Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores how readers perceive the quality and trustworthiness of research abstracts created with or by artificial intelligence.

A qualitative analysis reveals that disclosing AI assistance increases reader trust, but reliably identifying AI authorship remains a challenge.

Despite growing reliance on Large Language Models (LLMs) in academic writing, a critical gap remains in understanding how readers perceive and evaluate AI-generated scientific content. The study ‘LLM or Human? Perceptions of Trust and Information Quality in Research Summaries’ addresses this by investigating whether individuals can reliably distinguish between human- and LLM-authored abstracts, and how awareness of LLM involvement influences judgments of quality and trustworthiness. Findings reveal that participants struggle with accurate detection, yet perceptions of AI assistance significantly shape their evaluations, with LLM-edited abstracts receiving more favorable ratings. As LLMs become increasingly integrated into scientific communication, what implications do these findings hold for establishing norms around disclosure and responsible AI collaboration?

The Shifting Foundations of Scholarly Communication

The rapid advancement and increasing accessibility of Large Language Models (LLMs) are fundamentally reshaping the dissemination of scientific knowledge. These powerful tools, capable of generating human-quality text, are being employed across the research communication pipeline, from drafting manuscripts and summarizing findings to creating grant proposals and even peer review responses. This proliferation, however, introduces significant challenges to established norms of academic integrity and trust. As the line between human and machine authorship blurs, questions arise regarding the originality, accountability, and ultimately, the reliability of published research. The ease with which LLMs can produce convincing text necessitates a critical re-evaluation of how authenticity is verified and how readers assess the validity of scientific claims, potentially ushering in an era where discerning the source of information is paramount.

Historically, the evaluation of research quality has been deeply intertwined with the assumption of human authorship; peer review, grant applications, and academic promotion all implicitly prioritize work believed to originate from human intellect and effort. This foundational criterion is now fundamentally challenged by the increasing sophistication of artificial intelligence and its capacity to generate seemingly original content. The ability of Large Language Models to produce text that mimics human writing styles raises significant questions about how to accurately assess the validity, originality, and intellectual contribution of research when the perceived author may not be human. Consequently, existing metrics and processes for evaluating research are facing unprecedented scrutiny, demanding a re-evaluation of what constitutes trustworthy and impactful scholarship in an age of AI-generated content.

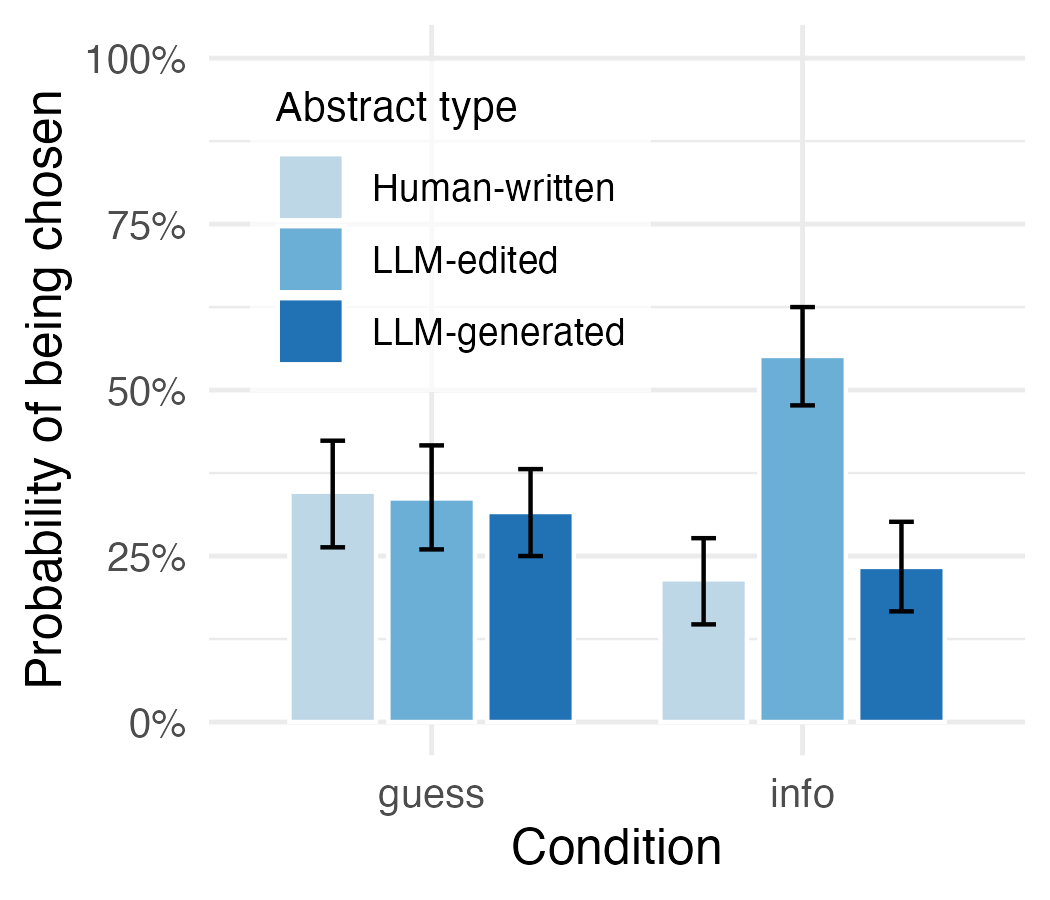

A recent investigation into the detection of AI-generated research content reveals a significant challenge for discerning authorship. Participants were presented with abstracts and tasked with identifying those written by Large Language Models versus human researchers; results indicated performance at chance levels, meaning readers were unable to reliably distinguish between the two. This finding underscores a critical vulnerability in current research communication, as the increasing sophistication of LLMs allows for the creation of convincingly human-written text. The inability to accurately identify AI authorship raises concerns about the potential for misinformation, compromised research integrity, and the erosion of trust in scientific findings, demanding a re-evaluation of how research quality and authenticity are assessed in the digital age.

The increasing prevalence of AI-generated content necessitates a focused examination of how individuals assess research communicated through abstracts. Determining whether a reader’s evaluation of a study is influenced by the perceived authorship – human or artificial intelligence – is paramount in an era where discerning content origin is becoming increasingly difficult. This evaluation isn’t simply about detecting AI; it concerns the fundamental processes of knowledge acceptance and trust in scientific findings. If readers are unable to reliably differentiate between human-written and AI-generated abstracts, the potential for biased interpretation or uncritical acceptance of research increases, demanding a deeper understanding of the cues and cognitive processes involved in evaluating scientific communication and potentially requiring new metrics for assessing research quality beyond traditional authorship.

Reader Orientations: A Spectrum of Presuppositions

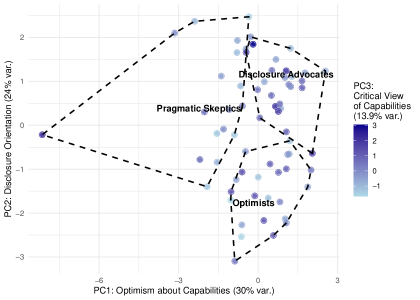

User reception of content generated by Large Language Models (LLMs) is not uniform; individuals exhibit a range of pre-existing beliefs regarding the technology’s capabilities and trustworthiness. Our research indicates that readers do not approach LLM-generated text neutrally, instead entering the evaluation process with varying degrees of optimism about the potential benefits, skepticism concerning its accuracy and reliability, or a focused advocacy for transparent disclosure of its generative source. These orientations, established prior to content exposure, act as filters through which subsequent assessments of quality and trustworthiness are made, suggesting a non-objective component in user evaluation.

Analysis of reader responses to LLM-generated content revealed three primary orientations impacting evaluation: ‘Optimists’, ‘Pragmatic Skeptics’, and ‘Disclosure Advocates’. Optimists generally express positive expectations and readily accept LLM outputs, while Pragmatic Skeptics demonstrate a cautious approach, actively questioning the reliability and potential biases of the generated text. These orientations are not merely surface-level preferences; statistical analysis indicates a strong correlation between a reader’s identified orientation and their subsequent assessment of content quality and trustworthiness, suggesting pre-existing beliefs fundamentally shape interpretation.

Our research indicates that 39.13% of participants prioritize transparency regarding the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in content generation. These individuals, identified as ‘Disclosure Advocates’, consistently expressed a belief that clear labeling of LLM involvement is crucial for establishing and maintaining reader trust. This orientation suggests a strong emphasis on informed consent and the ability to critically evaluate content knowing its origin, rather than assessing it solely on its presented merits. The substantial representation of this group within our participant base highlights the importance of addressing transparency concerns in the context of LLM-generated content.

Evaluations of Large Language Model (LLM)-generated content are not solely based on inherent qualities of the text itself, but are significantly modulated by the pre-existing beliefs of the reader. Analysis of participant data reveals that individuals identified as ‘Optimists’, ‘Pragmatic Skeptics’, or ‘Disclosure Advocates’ consistently applied different standards when assessing abstract attributes like quality and trustworthiness. Specifically, these orientations functioned as cognitive filters, influencing the interpretation of the same content; a passage deemed “high quality” by an Optimist may be viewed as “potentially misleading” by a Pragmatic Skeptic, even when controlling for objective textual features. This indicates that perceptions of LLM output are subjective and shaped by underlying attitudes toward the technology, rather than being purely objective assessments.

Methodological Rigor: Dissecting Reader Response

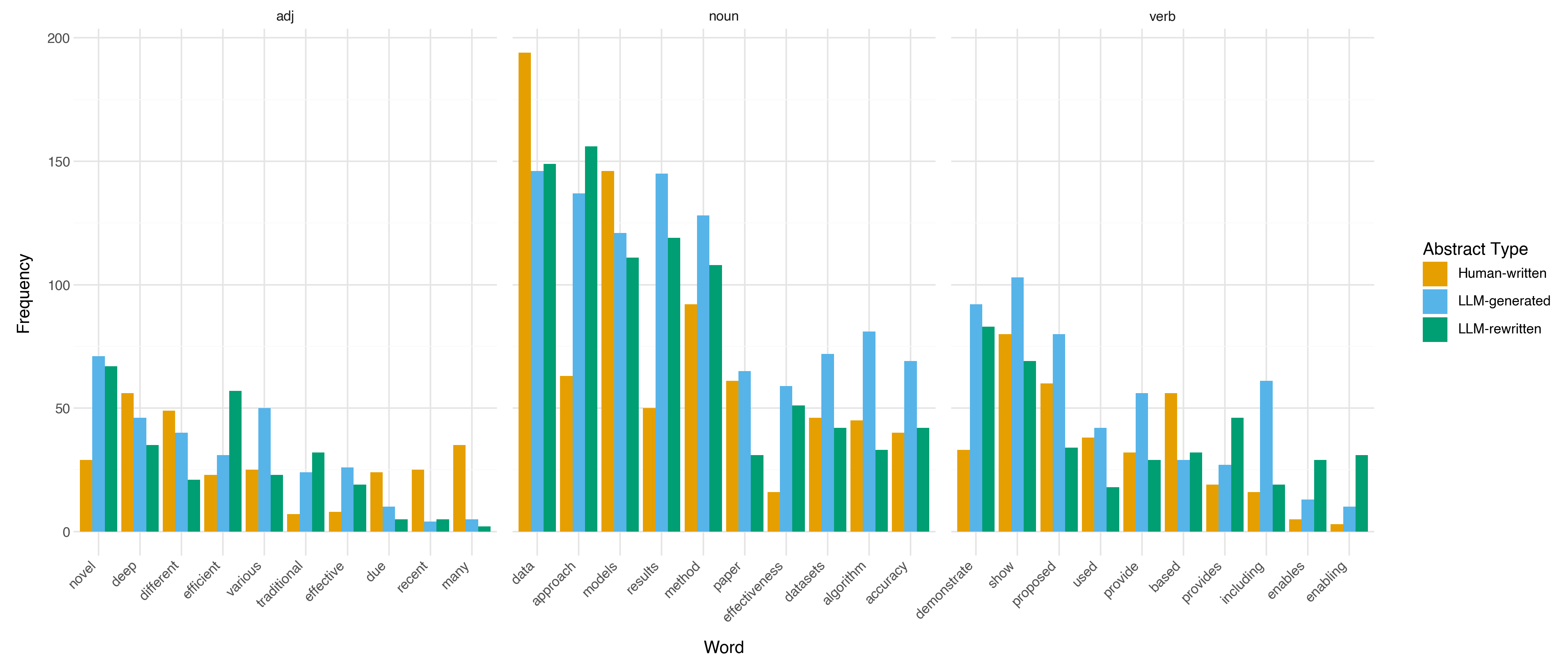

The study employed a comparative analysis of reader responses to three distinct abstract types: ‘HumanWrittenAbstract’s, crafted entirely by human researchers; ‘LLMGeneratedAbstract’s, produced solely by a large language model; and ‘LLMEditedAbstract’s, initially generated by an LLM and subsequently revised by human editors. This design allowed for a systematic evaluation of how abstract origin – human, machine, or hybrid – influences reader perception. Participants were presented with abstracts from a representative sample of academic papers, and their responses were collected via a standardized questionnaire and follow-up interviews. The abstracts were counterbalanced to minimize order effects and ensure equal representation of each type across the participant pool.

Thematic analysis, employed as the primary qualitative method, involved a systematic review of participant responses to identify recurring patterns of meaning related to the three abstract types. Inductive coding was utilized to develop these themes directly from the data, rather than imposing pre-defined categories; coders iteratively reviewed transcripts, identifying initial codes, grouping similar codes into broader themes, and refining these themes through ongoing analysis of the dataset. This iterative process ensured the identified themes accurately reflected participant interpretations and minimized researcher bias, allowing for a nuanced understanding of how readers engaged with and assessed the different abstract formats.

Analysis of participant responses focused on establishing correlations between reader characteristics – specifically, their pre-existing orientation towards AI-generated content – and their evaluations of the three abstract types: ‘HumanWrittenAbstract’s, ‘LLMGeneratedAbstract’s, and ‘LLMEditedAbstract’s. The investigation examined whether reader orientation influenced perceptions of abstract quality – encompassing clarity, conciseness, and overall effectiveness – and trustworthiness, defined as the perceived reliability and credibility of the information presented. Data was assessed to determine if statistically significant relationships existed between these variables, allowing for the identification of potential biases or preferences affecting reader judgment of each abstract type.

Implications for Scholarly Integrity: A Paradigm Shift

Research indicates that initial impressions significantly shape how readers perceive the quality of scientific abstracts, often overshadowing the actual writing itself. This phenomenon suggests that factors such as the perceived source or a pre-existing bias towards a particular research area can heavily influence evaluations, leading to discrepancies between objective quality and subjective assessment. The study revealed that participants frequently formed opinions based on superficial cues, demonstrating a tendency to prioritize readily available information over a thorough analysis of the content’s merits; this highlights a critical challenge for evaluating research in an era where information overload is commonplace and quick judgments are often favored over careful consideration.

Recent investigations reveal a surprising trend regarding the perception of AI-generated content: disclosing the use of large language models (LLMs) in the creation of abstracts actually enhances perceptions of both trustworthiness and quality. This finding directly contradicts earlier research documenting a “disclosure penalty,” where transparency about AI involvement typically led to diminished credibility. The current study suggests that acknowledging LLM assistance may be interpreted as a commitment to methodological rigor and honesty, potentially signaling that the work has undergone careful consideration and isn’t presented as solely human-authored. This shift in perception could be crucial, indicating that open acknowledgement of AI tools is not necessarily detrimental, and may, in fact, foster greater confidence in research outputs as AI integration becomes increasingly prevalent.

Recent studies reveal a surprising inability among participants to accurately identify whether an abstract was authored by a human or generated by a large language model. This finding underscores significant limitations in current authorship detection technologies, which often rely on stylistic or linguistic markers easily replicated by advanced AI. The consistent failure to differentiate between human and machine-written summaries suggests that existing methods are insufficient for reliably attributing authorship, raising concerns about potential misuse and the erosion of trust in scholarly communication. Consequently, the field requires innovative approaches to authorship verification that move beyond surface-level analysis and incorporate more robust indicators of genuine human contribution.

The proliferation of AI-generated content presents a fundamental challenge to maintaining research integrity and public trust in science. Findings suggest that, as AI tools become increasingly sophisticated, discerning between human and machine authorship is becoming demonstrably difficult, potentially eroding confidence in published research. This isn’t merely a question of detecting AI use, but of ensuring that the core principles of accountability and transparency remain central to the scientific process. Without robust mechanisms for verifying sources and evaluating content critically, the potential for misinformation and the unintentional spread of flawed research increases significantly, demanding a proactive shift towards emphasizing source transparency and rigorous content verification across all stages of scholarly communication.

The proliferation of AI-generated content necessitates a fundamental recalibration of how information is assessed. Rather than relying on assumptions about authorship, a heightened emphasis on critical evaluation is paramount. This involves actively scrutinizing content for internal consistency, logical reasoning, and factual accuracy, irrespective of its perceived origin. Simultaneously, greater transparency regarding the tools and processes used in content creation – including clear disclosure of AI involvement – is crucial for fostering trust and enabling informed judgment. Ultimately, a move away from passively accepting information and toward proactively verifying its validity represents a vital safeguard against misinformation and a cornerstone of intellectual honesty in an increasingly automated world.

The study illuminates a critical point regarding information assessment; readers, despite increasing exposure to AI-generated content, consistently struggle to differentiate between human and machine authorship. This aligns with a core tenet of robust system design. As Linus Torvalds aptly stated, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” The research demonstrates that simply claiming human authorship isn’t sufficient; verifiable provenance – disclosure of LLM assistance – directly influences perceived trustworthiness. The focus isn’t merely on whether an abstract ‘works’ – conveys information – but on the demonstrable, provable origins of that information, mirroring the emphasis on correctness and algorithmic purity over superficial functionality.

What’s Next?

The demonstrated susceptibility of readers to accept machine-generated text, even when demonstrably flawed, highlights a fundamental issue: trust is not earned through statistical mimicry, but through verifiable correctness. This research, while illuminating perceptions, skirts the more pressing question of truth. Disclosure of LLM involvement may paradoxically increase trust, but it does not address the potential for propagating inaccuracies at scale. The field now faces a critical divergence: will it focus on refining the illusion of human authorship, or on building systems that provide provably accurate summaries?

Future work must move beyond qualitative assessments of ‘trust’ and embrace rigorous quantitative analyses of factual fidelity. Can LLMs be constrained to operate within defined knowledge boundaries, and can these boundaries be mathematically verified? The current emphasis on ‘human-AI collaboration’ feels less like synergy and more like a convenient delegation of responsibility. The human remains accountable for the information presented, yet increasingly relinquishes the means to independently verify it.

In the chaos of data, only mathematical discipline endures. The challenge is not to make machines seem intelligent, but to construct algorithms whose outputs are demonstrably, provably correct – a task far more demanding than generating plausible text. The pursuit of ‘trust’ is a distraction; the goal should be unassailable accuracy, regardless of authorship.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15556.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Genshin Impact Version 6.5 Leaks: List of Upcoming banners, Maps, Endgame updates and more

2026-01-24 07:19