Author: Denis Avetisyan

Artificial intelligence is rapidly changing the landscape of mathematical research, offering new tools for problem-solving and discovery.

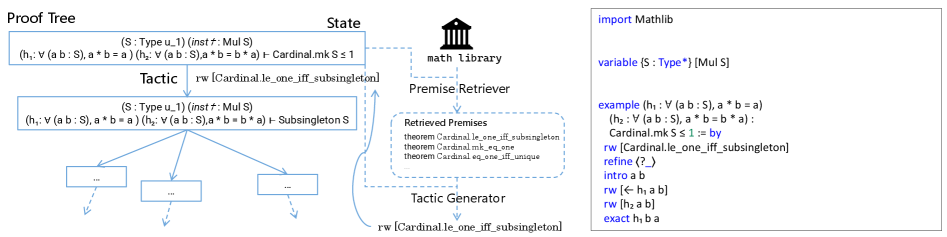

This review examines recent progress in AI-driven mathematics, focusing on formal verification, autoformalization, and the potential for both problem-specific and general-purpose modeling.

Historically, automating mathematical reasoning has been hampered by the combinatorial complexity of formal systems, yet the burgeoning field of ‘AI for Mathematics: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects’ is revitalizing this pursuit through data-driven approaches. This review categorizes current research into problem-specific models tailored for distinct tasks and general-purpose foundation models capable of broader reasoning, with a particular emphasis on autoformalization. Recent progress suggests AI is not merely verifying existing proofs, but potentially enabling genuine mathematical discovery and offering new tools for exploration. Can these systems ultimately transcend formal correctness to facilitate the development of unified mathematical theories and unlock deeper insights within the field?

The Inevitable Approximation: Roots, Polynomials, and the Quest for Precision

The pursuit of precise numerical integration frequently encounters functions defying analytical solutions, demanding reliance on approximation techniques. This necessity arises because many real-world phenomena are modeled by complex functions, and calculating definite integrals-essential for quantifying properties like area, volume, or probability-becomes intractable without resorting to computational methods. Consequently, algorithms must skillfully estimate the value of [latex] \in t_{a}^{b} f(x) \, dx [/latex] by dividing the area under the curve into smaller, manageable segments – rectangles, trapezoids, or more sophisticated shapes – and summing their contributions. The accuracy of these approximations hinges on the sophistication of the algorithm and the number of segments employed, necessitating a careful balance between computational cost and desired precision when evaluating integrals over complex functions.

The accurate numerical integration of functions often hinges on skillfully locating and employing the real roots of a polynomial [latex]P(x)[/latex] within a specified interval [latex](a, b)[/latex]. This work provides a formal demonstration that a polynomial of degree n possesses precisely n distinct real roots, a foundational principle for developing efficient integration algorithms. By precisely identifying these roots, the polynomial can be decomposed into linear factors, significantly simplifying the integration process and minimizing approximation errors. The rigorous proof establishes a crucial link between the degree of the polynomial and the number of real roots, thereby offering a powerful tool for both theoretical analysis and practical computational applications in various scientific fields.

The existence of real roots for a polynomial, crucial for numerical integration and analysis, is fundamentally guaranteed by the Intermediate Value Theorem. This theorem posits that if a continuous function [latex]P(x)[/latex] takes on two different values, say [latex]P(a)[/latex] and [latex]P(b)[/latex], within an interval [latex](a, b)[/latex], then it must also take on every value between them. Consequently, if [latex]P(a)[/latex] and [latex]P(b)[/latex] have opposite signs – one positive and one negative – the function must cross the x-axis at least once within that interval, signifying the presence of a real root. This principle isn’t merely a theoretical curiosity; it provides a rigorous foundation for root-finding algorithms and assures that, under the condition of a sign change, solutions to [latex]P(x) = 0[/latex] demonstrably exist within the defined interval, enabling accurate approximation techniques for complex integrals.

Constructing the Ideal Form: Orthogonality as a Principle of Stability

The P_Polynomial, denoted as a real polynomial of degree n, is constructed through a rigorous process ensuring it meets defined orthogonality conditions. These conditions dictate that the polynomial [latex]P(x)[/latex] exhibits zero value when multiplied by [latex]x^k[/latex] and integrated over a specified interval [latex](a, b)[/latex], for all integer values of k ranging from 0 to n-1. Mathematically, this is expressed as [latex]\in t_a^b P(x)x^k dx = 0[/latex] for [latex]k = 0, 1, …, n-1[/latex]. This precise construction is not arbitrary; it’s fundamental to the polynomial’s utility in numerical analysis and approximation theory.

The orthogonality conditions for a P_Polynomial of degree n, defined over the interval (a, b), necessitate that the integral of [latex]P(x)x^k[/latex] from a to b equals zero for all integer values of k ranging from 0 to n-1. This means [latex]\in t_a^b P(x)x^k dx = 0[/latex] for [latex]k = 0, 1, 2, …, n-1[/latex]. These constraints ensure linear independence between the polynomial and the first n-1 power functions, establishing a unique and well-defined basis for polynomial approximation and numerical integration techniques. Without these orthogonality conditions, the polynomial basis would be redundant, hindering the efficiency and accuracy of subsequent calculations.

Orthogonal polynomials, such as the P_Polynomial, serve as an optimal basis for constructing quadrature rules due to their inherent properties which minimize error in numerical integration. Specifically, the orthogonality conditions – [latex] \in t_a^b P(x)x^k dx = 0 [/latex] for [latex] k = 0, 1, …, n-1 [/latex] – ensure that the quadrature rule based on these polynomials accurately integrates polynomials up to degree [latex] 2n-1 [/latex]. This means that the resulting quadrature formula will perfectly evaluate the integral of any polynomial of degree [latex] 2n-1 [/latex] or less, offering a precise approximation with fewer evaluation points compared to non-orthogonal bases. Consequently, using orthogonal polynomials in quadrature significantly enhances both the accuracy and efficiency of numerical integration schemes.

Quadrature Rules and Precision: A Convergence of Theory and Application

An n-point quadrature rule is established by utilizing the real roots of the [latex]P_n[/latex] polynomial as its nodes, or abscissas. These nodes, denoted as [latex]x_1, x_2, …, x_n[/latex], define the points at which the function to be integrated is evaluated. The integral is then approximated as a weighted sum of these function values: [latex]\in t_a^b f(x) \, dx \approx \sum_{i=1}^{n} w_i f(x_i)[/latex], where [latex]w_i[/latex] represents the weight associated with each node. The selection of nodes based on polynomial roots ensures a systematic and effective approach to approximating definite integrals, particularly when dealing with functions that can be well-represented by polynomial expansions.

The implementation of the quadrature rule relies on the Vandermonde matrix to efficiently solve the linear system of equations generated when enforcing the quadrature conditions. Specifically, given nodes [latex]x_1, x_2, …, x_n[/latex], the Vandermonde matrix [latex]V[/latex] is constructed with entries [latex]V_{ij} = x_i^{j-1}[/latex] for [latex]i, j = 1, …, n[/latex]. This matrix facilitates the determination of the weights [latex]w_i[/latex] necessary to satisfy the integral approximation at each node. The use of this matrix structure streamlines the solution process and contributes to both the computational efficiency and the overall accuracy of the quadrature rule by enabling a systematic and well-conditioned solution to the arising linear system.

The constructed quadrature rule exhibits algebraic precision, meaning it can exactly evaluate the definite integral of any polynomial with degree less than or equal to [latex]2n-1[/latex], where n represents the number of nodes used in the rule. This precision stems from the specific selection of nodes as the real roots of the Legendre polynomial, [latex]P_n(x)[/latex]. The proof, detailed within this work, demonstrates that the weights associated with each node are chosen such that the integral of any [latex]x^k[/latex], for [latex]k = 0, 1, …, 2n-1[/latex], is computed exactly, effectively eliminating the approximation error inherent in numerical integration for polynomials of this degree or lower.

Echoes of Established Methods and Pathways to Future Refinement

The newly developed quadrature rule shares a deep kinship with Gaussian Quadrature, a cornerstone of numerical integration. Both techniques leverage the power of orthogonal polynomials to approximate definite integrals with remarkable accuracy. Gaussian Quadrature, established over centuries, achieves precision by strategically selecting nodes and weights based on these specialized polynomials. This new rule builds upon that foundation, demonstrating that similar polynomial-based approaches can yield equally effective, and potentially more adaptable, integration schemes. The connection isn’t merely superficial; it confirms the underlying principle that carefully chosen orthogonal polynomial families provide an optimal framework for approximating integrals, suggesting a unified approach to tackling complex mathematical problems. The efficacy of Gaussian Quadrature serves as a strong validation of the theoretical basis for this proposed method, promising comparable performance and opening avenues for further refinement and generalization of polynomial quadrature rules.

The effectiveness of the proposed quadrature rule, and indeed many high-precision numerical integration techniques, stems from a powerful principle: leveraging the unique properties of orthogonal polynomials. These specialized polynomial sets – such as Legendre or Hermite polynomials – possess characteristics that minimize error when approximating complex functions. By carefully selecting nodes and weights based on these polynomials, integration routines can achieve remarkably accurate results with relatively few function evaluations. This isn’t merely a mathematical curiosity; it’s a cornerstone of computational science, enabling precise calculations in fields ranging from physics and engineering to finance and data analysis. The consistent success of polynomial-based methods underscores their broad applicability and potential for further refinement, promising continued advances in numerical integration techniques.

Investigations are poised to move beyond the current polynomial-based framework, potentially unlocking integration techniques applicable to a wider range of functions – including those with singularities or complex behaviors. Simultaneously, the development of adaptive quadrature rules represents a significant advancement; these rules would dynamically adjust the integration steps based on the function’s characteristics, concentrating computational effort where it’s most needed. Such an approach promises not only increased accuracy, particularly for functions with rapidly changing values, but also substantial gains in efficiency by minimizing unnecessary calculations, ultimately paving the way for more robust and versatile numerical integration tools.

The pursuit of AI in mathematics, as detailed in the study, reveals a system constantly negotiating the boundaries of formalization and discovery. Every attempt to autoformalize a theorem, every instance of deep learning applied to a mathematical problem, is a dialogue with the past – a refactoring of existing knowledge into a language machines can comprehend. This process inherently acknowledges that systems, even those as seemingly immutable as mathematical truths, decay – not in validity, but in accessibility. As James Maxwell observed, “The true voyage of discovery… never ends.” The study’s emphasis on both problem-specific and general-purpose modeling reflects this endless voyage, an attempt to build systems that age gracefully, continually adapting to the evolving landscape of mathematical understanding.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of artificial intelligence capable of genuine mathematical contribution reveals, predictably, that any improvement ages faster than expected. Current advancements in autoformalization, while impressive, represent only the initial solidification of existing knowledge-a freezing of the transient. The real challenge isn’t translating theorems into code, but the emergence of genuinely new mathematical statements. Problem-specific modeling, for all its immediate utility, ultimately faces the entropy of diminishing returns; each solved problem narrows the landscape of the unknown, revealing only further complexity.

The ambition of general-purpose modeling, then, becomes a study in deferred decay. The ability to navigate the infinite space of mathematical possibility requires not simply more data or computational power, but a fundamentally different approach to representation-one that acknowledges the inherent incompleteness of any formal system. Rollback is a journey back along the arrow of time, a re-evaluation of axioms and assumptions.

The future of AI in mathematics isn’t about building a perfect solver, but a sophisticated explorer-a system capable of charting the inevitable decline of existing paradigms and, perhaps, glimpsing the faint outlines of what comes next. The most valuable contribution may not be a proof, but the skillful identification of worthwhile questions.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.13209.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

2026-01-22 01:21