Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have unveiled a new testing ground for evaluating the potential of machine learning to accelerate the discovery of novel materials.

This work introduces MADE, a benchmark environment demonstrating the importance of adaptive planning and agentic systems for efficient closed-loop materials discovery as search spaces expand.

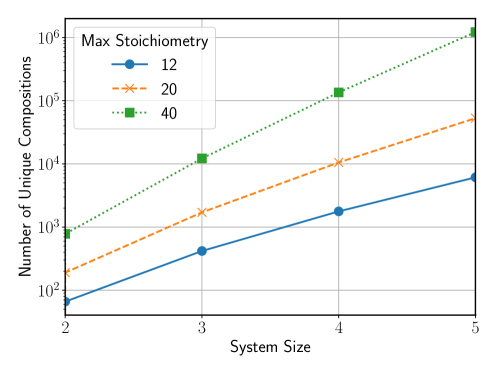

Existing benchmarks for computational materials discovery largely assess static prediction or isolated tasks, neglecting the iterative and adaptive nature of scientific workflows. To address this, we introduce MADE: Benchmark Environments for Closed-Loop Materials Discovery, a novel framework for evaluating end-to-end autonomous materials discovery pipelines that simulates closed-loop campaigns searching for thermodynamically stable compounds. Our results demonstrate that adaptive planning and agentic systems become increasingly crucial for efficient discovery as search spaces expand and the reliability of surrogate models diminishes. Will these environments accelerate the development of fully autonomous materials design systems capable of tackling increasingly complex challenges?

Uncharted Territories: The Slow Dance of Materials Discovery

The development of new materials, historically, has been a painstakingly slow process, often resembling a methodical search through an immense and largely uncharted territory. Researchers traditionally synthesize and test materials one by one, a cycle demanding significant time, financial investment, and physical resources. This ‘trial-and-error’ approach, while foundational to many breakthroughs, faces inherent limitations when confronted with the sheer breadth of possible material combinations – a landscape known as ‘chemical space’. Each experiment carries the risk of failure, and the iterative nature of refinement means that even incremental progress can require substantial repetition. Consequently, the pace of materials innovation has often lagged behind the demands of emerging technologies, highlighting the urgent need for more efficient and predictive discovery methods.

The sheer scale of potential materials-often termed ‘Chemical Space’-presents an immense challenge to researchers. This space encompasses countless combinations of elements and molecular arrangements, numbering in the order of 1060 or more. Conventional computational methods, reliant on calculating the properties of each material individually, quickly become overwhelmed by this complexity. Even with powerful supercomputers, exhaustively screening such a vast landscape is practically impossible, requiring computational resources that far exceed current capabilities. The problem isn’t simply one of processing power; many calculations necessitate intricate quantum mechanical simulations, further increasing the time and energy demands. Consequently, a significant portion of potentially groundbreaking materials remains unexplored, hindering advancements in fields ranging from energy storage to advanced manufacturing.

The pursuit of novel materials hinges on pinpointing compounds possessing inherent stability, a property directly correlated with their minimum formation energy – the energetic change when constituent elements combine. However, calculating these energies accurately across the immense landscape of potential materials presents a significant computational bottleneck. Traditional methods, often reliant on density functional theory, struggle with the complexity of electron interactions, leading to inaccuracies and necessitating extensive, and often fruitless, searches. This challenge is compounded by the fact that even seemingly minor errors in energy calculations can incorrectly classify unstable compounds as viable, or vice-versa, drastically hindering materials discovery efforts. Consequently, researchers are actively developing more efficient algorithms and incorporating machine learning techniques to predict stability with greater speed and reliability, effectively narrowing the search space and accelerating the identification of promising new materials.

Closing the Loop: An Iterative Dance with Discovery

Closed-Loop Discovery operates on a cyclical process analogous to the scientific method. Initially, the system proposes potential candidate materials based on predefined criteria or initial hypotheses. These candidates then undergo evaluation, typically involving computational simulations – such as density functional theory or molecular dynamics – or experimental characterization to assess their properties against desired performance indicators. The results of this evaluation phase are then fed back into the system, informing the refinement of the candidate generation strategy; this may involve adjusting search parameters, modifying the underlying algorithms, or incorporating newly learned relationships between material features and properties, thereby iteratively improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the discovery process.

An LLM Orchestrator functions as the central control system within a closed-loop discovery framework, automating the iterative process of materials exploration. This component receives initial prompts or objectives, then utilizes large language models to generate candidate materials based on defined criteria. It then coordinates the evaluation of these candidates – potentially leveraging simulations, databases, or experimental feedback – and interprets the results to refine subsequent candidate generation. This orchestration involves managing the flow of information between different modules, prioritizing promising materials, and adapting the search strategy based on performance metrics, effectively acting as the ‘brain’ that drives the autonomous discovery cycle.

Effective materials discovery within a closed-loop framework relies on robust candidate generation and prioritization techniques. These methods must efficiently explore the chemical space, proposing materials with a high probability of possessing desired properties. Ranking algorithms are then critical for ordering these candidates, considering factors such as predicted performance, synthetic accessibility, and novelty. Approaches include machine learning models trained on materials data, coupled with optimization algorithms that balance exploration of diverse compositions with exploitation of promising regions. The efficacy of these methods directly impacts the speed and success rate of the iterative discovery process, determining the efficiency with which the framework can converge on optimal materials.

![Using an LLM orchestrator, discovery policies achieve enhanced exploration of quinary inter-metallic systems, as demonstrated by improvements in acceleration [latex]AF[/latex] and enhancement [latex]EF[/latex] factors compared to a random baseline, with shaded regions indicating standard error across multiple trials.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.20996v1/x1.png)

Intelligent Exploration: Accelerating the Search

Generative models are employed in materials discovery to propose novel chemical compositions and crystal structures. These models, often based on techniques like variational autoencoders or generative adversarial networks, are trained on existing materials data and learn the underlying principles governing chemical stability. This allows them to generate new candidate materials predicted to be stable, effectively navigating the vast chemical space. Stability prediction is typically incorporated as a constraint or reward signal during the generation process, often utilizing established criteria such as formation energy calculations based on density functional theory. The output of these models are then subjected to further validation through more computationally expensive methods or experimental synthesis.

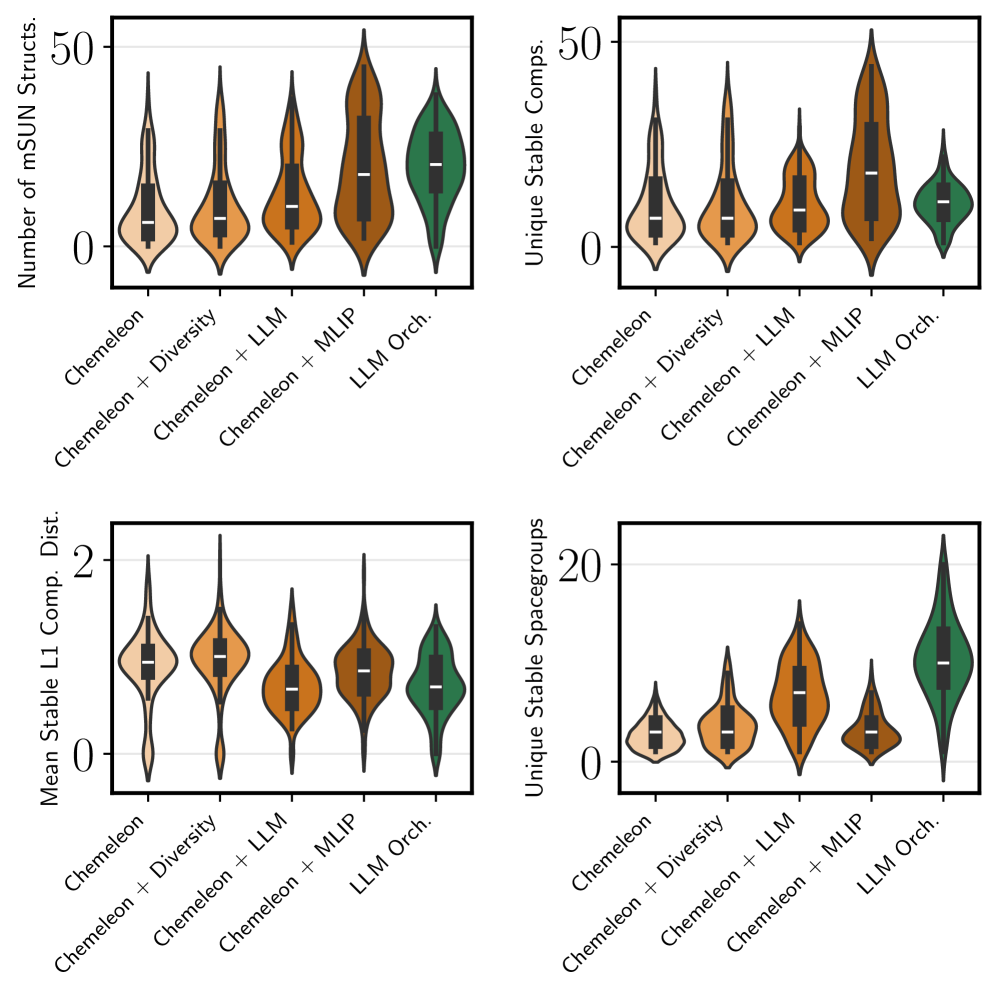

Diversity planning strategies in materials discovery are employed to maximize the coverage of ‘Chemical Space’ – the vast landscape of all theoretically possible chemical compositions and structures. These strategies aim to prevent algorithms from prematurely converging on a limited subset of materials with similar properties, a phenomenon that can hinder the identification of truly novel and optimal candidates. Techniques include penalizing the similarity of proposed materials to those already evaluated, or actively seeking out compositions and structures that are distant from the current dataset based on defined chemical descriptors. By enforcing a broader search, diversity planning increases the probability of discovering materials with unexpected and potentially superior characteristics, thereby enhancing the overall efficiency of the exploration process.

Surrogate models significantly reduce the computational cost associated with materials screening by approximating the results of more complex calculations. These models are frequently constructed using Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs), which are trained on datasets generated by ab initio methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT). Once trained, the MLIP can rapidly predict the energy and forces within a material, enabling the efficient calculation of properties like stability, elastic constants, and phonon spectra. This acceleration allows for the screening of a substantially larger portion of the chemical space compared to relying solely on computationally expensive first-principles calculations, ultimately expediting the discovery of novel materials.

The Materials Acceleration and Discovery Benchmark (MADE) is a standardized suite of computational tasks designed to assess the performance of materials discovery methods. It consists of ten distinct challenges, each focused on predicting a specific material property – including formation energy, band gap, and magnetic moment – for a curated set of crystal structures. Quantitative comparison between different algorithms is facilitated through a centralized scoring system that reports performance metrics such as mean absolute error [latex]MAE[/latex] and root mean squared error [latex]RMSE[/latex]. The benchmark utilizes a held-out test set, preventing overfitting and ensuring reliable evaluation of generalization capability. Publicly available datasets and evaluation protocols enable reproducible research and accelerate progress in the field of materials discovery.

![Planning algorithms consistently outperform baseline methods in identifying stable configurations, demonstrating robustness even with reduced tolerance, while surrogate model ranking exhibits diminished performance with stricter stability criteria [latex]±[/latex] standard error across multiple systems.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.20996v1/x5.png)

Beyond Prediction: The Implications for Future Discovery

The identification of stable inter-metallic compounds hinges on understanding the delicate balance between formation energy and thermodynamic stability. This framework capitalizes on this relationship by employing the concept of the ‘Convex Hull’, a graphical representation that defines the lowest energy state for a given composition. Compounds falling below the convex hull are predicted to be unstable and decompose, while those residing on or within it represent stable phases. By accurately calculating formation energies and comparing them to the convex hull, the system efficiently filters potential inter-metallic compounds, prioritizing those likely to exist and possess desirable properties. This method offers a robust and computationally efficient means of navigating the vast chemical space of possible materials, effectively predicting stable compounds and accelerating materials discovery.

A robust assessment of the framework’s performance relied on comparison with a ‘Random Search’ strategy, a common method for materials exploration. This approach, while simple, provided a crucial baseline for evaluating the efficacy of the closed-loop optimization process. Results indicated the framework consistently outperformed random searching, demonstrating its ability to intelligently navigate the vast materials space and efficiently identify promising compounds. The significant improvement over purely stochastic methods underscores the value of incorporating predictive modeling and active learning into materials discovery, highlighting the framework’s potential to accelerate the development of novel materials with desired properties.

Evaluations using the Materials Acceleration for Discovery and Exploration (MADE) benchmark reveal a substantial increase in the rate of novel material discovery facilitated by this framework. The system achieved an Acceleration Factor of 6.4, meaning it identified promising intermetallic compounds six and a half times faster than traditional methods. This performance is notably comparable to that of highly optimized pipelines, such as the Chemeleon and Machine Learning Interatomic Potential (MLIP) combination, which represent state-of-the-art approaches in materials science. The demonstrated efficiency suggests this framework provides a viable and competitive pathway for accelerating the identification of materials with desired properties, potentially revolutionizing materials discovery timelines.

The study demonstrates that an LLM-based orchestrator significantly accelerates materials discovery, achieving an Enhancement Factor of 6.0. This performance is noteworthy as it rivals the efficiency of established, highly-tuned pipelines such as Chemeleon combined with Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIP). This result suggests that the LLM isn’t merely automating existing search processes, but actively improving upon them through adaptive strategies. By intelligently navigating the materials design space, the LLM effectively prioritizes promising candidates, reducing computational cost and accelerating the identification of novel materials with desired properties. The framework’s success highlights the potential for LLMs to move beyond simple automation and function as intelligent research assistants capable of driving genuine innovation in materials science.

The pursuit of materials discovery, as outlined in this work, isn’t simply about finding solutions – it’s about systematically dismantling assumptions. The authors highlight the necessity of adaptive planning within closed-loop systems, acknowledging that initial models inevitably degrade with increasing complexity. This resonates deeply with the sentiment expressed by Donald Davies: “The best way to predict the future is to create it.” Indeed, MADE isn’t just a benchmark; it’s a framework for actively shaping the search space, constantly refining the predictive models through iterative experimentation. The environment demands a willingness to break down existing approaches, mirroring Davies’ belief in proactive construction over passive observation, and recognizing that true understanding comes from building – and rebuilding – systems from the ground up.

What’s Next?

The MADE benchmark, while a step towards automated materials discovery, ultimately highlights just how little of the code governing material properties has been deciphered. Current generative models, even within a closed-loop optimization framework, are merely sophisticated pattern-completion engines. Their success isn’t a testament to ‘understanding’ materials science, but to exploiting correlations within limited datasets. As search spaces expand – as they inevitably must – these correlations weaken, and the inherent unreliability of surrogate models becomes painfully obvious. The real challenge isn’t building better optimizers; it’s developing methods to actively debug those models – to identify where the approximations break down and direct exploration toward genuinely novel chemical space.

Future iterations of this work should move beyond simply measuring discovery ‘efficiency’. The focus needs to shift towards quantifying the quality of the discovered materials – their potential for unforeseen functionalities, their robustness to environmental factors, and, crucially, the degree to which their properties can be accurately predicted a priori. A system that rapidly generates plausible-sounding but ultimately useless materials is hardly an advancement.

Ultimately, this entire field operates under the assumption that materials science is a code that can be cracked. That reality is open source – we just haven’t read it yet. The next phase demands not just algorithmic refinement, but a fundamental re-evaluation of how knowledge is represented, how uncertainty is managed, and how experimentation itself can be treated as an iterative debugging process.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20996.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Gold Rate Forecast

- How to get the new MLBB hero Marcel for free in Mobile Legends

- Alan Ritchson’s ‘War Machine’ Netflix Thriller Breaks Military Action Norms

- Clash Royale Chaos Mode: Guide on How to Play and the complete list of Modifiers

- 10 New Books You Should Read in March

2026-01-31 09:21