Author: Denis Avetisyan

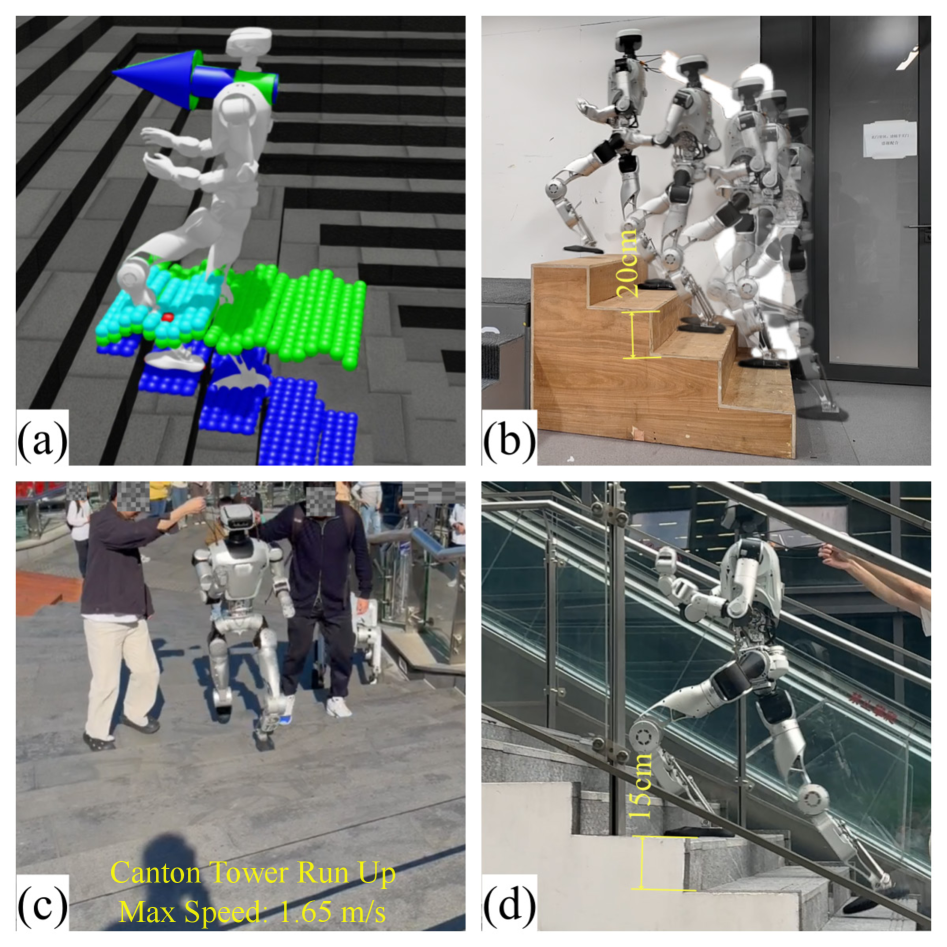

Researchers have developed a new framework that enables humanoid robots to ascend stairs at higher speeds while maintaining stability.

FastStair combines model-based planning and reinforcement learning with techniques like LoRA and parallel computing to address the agility-stability trade-off in stair climbing.

While humans effortlessly navigate stairs, replicating this agility and stability remains a significant challenge for humanoid robots. This work introduces FastStair: Learning to Run Up Stairs with Humanoid Robots, a novel framework that reconciles the strengths of model-based planning and reinforcement learning to achieve fast and stable stair ascent. By integrating a parallel foothold planner with a learned policy-fine-tuned via Low-Rank Adaptation-FastStair enables robust high-speed stair climbing, demonstrated on a physical robot achieving 1.65 m/s and completing a 33-step staircase in 12 seconds-performance that recently won the Canton Tower Robot Run Up Competition. Could this planner-guided learning approach unlock more dynamic and efficient locomotion for robots in complex, real-world environments?

The Dance of Instability: Replicating Locomotion

Humanoid robots promise a future of versatile assistance, yet replicating human locomotion, particularly in challenging spaces like staircases, presents a fundamental engineering hurdle. This difficulty stems from an inherent trade-off between stability and agility; robots designed for unwavering stability often lack the dynamic flexibility needed to negotiate uneven steps, while those prioritizing agility risk becoming unstable and falling. Unlike humans, who intuitively adjust gait and balance, robots require precise calculations and coordinated movements to maintain equilibrium during stair ascent and descent. This necessitates overcoming limitations in sensing, actuation, and control algorithms to enable robots to adapt to the unpredictable nature of real-world environments and consistently execute stable, efficient stair climbing.

Conventional control systems for bipedal robots frequently falter when confronted with the complexities of stair ascent, largely due to their reliance on meticulously detailed environmental models. These systems demand precise calculations of joint angles, velocities, and ground reaction forces to maintain stability, a computationally intensive task rendered impractical by real-world imperfections. Minute deviations – an uneven step, a slippery surface, or even slight inaccuracies in the robot’s self-localization – can cascade into significant errors, disrupting the delicate balance required for successful stair climbing. The inherent difficulty lies in creating a model robust enough to account for the unpredictable nature of dynamic environments, pushing researchers towards more adaptable and computationally efficient control strategies that prioritize real-time responsiveness over perfect predictive accuracy.

Achieving truly versatile locomotion demands more than simply executing pre-programmed movements; robots must dynamically adjust to unpredictable ground conditions and maintain equilibrium amidst disturbances. A robust control strategy isn’t merely about preventing falls, but about anticipating instability and proactively correcting it. This requires sophisticated sensing to perceive terrain variations – from subtle slopes to unexpected obstacles – coupled with algorithms capable of rapidly recalculating optimal foot placements and body postures. The challenge lies in creating a system that doesn’t rely on perfect environmental knowledge, but instead learns and adapts in real-time, much like biological systems do, enabling a fluid and resilient gait across diverse and uneven surfaces. This adaptability is paramount for deploying robots in real-world scenarios where pristine conditions are rarely guaranteed.

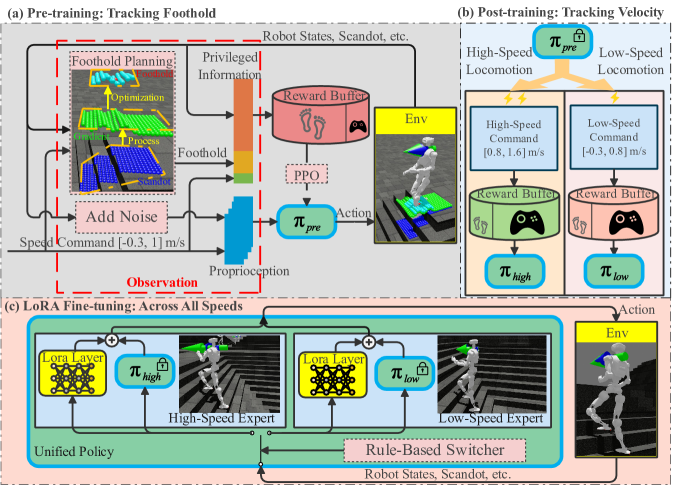

FastStair: A Hybrid Intelligence for Stair Negotiation

FastStair employs a hybrid architecture integrating model-based planning and reinforcement learning to address the challenges of rapid stair negotiation. The system initially utilizes a model-based planner to generate kinematically feasible and stable trajectories, providing a safe starting point for locomotion. Subsequently, reinforcement learning algorithms are applied to refine these trajectories, learning policies that optimize for speed and efficiency beyond the capabilities of the planner alone. This synergistic approach allows the robot to exploit the planner’s guarantees of stability while simultaneously benefiting from the learned agility and adaptability of reinforcement learning, resulting in enhanced stair climbing performance at higher velocities.

The FastStair system employs a Model-Based Planner to generate locomotion trajectories that prioritize stability and safety. This planning module utilizes a dynamic model of the robot and the stair environment to predict the outcome of potential movements. By simulating these movements, the planner identifies trajectories that avoid collisions and maintain balance throughout the stair climbing process. The generated trajectories are not simply kinematic paths, but consider the robot’s dynamics, including velocity, acceleration, and contact forces, to ensure feasibility and prevent falls. This proactive approach to motion planning forms the foundation for safe and reliable stair negotiation before any learned refinement is applied.

Following the generation of feasible trajectories by the Model-Based Planner, Reinforcement Learning (RL) is employed to optimize robot locomotion for speed and efficiency. The RL component learns a policy that refines these initial trajectories by iteratively adjusting control parameters based on reward signals. These rewards are structured to incentivize faster traversal of stairs while maintaining stability and avoiding falls. Through this learning process, the robot develops a nuanced understanding of how to modulate its movements – including step height, stride length, and body posture – to achieve optimal performance at varying stair configurations and speeds. The resulting learned policies enable more agile and natural stair climbing gaits compared to purely planned approaches.

The FastStair framework utilizes Velocity-Specialized Experts to improve stair-climbing performance across a range of speeds. These experts are individual control policies trained to optimize gait parameters – including step height, step length, and foot placement – for specific velocity bands. By employing a separate expert for each velocity range, the system avoids the need for a single, generalized policy that would necessarily compromise performance at either low or high speeds. This modular approach allows the robot to select and activate the most appropriate gait strategy based on the desired or current velocity, resulting in more efficient and agile stair negotiation. The experts are integrated into the overall control architecture, enabling seamless transitions between different gaits as the robot’s speed changes.

Efficient Computation: Accelerating the Dance

FastStair utilizes Parallel Discrete Search (PDS) as a core component to expedite the calculation of optimal footholds during locomotion planning. This approach significantly reduces computational demands by exploring a discrete set of potential foothold locations in parallel, rather than relying on continuous optimization methods. Benchmarking demonstrates that FastStair achieves a 25x speedup compared to state-of-the-art parallel Model Predictive Control (MPC) implementations when performing similar planning tasks. This performance gain enables real-time control capabilities, crucial for dynamic and reactive robot navigation, by allowing the system to rapidly adapt to changing environments and unexpected obstacles.

LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) facilitates the consolidation of multiple velocity-specialized expert policies into a unified model by applying low-rank matrices to the weights of a pre-trained model. This approach significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters compared to full fine-tuning, resulting in a decreased memory footprint and faster adaptation. Specifically, LoRA freezes the pre-trained model weights and injects trainable rank decomposition matrices into each layer of the Transformer architecture. During training, only these smaller LoRA matrices are updated, minimizing computational cost and memory requirements while maintaining performance comparable to full fine-tuning of all parameters.

Direct integration of footstep planning within the control framework enables precise specification and adjustment of robot foot placements during locomotion. This approach contrasts with systems that treat footstep planning as a separate, pre-processing step, allowing for dynamic adaptation to terrain variations and unexpected disturbances. By directly incorporating footstep planning into the control loop, the system can optimize foot placements for stability metrics, such as center of mass trajectory and ground contact forces, resulting in improved balance and robustness during walking and other complex maneuvers. This integration facilitates real-time adjustments to foot placements based on sensor feedback and predicted future states, contributing to more reliable and adaptable locomotion.

Training is conducted within the IsaacLab simulation environment, and employs Domain Randomization to improve performance in unseen conditions. This technique involves systematically varying simulation parameters – including textures, lighting, friction coefficients, and mass distributions – during training. By exposing the system to a wide range of randomized scenarios, the resulting policies become more robust to discrepancies between the simulated and real-world environments, thereby enhancing transferability to physical deployment without requiring extensive re-tuning.

Refining the System: Observation and Modeling

The robot’s learning process benefits significantly from a technique called Privileged Observation, wherein the training phase incorporates information beyond what the robot will have access to during actual operation. This supplementary data, available only during learning, acts as a guiding force, accelerating the acquisition of effective control policies. By providing the robot with insights into aspects of its state or environment that would be unobservable in the real world, the framework effectively ‘hints’ at optimal actions. This approach circumvents the challenges of learning directly from limited sensory input, enabling the robot to more rapidly and reliably develop the complex motor skills required for tasks like navigating challenging terrains. Consequently, the robot achieves improved performance and robustness, demonstrating an ability to adapt and execute maneuvers with greater precision and efficiency.

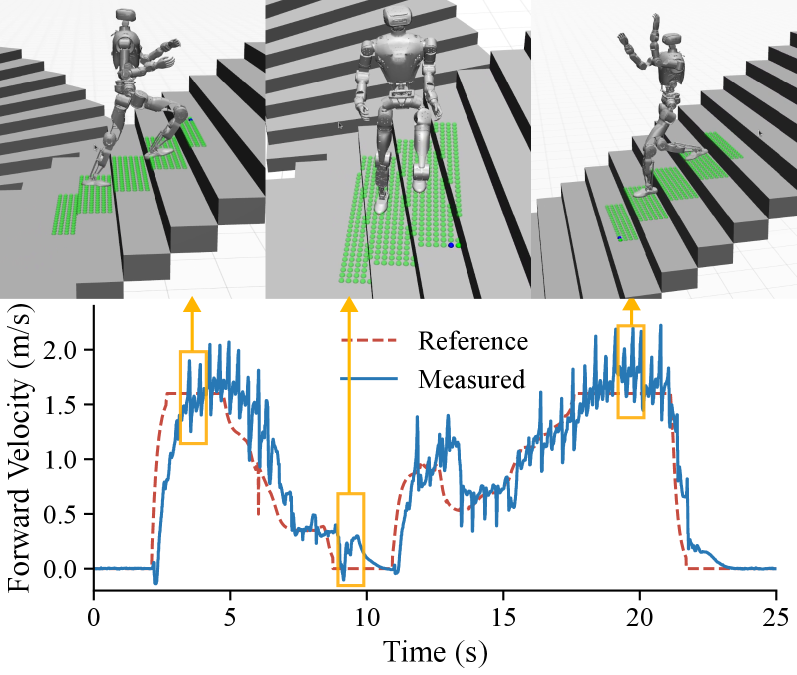

The robot’s ability to navigate dynamic environments hinges on its constant awareness of its own body state, achieved through proprioceptive observations. These internal measurements, gathered from sensors monitoring joint angles, velocities, and accelerations, provide a continuous feedback loop crucial for maintaining balance and adapting to unforeseen disturbances. By processing this data in real-time, the robot can proactively adjust its movements, compensating for uneven terrain or external forces without relying solely on external perception. This internal awareness enables the robot to maintain stability even when visual input is obscured or delayed, allowing for robust locomotion and successful navigation of complex environments like staircases – demonstrated by consistent performance at velocities up to 2.0 m/s with minimal velocity tracking error.

The robot’s ability to navigate complex terrains hinges on a streamlined understanding of its own movement, achieved through a dynamic model based on the Variable-Height Inverted Pendulum (VHIP) and implemented with the Divergent Component of Motion (DCM). This model intentionally simplifies the robot’s center of mass motion, representing it as an inverted pendulum whose effective height changes dynamically with its gait. By focusing on this core principle, the DCM allows for efficient computation of desired motions and stabilization, effectively decoupling the upper-body motion from the foot placement. This approach bypasses the need for computationally expensive full-body inverse kinematics, offering a balance between accuracy and real-time performance critical for agile locomotion and allowing the robot to rapidly adapt to unexpected disturbances or changes in terrain.

Accurate environmental perception proved vital to the robot’s successful navigation, achieved through integration of the RealSense D435i depth camera. This sensory input enabled the robot to reconstruct the surrounding terrain, facilitating robust path planning and dynamic adjustments during locomotion. The culmination of this work was a physical demonstration of the robot autonomously navigating a challenging 33-step spiral staircase in just 12 seconds, reaching a peak velocity of 1.65 m/s. Notably, the robot achieved a success rate exceeding 70% on staircases with a 25cm step height at 2.0 m/s, demonstrating a high degree of reliability, and maintained precise velocity control with a mean absolute error of only 0.5 m/s.

![The system perceives terrain features using scandots [blue], averaged gradients [green and light blue], and identifies optimal footholds [red] to facilitate stable locomotion.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.10365v1/pic/scandot1.png)

FastStair embodies a spirit of relentless testing, pushing the boundaries of what’s considered stable locomotion for humanoid robots. The framework doesn’t shy away from the inherent chaos of high-speed stair climbing, instead integrating model-based planning and reinforcement learning to navigate the trade-off between agility and stability. This iterative approach-learning through both prediction and real-world experience-aligns perfectly with Linus Torvalds’ assertion: “Most good programmers do programming as a hobby, and then they get paid to do it.” The pursuit of efficient, dynamic movement isn’t merely about achieving a functional outcome; it’s a fundamental exploration of robotic capability, driven by intrinsic curiosity and a willingness to dissect and rebuild systems until they perform as intended.

Where Do the Steps Lead?

The pursuit of rapid, stable locomotion for humanoid robots invariably exposes the brittle core of current control paradigms. FastStair rightly identifies the agility-stability paradox, offering a synthesis of model-based planning and reinforcement learning. Yet, the very success of this framework invites further deconstruction. The current reliance on pre-defined stair geometries, while pragmatic, begs the question: how readily can this system generalize to arbitrary, imperfect, or dynamically changing staircases? True intelligence doesn’t require a perfectly rendered simulation; it demands robustness against the unexpected.

Future work will likely necessitate a shift from meticulous planning to opportunistic adaptation. The integration of tactile sensing-allowing the robot to feel its way forward-could provide crucial feedback for correcting errors and anticipating disturbances. Moreover, the computational demands of parallel processing, while addressed, represent an ongoing challenge. Scaling these algorithms to operate in real-time on resource-constrained hardware remains a significant hurdle. The system isn’t simply about climbing faster; it’s about doing so with minimal prior knowledge and maximal resilience.

Ultimately, FastStair is not a destination, but a provocation. It compels a re-evaluation of what constitutes ‘understanding’ in robotics. Is it the creation of ever-more-complex models, or the development of algorithms that can learn and improvise in the face of inherent uncertainty? The answer, predictably, lies not in eliminating the chaos, but in mastering it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10365.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2026-01-17 20:17