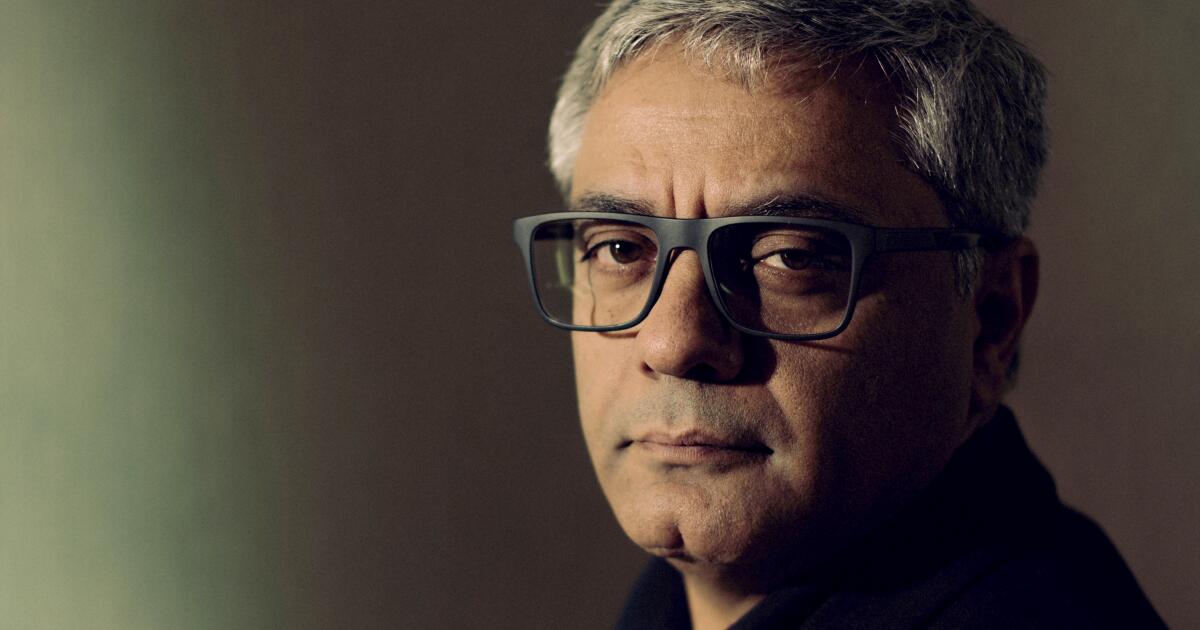

As I delve into the compelling story of Mohammad Rasoulof, a filmmaker who has bravely navigated the treacherous waters of censorship and persecution in his native Iran, I find myself deeply moved by his resilience and indomitable spirit. His journey is a testament to the power of art as a means of expression, resistance, and hope amidst adversity.

Approximately thirty minutes prior to our chat, Mohammad Rasoulof, an exiled Iranian filmmaker, received sad news from his homeland.

Kianush Sanjari, a journalist and activist with whom he’d shared time in prison, has tragically taken his own life by leaping from a building. This is what a deeply affected director shares with me through an interpreter, while we sit in the deserted restaurant of a West Hollywood hotel. He describes Kianush as someone who saw his body as a powerful tool for protest.

After a brief pause, I inquire if it’s alright to postpone, but he chooses to carry on with the conversation. Overcoming the seemingly impossible is now essential for him.

For decades, Rasoulof, aged 52, has faced regular scrutiny by Iranian officials due to the themes in his films criticizing the Islamic government’s use of violence against its people. Since 2010, he has been convicted on numerous occasions, prohibited from filmmaking, and served several prison sentences.

To dodge an eight-year prison term that also included a lashing, Rasoulof left Iran in May following the government’s request for him to withdraw his most recent, impactful film, “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” from the Cannes Film Festival where it was selected to compete. He chose not to oblige and instead decided to depart.

Following a challenging hike across unspecified mountain ranges on foot, lasting 28 days with several pauses along the way, he ultimately reached safety within Germany. Now, his film stands as Germany’s submission for the prestigious Academy Award in the International Feature Film category.

As a cinephile, I can’t help but feel deeply moved when I hear that my film was selected by the German committee. In their own words, they chose to listen to the world, and it’s more than just a decision; it’s a powerful gesture of support for filmmakers like me who create under challenging circumstances.

In “The Seed of the Sacred Fig,” which unfolds against the backdrop of the 2022 protests ignited by Mahsa Amini’s death while in police custody, the oppressive governance of Iran causes a rift within a family due to differing ideologies. When asked by the government for his cooperation as an investigative judge, Iman (Missagh Zareh), a legal professional, is compelled to approve capital punishments. Meanwhile, their two grown daughters, Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami) and Sana (Setareh Maleki), become vocal opponents of the status quo, choosing not to stay quiet in the face of the turmoil they see through social media.

For the past 15 years, Rasoulof has been closely involved with interrogators, censors, the judicial system, and the security forces in Iran. He observed that there were striking similarities among these various groups. What they all seemed to have in common was a willingness to bow to power.

Making his first feature film, “The Twilight” in 2002, served as the spark for Rasoulof’s lifelong dedication to creating dissident art. This movie, a blend of documentary and fiction, depicted a prison inmate who got married while serving his sentence, with real people portraying themselves and reenacting actual events from their lives.

While filming that shoot, Rasoulof stayed for several days in prison alongside his actors, something he never thought would happen to him as a convict later on. He jokes, “I’m probably the only director who’s had such diverse experiences of being incarcerated.” “It’s not just about observing,” he continues, “but actually living it as a prisoner. They are two distinct experiences.

In his late twenties, Rasoulof thought that his work would foster significant discussions at home. “The Twilight” was the only award he ever received in Iran from the prestigious Fajr International Film Festival. Yet as his stories became more directly critical of the system, they were banned from public viewing.

He reflects that he initially believed himself to be a critic who could contribute to improvements by showcasing his perspective through films and inspiring those in power to bring about change. However, as the completion of that film neared, he came to understand how misguided he was, realizing that structural power can be significantly more potent than an individual’s will.

In his 2011 drama “Goodbye,” a line that could reflect Jafar Panahi’s personal feelings might read: “It’s preferable to be an outsider in a far-off place, rather than feeling like a foreigner in your own homeland.

He tells me he doesn’t identify with that impulse.

In Rasoulof’s words, “My daily existence was overflowing with empathy, as I carefully chose the people I interacted with. However, there are many individuals who, due to financial constraints, do not have this privilege. Consequently, their lives are far more brutal.

The Iranian government’s cultivation of distrust among its people is a crucial method they use to retain power. As “Sacred Fig” actor Maleki explains through an interpreter during a Zoom conversation with her co-star Rostami, it serves to divide the population, stifle protest movements, and costs them nothing in return.

Following the protests sparked by Mahsa Amini’s death, both actors—including their director now living in Europe—opted to refuse roles that necessitated wearing Iran’s mandatory hijab. As Maleki states, “If I am to act in just one film throughout my career, it should be something I truly stand behind.

Casting actors to make a film in secret (at the risk of jail time or worse) is no trivial task. The strategies he employs, Rasoulof says, are akin to those employed by drug traffickers. “Of course, we were only smuggling human values,” he says half-jokingly, still amused to be put in that position.

In the realm of filmmaking, I often find myself reaching out to potential collaborators, gauging their interest and resilience with a candid approach: “We’re currently developing a short project that may not adhere to traditional norms. If you decide to join us, be prepared for some creative friction. What are your thoughts on this?” I make it a point to seek out kindred spirits who share my independent spirit, and our interactions serve as a litmus test for that very quality.

Having served time in prison, making me somewhat familiar with the underworld, I can identify people I can approach,” he notes, savoring his position of rebellion.

It’s sweet how he manages to find humor amidst his struggles, according to Rasoulof, who says it’s the only thing that keeps him going.

Even after everyone involved had been thoroughly checked and joined the team, the production remained vigilant. As Rostami remembers, “Before filming began, Setareh and I both studied the script, but due to security concerns, we were forbidden from taking it home with us at any point.

According to Rasoulof, two individuals who later joined the team shared with him their initial suspicion about the film being a government trick to identify those interested in underground cinema. Later, his negotiator expressed doubt towards these same individuals, suggesting we should be cautious about involving them due to potential risks they posed.

Above all else, loyalty mattered most. A person who was loyal, even if they weren’t yet fully skilled, held more worth than an experienced expert whom one couldn’t rely on. Despite having to compromise artistic integrity occasionally, Rasoulof is prepared to make this sacrifice.

He points out that having the ability to circumvent censorship carries its own significance. Essentially, he had two options: one was to abstain from filmmaking altogether as he found it unappealing to create under the control of censors, and the other was to continue making films in this manner.

Rasoulof is confident that his award-winning film will reach Iranian viewers via social media platforms such as Telegram. He advocates for this method, but expresses a preference for how it’s viewed. “I simply ask people to please not watch it on a mobile device,” he says with a smile, “but rather ensure they have a larger screen to enjoy it.

In reference to the latest U.S. presidential elections, Rasoulof expresses that under these circumstances, the public possesses the power to select a period of darkness, provided it’s the majority, no matter how small, who opt for this darkness.

Contrastingly, in Iran, a small group wields significant power over the entire nation, effectively denying the populace the freedom to decide between embracing their own darkness or not.

For Americans, it’s promising that the Trump administration won’t last forever, giving them an opportunity to select better leaders down the line. Conversely, the ability for self-governance and the chance to rectify errors isn’t granted in Iran.

He expresses that the current situation for Iranians can only improve if an external force intervenes, as the Islamic Republic, principally, suppresses its own citizens.

In the midst of an unpredictable phase of his life, where he found himself giving interviews as a fugitive, Rasoulof embraces a fresh sense of routine that was previously unknown to him, drawn from what initially appeared to be trivial matters.

Whenever I stood at the threshold of my home in Iran, ready to step out, I’d pause, take a deep breath, and hesitate with a quiet fear, ‘Could there be people waiting outside to whisk me away?’ Now, as I confidently open my door without such worries, it brings me immense happiness.

That sense of safety, however, comes at a great emotional cost, familiar to anyone who’s been uprooted from a place they once knew. “I adore Iran and its culture,” he says. “That’s the place where I got to know life, where I got to know what humanity means. It’s the window I was granted onto the world.”

In foreign lands, the courageous artists led by Rasoulof find comfort within each other, clinging to optimism for a fresh start in Iran.

In simpler terms, Maleki expresses that for her, “home” now represents the bond of unity and companionship we share as fellow humans, ensuring no one feels isolated. To her, “home” is the comfort of inviting someone over for a cup of tea.

In a world Rasoulof continues to hope for, someday that invitation may bring them back to Iran.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- FC Mobile 26: EA opens voting for its official Team of the Year (TOTY)

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

2024-11-27 22:32