This benchmark challenges robots to coordinate actions – specifically, a launch and subsequent jump – demanding precise timing and force distribution between agents. By quantifying success rates and measuring key performance indicators like jump height and stability, researchers can objectively assess the strengths and weaknesses of different control strategies. The task’s inherent complexity, requiring both ballistic calculations and dynamic adjustments based on partner robot behavior, makes it a particularly robust testbed for advancing the field of multi-robot cooperation and pushing the boundaries of what is achievable through coordinated action.

A significant disparity existed in the physical demands placed upon each robot; the Launcher, designated Js01, experienced a peak calf joint torque of 270 N⋅m during the initial propulsion phase. This substantial force indicates the Launcher bore the brunt of overcoming inertia and initiating the jump. Conversely, the Jumper robot, Go2, generated a comparatively modest peak torque of 40 N⋅m, suggesting its primary role was stabilization and trajectory adjustment once airborne. This torque differential highlights the efficiency of the cooperative strategy, distributing the workload and allowing each robot to specialize in the tasks for which it is best suited – a division of labor crucial for tackling more complex challenges.

Investigations are now shifting toward extending this cooperative robotic framework to scenarios demanding greater adaptability and intricacy. Current efforts prioritize the development of algorithms capable of navigating unstructured environments, such as disaster zones or agricultural fields, where dynamic obstacles and unpredictable terrain pose significant challenges. Researchers are also exploring methods to increase the number of collaborating robots within a single system, aiming to enhance overall task efficiency and robustness. A key component of this scaling process involves refining communication protocols and developing decentralized control strategies, allowing robots to coordinate effectively without relying on a central processing unit. Ultimately, this research seeks to move beyond controlled laboratory settings and demonstrate the practical viability of multi-robot collaboration in real-world applications, potentially revolutionizing fields like construction, search and rescue, and environmental monitoring.

The potential of robotic collaboration extends far beyond current capabilities, suggesting a future where complex challenges are routinely addressed through synergistic machine efforts. This vision isn’t simply about automating existing tasks, but about enabling solutions previously considered impossible for a single robot, regardless of its sophistication. Imagine automated disaster response teams navigating rubble fields with coordinated precision, or collaborative construction projects assembling structures with unprecedented speed and accuracy. Such scenarios depend on robots functioning not as isolated units, but as interconnected components of a larger, intelligent system, sharing information, coordinating movements, and collectively overcoming obstacles. This seamless integration promises to unlock new frontiers in exploration, manufacturing, healthcare, and beyond, fundamentally reshaping how humans interact with and benefit from robotic technology.

The pursuit of cooperative locomotion, as demonstrated by this work on quadrupedal robots, reveals a fundamental truth about complex systems. It isn’t simply about programming individual agents to perform tasks, but cultivating an environment where emergent behaviors can flourish. The researchers’ success with sim-to-real transfer highlights that anticipating every possible scenario is futile; instead, a robust system must reveal its weaknesses through interaction with the world. As Edsger W. Dijkstra observed, “It’s not enough to do your best; you must do your best with the best tools.” This research doesn’t present a finished solution, but a fertile ground for future revelations in the art of building resilient, collaborative machines. The curriculum learning approach acknowledges that true resilience begins where certainty ends – and that’s precisely where the most fascinating discoveries lie.

What Lies Beyond the Jump?

This work, focused on cooperative leaping, reveals less about controlling robots and more about the inevitability of emergent behavior. Every dependency – each line of code dictating a robot’s response – is a promise made to the past, a constraint on future adaptation. The successful transfer from simulation to reality is not a victory over physics, but a temporary alignment with it. The real challenge isn’t teaching robots how to jump together, but accepting they will eventually devise methods unforeseen by their creators.

The current framework, while demonstrating impressive coordination, remains tethered to a pre-defined task. A true ecosystem of robotic agents won’t be given problems to solve; it will discover them. The next iteration won’t focus on refining the jump, but on allowing the robots to define what constitutes a jump, or indeed, any coordinated action. This requires relinquishing the illusion of control, acknowledging that robust systems aren’t built, they’re grown – and often, they grow in directions unanticipated.

One suspects the robots, left to their own devices, will eventually begin to fix themselves. The imperfections in hardware, the unpredictable dynamics of the real world – these aren’t bugs to be eliminated, but the very seeds of innovation. Systems, after all, exist in cycles. The jump is merely a fleeting moment in a longer, more complex dance of adaptation and evolution.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.10514.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Married At First Sight’s worst-kept secret revealed! Brook Crompton exposed as bride at centre of explosive ex-lover scandal and pregnancy bombshell

- Top 10 Super Bowl Commercials of 2026: Ranked and Reviewed

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Why Andy Samberg Thought His 2026 Super Bowl Debut Was Perfect After “Avoiding It For A While”

- Influencer known as the ‘Human Barbie’ is dug up from HER GRAVE amid investigation into shock death at 31

- How Everybody Loves Raymond’s ‘Bad Moon Rising’ Changed Sitcoms 25 Years Ago

- Genshin Impact Zibai Build Guide: Kits, best Team comps, weapons and artifacts explained

- Meme Coins Drama: February Week 2 You Won’t Believe

- Brent Oil Forecast

2026-02-12 12:34