Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study reveals that the software bringing robot designs to life often falls short of theoretical ideals, impacting performance and reliability.

Empirical analysis of robot control software implementations highlights discrepancies between control theory and practical engineering, particularly in discretization, safety mechanisms, and verification procedures.

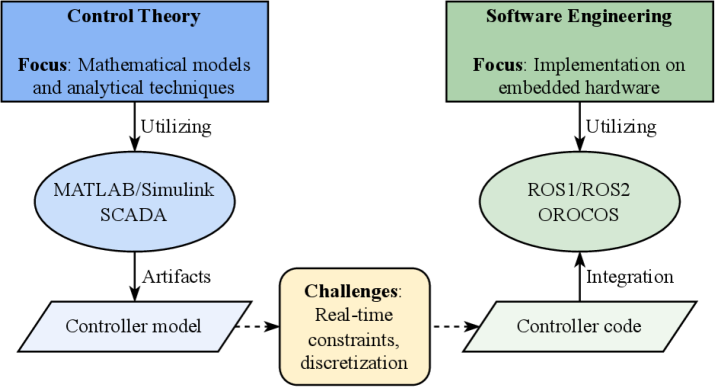

While control theory provides robust designs for robotic systems, a disconnect often exists between theoretical guarantees and practical software implementation. This is explored in ‘Beyond the Control Equations: An Artifact Study of Implementation Quality in Robot Control Software’, an empirical investigation of 184 open-source robot controller implementations. Our analysis reveals widespread ad-hoc approaches to discretization, insufficient error handling, and a notable lack of systematic verification-raising concerns about real-time reliability and safety. How can we bridge this gap and establish rigorous implementation guidelines to ensure the dependable performance of increasingly complex robotic systems?

The Inevitable Loop: Control Systems as Robotic Nervous Systems

The success of modern robotics isn’t simply about powerful motors or intricate mechanics; it fundamentally depends on robust control systems. These systems act as the robotic brain, constantly monitoring the robot’s state and adjusting its actions to achieve desired movements and maintain stability even when faced with disturbances or uncertainties. Consider a robotic arm assembling electronics – without precise control, it would be prone to jerky motions, inaccurate placements, and potential damage. Sophisticated algorithms, informed by decades of control theory research, enable robots to compensate for friction, varying loads, and unexpected external forces. This capability is crucial not only for industrial automation, where repetitive precision is paramount, but also for increasingly complex applications like surgical robotics, autonomous vehicles, and exploration in unpredictable environments. The ongoing development of more adaptable and resilient control systems remains a central challenge in realizing the full potential of robotics.

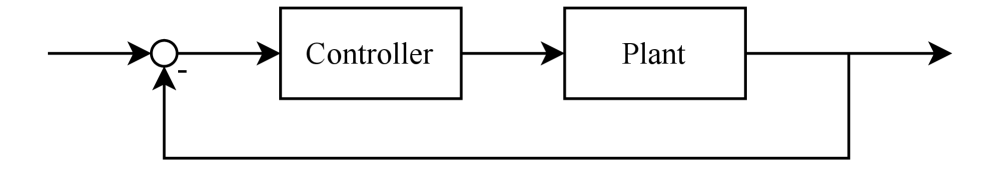

Robotic control systems aren’t simply assembled; they are designed upon a solid foundation of Control Theory, a branch of engineering mathematics dedicated to understanding and manipulating system behavior. This theoretical framework provides the tools to analyze a robot’s response to commands, predict its stability – whether it will smoothly reach a desired position or oscillate uncontrollably – and optimize its performance. Concepts like feedback loops, where sensor data informs adjustments to movement, and mathematical models describing a robot’s dynamics, are central to achieving precise and reliable operation. [latex]u(t) = K_p e(t) + K_i \in t e(t) dt + K_d \frac{de(t)}{dt}[/latex] – a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controller, for example – exemplifies how Control Theory translates into practical algorithms enabling robots to maintain balance, navigate complex environments, and execute intricate tasks with accuracy. Without this rigorous theoretical underpinning, robotic movements would be unpredictable and prone to failure.

The Robot Controller functions as the central nervous system of any robotic system, translating abstract, high-level directives – such as “navigate to location X” or “grasp the object” – into concrete signals for motors, actuators, and sensors. This software component doesn’t simply relay commands; it manages the complexities of robotic motion, incorporating feedback from sensors to maintain stability and accuracy. It continuously monitors the robot’s state, calculates necessary adjustments, and compensates for external disturbances or internal errors. Essentially, the controller closes the loop between desired behavior and physical execution, ensuring the robot responds predictably and reliably to its environment. Without this crucial intermediary, a robot would be incapable of performing even the simplest tasks with any degree of precision or autonomy.

The Discrete Pulse: Time and the Limits of Computation

Robot controllers utilize discrete-time implementations due to the limitations of digital computation and sensor data acquisition. Continuous-time dynamic models, commonly used in control system design, must be converted into discrete-time equivalents through techniques like forward or backward Euler, Tustin’s method, or zero-order hold discretization. The selection of a suitable discretization method impacts the accuracy and stability of the resulting digital controller. Crucially, the sampling rate [latex]T_s[/latex] – the reciprocal of the sampling frequency – dictates the time interval between controller updates and sensor readings. An insufficiently small [latex]T_s[/latex] can lead to aliasing and instability, while an excessively small value increases computational load. The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem guides the minimum sampling rate required to accurately represent a continuous signal, typically requiring a sampling frequency at least twice the highest frequency component of the signal being controlled.

Real-time execution in robot control systems necessitates that all control loop iterations, including sensing, computation, and actuation, complete within a predefined and consistent time interval. Failure to meet these timing constraints can introduce delays that destabilize the system, potentially leading to oscillations or complete loss of control. The maximum allowable loop execution time is determined by the system’s dynamics and is often significantly shorter than the sampling period to ensure adequate margin for computational overhead and unpredictable delays. Deterministic execution – where the time required for each iteration is consistently bounded – is crucial, and systems are frequently designed with worst-case execution time (WCET) analysis to guarantee stability under all operating conditions. Violations of these real-time constraints can result in performance degradation or, critically, catastrophic system failure.

The internal clock within a robot controller functions as the central timing source for all control loop operations. This clock generates periodic interrupts that trigger the execution of control algorithms, ensuring consistent and predictable timing for tasks such as sensor data acquisition, state estimation, and actuator commands. The frequency of the internal clock – often expressed in Hertz (Hz) – directly dictates the control loop’s sampling rate and, consequently, its ability to accurately represent and respond to dynamic system behavior. Precise clock accuracy and stability are critical; deviations can introduce timing jitter, leading to performance degradation or instability. Synchronization of all controller components to this single timing reference is essential for coordinated operation and reliable system performance.

Derivative filtering is a common practice in robot control systems to mitigate the impact of measurement noise on calculated derivatives. Direct differentiation of noisy signals amplifies high-frequency components, leading to inaccurate and potentially unstable control actions. Filtering, typically employing a low-pass filter such as a moving average or a first-order filter, attenuates these high-frequency noise components before the derivative is computed. The filter’s cutoff frequency is a critical parameter, balancing noise reduction with the preservation of relevant dynamic signals. A common implementation utilizes a digital first-order filter with a transfer function of [latex] \frac{K}{1 + Ts} [/latex], where K is a gain and T is the sampling period. Careful selection of the filter parameters is crucial to avoid introducing excessive phase lag, which can negatively affect control loop stability.

Algorithms and Locomotion: The Shape of Movement

Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) controllers are extensively implemented in robotics due to their relative simplicity in design and tuning, alongside demonstrated effectiveness across a broad range of control tasks. These controllers function by minimizing the error between a desired setpoint and the measured process variable. However, Model Predictive Control (MPC) is increasingly being adopted, particularly in applications demanding higher performance or operating under constraints. MPC utilizes a dynamic model of the system to predict future behavior and optimizes control actions over a prediction horizon, allowing for the explicit handling of constraints and improved tracking performance, though at the cost of increased computational complexity and model identification requirements.

Feed Forward Control operates by calculating control actions directly from the desired setpoint or input, without waiting for feedback from the system. This approach relies on an accurate system model to predict the necessary control signals to achieve the desired output. Unlike feedback control, which corrects errors after they occur, feed forward control proactively anticipates disturbances and adjusts the control signals accordingly. The calculated control action is often summed with the output of a feedback controller, providing a combined control strategy that leverages the strengths of both methods – feed forward’s ability to anticipate and mitigate disturbances, and feedback’s ability to correct for modeling errors and unpredicted disturbances.

Differential drive utilizes two independently controlled wheels, typically on a two-wheeled platform, to achieve locomotion through varying the relative speeds of each wheel; this method is favored in mobile robotics due to its simplicity and maneuverability in constrained spaces. Conversely, Ackermann steering, commonly found in automobiles, employs a geometric linkage that angles the steered wheels to minimize tire scrub during turns; this configuration prioritizes stability and efficiency at higher speeds and is optimized for larger vehicles operating on structured surfaces. While both methods facilitate vehicle control, their distinct mechanical principles and performance characteristics render them suitable for different robotic and automotive applications.

Cartesian controllers are fundamental to robotic arm manipulation due to their ability to directly regulate position and orientation in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. These controllers operate by calculating joint torques or velocities required to achieve a desired end-effector pose, typically expressed as [latex] (x, y, z, \phi, \theta, \psi) [/latex], where the first three terms represent linear position and the latter three represent Euler angles defining orientation. Implementation often involves inverse kinematics to map desired Cartesian coordinates to corresponding joint angles, and Jacobian matrices are employed to relate joint velocities to end-effector velocities, enabling precise trajectory tracking and force control. Advanced Cartesian controllers may incorporate dynamics and friction compensation to improve accuracy and robustness.

Validation and the Illusion of Control

Code-based testing, encompassing both unit and integration tests, is a fundamental practice in verifying robotic controller functionality. Unit tests isolate and validate the behavior of individual software components, such as specific functions or classes, ensuring they operate as designed. Integration tests then assess the interactions between these components, confirming data is correctly passed and processed across the system. This approach allows developers to identify and rectify errors early in the development cycle, improving code quality and reducing the risk of failures during deployment. While offering a high degree of confidence in component correctness, code-based testing requires careful test case design to achieve adequate coverage and may not fully capture the complexities of real-world interactions with hardware.

Simulation-Based Testing offers a practical approach to robotic controller evaluation by allowing for performance assessment under a wide range of scenarios without the risks and expenses associated with physical hardware testing. This method leverages software-based models of the robot, its environment, and sensors to replicate real-world conditions, enabling developers to identify and address potential issues early in the development cycle. The ability to rapidly iterate on designs and test edge cases, such as sensor failures or unexpected environmental disturbances, contributes to improved robustness and reliability. Furthermore, simulation eliminates the potential for damage to physical hardware and reduces the need for costly field testing, making it an economically advantageous strategy for controller validation.

A review of 141 robotic controller implementations built using the Robot Operating System (ROS) indicates a significant preference for simulation-based testing methodologies. Specifically, 78 implementations, representing 64% of the total, incorporate simulation testing. In contrast, only 25 (18%) of the analyzed controllers utilize code-based testing methods such as unit or integration tests. This disparity suggests that developers commonly prioritize evaluating controller functionality within a simulated environment over direct code verification in the studied implementations.

Effective validation and testing of robotic controllers necessitates a robust interface capable of interacting with both simulated environments and physical hardware. This interface serves as the conduit for transmitting commands to the controller and receiving sensor data, enabling verification of performance across a spectrum of operating conditions. The controller’s architecture must accommodate abstraction layers that facilitate seamless transitions between simulation and real-world execution without requiring substantial code modification. Furthermore, the consistency of data formats and communication protocols is critical; discrepancies between simulated and real hardware interfaces can introduce errors and invalidate test results. Consequently, the design of the robot controller directly impacts the feasibility and accuracy of both code-based and simulation-based testing procedures.

The study illuminates a familiar pattern: the chasm between elegant theory and messy implementation. Control engineers craft designs predicated on continuous mathematics, yet these designs invariably yield to the constraints of discrete software. The artifact analysis reveals that discretization-a necessary evil-introduces approximations and potential instabilities often overlooked in the initial design phase. This echoes a sentiment articulated by John von Neumann: “There is no possibility of absolute certainty.” The pursuit of perfect control, as envisioned in the control equations, is ultimately an asymptotic approach. Safeguards and systematic verification, though crucial, are merely attempts to mitigate the inevitable deviations-temporary bulwarks against the encroaching tide of real-world complexity. Each line of code, therefore, isn’t a step toward mastery, but an acknowledgment of inherent uncertainty.

The Seeds of What Comes Next

The study of these robot controller implementations reveals not a failure of control theory, but a reckoning. Equations describe desired behaviors; software becomes behavior, and the becoming is always messy. Each discretization, each safeguard hastily added after a near collision, is a compromise-a prayer offered to the gods of real-time execution. The gap identified isn’t one to be bridged with better tools, but acknowledged as inherent. These systems don’t simply receive logic; they accumulate history, bearing the weight of every patched vulnerability and pragmatic shortcut.

Future work will not center on verification – that’s merely accounting after the fact. Instead, attention must turn to the cultivation of robustness as an emergent property. To treat robot control software as a garden, not a factory. One anticipates a shift from formal methods seeking absolute correctness to observational studies of how controllers actually fail, and how gracefully they degrade. The challenge lies in accepting that instability isn’t a bug, but a sign of growth.

The true frontier isn’t about building better controllers, but understanding how to listen to the whispers of a complex system as it unfolds. Every refactor begins as a prayer and ends in repentance. The art will be in learning to anticipate the shape of that repentance, before the clouds fall again.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04799.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Show Time Worldwide Selection Contract: Best player to choose and Tier List

- Free Fire Beat Carnival event goes live with DJ Alok collab, rewards, themed battlefield changes, and more

- Brent Oil Forecast

2026-02-06 06:48