Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have discovered that simple ‘stopping’ interactions between individuals can surprisingly give rise to robust, synchronized flocking behavior.

![The system’s transition from disorder to collective order hinges on the introduction of halting interactions; without them, a disordered state remains stable, but with interactions set to a value of seven, ordered dynamics emerge as evidenced by trajectories of order parameters [latex]m, v_m, v[/latex] and phase plane analysis of a mean-field model-simulations with [latex]N=500[/latex] particles and parameters [latex]s_S=s_M=s_C=c_S=c_C=0.2[/latex], [latex]h\in\{0,7\}[/latex], and [latex]c_M=2[/latex]-demonstrate this shift.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15362v1/x2.png)

This study introduces a mechanism where halting upon encountering oppositely moving neighbors creates stable, large-scale collective movement, even with variable individual speeds and stochastic dynamics.

While prevailing models of collective animal behavior rely on alignment or noise-induced ordering, a comprehensive understanding of emergent flocking mechanisms remains elusive. This paper, ‘Flocking by stopping: a novel mechanism of emergent order in collective movement’, introduces a fundamentally different approach, demonstrating that stable, large-scale coordinated motion can arise not from individuals seeking consensus, but from a simple halting interaction-slowing or stopping upon encountering an oppositely moving neighbor. Through mean-field analysis and individual-based simulations, we reveal the conditions under which this ‘flocking by stopping’ behavior emerges, even with variable speed and limited interaction range. Could this previously unconsidered mechanism explain collective behaviors observed in diverse biological systems and inspire novel approaches to multi-agent control?

The Illusion of Order: Why Flocks Aren’t as Smart as They Seem

The spontaneous emergence of coordinated movement in groups – from flocks of birds and schools of fish to swarming insects and even human crowds – presents a longstanding puzzle across diverse scientific disciplines. This phenomenon, known as collective motion, isn’t simply a matter of individuals following a leader; rather, it arises from local interactions between individuals, each responding to the immediate environment and the actions of their neighbors. Understanding the principles governing this synchronization is crucial, as it touches upon fundamental questions in physics regarding self-organization and emergent behavior, and in biology, concerning the efficiency of foraging, predator avoidance, and social communication. Researchers posit that deciphering the mechanisms behind collective motion could unlock insights into complex systems far beyond the biological realm, potentially informing areas like robotics, traffic flow optimization, and even distributed computing.

Conventional approaches to understanding collective behavior frequently falter when attempting to replicate the spontaneous order observed in nature without invoking a central authority or intricate communication networks. These models often necessitate a leader or a complex signaling system to coordinate movement, a requirement rarely met in self-organizing systems like flocks of birds or schools of fish. The difficulty arises from the assumption that order requires direction; traditional physics often prioritizes externally imposed rules over the potential for patterns to emerge solely from local interactions. Consequently, these models struggle to accurately represent the robustness and adaptability of natural swarms, which maintain cohesion and navigate complex environments despite the absence of a designated leader or global plan. This limitation highlights the need for new theoretical frameworks that prioritize decentralized mechanisms and the power of simple rules to generate complex, emergent behaviors.

The limitations of existing explanations for collective motion have spurred the development of novel modeling approaches focused on the intricate relationship between individual actions and the resulting group dynamics. These models move beyond the assumption of centralized control, instead emphasizing that coherent patterns can emerge from local interactions – where each entity responds to its immediate neighbors without global coordination. Researchers are increasingly investigating how subtle variations in individual behavior, such as response time or preferred heading, can propagate through a group and ultimately shape the collective’s trajectory. This shift in focus allows for a more nuanced understanding of how complex, coordinated movements – from bird flocks and fish schools to human crowds – can arise spontaneously, driven by the interplay of simple rules and local sensing, rather than requiring a designated leader or pre-programmed plan.

The emergence of coordinated movement from simple interactions remains a central question in understanding collective behavior. Investigations reveal that order doesn’t necessarily require a leader or complex signaling; instead, it can spontaneously arise from local rules governing how individuals respond to their immediate neighbors. These rules, often based on alignment, attraction, and repulsion, allow self-propelled entities – be they birds flocking, fish schooling, or cells migrating – to maintain cohesion and navigate complex environments. The surprising robustness of these systems suggests that collective order is not a fragile state, but an inherent property of interacting agents, demonstrating that sophisticated global patterns can stem from remarkably simple local interactions-a principle with implications ranging from robotics to understanding biological swarms.

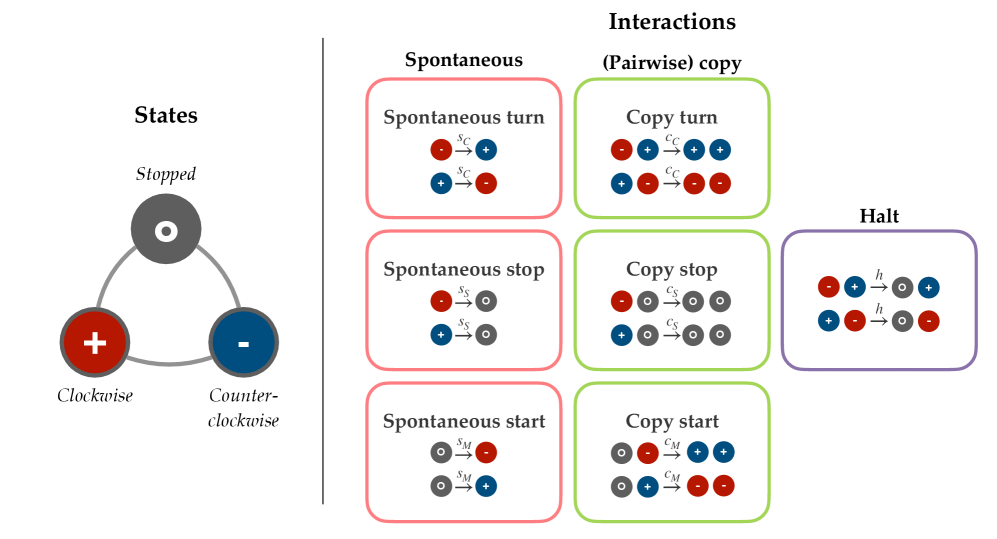

The Simple Rules That Govern the Swarm

The Vicsek model, a foundational element in the study of collective animal behavior, simulates the dynamics of self-propelled particles that update their heading based on the average direction of their neighbors within a defined radius. Specifically, each particle adjusts its direction by a small, randomly distributed angle towards the mean heading of nearby particles. This iterative process, applied to a population of agents, demonstrates that simple, local interaction rules – lacking any global control or centralized coordination – are sufficient to generate emergent, coordinated group motion. The model’s simplicity allows for detailed analysis of the relationship between individual behavior and collective patterns, providing a basis for investigating more complex systems and the influence of various parameters like particle density and the radius of interaction.

The Vicsek model demonstrates that collective motion isn’t solely dependent on precise, coordinated movements; rather, a degree of stochasticity is essential for group coherence. Initial simulations revealed that completely noise-free systems quickly converge to a single direction, losing the dynamic flocking behavior observed in natural systems. Conversely, excessive noise prevents any alignment. The model highlights a critical balance: fluctuations in individual movement directions, acting as a form of exploration, enable the group to avoid becoming rigidly fixed while simultaneously facilitating the discovery and maintenance of a shared, emergent direction. This suggests that noise isn’t simply a disruptive force, but an integral component in the self-organization process, allowing for adaptation and preventing stagnation in collective behaviors.

The order parameter, denoted as [latex]m[/latex], is a quantitative metric used to assess the degree of collective alignment within a system of agents. Calculated as the magnitude of the average normalized velocity vector across all agents, [latex]m[/latex] ranges from 0 to 1. A value of [latex]m = 0[/latex] indicates complete disorder, where individual agent velocities are randomly distributed. Conversely, [latex]m = 1[/latex] signifies perfect alignment, with all agents moving in the same direction. Intermediate values represent partial coherence, providing a precise measure of the system’s tendency towards collective motion; this parameter is crucial for analyzing the transition from disordered to ordered behavior and for comparing alignment levels across different simulations or experimental conditions.

Effective collective behavior necessitates a dynamic interplay between individual agency and group cohesion. Systems exhibiting synchronization, such as flocking birds or swarming robots, do not achieve order through strict uniformity; rather, a degree of individual variation and responsiveness to local interactions is critical. Complete suppression of individual freedom would lead to a rigid, brittle system susceptible to disruption, while a complete lack of coordination would result in dispersal. Optimal collective performance, therefore, relies on a balance where individuals maintain sufficient autonomy to react to changing conditions, but also adhere to rules promoting local alignment and, consequently, global order. This balance is not static; the relative weighting of individual freedom versus collective synchronization can vary depending on the specific task or environmental demands.

![Simulations of a stochastic flocking model reveal that noise can induce or facilitate order in small flocks ([latex]N=10[/latex]), creating states not predicted by mean-field theory, while larger flocks ([latex]N=100[/latex]) conform to theoretical expectations.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15362v1/x4.png)

Simplifying the System: Speed, Dimension, and the Illusion of Control

Current models of collective movement often utilize a constant-speed assumption for simplicity, which limits their ability to accurately represent biological systems. To overcome this, we implemented a one-dimensional framework allowing for variable-speed motion of individual agents. This simplification-reducing movement to a single spatial dimension-enables focused analysis of velocity changes and interactions while still capturing essential dynamics. By allowing each agent to independently adjust its speed, the model more realistically reflects the nuanced behavior observed in flocks, swarms, and other collective systems, and facilitates investigation of how variable speed contributes to emergent order.

The implementation of a one-dimensional model facilitates focused analysis of specific behavioral rules governing collective movement. A primary interaction within this framework is the “halting” interaction, defined as the cessation of movement by an individual upon encountering a neighbor traveling in the opposite direction. This rule is applied strictly to pairwise interactions; when two individuals approach each other, both immediately reduce their velocity to zero. The resultant effect of repeated halting interactions is a reduction in overall system velocity and the potential for the emergence of stable, ordered states despite the absence of any explicit coordination beyond this simple, local rule.

The implementation of a variable-speed, one-dimensional model, coupled with halting interactions, generates stable, ordered states within the simulated collective. This system demonstrates that complex, coordinated movement isn’t necessarily dependent on intricate, long-range interactions or centralized control. Specifically, stability arises from localized, pairwise interactions-where individuals adjust speed and halt upon encountering opposing movement-allowing for self-organization without the need for global information exchange. The resulting ordered states are characterized by consistent flow and minimal disruption, mirroring observed patterns in biological swarms and pedestrian dynamics, despite being governed by relatively simple interaction rules.

Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) approximation techniques, when applied to the one-dimensional model of collective motion, facilitate the derivation of equations predicting system-level behavior. This involves representing the discrete interactions of individuals as continuous stochastic processes, allowing for the application of tools from stochastic calculus. Specifically, the SDE approach transforms the problem into one where the evolution of the collective density function can be described by a Fokker-Planck equation. Analyzing this equation yields insights into the system’s steady-state distributions and collective velocity, providing a means to predict macroscopic properties like flow rate and density profiles as a function of parameters such as interaction range and halting thresholds. The resulting equations offer analytical predictions that can be validated against agent-based simulations, providing a rigorous framework for understanding collective dynamics.

A Mathematical Lens: Quantifying the Dance of the Swarm

A mean-field description simplifies the analysis of interacting agents by replacing individual interactions with an average effect. This approach utilizes [latex] ODEs [/latex] to model the deterministic, large-scale behavior of the system, focusing on average quantities. However, to account for inherent noise and fluctuations present in biological systems, [latex] SDEs [/latex] are also employed. These equations incorporate stochastic terms, representing random variations, and allow for a more realistic representation of the system’s dynamics. The combination of both [latex] ODE [/latex] and [latex] SDE [/latex] frameworks provides a robust and versatile tool for characterizing the collective behavior of the system, capturing both the dominant trends and the stochastic deviations.

The Chemical Langevin Method facilitates the derivation of stochastic differential equations (SDEs) from a microscopic, deterministic model by introducing stochasticity into the rate functions governing the system’s transitions. This is achieved by replacing the deterministic rate constants with random variables, effectively adding noise terms to the underlying equations. Specifically, each rate constant, [latex]k_i[/latex], is represented as [latex]k_i = \bar{k}_i + \sqrt{2\bar{k}_i}\xi_i(t)[/latex], where [latex]\bar{k}_i[/latex] is the deterministic rate and [latex]\xi_i(t)[/latex] is a Gaussian white noise term with zero mean and unit variance. Applying this transformation to the master equation and taking the limit of infinite system size yields the Fokker-Planck equation, from which the SDE governing the system’s evolution can be obtained using the Ito or Stratonovich interpretation.

The order parameter, denoted as [latex]v[/latex], serves as a quantitative measure of collective motion within the system. Specifically, [latex]v[/latex] represents the average velocity or speed of the group, calculated as the mean of individual agent velocities. A higher value of [latex]v[/latex] indicates a stronger degree of collective motion and alignment, while a value approaching zero signifies a disordered or stationary state. The magnitude of [latex]v[/latex] directly correlates with the system’s ability to maintain coordinated movement and resist disruptive forces, providing a key indicator for characterizing transitions between collective and individual behaviors.

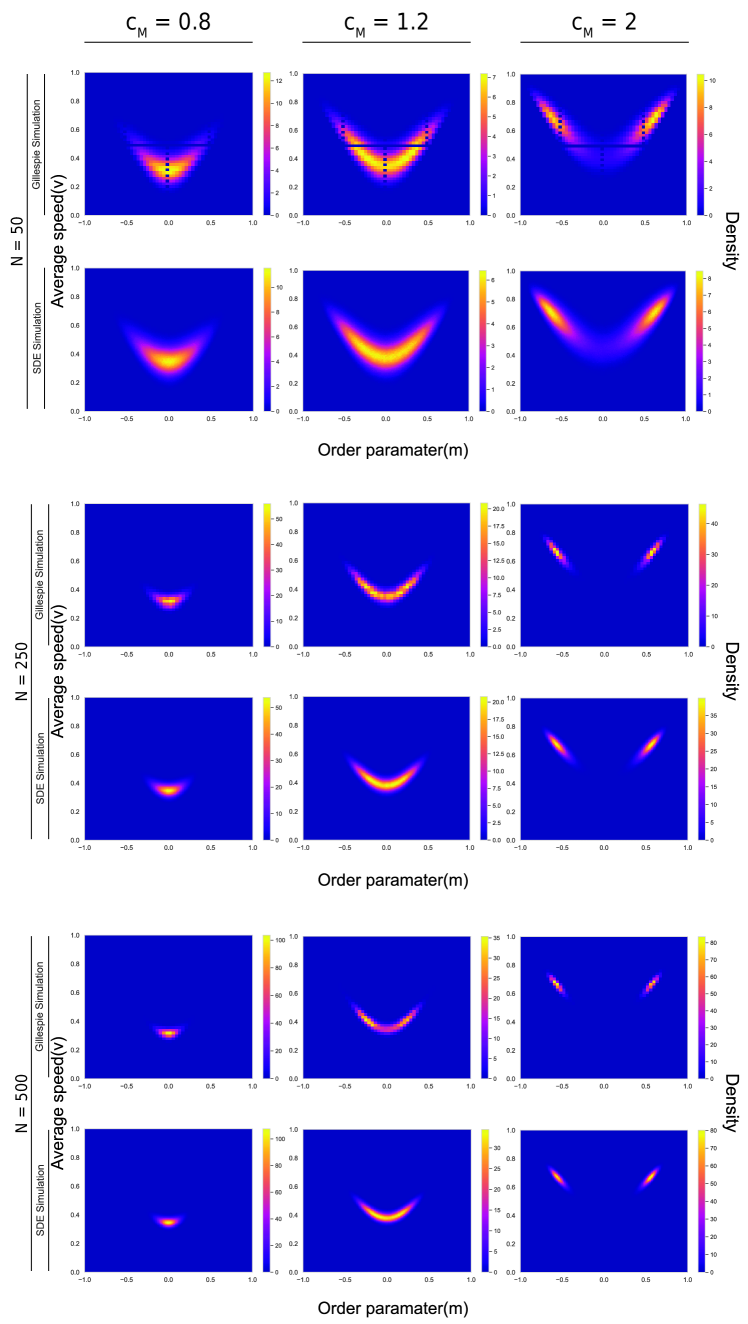

Validation of the Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) approximation was performed by comparing its predicted steady-state distributions to those obtained directly from the underlying microscopic model. Analysis of these distributions, as visualized in Figure 5, demonstrates a high degree of congruence between the SDE approximation and the full microscopic simulation. Specifically, the shapes of the distributions, including peak locations and overall spread, are consistent across both methods, indicating that the SDE accurately captures the essential statistical properties of the system’s long-term behavior. Quantitative metrics further confirm this alignment, establishing the reliability of the SDE as a computationally efficient alternative to simulating the complete microscopic dynamics.

A rigorous mathematical framework, utilizing both deterministic and stochastic modeling techniques – specifically Ordinary Differential Equations, Stochastic Differential Equations, and the Chemical Langevin Method – enables precise characterization of collective system dynamics. This approach moves beyond qualitative descriptions by providing quantifiable metrics, such as the order parameter [latex]v[/latex] representing average group speed, and allowing for the derivation of equations governing system evolution. Validation through comparison of predicted steady-state distributions with those obtained from the underlying microscopic model-as demonstrated in Figure 5-confirms the accuracy of the mathematical approximation and establishes a reliable basis for both understanding observed behaviors and making quantitative predictions about future system states.

![Collective order emerges deterministically only above a critical value of [latex]c_M[/latex], as evidenced by bifurcations in both order and speed when [latex]c_M[/latex] increases (with parameters [latex]s_S = s_M = s_C = c_S = c_C = 0.2, h = 7[/latex], and [latex]c_M \in [0, 5][/latex]).](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15362v1/x3.png)

The pursuit of elegant solutions in collective behavior invariably runs headfirst into the brick wall of reality. This research, detailing ‘flocking by stopping,’ feels less like a triumph of theory and more like a grudging acceptance of how things actually work. The researchers demonstrate order emerging from remarkably simple, almost clumsy, interactions – a halting response to opposing movement. It echoes a sentiment articulated by Mary Wollstonecraft: “The mind, when once accustomed to extensive views, is never satisfied with a narrow one.” The model doesn’t need complex calculations; it simply needs individuals reacting locally, a testament to the fact that global order often arises from local imperfections, a concept frequently lost in the quest for perfectly optimized systems. Tests, predictably, will reveal the limits of this halting mechanism, but it’s a start-a fragile, messy start.

What’s Next?

The elegance of ‘flocking by stopping’ lies in its parsimony – order emerging from what amounts to localized deceleration. Yet, the inevitable question arises: how robust is this mechanism when subjected to the indignity of real-world complexity? The current framework, while demonstrating stability in idealized conditions, largely sidesteps the issue of heterogeneous agent capabilities, dynamic environments, or even the simple addition of memory. Every abstraction dies in production, and this one will likely succumb to the peculiarities of non-uniform deceleration rates or the introduction of external forces.

Future work will undoubtedly explore the impact of these factors. A pressing concern is the scalability of the mean-field approximation. While computationally efficient, its validity degrades as system density increases or interactions become long-ranged. More granular, agent-based simulations, however, will merely trade computational cost for the eventual discovery of unforeseen edge cases. It’s a familiar trade-off.

Perhaps the most interesting avenue for exploration lies in extending this ‘halting interaction’ principle beyond simple alignment. Could similar deceleration-based mechanisms drive collective decision-making, foraging patterns, or even the formation of more complex social structures? The model suggests a pathway where constraint, rather than attraction, governs collective behavior. It’s a beautiful idea, and one that will almost certainly be broken. At least it dies beautifully.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15362.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Marshals Episode 1 Ending Explained: Why Kayce Kills [SPOILER]

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

2026-01-25 01:36