Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have successfully trained a small-scale neuromorphic chip to control a robot playing air hockey, demonstrating the potential of event-driven processing for real-time robotic applications.

![The system orchestrates a feedback loop where sensory data-specifically puck and end-effector positions [latex] (x_p, y_p, v_x, v_y, x_{ee}, y_{ee}) [/latex]-is translated into spike trains, processed by silicon neurons within a DYNAP-SE reservoir, and ultimately decoded into discrete motion primitives [latex] (q_1, q_2, q_3) [/latex] driving robot joint commands, all within a 1.038m x 1.948m environment designed to guide a puck towards designated arrival points through Action 0 or 1.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.21548v1/img/figure1.png)

This work showcases spiking reinforcement learning with a 1020-neuron analog-digital chip (DYNAP-SE) achieving control of a robotic system in a complex, dynamic task.

Controlling fast-paced robotic systems presents a significant challenge for traditional computing architectures, demanding both speed and energy efficiency. This is addressed in ‘Training slow silicon neurons to control extremely fast robots with spiking reinforcement learning’, which demonstrates successful robotic control using a small-scale neuromorphic system trained with spiking reinforcement learning to play air hockey. By leveraging a mixed-signal analog/digital chip with [latex]1020[/latex] neurons and an event-driven learning rule, the researchers achieved real-time learning with remarkably few training trials. Could this co-design of brain-inspired hardware and algorithms unlock new possibilities for low-power, autonomous robotics in complex, dynamic environments?

The Illusion of Control: Modeling the Unpredictable

Conventional robotic control systems often depend on meticulously crafted models of the robot and its environment. While effective in static, predictable settings, this approach demands substantial computational power for both planning and execution. The need for precise modeling becomes a significant limitation when confronted with dynamic environments-those subject to unpredictable changes or disturbances-as even minor discrepancies between the model and reality can lead to control failures. This reliance on detailed, pre-calculated solutions hinders a robot’s ability to react swiftly and appropriately to unforeseen circumstances, impacting its adaptability and overall performance in real-world applications. Consequently, researchers are increasingly exploring alternative control strategies that prioritize efficiency and robustness over absolute precision, seeking to mimic the intuitive and flexible control observed in biological systems.

Current robotic control systems often struggle with the unpredictable nature of real-world environments, largely because they depend on meticulously detailed models and substantial computational power. A move toward truly adaptable robots necessitates abandoning these traditional approaches in favor of strategies inspired by biological systems. The human brain, for example, achieves remarkable dexterity and responsiveness with astonishing efficiency; replicating this involves prioritizing streamlined processing and leveraging feedback loops that allow for continuous correction and learning. This paradigm shift focuses on creating controllers that aren’t simply programmed with pre-defined movements, but instead learn to react to stimuli in real-time, anticipating changes and adjusting accordingly – a hallmark of natural, fluid motion and a critical step toward robots that can operate effectively alongside humans in dynamic settings.

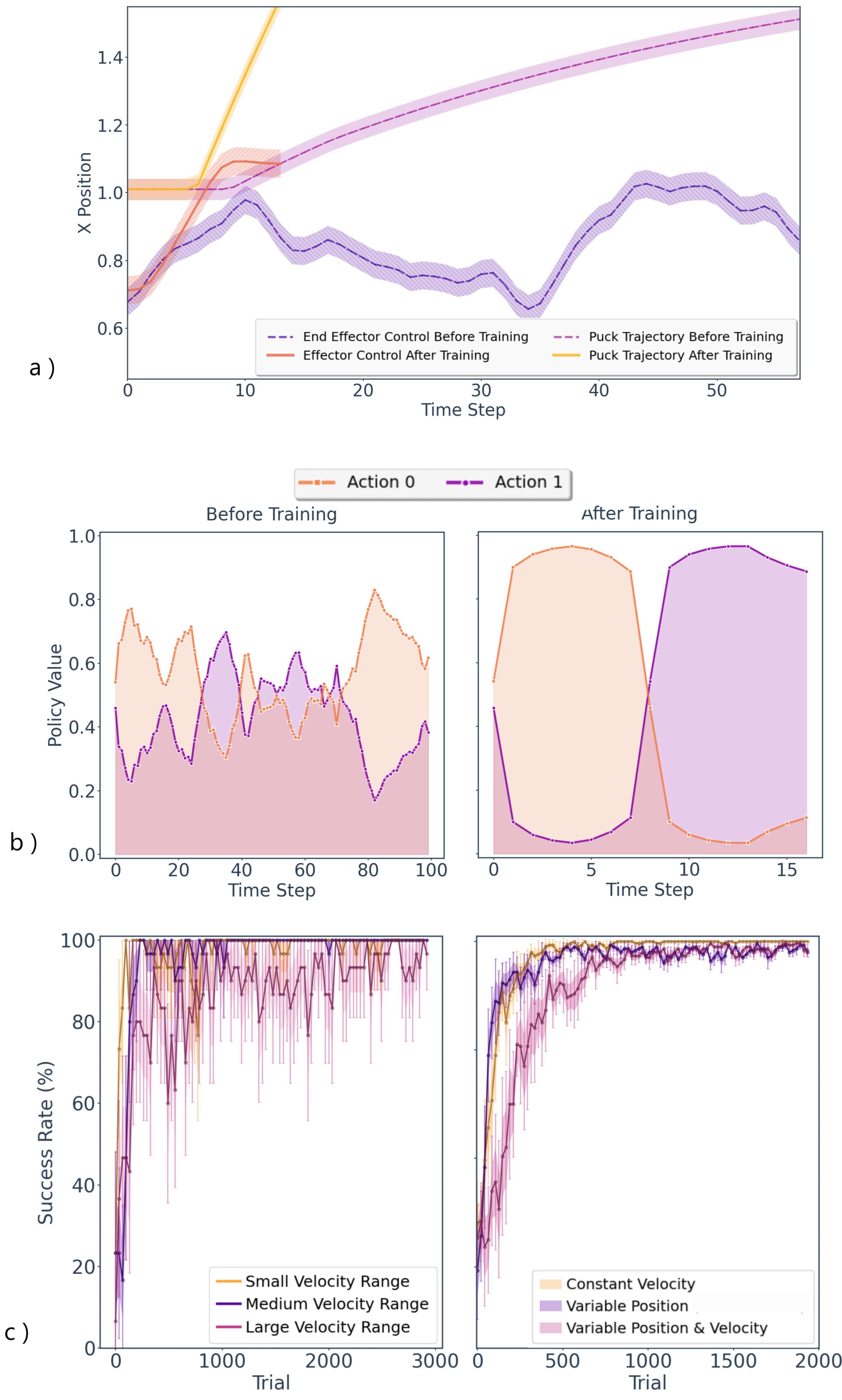

The pursuit of truly adaptable robotic systems is often assessed using complex environments, and the simulated game of air hockey has emerged as a particularly rigorous testbed. This isn’t simply a matter of hitting a fast-moving object; success demands a delicate balance of speed and precision, requiring the robotic agent to accurately predict the puck’s trajectory while reacting with sufficient velocity to intercept it. Researchers consider a consistently high performance – achieving a 96-98% success rate over an extended trial of 2000 episodes – as the benchmark for meaningful progress. Crucially, these episodes involve completely randomized starting conditions for the puck, varying both its initial position and velocity, forcing the control system to generalize beyond memorized patterns and demonstrate genuine, reactive skill. This demanding scenario pushes the boundaries of current robotic control techniques, highlighting the need for algorithms that can perform under pressure and adapt to unpredictable circumstances.

Bio-Inspired Efficiency: The Spiking Neural Network

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) achieve energy efficiency by deviating from the rate-based coding used in traditional Artificial Neural Networks. Biological neurons communicate via discrete, all-or-none action potentials, or “spikes,” and SNNs emulate this event-driven communication. Instead of transmitting continuous values, SNNs transmit information only when a neuron spikes, significantly reducing computational load and power consumption. This contrasts with traditional networks where every neuron continuously propagates a value, even if that value is zero. The asynchronous nature of spike transmission further minimizes energy expenditure as neurons only activate and communicate when necessary, leading to potentially orders-of-magnitude improvements in energy efficiency, particularly in hardware implementations.

Reservoir Computing (RC) leverages the dynamic properties of recurrent Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) to efficiently process time-varying inputs. Unlike traditional recurrent networks requiring training of all weights, RC maintains a fixed, randomly connected recurrent layer – the “reservoir” – and only trains a simple readout layer to map reservoir states to desired outputs. This significantly reduces computational cost and training time. The reservoir’s high-dimensional state space allows it to capture temporal dependencies in input data, making RC particularly effective for tasks involving sequential data such as speech recognition, gesture recognition, and, crucially, robotic control where processing sensor data over time is essential for stable and responsive behavior. The fixed reservoir weights simplify implementation and enable real-time performance on embedded systems.

Adaptive Precision Encoding (APE) facilitates the conversion of continuous analog signals from sensors into temporal spike patterns suitable for processing by Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). APE operates by dynamically adjusting the precision, or number of spikes, used to represent a given input value; larger deviations from a reference value trigger a higher spike count, while smaller deviations result in fewer spikes. This variable-precision representation allows SNNs to efficiently encode a wide dynamic range of sensor data while minimizing overall spike transmission, crucial for energy-constrained applications. The encoding process typically involves comparing the input signal to a threshold or baseline, then generating a burst of spikes with a frequency proportional to the difference, effectively translating analog intensity into temporal spike density.

Implementing Reactive Control: The SNN in Action

The event-based propagation (e-prop) learning rule facilitates efficient training of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) for robotic control by directly updating synaptic weights based on the timing of pre- and post-synaptic spikes. Unlike traditional gradient-based methods requiring backpropagation through time – which is biologically implausible and computationally expensive for SNNs – e-prop operates locally at each synapse. Weight updates are proportional to the correlation between incoming pre-synaptic events and outgoing post-synaptic events, effectively reinforcing pathways that contribute to desired behaviors. This local learning rule allows for scalable training and real-time adaptation in complex robotic control tasks, circumventing the limitations of conventional deep learning approaches when applied to event-based neural networks.

The Spiking Neural Network (SNN) architecture utilizes the Adaptive Exponential Integrate-and-Fire (AdEx-LIF) neuron model to balance biological plausibility with computational efficiency. AdEx-LIF neurons incorporate an adaptive threshold mechanism, allowing the firing threshold to change based on recent spiking activity; this captures the dynamic behavior observed in biological neurons, specifically the reduction in firing rate following periods of high activity. The model’s equations include a membrane potential governed by integration of synaptic currents and an exponential leak, alongside a threshold-dependent reset mechanism. This formulation provides a computationally tractable alternative to more complex biophysical models while retaining essential dynamic properties such as spike-frequency adaptation and realistic refractory periods, enabling efficient simulation and training within the robotic control framework.

The Spiking Neural Network (SNN) operates within a closed-loop control system facilitated by integration with the MuJoCo physics engine, specifically simulating the Air Hockey environment. This setup allows for reinforcement learning algorithms to be applied directly to the SNN’s control outputs, enabling it to learn optimal policies for manipulating the simulated paddle. The control loop operates at a frequency of 50 Hz, meaning the SNN receives state information from the environment and generates control signals 50 times per second, providing sufficient temporal resolution for effective control within the Air Hockey simulation.

The Illusion of Smoothness: Event-Driven Control and Prediction

The system demonstrates precise interception of a moving puck through a unique approach to continuous control, facilitated by Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs). Unlike traditional control systems, this architecture capitalizes on the inherent parallelism of SNNs – allowing numerous computations to occur simultaneously – and their low-latency processing, meaning actions are initiated with minimal delay. This enables the robot to react quickly to the puck’s trajectory. Crucially, the system doesn’t require complex calculations for every incremental movement; instead, it utilizes discrete actions – distinct “shots” – to effectively execute ballistic trajectories, approximating smooth, continuous control with a series of carefully timed impulses. This method allows for remarkably efficient and responsive maneuvering, achieving accurate intercepts despite the complexities of predicting a moving target.

Recent advancements in robotic control have been demonstrated through an implementation on the DYNAP-SE neuromorphic chip, utilizing a surprisingly compact network of only 1020 neurons. This system effectively showcases the potential for real-time, low-power operation without sacrificing performance; tests reveal comparable control accuracy to systems employing significantly larger neural networks – those with upwards of 10,000 neurons. The efficiency stems from the chip’s inherent ability to process information using asynchronous, event-driven spikes, mirroring biological neural processing and drastically reducing energy consumption. This achievement suggests a viable pathway towards deploying sophisticated robotic systems in resource-constrained environments, opening opportunities for applications ranging from autonomous drones to personalized assistive devices.

A key component of this control system is the integration of an event-based vision system with the spiking neural network (SNN) architecture, resulting in remarkably efficient visual information processing. Unlike traditional cameras that capture images at fixed intervals, event-based cameras only transmit data when a pixel detects a change in brightness, drastically reducing the volume of information that needs to be processed. This sparse, asynchronous data stream is ideally suited for SNNs, which naturally operate on spikes, minimizing computational demands and power consumption. By directly processing these visual ‘events’, the system avoids the need for computationally intensive frame-by-frame analysis, allowing for faster reaction times and improved performance in dynamic environments while simultaneously lowering the overall energy footprint of the robotic control system.

Towards Perpetual Adaptation: The Always-On Robot

The robotic framework distinguishes itself through its capacity for continuous refinement, enabling what is termed ‘Always-On Learning’. Unlike traditional robotic systems requiring periodic retraining, this approach allows the robot to perpetually adjust its control strategy based on real-time interactions with its surroundings. This is achieved by integrating incoming sensory data directly into the control loop, fostering a dynamic and self-improving process. As the robot operates, it subtly modifies its internal parameters, optimizing performance and enhancing its ability to navigate and respond to changing conditions without explicit external intervention. The result is a system exhibiting heightened resilience and adaptability, capable of maintaining consistent performance even in unpredictable or novel environments – a crucial step towards truly autonomous robotic operation.

The control system leverages spike trains – discrete, asynchronous pulses of information – as the primary means of communication, mirroring the efficiency of biological nervous systems. This approach, central to Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), allows for remarkably robust and energy-efficient data transfer; information is encoded not in the rate of firing, but in the timing of individual spikes. Consequently, the system is less susceptible to noise and offers significant computational advantages, particularly in power consumption, compared to traditional control architectures relying on continuous signals. By representing and processing information with these event-driven spike trains, the robot achieves a more streamlined and resilient control loop, contributing to its adaptability and performance in dynamic environments.

The development of this robotic control framework promises a new generation of machines capable of thriving in unpredictable real-world scenarios. Demonstrations reveal a substantial capacity for resilience and precision; the system consistently achieves a remarkable 97% success rate when navigating within a defined velocity range of 0.7 to 0.9 meters per second. Even when challenged with a broader velocity spectrum – from 0.7 to 1.5 m/s – performance remains high, registering a 93% success rate. This level of adaptability isn’t merely about speed, but represents a significant step towards robots that can learn and adjust to changing conditions, conserve energy through optimized movements, and operate reliably in complex, dynamic environments – ultimately blurring the lines between pre-programmed behavior and genuine environmental responsiveness.

The pursuit of robotic control through neuromorphic systems, as demonstrated in this work, reveals a fundamental truth about complex systems. It isn’t about imposing rigid control, but fostering adaptation. Donald Davies observed, “The best systems are those that tolerate failure.” This principle resonates deeply with the presented research; the DYNAP-SE chip, a small-scale analog-digital network, doesn’t strive for flawless execution, but for robust learning through spiking reinforcement learning. The chip’s ability to learn air hockey, despite the inherent unpredictability of the game, isn’t a testament to precise engineering, but to an emergent behavior arising from a network designed to evolve. Long stability, indeed, would be a misleading indicator; the system’s true strength lies in its capacity to transform and respond, much like a natural ecosystem.

What’s Next?

This demonstration, predictably, exposes more questions than it answers. The successful marriage of spiking networks and reinforcement learning on custom silicon isn’t a destination; it’s a particularly well-lit dead end. The architecture functioned, yes, but every deploy is a small apocalypse. Scaling this system-increasing neuron counts, task complexity, or operating in truly unstructured environments-will inevitably reveal the brittleness inherent in any hand-crafted intelligence. The current chip’s limitations aren’t merely engineering hurdles; they are prophecies of future failure, etched in transconductance.

The field now faces a choice. One path leads toward ever-more-complex architectures, chasing performance metrics with diminishing returns. The other, more interesting, path acknowledges that intelligence isn’t built – it grows. Future work must focus less on neuron count and more on the developmental processes that shape these networks. How can one create silicon ecosystems, capable of self-organization and adaptation, rather than merely programming increasingly elaborate reflexes?

Documentation, of course, will be sparse. No one writes prophecies after they come true. The true measure of success won’t be air hockey scores, but the ability to relinquish control, to build systems that surprise even their creators. That’s a thought that keeps most architects awake at night.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21548.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Overwatch Domina counters

- Brawl Stars Brawlentines Community Event: Brawler Dates, Community goals, Voting, Rewards, and more

- eFootball 2026 Starter Set Gabriel Batistuta pack review

- 1xBet declared bankrupt in Dutch court

- Clash of Clans March 2026 update is bringing a new Hero, Village Helper, major changes to Gold Pass, and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Bikini-clad Jessica Alba, 44, packs on the PDA with toyboy Danny Ramirez, 33, after finalizing divorce

- James Van Der Beek grappled with six-figure tax debt years before buying $4.8M Texas ranch prior to his death

2026-01-31 15:56