Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis reveals that popular methods for understanding how large language models work are often fundamentally flawed and can paint a misleading picture of their internal reasoning.

![The study challenges the common assumption of positional consistency in word embeddings across BERT’s internal layers, suggesting that attention head activations, as visualized with tools like BertViz, demonstrate a dynamic shift in how words are represented during processing [latex] [8, 18] [/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.22928v1/Figures/Bertviz4.png)

Rigorous testing demonstrates that attention mechanisms and embedding space analysis frequently produce spurious correlations and fail to accurately reflect semantic understanding in transformer models.

Despite the increasing deployment of Large Language Models (LLMs), a fundamental understanding of how they achieve their impressive performance remains elusive. This work, titled ‘LLMs Explain’t: A Post-Mortem on Semantic Interpretability in Transformer Models’, critically examines the validity of prevalent interpretability techniques-attention mechanism analysis and embedding-based property inference-used to probe the inner workings of these models. Our findings demonstrate that these methods often fail under rigorous testing, producing misleading signals driven by methodological artifacts rather than genuine semantic understanding. This raises a critical question: can we reliably interpret LLMs, and what alternative approaches are needed to ensure trustworthy deployment in pervasive and distributed computing systems?

The Black Box Problem: Why We Can’t Trust What LLMs “Think”

Despite the impressive capabilities of Large Language Models in tasks ranging from text generation to code completion, a fundamental challenge persists: these systems operate as largely impenetrable “black boxes”. While an LLM might accurately translate languages or answer complex questions, the reasoning behind these outputs remains obscure, making it difficult to ascertain why a particular response was generated. This opacity isn’t merely an academic concern; it directly impacts trust and control. Without understanding the internal logic, validating the reliability of outputs – especially in high-stakes applications like medical diagnosis or legal advice – becomes problematic. The lack of interpretability also raises concerns about potential biases embedded within the model, as identifying and mitigating unfair or discriminatory outcomes requires insight into the decision-making process. Consequently, unlocking the internal workings of LLMs is crucial not only for advancing artificial intelligence but also for responsible deployment and widespread adoption.

The sheer scale of modern Large Language Models presents a fundamental challenge to interpretability; techniques that successfully dissected smaller neural networks simply don’t translate. Analyzing billions of parameters to pinpoint the precise reasoning behind a model’s output is akin to searching for a few meaningful signals within a vast ocean of noise. Existing methods often focus on individual neurons or layers, failing to capture the complex interplay that generates semantic understanding. Consequently, while a model might produce coherent text, determining why it arrived at a specific conclusion remains elusive. This disconnect between scale and semantic meaning necessitates the development of novel approaches-techniques capable of abstracting away from the parameter count and revealing the underlying logic driving these powerful, yet often inscrutable, systems.

The deployment of Large Language Models in high-stakes areas – such as healthcare, finance, and criminal justice – demands a clear understanding of their reasoning processes. Simply observing that an LLM reaches a certain conclusion is insufficient; knowing how it arrived at that conclusion is paramount for ensuring reliability and mitigating potential harms. A lack of interpretability introduces risks of biased outputs, undetected errors, and a general inability to guarantee responsible AI behavior. Consequently, research focuses on techniques that can illuminate the internal logic of these models, revealing which features or data points most strongly influenced a particular decision and providing confidence that conclusions are based on sound reasoning rather than spurious correlations or unintended biases. This pursuit of transparency isn’t merely academic; it’s a prerequisite for building trust and enabling the safe and ethical integration of LLMs into critical societal functions.

Mapping Meaning: Decoding LLM “Thoughts” Through Embeddings

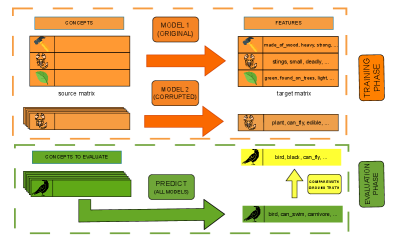

Embedding-Based Property Inference represents a significant advancement in Large Language Model (LLM) interpretability by establishing a direct correspondence between the LLM’s internal, numerical representations – token embeddings – and concepts readily understood by humans. This approach circumvents the ‘black box’ nature of LLMs by moving beyond simply observing outputs to analyzing the vector space where words and concepts are encoded. The core principle involves identifying how specific dimensions within these embedding vectors correlate with predefined human-understandable attributes or ‘properties’. Consequently, researchers can quantitatively assess the LLM’s implicit understanding of concepts, moving from speculation about internal reasoning to data-driven insights into its knowledge representation.

Token embeddings are fundamental to decoding Large Language Model (LLM) reasoning because they transform discrete input tokens – individual words or sub-word units – into continuous vector representations. These vectors, typically of high dimensionality, capture semantic and syntactic information about the token, allowing the LLM to perform mathematical operations on them. The process involves assigning each token in the LLM’s vocabulary a unique vector; similar tokens, based on co-occurrence patterns in the training data, will have vectors that are close to each other in the vector space. This allows the LLM to generalize from known tokens to unseen ones, and enables property inference techniques to map these vector representations onto human-understandable features, thereby revealing how the LLM internally represents concepts.

Mapping token embeddings to Feature Norms allows for quantifiable analysis of an LLM’s conceptual understanding. Feature Norms are established datasets detailing the degree to which words activate specific psychological properties – for example, ratings of ‘animacy’, ‘edibility’, or ‘social impact’. By calculating the cosine similarity between a token embedding and the vector representation of a given Feature Norm, researchers can determine the strength of association between that token and the corresponding property. Higher similarity scores indicate a stronger correlation, suggesting the LLM internally represents the token as possessing that attribute; this provides a method for identifying the semantic features the model has encoded and how it differentiates between concepts based on these features.

From Linear Regression to Neural Networks: Tools for Peeking Inside the Box

Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) offers a computationally efficient method for establishing a linear relationship between high-dimensional embedding spaces and a set of interpretable features. PLSR achieves this efficiency by reducing dimensionality through the creation of latent variables, which are linear combinations of the original predictor variables (embeddings). These latent variables maximize the covariance between the embeddings and the target features, allowing for a simplified regression model to be trained. This approach is particularly useful as an initial baseline due to its relatively low computational cost and ease of implementation, providing a quick assessment of the potential for feature approximation before employing more complex, resource-intensive models.

Feedforward Neural Networks, in contrast to linear models, introduce non-linear activation functions between layers, enabling the representation of complex relationships between input embeddings and interpretable features. This increased model capacity is achieved through the composition of multiple layers, each applying a weighted sum of its inputs followed by a non-linear transformation – typically ReLU, sigmoid, or tanh. The trainable weights within these layers allow the network to learn hierarchical representations, effectively modeling interactions and dependencies that linear methods cannot capture. Consequently, Feedforward Neural Networks can potentially achieve higher accuracy in decoding tasks where the relationship between embeddings and features is not strictly linear, though this comes at the cost of increased computational complexity and a larger number of trainable parameters.

Evaluation of decoding methods revealed surprisingly robust performance even when feature assignments were randomized. Specifically, models utilizing techniques like Feedforward Neural Networks maintained competitive F1@10 scores despite being trained and tested with deliberately shuffled feature vectors. This outcome suggests these models are heavily reliant on structural properties within the embedding space – such as vector magnitudes or relative positions – rather than genuine semantic relationships between features and corresponding outputs. The continued high performance with randomized features indicates a limited capacity to leverage semantic information and a strong dependence on superficial patterns present in the data.

The Illusion of Understanding: Why Token Identity Is a Myth

The foundational premise of many natural language processing models – that a token’s identity is preserved within its evolving hidden representation throughout a transformer network – is facing increasing scrutiny. Historically, it was assumed that despite layers of processing, a model could still ‘trace’ a given input token through the network’s hidden states. However, the very architecture of transformers, with mechanisms like multi-head mixing and residual connections, actively works against this ‘token continuity assumption’. These processes diffuse and redistribute information, blending token-specific features across the entire representation. Consequently, the connection between an input token and its corresponding hidden representation weakens with each successive layer, raising questions about the extent to which transformers truly ‘understand’ the semantic content of individual tokens, and instead rely on more abstract, geometric relationships within the data.

The architecture of modern transformers, while powerful, inherently challenges the notion of persistent token identity. Processes such as Multi-Head Mixing actively diffuse information across the entire sequence, blending token representations and diminishing the unique contribution of any single input element. Simultaneously, Residual Connections, designed to facilitate gradient flow during training, also contribute to this dissolution by allowing information from earlier layers – and thus, initial token embeddings – to be repeatedly transformed and mixed with subsequent layer outputs. This creates a complex interplay where token-specific information isn’t necessarily lost, but rather becomes increasingly distributed and entangled within the broader contextual representation, making it difficult to isolate or attribute meaning directly back to the original input token.

While attention mechanisms in transformer models are often interpreted as highlighting the relational importance between tokens, recent investigations suggest this connection may be misleading. Analyses relying solely on attention weights to infer semantic relationships require careful consideration, as predictive performance can be surprisingly robust even when the underlying semantic content is severely compromised. Testing revealed that Spearman’s ρ – a measure of statistical dependence – remains consistently high even with deliberately corrupted input features, indicating that the model’s ability to predict outcomes isn’t necessarily tied to accurate semantic decoding. This suggests that models may be leveraging other cues, such as geometric relationships within the embedding space, rather than genuine understanding of the input’s meaning, challenging the direct interpretation of attention weights as indicators of semantic relevance.

Recent analyses of transformer models reveal a surprising reliance on geometric relationships within the embedding space, rather than genuine semantic understanding. Investigations utilizing Neighborhood Accuracy@10 – a metric assessing whether the closest embeddings represent similar inputs – demonstrate consistently competitive scores even when the input features are thoroughly shuffled. This suggests the model isn’t actually decoding semantic content to find neighbors, but is instead identifying points that are geometrically close in the high-dimensional space, effectively leveraging a form of clustering. The model excels at recognizing patterns of proximity, indicating that much of its predictive power stems from these spatial arrangements rather than a grasp of the underlying meaning of the tokens themselves. This highlights a fundamental limitation in interpreting transformer representations as direct encodings of semantic information.

Beyond Interpretation: The Future of LLMs and Pervasive Intelligence

Large language models (LLMs) are rapidly transitioning from centralized cloud services to deployment within Edge AI and pervasive computing environments, necessitating innovative strategies for efficiency and resilience. This shift demands more than simply shrinking model size; it requires careful consideration of computational constraints, energy consumption, and the need for continuous operation even with intermittent connectivity. Researchers are actively exploring techniques like model quantization, pruning, and knowledge distillation to reduce the computational footprint of LLMs without significant performance degradation. Furthermore, robust deployment strategies incorporate techniques for on-device learning, federated learning, and adaptive resource allocation, enabling these models to operate reliably in dynamic and unpredictable real-world scenarios – from smart sensors and autonomous vehicles to personalized healthcare devices and augmented reality systems.

Large language models demonstrate a remarkable capacity for abstraction, extending learned knowledge to novel situations-a cornerstone of general intelligence. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches reliant on explicit programming for each specific task, LLMs can generalize from patterns observed in vast datasets, effectively applying previously acquired understanding to new, unseen instances. This isn’t simply memorization; the models identify underlying principles and relationships, allowing them to perform tasks – such as generating creative content, translating languages, or answering complex questions – with minimal task-specific training. While ensuring these models remain interpretable is vital for trust and safety, this inherent ability to abstract knowledge represents a core strength, promising transformative applications across diverse fields and paving the way for more robust and adaptable pervasive intelligence systems.

The future scalability of large language models hinges on concurrent advancements in understanding how they arrive at conclusions and how to build more efficient systems. Current research isn’t solely focused on making LLMs explainable, but also on fundamentally improving their architecture to enhance reasoning and reduce computational demands. This dual approach-interpretability paired with architectural innovation-promises to extend LLM applications far beyond current limitations. Innovations such as sparse activation, quantization, and novel attention mechanisms aim to deploy these powerful models on resource-constrained devices, while refined interpretability techniques will build trust and allow for error correction in critical applications like healthcare and autonomous systems. Ultimately, unlocking the full potential of LLMs requires a synergistic effort, fostering both transparency and performance to enable truly pervasive intelligence.

The pursuit of semantic interpretability in Large Language Models feels remarkably like polishing brass on the Titanic. This paper meticulously details how techniques – attention mechanisms, embedding analysis – routinely fail under scrutiny, revealing more about methodological quirks than actual model understanding. As Tim Berners-Lee observed, “The Web is more a social creation than a technical one.” Similarly, these interpretability methods are less about uncovering inherent model logic and more about the biases we introduce through data and evaluation. It’s a stark reminder that production will always find a way to break elegant theories, and the illusion of understanding is often more comforting than the messy reality of what’s actually happening within those layers.

The Road Ahead (Or, Why This Feels Familiar)

The demonstrated fragility of current interpretability methods is not, strictly speaking, surprising. The field consistently overestimates its ability to reverse-engineer complexity. Attention mechanisms, once hailed as providing clear insight into model reasoning, appear susceptible to spurious correlations and dataset-specific biases. Embedding space analyses, similarly, offer at best a limited view into the truly abstract representations learned by these models. The persistent belief in ‘feature inference’ – identifying single concepts within neuron activations – feels reminiscent of earlier attempts at knowledge representation, which ultimately crumbled under the weight of real-world ambiguity.

Future work will likely focus on more rigorous testing methodologies, moving beyond carefully curated examples to adversarial datasets designed to expose the limitations of these techniques. A shift towards causal inference, rather than mere correlation, is inevitable, though the practical difficulties remain substantial. The pursuit of ‘explainable AI’ may also benefit from a healthy dose of skepticism; perhaps understanding how a model fails is more valuable than attempting to justify its successes.

One suspects that any new interpretability framework, however elegant in theory, will eventually succumb to the same fate: becoming another layer of abstraction, obscuring the underlying chaos. If all tests continue to pass, it will likely be because they are measuring increasingly narrow and irrelevant criteria.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.22928.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- eFootball 2026 Show Time Worldwide Selection Contract: Best player to choose and Tier List

- James Van Der Beek grappled with six-figure tax debt years before buying $4.8M Texas ranch prior to his death

2026-02-03 06:25