Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a dual-encoding method to stabilize causal discovery when dealing with mixed data types, leading to more reliable and interpretable AI explanations.

This work introduces a novel causal discovery technique that addresses numerical instability in datasets with both categorical and continuous features using a dual-encoding constraint-based approach.

While understanding feature relationships is crucial for explaining machine learning decisions, traditional causal discovery methods struggle with datasets containing both categorical and continuous variables due to instability in conditional independence testing. This limitation is addressed in ‘Causal Discovery for Explainable AI: A Dual-Encoding Approach’, which introduces a novel technique employing complementary encoding strategies and majority voting to construct more robust causal graphs. The proposed dual-encoding approach successfully identifies interpretable causal structures, as demonstrated on the Titanic dataset, offering improved performance over existing methods. Could this technique unlock more transparent and reliable AI systems by providing a clearer understanding of underlying data dependencies?

The Erosion of Conventional Analysis: When Correlation Fails

Modern datasets frequently integrate diverse information – numerical measurements, categorical labels, textual descriptions, and even spatial data – creating what are known as mixed data types. This heterogeneity presents a significant hurdle for conventional statistical methods and machine learning algorithms, which are often designed to handle only a single data type or assume all variables are amenable to the same analytical approach. Techniques like linear regression or standard clustering algorithms struggle when applied directly to such datasets, potentially leading to biased results or a failure to identify meaningful patterns. The challenge lies in effectively representing and integrating these disparate data types, requiring specialized methods capable of accommodating both the nature and scale of each variable to unlock the full potential of the data.

Conventional correlation analyses, while useful for identifying simple relationships, frequently stumble when confronted with the intricacies of real-world datasets. These methods primarily detect linear associations, meaning they struggle to recognize dependencies that are non-linear, such as exponential or cyclical patterns. More critically, correlation does not imply causation; a statistical link between two variables doesn’t reveal whether one directly influences the other, or if both are affected by a hidden, confounding factor. Consequently, relying solely on correlation can lead to misinterpretations and flawed conclusions, especially when investigating systems with feedback loops, emergent behavior, or complex interactions between numerous variables – ultimately obscuring the true underlying mechanisms at play within the data.

Conventional statistical analyses frequently rely on assumptions of linearity and specific data distributions – such as the normal distribution – which can severely restrict the scope of discovered relationships. These methods often struggle when confronted with the inherent non-linearities and complex patterns present in real-world data, leading to an underestimation of true dependencies or, worse, the identification of spurious correlations. For instance, a simple linear regression might fail to detect a U-shaped relationship between variables, incorrectly suggesting no association exists. Furthermore, deviations from assumed distributions can invalidate the statistical significance of results, potentially masking genuine effects or inflating the importance of random noise. Consequently, researchers increasingly recognize the need for more flexible and robust analytical techniques capable of accommodating the complexities of diverse datasets, moving beyond the limitations of traditional methods to unlock a more complete understanding of underlying phenomena.

![A decision tree trained on the Titanic dataset, prioritizing splits on [latex]Sex[/latex], [latex]Pclass[/latex], and [latex]Age[/latex], reflects the causal relationships established by the Functional Causal Inference (FCI) method.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21221v1/titanic_graphs/titanic_tree.png)

Reconstructing the Causal Fabric: A New Analytical Approach

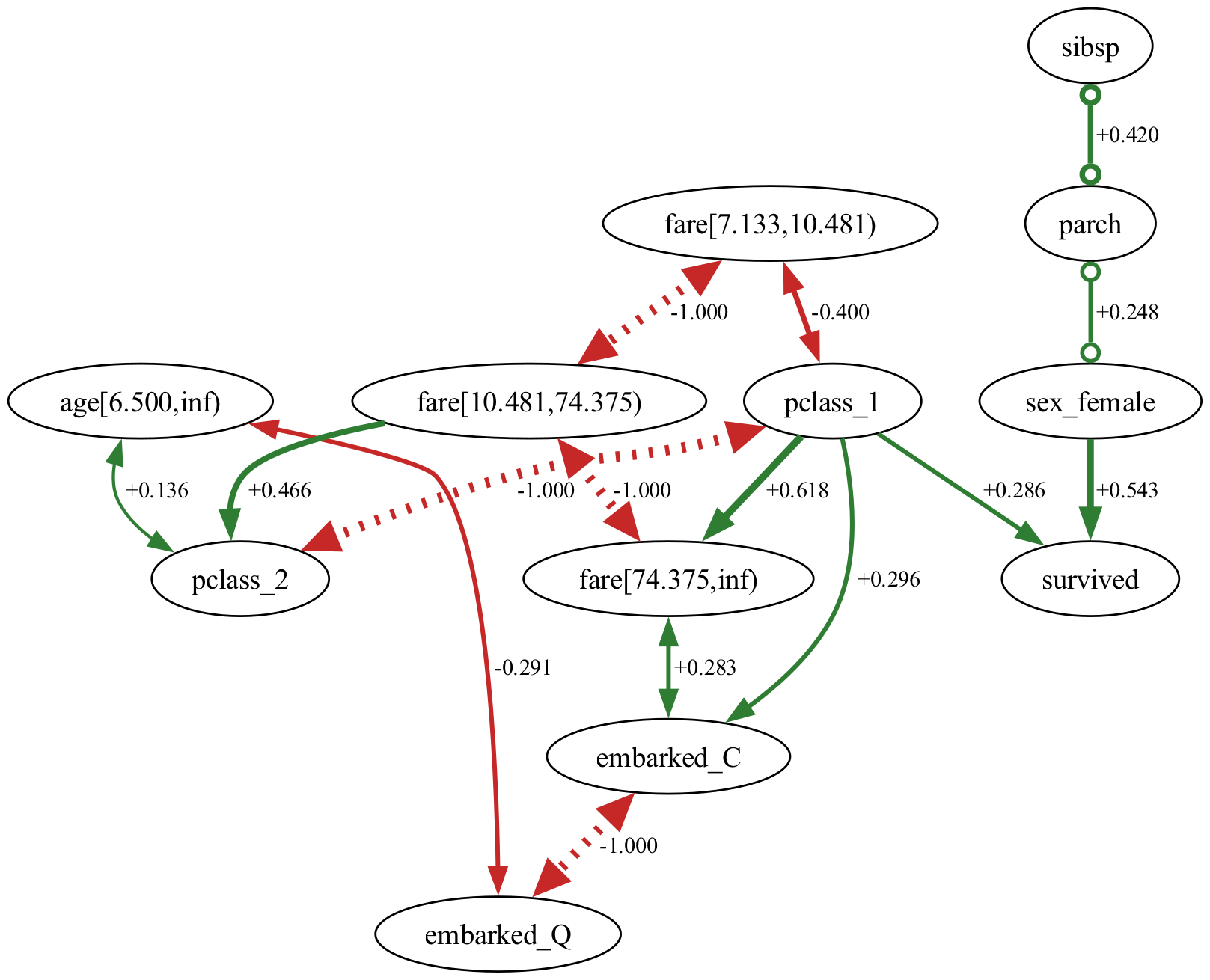

The Fast Causal Inference (FCI) algorithm, a constraint-based method for causal discovery, was utilized to infer causal relationships from a mixed dataset containing both continuous and categorical variables. Standard implementations of FCI are designed primarily for continuous data; therefore, adaptations were necessary to effectively process the categorical features. This involved modifying the conditional independence tests performed by FCI to accommodate the discrete nature of categorical variables, ensuring accurate assessment of potential causal links within the combined dataset. The algorithm identifies potential causal relationships by iteratively testing for conditional independence between variables and constructing a Partially Oriented Ancestral Graph (POAG) representing the inferred causal structure.

The inclusion of categorical variables in causal discovery presents challenges due to potential rank deficiencies in the data’s covariance matrices, hindering accurate estimation of partial correlations. To mitigate this, a Dual-Encoding Strategy was implemented, representing each categorical feature with two distinct numerical encodings: Drop-First and Drop-Last. Drop-First encoding omits the first category as a reference, while Drop-Last uses all categories except the final one. This dual representation effectively doubles the number of features considered during the causal inference process, providing two perspectives on the same categorical information and improving the robustness of the partial correlation estimation required by the Fast Causal Inference (FCI) algorithm.

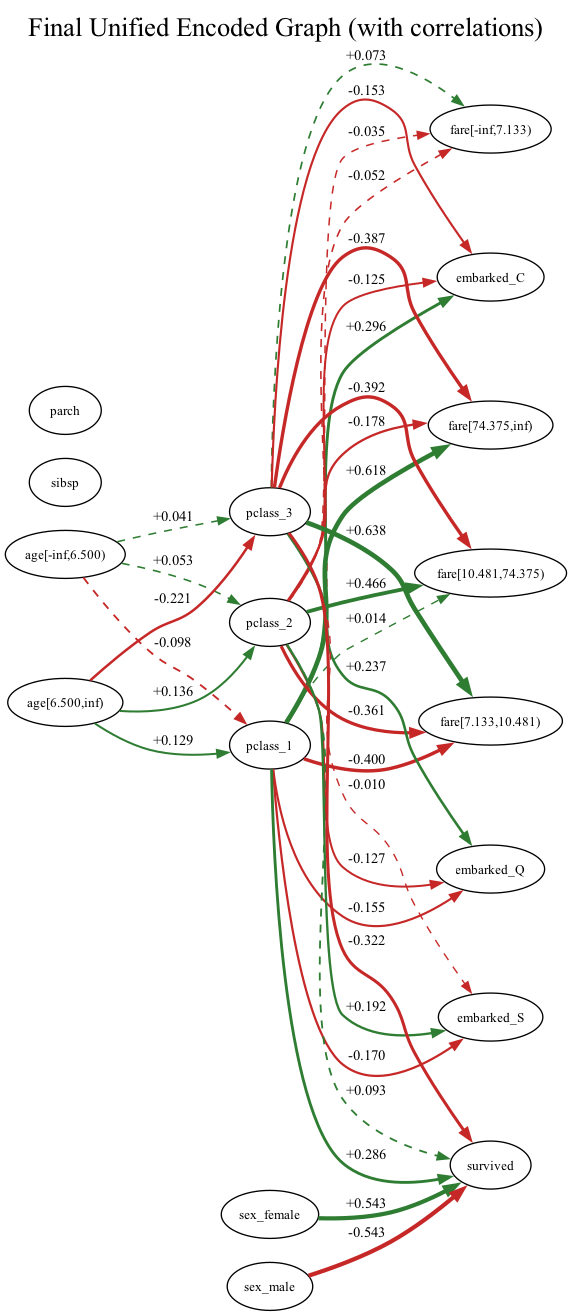

The causal graphs derived from both Drop-First and Drop-Last encoding strategies were combined using a majority voting approach to generate a unified causal graph. This process resulted in a graph comprising 17 feature nodes, representing the variables under investigation. The resulting graph structure is defined by 15 positively correlated edges, indicating a direct positive relationship between the connected nodes, and 17 negatively correlated edges, representing inverse relationships. The majority voting scheme prioritized edges present in both independently generated graphs, effectively consolidating the findings from each encoding method into a single, representative structure.

Implementation of the Fast Causal Inference (FCI) algorithm utilized a significance level (alpha) of 0.01 to establish statistical significance in determining potential causal relationships. This alpha value dictates the probability of falsely identifying an edge between two variables when no true relationship exists; a value of 0.01 indicates a 1% tolerance for Type I errors. All statistical tests conducted within the FCI algorithm, including conditional independence tests, were evaluated against this threshold. Edges were only included in the resulting causal graph if the corresponding p-value from the statistical test was less than 0.01, ensuring a stringent criterion for inferring causal connections.

Validating the Foundations: Assumptions and Algorithm Performance

The validity of causal inferences derived from our method is contingent upon two fundamental assumptions: Causal Sufficiency and Faithfulness. Causal Sufficiency stipulates that all common causes of any two variables in the dataset are observed and included in the analysis; the absence of unobserved confounders is critical for accurate causal identification. Faithfulness, conversely, assumes that all conditional independencies observed in the data are a direct result of the underlying causal structure, and that there are no accidental cancellations of effects that might mask true causal relationships. Violations of either assumption can lead to incorrect estimations of the causal graph and, consequently, flawed conclusions about feature importance and predictive modeling.

The Fast Causal Inference (FCI) algorithm is predicated on the Causal Markov Condition, which formally states that a variable is probabilistically independent of its non-descendants in the causal graph, conditional on its direct causes – its parents. This implies that all relevant information about a variable’s effect on any other variable is transmitted through its immediate successors, and any remaining dependence between a variable and its non-descendants can be explained by the conditioning on its parents. Mathematically, if [latex]X[/latex] is a variable and [latex]Y[/latex] is a non-descendant of [latex]X[/latex], then [latex]P(Y | X, Pa(X)) = P(Y | Pa(X))[/latex], where [latex]Pa(X)[/latex] represents the parents of [latex]X[/latex]. This condition is crucial for identifying potential causal relationships from observational data by establishing a framework for determining conditional independence and, subsequently, the structure of the underlying causal graph.

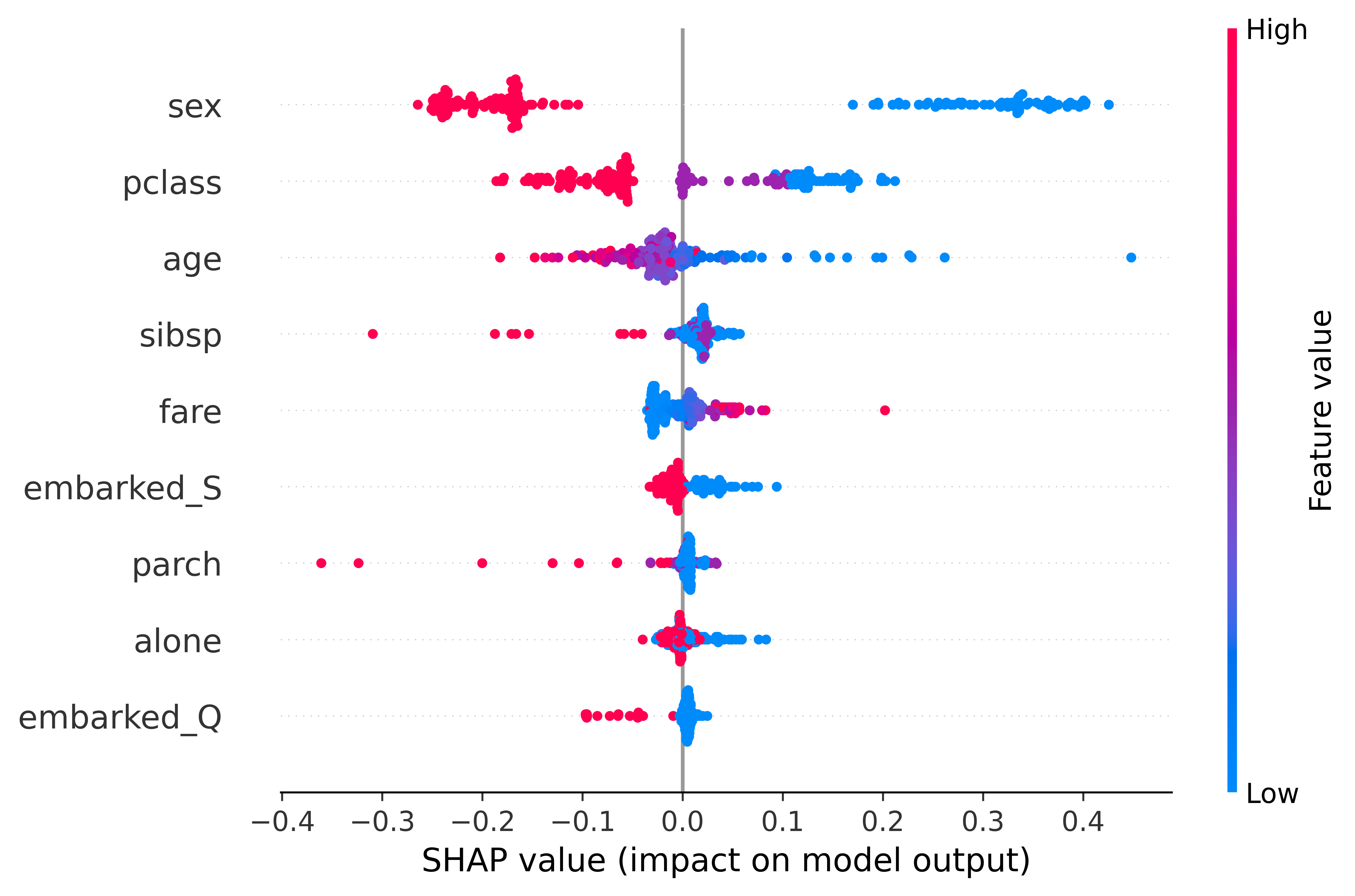

Evaluation of the causal discovery approach was conducted using the Titanic dataset to assess its performance in identifying relationships beyond predictive accuracy. Standard machine learning models, specifically a Decision Tree achieving 82% accuracy and a Random Forest with 84% accuracy, were implemented for comparison. The Random Forest model’s feature importances were then analyzed using SHAP values to validate the identified causal links, demonstrating the approach’s ability to uncover relationships that are not simply correlative but potentially indicative of underlying causal mechanisms, exceeding the capabilities of traditional predictive modeling.

Performance of the causal discovery approach was quantitatively assessed using the Titanic dataset, yielding an accuracy of 82% with a Decision Tree classifier and 84% with a Random Forest classifier. The Random Forest model was specifically selected for subsequent SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis. This analysis was conducted to validate the identified feature importances, providing a mechanism to assess the plausibility of the discovered causal relationships by examining the contribution of each feature to the model’s predictions.

Beyond Prediction: Towards Causal Transparency and Instance-Level Explanations

A central benefit of uncovering a causal graph lies in its ability to move beyond simply knowing what a model predicts to understanding why a specific prediction was made for a given instance. This graph doesn’t merely highlight correlations; it maps out the underlying mechanisms driving the model’s decisions, offering a structural framework for dissecting each prediction. By tracing the path of causal influence from input variables, through intermediate factors, to the final output, researchers can pinpoint the precise features and relationships that were most influential in that particular case. This approach provides a granular level of explanation, revealing how the model responds to unique combinations of circumstances and ultimately fostering greater insight into its internal reasoning process.

The true power of a discovered causal graph lies in its ability to dissect individual predictions, revealing the specific factors that drove a model’s output for a given instance. Rather than relying on aggregate feature importance, this approach merges the structural insights of the causal graph with the unique data characterizing each prediction. By tracing the activation of causal pathways for a particular instance, researchers can pinpoint the precise variables and relationships responsible for the outcome. This allows for a granular understanding of model behavior, moving beyond simply knowing which features are generally important to understanding why a model made a specific decision in a specific case, ultimately fostering greater trust and enabling more targeted interventions.

Traditional machine learning interpretability often relies on global feature importance – identifying which features generally influence a model’s predictions across the entire dataset. However, this provides a limited view, obscuring how features interact for specific instances and potentially misrepresenting the true drivers of individual outcomes. This new approach transcends this limitation by dissecting the causal mechanisms at play for each prediction, offering a more granular and actionable understanding. Instead of simply knowing a feature is important overall, one can pinpoint precisely how it influenced a particular result, revealing complex relationships and nuanced behaviors previously hidden within the model. This moves beyond broad generalizations to deliver insights tailored to individual cases, fostering greater trust and enabling more informed decision-making based on the model’s outputs.

Investigations are now directed towards integrating discovered causal structures within Argumentation Frameworks, a move poised to revolutionize how machine learning models justify their individual predictions. This approach doesn’t simply identify that a decision was made, but constructs a reasoned argument for it, detailing the specific evidence and causal pathways that led to that outcome for a particular instance. By framing predictions as logically supported claims, researchers aim to move beyond mere transparency – revealing how a model functions – to genuine explainability, fostering increased trust and enabling users to confidently understand, and even challenge, the rationale behind each decision. This nuanced level of justification is anticipated to be crucial for deploying machine learning in sensitive domains where accountability and user acceptance are paramount.

The pursuit of explainable AI, as detailed in this work concerning dual-encoding causal discovery, inherently acknowledges the temporal nature of systems. The instability addressed by this approach – arising from mixed data types – isn’t merely a technical hurdle, but a symptom of systems evolving beyond their initial design assumptions. As Brian Kernighan aptly stated, “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code first, debug it twice.” This resonates deeply; the need for robust causal inference, capable of handling real-world data complexities, represents a debugging process for the very models attempting to understand those systems. The dual-encoding method, in essence, seeks to ‘debug’ the causal discovery process, allowing for a more graceful aging of the AI itself.

What’s Next?

This work addresses a predictable fragility: the numerical instabilities inherent in applying formal methods to the messy realities of mixed data. The dual-encoding approach is, in essence, a stabilization technique-a bracing against the inevitable entropy of computation. Logging this process is the system’s chronicle, revealing where the constraints hold and where they fray. Deployment is merely a moment on the timeline, a snapshot of robustness before the data shifts again.

The true challenge isn’t merely constructing a causal graph, but maintaining its fidelity over time. Current constraint-based algorithms, even with this improvement, remain brittle. Future work must grapple with dynamic systems – those where conditional independence relationships aren’t fixed, but evolve. A graph is a static representation of a flowing process, and the gap between the map and the territory will only widen with complexity.

Ultimately, the field needs to consider not just finding causality, but measuring the confidence in that discovery. A graph without error bars is a fiction. The next iteration must move beyond structural identification and towards quantifying the uncertainty inherent in any inference-acknowledging that all models are, fundamentally, temporary approximations of an ever-changing reality.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21221.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Alan Ritchson’s ‘War Machine’ Netflix Thriller Breaks Military Action Norms

- Robots Learn by Example: Building Skills from Human Feedback

- ‘The Bride!’ Ending, Explained

- Is XRP Headed to the Abyss? Price Dips as Bears Tighten Their Grip

2026-01-30 09:40