Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research suggests the predictable patterns observed in large language models may stem from fundamental principles of learning, rather than the intricacies of language itself.

This review connects neural scaling laws in transformer models to the behavior of random walks on graphs, revealing a deeper link between model size, learning dynamics, and computational efficiency.

The empirical success of scaling laws in large language models presents a paradox: how can performance be predictably linked to model size without a clear understanding of the underlying mechanisms. This paper, ‘On the origin of neural scaling laws: from random graphs to natural language’, investigates this question by demonstrating that scaling laws emerge even in simplified settings-specifically, learning random walks on graphs-suggesting they aren’t solely dependent on the complexity of natural language data. By systematically varying data complexity and exploring diverse graph structures, the authors reveal a consistent evolution of scaling exponents and offer a critical re-evaluation of established techniques for analyzing and optimizing model training. Do these findings point towards fundamental principles governing learning itself, independent of specific data distributions or architectures?

The Inevitable Trajectory of Scale

Recent progress in deep learning has revealed consistent and predictable relationships between a model’s size, the size of the dataset used for training, and the resulting performance achieved. These observations, formalized as Neural Scaling Laws, indicate that performance improves as either model size or dataset size increases – and often, as both expand concurrently. This isn’t simply a linear progression; rather, the gains follow a power-law relationship, suggesting that substantial increases in scale can yield disproportionately large improvements in capabilities. \text{Performance} \propto \text{Model Size}^\alpha \times \text{Dataset Size}^\beta While intuitively appealing, these laws also highlight the inherent limitations of scaling, as diminishing returns eventually set in, and computational costs become prohibitive. Understanding these dynamics is therefore essential for guiding future research and optimizing resource allocation in the development of increasingly powerful artificial intelligence systems.

Neural scaling laws reveal a compelling, yet nuanced, relationship between model capacity and performance. While consistently increasing the size of a model and the dataset used for training generally yields improvements in capability – demonstrated across various tasks from language processing to image recognition – this progress isn’t limitless. Gains become progressively smaller with each increase in scale, indicating diminishing returns and substantial computational costs. Furthermore, these laws suggest fundamental bottlenecks exist, potentially linked to the inherent complexity of the data or the architecture itself, which prevent indefinite scaling from unlocking unbounded intelligence. Therefore, a thorough understanding of these limitations is critical for guiding efficient resource allocation and for exploring alternative approaches to artificial intelligence beyond simply ‘bigger is better’.

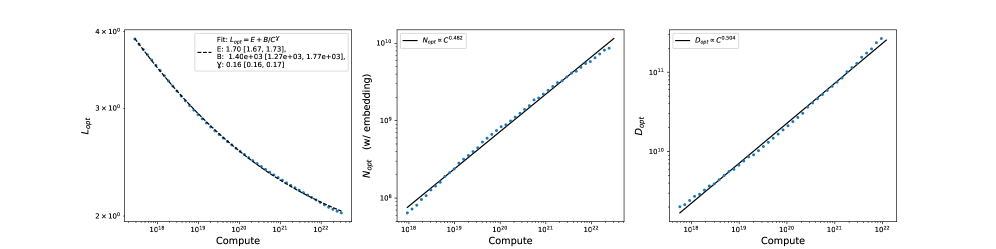

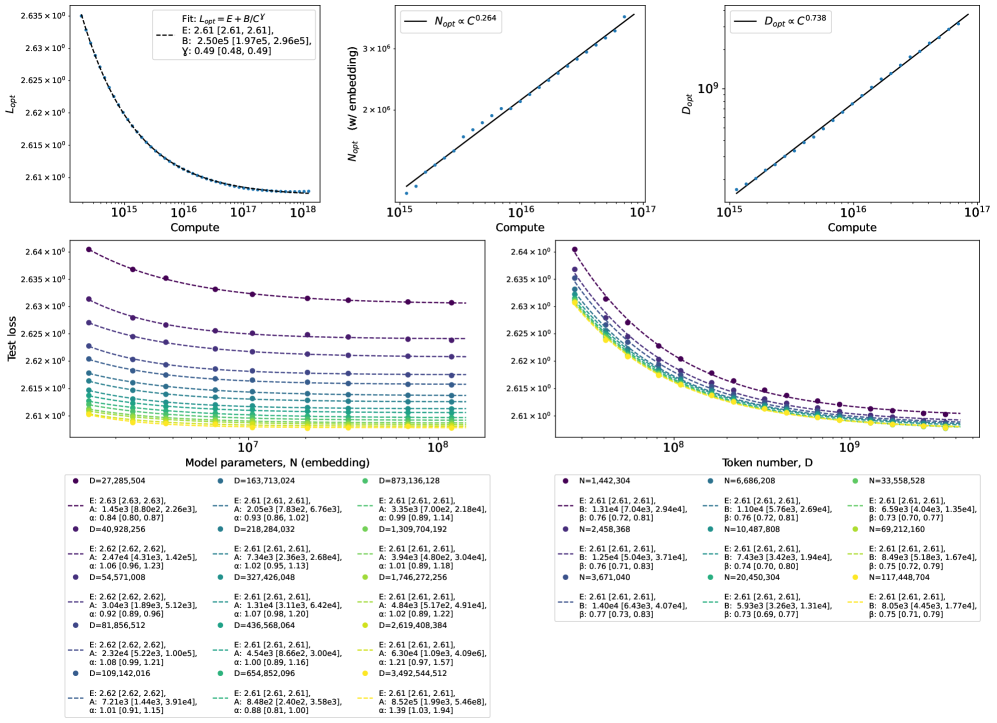

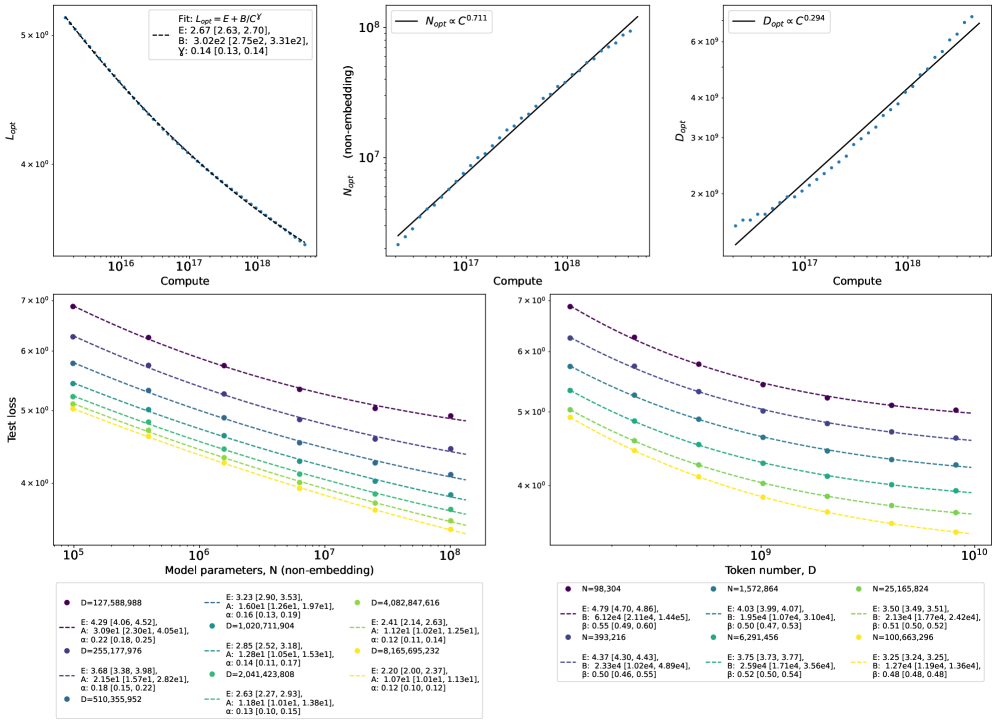

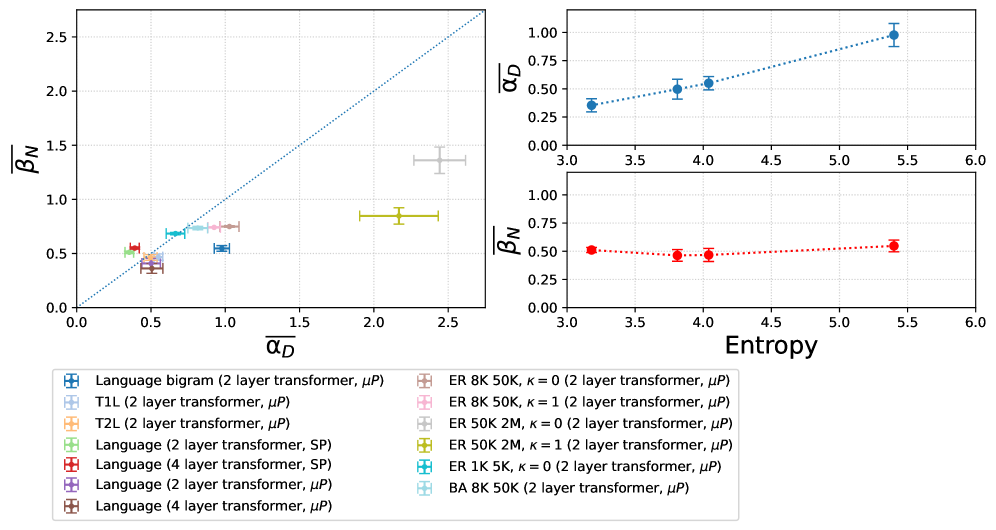

Predictable relationships between model scale and performance have significant implications for the future of artificial intelligence, demanding a careful consideration of resource allocation during model development. Recent investigations reveal that these scaling dynamics – wherein increased model or dataset size leads to improved performance – are observable even within simplified computational settings. Specifically, analysis demonstrates a range of Mean Exponents α (Data) from 0.3 to 2.4, contingent upon the underlying graph type and training parameters utilized. This variability underscores the importance of understanding how these exponents shift across different architectures and datasets, enabling more efficient strategies for optimizing model performance without simply relying on brute-force scaling and potentially wasted computational resources.

Data’s Complexity: The Grain of Reality

Data complexity, referring to the inherent difficulty in learning patterns from a given dataset, directly affects the predictive power of scaling laws. These laws, which describe the relationship between model size, dataset size, and performance, assume a certain level of learnability; datasets with high complexity require substantially larger models and more data to achieve comparable performance to simpler datasets. Specifically, increased data complexity manifests as a deviation from the expected logarithmic improvement in performance with increased model size or dataset size, necessitating adjustments to scaling predictions. The observed performance gap between datasets with differing complexities highlights the importance of characterizing data difficulty to accurately estimate resource requirements and optimize model training strategies.

Robust loss functions address limitations of Mean Squared Error (MSE) when datasets contain outliers or noise. While MSE penalizes all errors equally, exacerbating the impact of anomalous data points, functions like HuberLoss employ a linear cost for large errors, reducing sensitivity to outliers. This characteristic is critical because outliers can disproportionately influence model training, leading to suboptimal performance and reduced generalization. By down-weighting large errors, robust loss functions allow models to focus on the majority of the data, improving stability and accuracy, particularly in real-world datasets which frequently exhibit noise and inconsistencies. The selection of an appropriate loss function is therefore a key consideration during model development and should be tailored to the characteristics of the training data.

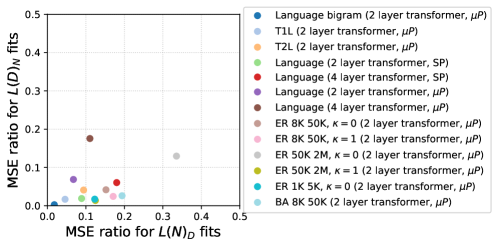

Quantifying data complexity enables more effective model development and optimization strategies. Empirical analysis reveals that power-law scaling consistently outperforms exponential scaling when fitting data complexity metrics. Specifically, the Mean Squared Error (MSE) ratio comparing power-law to exponential fits is between 50x and 100x better for datasets characterized by L(D)N – where L represents dataset size, D represents data dimensionality, and N represents the number of parameters – and between 5x and 10x better for datasets characterized by L(N)D. These results indicate that power-law models provide a significantly improved fit for characterizing the relationship between dataset size, dimensionality, and model parameters, suggesting their utility in predicting model performance and guiding model design choices.

Efficient Updates: Resisting the Entropy of Computation

StandardParameterization, a common approach to updating model weights during training, scales poorly with model size due to its reliance on storing and updating a parameter vector for each individual weight. As the number of parameters N increases – characteristic of modern large language models – the computational cost of each update step grows linearly with N. This is because each parameter requires its own gradient calculation and subsequent application of the optimization algorithm. Furthermore, the memory footprint required to store these parameters and their associated gradients also increases proportionally, creating both computational and memory bottlenecks during training. This inefficiency stems from the direct association of each parameter with a corresponding entry in the optimization state, limiting the potential for parameter sharing or compression.

MaximalUpdateParameterization (MUP) aims to improve training efficiency by decoupling the parameter update from the optimization step; instead of directly updating model parameters w, MUP introduces a separate update vector \Delta w that is optimized, and the parameters are then updated as w = w + \Delta w. This approach allows for the optimization of \Delta w with a potentially lower computational cost, especially when combined with techniques like low-rank factorization or sparsity constraints applied to \Delta w. By focusing optimization on the update vector, MUP can reduce the number of operations required per training step, particularly in large models where direct parameter updates become a bottleneck. The method enables the use of different optimization strategies for \Delta w than those used for the original parameters, offering further opportunities for efficiency gains.

Combining efficient parameterization schemes, such as MaximalUpdateParameterization, with Parameter Efficient Training (PET) techniques yields substantial computational cost reductions. PET methods, including techniques like LoRA and adapters, limit the number of trainable parameters during fine-tuning, while efficient parameterization optimizes how those parameters are updated. This synergistic effect minimizes both memory requirements and the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) needed per training step. The resulting decrease in computational load allows for training larger models with limited hardware resources, or accelerates the training process for existing models without increasing resource demands. Specifically, by reducing the number of parameters requiring gradient calculation and storage, and by streamlining the parameter update process, these combined approaches can achieve significant speedups and resource savings during model training and fine-tuning.

Statistical Rigor: Accounting for the Imperfections of Measurement

Statistical estimates, derived from sample data, are inherently susceptible to bias due to factors such as selection bias, measurement error, and confounding variables. This bias manifests as a systematic deviation of the estimated value from the true population parameter, potentially leading to over- or under-estimation. For example, a biased sample may not accurately represent the population, causing inferences drawn from that sample to be inaccurate. Consequently, biased estimates can distort research findings, invalidate conclusions, and impede the reliable prediction of outcomes; therefore, acknowledging and addressing potential sources of bias is crucial for ensuring the validity and integrity of statistical analyses.

Bias correction techniques, notably bootstrapping, are critical for refining statistical estimates by reducing systematic error and quantifying uncertainty. Bootstrapping involves resampling with replacement from the original dataset to create multiple simulated datasets; statistical estimates are then calculated for each resampled dataset, generating a sampling distribution. The standard error of the estimate can be derived from this distribution, providing a measure of the estimate’s precision. Furthermore, confidence intervals can be constructed to assess the range within which the true population parameter likely falls. Applying bootstrapping, or similar methods like jackknifing, is particularly important when dealing with complex models or limited data, as these scenarios are prone to biased estimates and unreliable inferences.

Application of bias correction techniques to neural scaling laws is critical for ensuring the derived findings are robust to variations in datasets and model architectures. Specifically, these methods quantify the uncertainty associated with parameter estimates, enabling assessment of whether observed relationships – such as power-law scaling – hold consistently across different experimental conditions. Without such correction, estimated scaling exponents and associated predictive performance may be overly optimistic or specific to the training data, limiting the generalizability of the laws to unseen models or datasets. Validating the consistency of these laws through bias-corrected analysis increases confidence in their predictive power and facilitates more reliable extrapolation to larger model sizes or different data distributions.

The Next Generation: Architectures Adapting to the Constraints of Reality

The Transformer architecture has rapidly become fundamental to modern language modeling due to its inherent ability to capitalize on established scaling laws. These laws dictate that performance improvements aren’t simply linear with increased model size or data quantity, but follow a power-law relationship – meaning even modest increases in scale can yield disproportionately large gains. The Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, allowing it to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence, is particularly well-suited to exploit this phenomenon. By strategically increasing model parameters and training data, researchers have consistently demonstrated improved performance on a wide range of natural language processing tasks. This optimization isn’t merely about ‘bigger is better’; it’s about understanding and leveraging the predictable relationship between scale and capability, driving advancements in areas like text generation, translation, and question answering.

At the heart of modern language model training lies the deceptively simple task of next token prediction – essentially, forecasting the most probable subsequent word in a sequence. This process isn’t achieved through guesswork, but via a rigorous mathematical framework centered around CrossEntropyLoss. This loss function quantifies the difference between the model’s predicted probability distribution over possible next tokens and the actual, observed token. By minimizing this difference through iterative adjustments to the model’s parameters, the system learns to assign higher probabilities to correct predictions. The effectiveness of CrossEntropyLoss stems from its ability to penalize confidently incorrect predictions more severely than hesitant, yet ultimately accurate, ones, driving the model towards increasingly refined statistical representations of language. Consequently, the accuracy of next token prediction, as measured by reductions in CrossEntropyLoss, directly correlates with the overall performance and fluency of the resulting language model.

Achieving the full potential of large language models hinges on a trifecta of optimization: data complexity, parameter efficiency, and statistical rigor. Recent analyses demonstrate that model performance isn’t simply a matter of increasing scale, but rather intelligently managing these interconnected factors. Specifically, the Mean Exponent β, a key indicator of model capacity, was observed to range from 0.7 to 1.4 across various models and datasets. This suggests that optimal scaling strategies aren’t linear; a nuanced approach is required, carefully balancing the complexity of the training data with the number of model parameters to maximize performance gains and avoid diminishing returns. Understanding this exponent provides a crucial metric for guiding the development of next-generation language models, allowing researchers to move beyond brute-force scaling and towards more efficient and statistically sound architectures.

The observed consistency of scaling laws across varied systems-from the complex architecture of transformer models to the simplicity of Markov random walks-reveals a fundamental principle at play. It suggests that learning isn’t merely about processing data, but about navigating inherent structural properties. This echoes a sentiment expressed by Vinton Cerf: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” While seemingly paradoxical, this applies here-the ‘magic’ of emergent abilities in large language models isn’t arising from complex data alone, but from the predictable patterns emerging as systems scale, mirroring the underlying logic found even in random graphs. The arrow of time, in this context, points toward an inevitable refinement of these laws as computational resources continue to expand.

The Long View

This work establishes a compelling, if unsettling, parallel. If the emergent scaling laws governing large language models are echoed in the behavior of random walks on graphs, then the chronicle of their development shifts. Logging is no longer simply a record of training on increasingly vast corpora; it becomes a tracing of a fundamental process unfolding, regardless of the substrate. The question then isn’t what these models learn, but how learning itself imposes constraints, creating patterns irrespective of the data’s initial complexity.

Deployment, considered as a moment on the timeline, reveals the limitations of current investigation. The field tends to treat model size as a lever, and dataset size as fuel. But if these laws are intrinsic, optimizing compute may only refine the inevitable. A critical, unresolved problem is identifying the minimal conditions-the barest graph, the simplest walk-that still manifest these scaling relationships. Understanding those foundations may offer a route to graceful decay, a way to anticipate and mitigate the inherent limitations of any learning system.

The study’s implications extend beyond language. Sequence modeling, in its various forms, operates under similar pressures – the tension between complexity and generalization. Future work should explore whether these observed laws are a universal artifact of iterative processes, a consequence of systems navigating state spaces, irrespective of their apparent purpose. The true measure of progress may not be achieving ever-larger models, but acknowledging the boundaries inherent in any attempt to map the infinite.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10684.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

2026-01-19 00:51