Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new algorithm allows multi-robot systems to maintain complex formations and coordinated movements by focusing control on the swarm’s center of gravity.

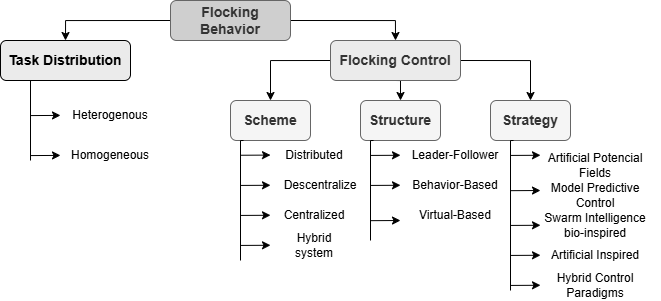

This review details FlockingBehavior, a decentralized control approach enabling dynamic, geometrically complex swarm structures and robust trajectory following.

Maintaining stable formations and coordinated movement remains a significant challenge for multi-robot systems operating in dynamic environments. This is addressed in ‘Flocking behavior for dynamic and complex swarm structures’, which introduces an algorithm-FlockingBehavior-that enables complex geometric formations and coordinated trajectories by assigning a single, shared trajectory to the swarm’s centroid. Through a virtual-based approach, the work provides a theoretical framework for dynamically controlling both the number of agents and the resulting structure’s configuration. Could this simplified centroid-based control paradigm unlock more robust and scalable swarm intelligence for real-world applications?

Decoding the Swarm: Collective Motion as a Systemic Advantage

Multi-Robot Systems (MRS) are increasingly recognized for their potential to outperform single robots in tasks demanding speed, coverage, and adaptability. The advantage isn’t simply additive; a coordinated group can navigate complex environments and manipulate objects with a dexterity and efficiency unattainable by a lone machine. However, realizing this potential hinges on overcoming significant coordination challenges. Each robot’s actions must be intelligently interwoven with those of its peers, demanding robust algorithms capable of handling uncertainty, communication delays, and potential failures. Unlike pre-programmed routines, effective MRS require dynamic strategies that allow robots to react to changing conditions and maintain cohesive behavior-a complex undertaking necessitating advanced control architectures and sophisticated inter-agent communication protocols.

The elegance of a murmuration of starlings, or a school of fish, has increasingly informed the field of multi-robot systems. This bio-inspired approach, known as flocking behavior, offers a compelling solution to the challenges of coordinating large numbers of autonomous agents. Rather than relying on centralized control – a system prone to failure and limited in scalability – flocking algorithms empower each robot to react solely to its immediate neighbors, following a few simple rules: alignment, cohesion, and separation. This decentralized methodology yields remarkably robust and adaptable collective movement, allowing the group to navigate complex environments, avoid obstacles, and even reform after disruptions without a single point of failure. The inherent scalability of these algorithms means the system’s performance doesn’t degrade significantly as the number of agents increases, making it a promising technique for applications ranging from environmental monitoring and search-and-rescue operations to coordinated manufacturing and space exploration.

Successfully deploying multi-robot systems hinges on a deep comprehension of the principles that govern collective movement and control, moving beyond simple individual programming. Researchers are discovering that mirroring natural flocking behaviors – seen in bird formations or fish schools – requires modeling surprisingly few, localized rules. Each agent responds only to its immediate neighbors, adjusting its velocity and position based on these interactions to maintain cohesion, separation, and alignment. This decentralized approach offers remarkable robustness; the system doesn’t rely on a central controller, meaning the failure of one robot doesn’t necessarily compromise the entire group. Furthermore, this bio-inspired methodology scales effectively, allowing for the coordination of hundreds, or even thousands, of agents without a proportional increase in computational complexity – a crucial characteristic for real-world applications ranging from environmental monitoring to search and rescue operations.

![The swarm operates within an inertial world frame [latex]W[/latex], coordinating agent positions relative to a virtual centroid [latex]VC[/latex] to enable collective behavior.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21772v1/frames_flocking.png)

The Boids Algorithm: Simulating Emergent Order

The Boids algorithm simulates flocking behaviors by applying three fundamental principles to each agent within the simulation. Cohesion directs each agent to steer towards the average position of nearby agents, promoting group proximity. Separation ensures that agents maintain a minimum distance from their neighbors, preventing collisions and overcrowding. Finally, alignment causes agents to adjust their velocity to match the average velocity of nearby agents, creating coordinated movement. These rules are applied independently and locally to each agent at each time step, resulting in a global, emergent flocking behavior without any central control or explicit communication between agents.

The Boids algorithm achieves coordinated group behavior not through centralized control, but through the application of three local rules to each individual agent, often referred to as “boids”. Each boid assesses the positions and velocities of its nearby neighbors and adjusts its own movement accordingly. Cohesion steers the boid towards the average position of its neighbors, while separation ensures it maintains a minimum distance to avoid collisions. Alignment modifies the boid’s velocity to match that of its neighbors. These rules, calculated and applied independently by each agent, produce a global, emergent flocking behavior without any explicit coordination or leader-follower relationships; the resulting patterns are a consequence of numerous local interactions.

The principles of cohesion, separation, and alignment, as defined in the Boids algorithm, provide a decentralized control framework applicable to multi-robot systems. By implementing these localized rules – steering towards the average heading of nearby robots (alignment), maintaining a minimum distance from others (separation), and moving towards the average position of the group (cohesion) – complex coordinated behaviors emerge without central control or pre-defined paths. This approach offers robustness against individual robot failures, as the collective behavior is not dependent on any single unit. Furthermore, adaptability is achieved through the localized nature of the rules, allowing the swarm to respond dynamically to changes in the environment or the introduction of new robots without requiring global replanning or communication.

Beyond Simple Flocking: Architectures for Complex Swarm Behavior

Beyond basic flocking behaviors, advanced coordination in multi-robot systems (MRS) utilizes hierarchical control structures. Leader-follower approaches designate specific robots as leaders, with the remaining robots maintaining predefined positional relationships. Pinning-based control allows for stabilization of the entire system by controlling only a subset of robots – the “pinned” nodes – while the others react to their movements. Virtual-based architectures, conversely, introduce virtual robots or leaders that do not physically exist but dictate the desired formation or behavior, enabling more complex and adaptable swarm dynamics without requiring direct control of every agent. These methods offer increased flexibility and scalability compared to centralized control, facilitating robust performance in dynamic environments and enabling complex task allocation.

Advanced control structures facilitate the implementation of Geometric Rigid Formations (GRFs) in multi-robot systems (MRS), moving beyond simple flocking behaviors. GRFs define specific spatial relationships between robots that are maintained throughout operation, enabling coordinated maneuvers and task execution. These formations aren’t limited to maintaining distance; they can enforce specific angles, orientations, and relative positions, crucial for applications like precision assembly or environmental mapping. Simultaneously, these control structures allow for differentiated task assignment; rather than all robots performing the same action, each robot within a GRF can be assigned a unique role based on its position or capabilities, increasing the overall efficiency and complexity of the swarm’s operations. The combination of GRFs and task specialization enables the MRS to address more intricate problems and adapt to varying environmental demands.

Advanced control structures facilitate robust multi-robot system (MRS) operation by enabling dynamic adaptation to changing conditions. These techniques move beyond pre-programmed trajectories, allowing robots to modify their behavior based on real-time sensor data and evolving objectives. This adaptability is achieved through decentralized decision-making and communication protocols, permitting the MRS to reconfigure formations, redistribute tasks, and circumvent obstacles without requiring central intervention. Consequently, MRS employing these methods demonstrate increased resilience in unpredictable environments and improved performance when confronted with unforeseen circumstances or shifting priorities, supporting applications requiring continuous operation and objective fulfillment despite external disturbances.

![Before collective movement begins, UAVs position themselves relative to a virtual centroid [latex]t_{s}[/latex] following an initial configuration at [latex]t_{0}[/latex], with the red dot indicating the centroid’s position and the green arrow its forward orientation.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21772v1/ready.png)

Orchestrating the Swarm: Trajectory Following and Task Distribution

Successful multi-robot mission execution is fundamentally dependent on two core capabilities: trajectory following and task distribution. Trajectory following ensures each robot accurately navigates a predetermined path, maintaining spatial relationships and operational sequencing. Simultaneously, efficient task distribution involves allocating specific objectives to individual robots, optimizing for factors such as robot capabilities, proximity to the task, and overall mission completion time. The interplay between these two capabilities is critical; robots must not only adhere to their assigned paths but also effectively execute the tasks associated with those paths, necessitating a coordinated control architecture to manage both navigation and action.

The FlockingBehavior Algorithm, as implemented in this research, establishes a methodology for generating complex multi-robot trajectories through decentralized control. This approach centers on the concept of a Virtual Centroid, a calculated point in space that serves as a collective target for all agents. Each robot adjusts its velocity and position based on its proximity to this centroid and the positions of its immediate neighbors, fostering cohesive movement. The algorithm utilizes three primary behavioral rules – separation, alignment, and cohesion – to govern individual robot actions, enabling the swarm to navigate and maintain formation without relying on a central planner or global map. This decentralized framework promotes scalability and resilience, allowing the system to adapt to dynamic environments and potential robot failures.

Simulation results, utilizing up to 12 drone agents, demonstrate the system’s ability to recover from simulated drone failures within 1.5 seconds. This reconfiguration time was achieved while maintaining a relative speed, or alignment, of less than 0.15 m/s between the remaining agents. These metrics indicate the system’s capacity for rapid adaptation and continued mission execution following a disruption, highlighting its robustness in dynamic environments. The performance was consistently observed across multiple simulation runs with varying failure scenarios.

Artificial Potential Fields (APF) augment multi-robot system robustness by introducing repulsive forces from obstacles and attractive forces towards goals. This allows robots to dynamically adjust their trajectories to avoid collisions, even in environments with static or moving impediments. The potential field is mathematically defined such that the resultant force on a robot is a vector sum of these attractive and repulsive influences, guiding it along a safe path. Implementation involves defining potential field functions that quantify the distance to obstacles and goals, then calculating the gradient of the combined potential to determine the force vector. This approach offers a computationally efficient method for real-time obstacle avoidance and collision prevention, supplementing trajectory following algorithms and contributing to overall mission reliability.

Beyond Homogeneity: Expanding the Horizon of Multi-Robot Systems

The elegance of flocking behavior, traditionally observed in groups of identical agents, proves surprisingly adaptable to heterogeneous systems – robotic collectives comprised of diverse units with specialized functions. Researchers are demonstrating that the core principles of decentralized control, such as local interaction rules and collision avoidance, can be extended to orchestrate teams where each robot fulfills a unique role, be it scouting, construction, or resource transport. This isn’t merely about adding variety; it’s about leveraging complementary capabilities. A team might consist of agile drones for aerial reconnaissance, robust ground vehicles for heavy lifting, and nimble robots for intricate manipulation, all working in concert through a shared understanding of collective goals and spatial awareness. By assigning roles and allowing robots to dynamically adjust their behavior based on their specialization and the surrounding environment, these systems achieve a level of robustness and efficiency unattainable with uniform agents, opening doors to complex tasks in fields like search and rescue, environmental monitoring, and automated construction.

The integration of decentralized control and higher-level planning represents a significant advancement in multi-robot system design, enabling solutions that are both resilient and adaptable. Decentralized control allows each robot to react quickly to local stimuli and maintain operational stability even when communication is limited or disrupted. However, pairing this reactive capability with a broader, overarching plan-orchestrated by a higher-level system-facilitates coordinated behavior and task allocation. This synergy unlocks the potential for robust performance in complex scenarios, such as large-scale environmental monitoring, collaborative search and rescue operations, and dynamic warehouse logistics. Scalability is achieved because the computational burden isn’t centralized; instead, it’s distributed across the robots, allowing the system to expand gracefully as the number of agents increases without sacrificing responsiveness or efficiency. Ultimately, this approach promises to deliver multi-robot solutions that are not only more effective but also more practical for real-world deployment.

Ongoing investigations are increasingly centered on cultivating multi-robot systems exhibiting heightened adaptability and intelligence, specifically designed for operation within genuinely complex and unpredictable environments. This pursuit involves not merely improving individual robot capabilities, but fostering sophisticated inter-robot communication and collaborative decision-making protocols. Researchers are exploring techniques such as reinforcement learning and evolutionary algorithms to enable these systems to learn from experience and dynamically adjust strategies in response to unforeseen circumstances. A key challenge lies in developing robust perception systems capable of accurately interpreting ambiguous or incomplete sensor data, coupled with efficient planning algorithms that can generate feasible solutions under tight time constraints. Ultimately, the goal is to create robotic teams that can autonomously explore, map, and manipulate objects in dynamic settings, mirroring the flexibility and resilience observed in natural swarms and social animal groups.

The pursuit of coordinated movement in multi-robot systems, as detailed in this work, mirrors a fundamental principle of distributed systems: emergent behavior from simple rules. This echoes Tim Bern-Lee’s sentiment: “The Web is more a social creation than a technical one.” Just as the Web’s complexity arises from interconnected, yet basic, protocols, so too does the sophisticated flocking behavior emerge from the application of Reynolds’ rules to each robot. The algorithm’s focus on assigning a single trajectory to the centroid isn’t about centralized control, but rather about establishing a shared understanding – a common ‘address’ – allowing individual agents to navigate a complex space with collective coherence. It’s a system confessing its design sins – revealing how constrained rules can give rise to unexpectedly graceful and adaptable formations.

Beyond the Flock

The elegance of assigning a single trajectory to a swarm’s centroid is, predictably, not without its fault lines. This work represents an exploit of comprehension – a successful reduction of complex, distributed motion to a surprisingly simple control law. Yet, the system’s inherent reliance on a globally defined, yet locally executed, trajectory invites scrutiny. What happens when that trajectory becomes…uncooperative? Or, more provocatively, when the very notion of a ‘centroid’ loses meaning in a highly dynamic environment? The current framework addresses formation following; a true test lies in formation generation – allowing the swarm to autonomously define and maintain structures based on environmental stimuli, not pre-programmed directives.

Further investigation must address the inevitable breakdown of cohesion as swarm density increases. Reynolds’ rules, while foundational, are fundamentally reactive. They address immediate neighbor interactions, but offer limited foresight regarding cascading collisions or emergent, undesirable formations. The next iteration demands proactive strategies – perhaps a form of distributed ‘intention’ where robots anticipate future states and adjust accordingly, essentially predicting, and then circumventing, their own failures.

Ultimately, the true challenge isn’t merely controlling a flock, but understanding the conditions under which the flock controls itself. The algorithm presented here isn’t an end, but a carefully constructed perturbation-a lever to pry open the mechanisms of collective behavior. The real insights will emerge not from perfecting the flock, but from deliberately breaking it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21772.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- Magic Chess: Go Go Season 5 introduces new GOGO MOBA and Go Go Plaza modes, a cooking mini-game, synergies, and more

- Bikini-clad Jessica Alba, 44, packs on the PDA with toyboy Danny Ramirez, 33, after finalizing divorce

- Gold Rate Forecast

- James Van Der Beek grappled with six-figure tax debt years before buying $4.8M Texas ranch prior to his death

2026-02-01 17:15