Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging the power of generative models to create more accurate and data-efficient simulations of complex physical systems.

This review details a Conditional Denoising Model that implicitly learns the geometry of solution manifolds, improving upon traditional physics-informed machine learning techniques.

Balancing data fidelity with physical consistency remains a central challenge in surrogate modeling of complex systems. This is addressed in our work, ‘Conditional Denoising Model as a Physical Surrogate Model’, which introduces a generative approach learning the intrinsic geometry of the solution manifold itself. By training a conditional denoising model to reconstruct clean states from noisy inputs, we achieve improved parameter and data efficiency, alongside stricter adherence to underlying physical constraints-even without explicit physics-based loss functions. Could this implicit regularization offered by manifold learning unlock a new paradigm for scientific machine learning and physics-informed modeling?

The Challenge of Modeling Complex Systems

High-fidelity kinetic simulations, exemplified by tools like LoKI, meticulously model the intricate interactions within complex systems to generate remarkably accurate data. However, this precision comes at a substantial cost: computational expense. Each simulation demands significant processing power and time, often requiring days or even weeks to complete a single run. This limitation severely restricts their utility in iterative design processes, where numerous simulations are needed to refine a system, and renders them impractical for real-time applications demanding immediate responses. Consequently, researchers frequently face a trade-off between the desire for detailed accuracy and the need for computational feasibility, prompting exploration into alternative modeling approaches that offer a more efficient balance.

The pursuit of understanding complex systems invariably presents a fundamental challenge: reconciling the desire for accurate representation with the constraints of computational resources. Detailed models, capable of capturing nuanced interactions, often demand prohibitive processing time and memory, effectively limiting the size and duration of simulations. Conversely, simplified models, while computationally efficient, may sacrifice critical details, leading to inaccurate predictions or a failure to capture emergent behaviors. This trade-off between fidelity and efficiency frequently restricts the scope of analysis, forcing researchers to focus on isolated aspects of a system rather than its holistic behavior, and ultimately hindering the ability to fully predict or control its dynamics. The core difficulty lies in the exponential growth of computational demands as system complexity increases, necessitating innovative approaches to model reduction and efficient simulation techniques.

The effective exploration of a complex system’s parameter space presents a significant hurdle to both optimization and accurate prediction. Traditional methods often rely on exhaustive searches or gradient-based techniques, which become computationally intractable as the number of parameters increases – a phenomenon known as the ‘curse of dimensionality’. Consequently, identifying optimal configurations or reliably forecasting system behavior requires navigating landscapes riddled with local optima, saddle points, and high-dimensional correlations. This difficulty stems from the fact that most complex systems exhibit non-linear responses, meaning small changes in input parameters can yield disproportionately large and unpredictable outcomes, thus demanding innovative approaches to efficiently sample and characterize the vastness of the parameter space.

A Conditional Dynamics Model for Surrogate Representation

Conditional Denoising Autoencoders (CDAEs) serve as the core component of the Conditional Dynamics Model (CDM) by establishing a learned mapping between noisy or incomplete system states and their corresponding clean or complete representations. This is achieved through an autoencoder architecture trained to reconstruct input data from a corrupted version, effectively learning the underlying data distribution. The ‘conditional’ aspect integrates input parameters, allowing the model to predict system dynamics specific to those conditions. This approach is particularly beneficial when dealing with limited data, as the CDAE learns to generalize from the available data by focusing on reconstructing essential features, thereby enabling the prediction of complex system behavior with fewer training examples than traditional methods.

CDM utilizes Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) to construct surrogate models characterized by high fidelity and robustness. DDPMs operate by progressively adding Gaussian noise to data until it becomes pure noise, then learning to reverse this process to generate new samples. This approach avoids mode collapse, a common issue in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), resulting in more diverse and realistic outputs. The resulting surrogate model accurately represents the underlying system dynamics and is capable of generating plausible system behaviors even with limited training data, effectively serving as a computationally efficient substitute for the original system.

Conditional Diffusion Modeling (CDM) facilitates efficient system exploration by integrating input parameters directly into the generative process. This conditioning allows the model to produce outputs – system responses – that are specifically tailored to given input conditions, without requiring separate training instances for each parameter combination. Instead of interpolating between known data points, CDM generalizes to unseen input values by leveraging the diffusion process, effectively creating a continuous mapping from input parameters to system behavior. This capability significantly reduces the computational cost associated with exploring a system’s response surface, particularly in high-dimensional parameter spaces, and enables rapid assessment of system performance under various operating conditions.

![An ablation study reveals that test accuracy is sensitive to the training noise scale [latex]\sigma_{max}[/latex], while adaptive step sizes accelerate convergence of time-independent CDM-0 models to around 50-80 iterations, and performance saturates with schedule resolution [latex]T \approx 30[/latex] and refinement steps [latex]K=1[/latex] as demonstrated with a sparse schedule [latex]T=3[/latex], all with standard deviations calculated across ten train-test-validation splits and logarithmic scaling on the y-axis.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21021v1/figures_V2/panel2V3.png)

Understanding System Manifolds and Validation

Conditional Diffusion Models (CDMs) operate on the principle that complex system states are not uniformly distributed across the entire possible state space, but instead cluster within a lower-dimensional subspace known as the Data Manifold. This manifold represents the set of physically plausible or valid system configurations. By implicitly learning this underlying manifold during training, the CDM can efficiently sample realistic states, avoiding the generation of improbable or invalid solutions. This approach enables robust prediction capabilities, as the model is constrained to operate within the bounds of physically meaningful states, reducing the risk of extrapolation errors and enhancing generalization performance.

Manifold learning techniques improve the generalization capability of the Conditional Data Manifold (CDM) by explicitly constraining the solution space to plausible system states. These techniques identify the underlying, lower-dimensional structure – the data manifold – within the high-dimensional data representing valid system behaviors. By learning this manifold, the CDM can extrapolate beyond the training dataset while avoiding physically implausible solutions that lie outside the learned subspace. This is achieved through algorithms that reduce dimensionality and preserve the essential relationships within the data, effectively regularizing the model and improving its robustness to unseen inputs and noisy data.

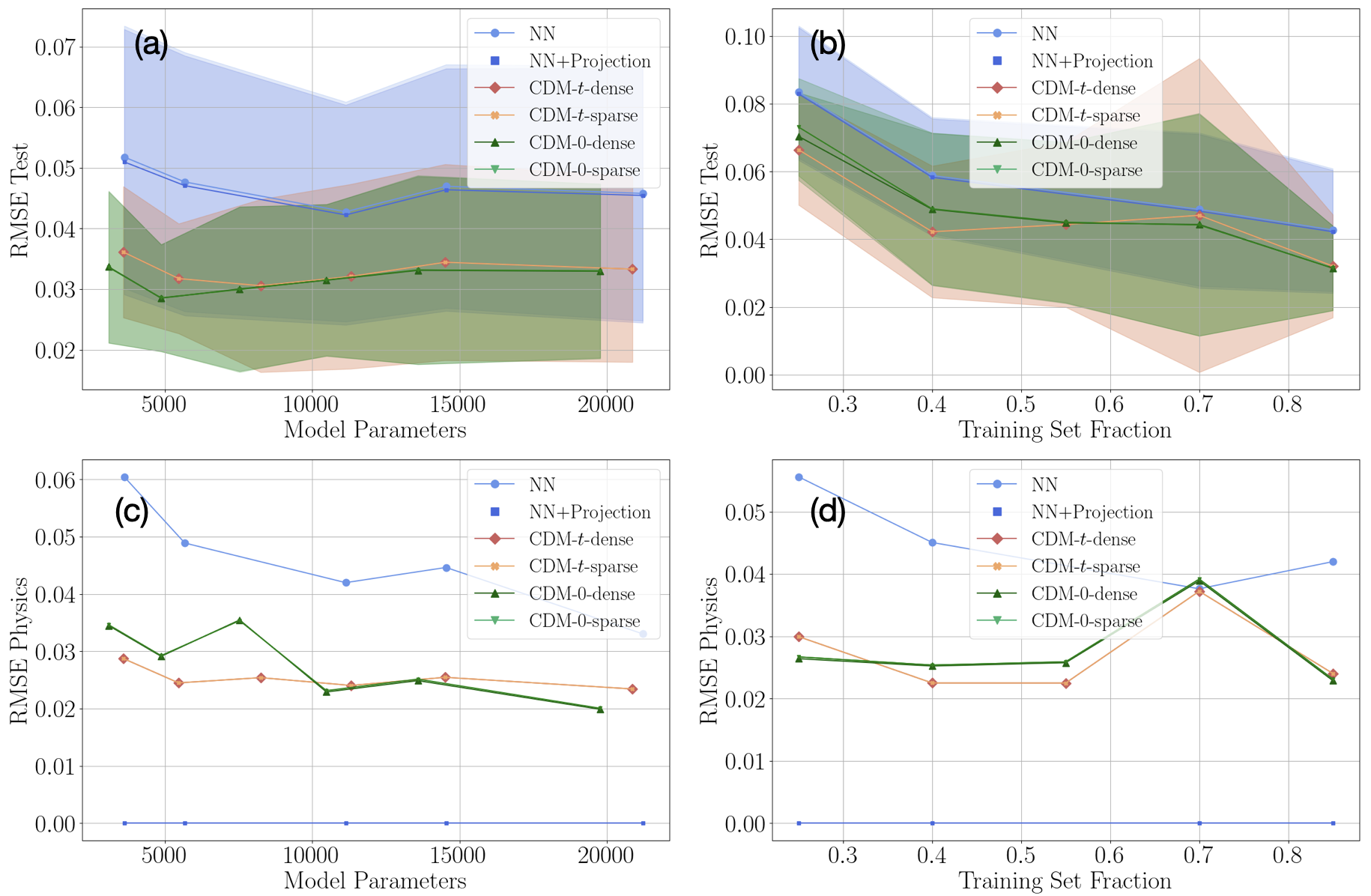

Model validation was performed by assessing the accuracy of predicted Steady-State Solution behaviors against results obtained from high-fidelity simulations. This comparison yielded a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of approximately 0.03, indicating a high degree of correlation between the model’s predictions and the established benchmark. The low RMSE value demonstrates the model’s capability to accurately represent system behavior and provides confidence in its predictive capabilities for scenarios beyond the training dataset.

Towards Enhanced Conditional Distributions and Future Impact

A robust evaluation of surrogate models hinges on accurately gauging their ability to replicate the conditional distributions of complex systems, and the Conditional DCD metric offers a rigorous solution. This approach moves beyond simple error calculations by explicitly comparing the model’s predicted probability distribution for a given input condition against the true data distribution. By quantifying the distance between these distributions, the metric reveals not only if the model predicts the correct mean value, but also how well it captures the inherent uncertainty and variability within the system – critical for reliable predictions, especially when extrapolating beyond observed data. Consequently, a lower Conditional DCD score indicates a closer alignment between the model’s predictions and the underlying physical reality, bolstering confidence in its performance across a range of conditions and ensuring accurate representation of the system’s behavior.

The model’s training leverages score matching, a technique that moves beyond traditional methods by directly optimizing the gradient of the data distribution. Instead of attempting to reconstruct data points, the model learns to accurately estimate the direction of steepest ascent – essentially, how the probability of observing data changes with slight variations. This approach proves particularly effective in complex, high-dimensional spaces where directly modeling the data distribution is challenging. By focusing on the gradient, the model efficiently captures the underlying structure of the data, leading to enhanced generative capabilities and improved performance in tasks requiring accurate probability estimation and sampling. The resultant model doesn’t simply mimic existing data; it learns the forces that shape the data, enabling it to generate novel and realistic samples.

Recent advancements in Conditional Distribution Distance (CDM) modeling have yielded time-independent variants that significantly streamline inference processes, paving the way for practical, real-time applications of this surrogate modeling technique. This simplification doesn’t come at the cost of accuracy; the refined model demonstrably reduces constraint violations, achieving a Physics Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of just 0.02-0.03. This represents approximately a 50% reduction in errors compared to traditional physics-informed models, indicating a substantial improvement in predictive capability and adherence to underlying physical principles. The increased efficiency and precision of these time-independent CDM variants expand the potential for deploying accurate and responsive surrogate models in a diverse range of time-critical applications, from rapid design optimization to real-time control systems.

The pursuit of accurate surrogate models, as detailed in this work, hinges on capturing the underlying structure of complex systems. This echoes John McCarthy’s sentiment: “It is better to solve a problem correctly than to solve it quickly.” The Conditional Denoising Model (CDM) prioritizes learning the solution manifold’s geometry-a nuanced approach that, while computationally involved, ultimately delivers enhanced data efficiency and predictive accuracy. The CDM doesn’t seek merely a fast approximation; it strives for a faithful representation of the physical system’s behavior, acknowledging that true elegance and robustness arise from understanding the whole, not just patching the parts. A fragile, quickly-built model, like a clever design, will inevitably falter; a structurally sound one endures.

The Road Ahead

The demonstrated efficacy of a Conditional Denoising Model as a surrogate rests, predictably, on the quality of the initial data and the implicit assumptions baked into the denoising process. The paper rightly highlights improved data efficiency, but efficiency is a local optimization. The true cost lies not in the quantity of data, but in the fidelity of the learned manifold. Current approaches treat manifold learning as a means to an end – prediction – rather than a fundamental characteristic of the physical system itself. Future work must address the question of which manifold is being learned, and whether that manifold is truly representative of the underlying physics, or merely a convenient interpolation surface.

The elegance of the CDM lies in its relative simplicity, but simplicity, as always, is a fragile victory. The architecture currently offers limited interpretability; a ‘black box’ surrogate, however accurate, offers little insight into the governing mechanisms. Expanding the model to incorporate explicit physical constraints – not as regularization, but as integral components of the denoising process – presents a significant, and likely thorny, challenge. Dependencies, in this context, are not merely lines of code, but the inherent limitations of any approximation.

Ultimately, the field will be defined not by increasingly complex models, but by a return to fundamental principles. The pursuit of accuracy should not eclipse the need for understanding. Good architecture, in any system, is invisible until it breaks – and in the case of scientific surrogates, ‘breaking’ means a failure to generalize beyond the training data, revealing the limitations of the learned representation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21021.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Heartopia Book Writing Guide: How to write and publish books

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) February 2026 Hilda’s “Guardian Battalion” Starlight Pass Details

- Genshin Impact Version 6.3 Stygian Onslaught Guide: Boss Mechanism, Best Teams, and Tips

- 10 Years Later, Taylor Sheridan’s Neo-Western ‘Hell or High Water’ Blasts Onto Netflix

- UFL – Football Game 2026 makes its debut on the small screen, soft launches on Android in select regions

- 10 One Piece Characters Who Could Help Imu Defeat Luffy

- 1st Poster Revealed Noah Centineo’s John Rambo Prequel Movie

- UFL soft launch first impression: The competition eFootball and FC Mobile needed

2026-02-02 06:34