Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a formal method for abstracting complex causal relationships, offering a way to learn simplified causal models from real-world data.

This work introduces a framework for coarsening causal Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) with guarantees for identifiability from interventional data and a practical refinement algorithm.

While causal discovery often focuses on fine-grained relationships, practical applications frequently require abstract representations of complex systems. This paper, ‘Coarsening Causal DAG Models’, addresses this need by introducing a formal framework for systematically simplifying directed acyclic graphical (DAG) models through a process of causal abstraction. We provide both theoretical guarantees for identifiability under intervention and a provably consistent algorithm for learning these coarser graphs from interventional data, even with unknown intervention targets. Could this approach unlock more robust and interpretable causal models for real-world applications with limited or noisy data?

From Complexity to Clarity: Why We Need to Simplify

The pursuit of understanding causal relationships frequently relies on the construction of Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), where nodes represent variables and arrows depict direct causal effects. However, as systems grow in complexity – incorporating numerous interacting components – these DAGs rapidly become unwieldy. The number of potential connections, and therefore the computational burden of analyzing them, increases factorially with each added variable. This exponential growth quickly renders traditional analytical methods impractical, even with powerful computing resources. Consequently, researchers often encounter a ‘curse of dimensionality’, where the sheer scale of the DAG prevents effective inference about the underlying causal mechanisms, highlighting the need for techniques to manage this complexity.

Causal inference often grapples with the sheer complexity of real-world systems, necessitating a technique known as abstraction. This approach simplifies analysis by representing numerous individual variables as fewer, higher-level concepts. Rather than meticulously tracking each component, abstraction allows researchers to focus on broader patterns and relationships. Imagine, for instance, analyzing traffic flow – instead of monitoring every vehicle, one might abstract to ‘traffic density’ as a single variable. This reduction in complexity isn’t merely about convenience; it’s a fundamental strategy for making causal analysis computationally feasible and for identifying the core drivers of a system’s behavior. However, the effectiveness of abstraction hinges on carefully determining which variables to group, ensuring that essential causal connections aren’t obscured in the process of simplification.

The practical application of causal abstraction hinges on intelligently selecting which variables to consolidate, a process fraught with potential pitfalls. While simplifying a complex system is the goal, an ill-considered grouping of variables can inadvertently obscure vital causal pathways. This masking effect occurs when variables that, though seemingly related, actually transmit distinct causal influences; lumping them together erases these nuances. Consequently, the abstracted model may yield misleading conclusions about the system’s behavior, offering a distorted view of cause and effect. Therefore, the challenge isn’t simply to reduce complexity, but to do so while rigorously preserving the essential structure of causal relationships, demanding careful consideration of the potential consequences of each abstraction step.

Successfully simplifying complex systems with Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) hinges on the development of systematic coarsening methods. Simply grouping variables isn’t enough; the process must actively preserve the essential causal relationships within the original network. Researchers are exploring algorithms that identify variable clusters based on their causal connectivity – effectively collapsing strongly linked nodes while ensuring that no critical pathways are inadvertently obscured. This involves not only minimizing information loss during the abstraction process but also quantifying the remaining uncertainty introduced by the coarsening. The goal is to create higher-level representations that are both computationally manageable and still accurately reflect the underlying causal structure, allowing for robust inference even with limited data or computational resources.

Interventional Coarsening: A Principled Approach to Abstraction

Interventional Coarsening establishes a formal abstraction method predicated on grouping variables exhibiting equivalent responses to defined interventions – deliberate alterations to the system’s state. This differs from traditional abstraction techniques by explicitly considering the impact of external manipulations. The process identifies variables which, when subjected to the same intervention, produce identical or proportionally related changes in their values. By clustering these variables, the system’s complexity is reduced without losing fidelity to external causal effects. This approach ensures that the abstracted model accurately reflects the system’s behavior under controlled influence, making it suitable for causal inference and control design.

Interventional Coarsening simplifies a system’s representation by grouping variables that respond identically to the same external interventions. This means if two variables, X_i and X_j, consistently exhibit the same change in value following a specific intervention on another variable, they are considered functionally equivalent for that intervention and can be represented by a single, aggregated variable. This aggregation reduces the complexity of the model without losing information about the system’s response to deliberate manipulations, as the coarser variable accurately reflects the combined effect of the original variables under intervention. The process relies on identifying such consistent behavioral patterns across multiple interventions to determine which variables are suitable for grouping.

The determination of variable groupings in Interventional Coarsening hinges on the definition of an Intervention Descendant Signature. This signature, for a given node within a causal graph, is the complete set of interventions – deliberate manipulations applied to parent nodes – that demonstrably alter the value of that node or any of its descendants. Nodes sharing identical Intervention Descendant Signatures are considered functionally equivalent with respect to external manipulations and are therefore eligible for grouping into a single, coarser variable. The signature effectively captures a node’s responsiveness to interventions, providing a formal criterion for identifying variables that can be abstracted without losing information about the system’s causal behavior.

Preservation of causal effects under intervention is achieved by basing variable grouping on intervention descendants. This means that variables are only aggregated if they share the same set of nodes affected by a given intervention. Specifically, if two variables, X and Y, have identical intervention descendant signatures – meaning that applying the same intervention do(X=x) results in the same set of nodes being affected in both variables – then they can be safely represented by a single coarser variable without altering the predicted outcomes of external manipulations. This approach guarantees that the abstracted model accurately reflects the causal relationships present in the original system, as the effects of interventions are maintained at the coarser level of representation.

Refining the Partition: Statistical Methods for Coarsening

Partition Refinement is an iterative process used to group variables identified as intervention descendants based on statistical similarity. The algorithm begins with an initial partition – often each variable constituting its own individual group. Subsequent iterations evaluate the statistical dependence between groups; if variables within a group exhibit significantly different responses to interventions compared to variables in other groups, the group is split. Conversely, if variables in different groups demonstrate statistically indistinguishable responses, those groups are merged. This splitting and merging continues until a pre-defined stopping criterion is met, resulting in a partition where variables within each group share similar intervention effects, and differences between groups are statistically significant. The objective is to create a coarsened representation of the variable set, reducing complexity while retaining essential causal information.

Partition refinement employs statistical tests to quantify the difference in effects resulting from interventions on various variables; the Welch T-Test is utilized to compare the means of two groups, accounting for potentially unequal variances and sample sizes t = \frac{\bar{x}_1 - \bar{x}_2}{s_p \sqrt{\frac{1}{n_1} + \frac{1}{n_2}}} , where \bar{x} denotes the sample mean, s_p is the pooled standard deviation, and n represents the sample size. A statistically significant difference, as determined by a chosen significance level (e.g., α = 0.05), suggests that the variables respond differently to the intervention and should remain in separate partitions; conversely, a non-significant difference indicates potential for coarsening by merging the variables into a single group. The selection of the Welch T-Test is motivated by its robustness to violations of the assumption of equal variances, which is common in causal discovery scenarios.

Partition refinement achieves an optimal level of coarsening by iteratively assessing statistical similarity between intervention descendants and adjusting variable groupings accordingly. This process balances the desire for a simplified causal representation – reducing the number of variables – with the need to retain critical causal information. The algorithm systematically applies statistical tests to quantify the effects of interventions on each variable; significant differences indicate a need for further partitioning, while non-significant differences suggest variables can be merged without substantial loss of information. This iterative approach continues until a partition is reached where further refinement does not meaningfully improve the preservation of causal effects, effectively identifying a balance between model simplicity and accuracy.

The developed algorithm exhibits both identifiability and scalability characteristics crucial for practical application. Identifiability is guaranteed under specified conditions, ensuring the algorithm consistently recovers the true underlying causal structure. Computational complexity is quantified as O(edn + d²e + k²(p²n + p³)), where ‘e’ represents the number of edges in the causal graph, ‘d’ is the maximum degree of any node, ‘k’ is the number of partitions, ‘p’ denotes the number of variables, and ‘n’ is the sample size. This complexity indicates that the algorithm’s runtime grows polynomially with the size of the causal graph and the dataset, facilitating its application to moderately large-scale problems.

Evaluating Abstraction Quality: Likelihood and the Causal Abstraction Poset

Assessing the effectiveness of any abstracted model requires a quantifiable metric, and the Likelihood Heuristic provides just that – a scoring system based on explanatory power. This approach evaluates different levels of model simplification, or ‘coarsening’, by measuring how well each abstracted representation accounts for the observed data. Essentially, the heuristic posits that a ‘good’ abstraction is one that doesn’t drastically reduce the probability of seeing the data that was actually collected. Probabilistic models, such as Gaussian Chain Graphs, are employed to formally estimate this likelihood, allowing for a comparative analysis of different abstractions and enabling the selection of a model that balances simplicity with fidelity to the original system. This scoring facilitates a data-driven approach to abstraction, moving beyond purely intuitive judgments of model quality.

Evaluating the quality of an abstracted model requires a method for quantifying how well the simplification represents the original system, and this is achieved by leveraging probabilistic models such as Gaussian Chain Graphs. These graphs allow researchers to estimate the likelihood of observing the available data given the abstracted system’s structure. By representing relationships between variables with probabilistic dependencies, the model can assess how plausible the abstracted representation is in explaining the observed phenomena. A higher likelihood score indicates a better fit between the abstracted model and the data, suggesting a more accurate and useful simplification of the original complexity. This probabilistic approach moves beyond simple structural comparisons and provides a nuanced evaluation grounded in the data itself, allowing for a more robust determination of abstraction quality.

The totality of possible abstractions for a given system isn’t random; instead, these abstractions organize into a structured hierarchy known as a Causal Abstraction Poset. This poset represents a partially ordered set, meaning that each level within the hierarchy signifies a distinct degree of coarsening – from very fine-grained representations retaining considerable detail, to highly abstracted views focusing on broad system behaviors. Crucially, the ordering isn’t arbitrary; one abstraction is ‘below’ another if it can be obtained by refining, or ‘un-coarsening’, the higher-level abstraction. This structure allows for systematic exploration of the trade-off between model complexity and explanatory power, enabling researchers to navigate the abstraction space and identify representations that best suit the intended analytical goals – moving from general principles down to specific details, or vice versa, in a logically consistent manner.

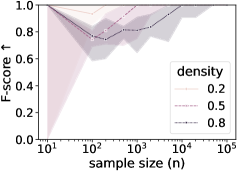

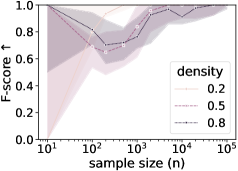

Rigorous testing using synthetically generated datasets reveals a strong correlation between abstraction quality and the volume of available data. Specifically, the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), a metric for assessing the similarity between partitions, consistently increases as the sample size grows, demonstrating an enhanced ability to accurately recover the underlying groupings within the data. Complementing this, the F-score-a measure of precision and recall in edge recovery-also exhibits a positive trend with increasing sample size, indicating that the abstracted model more reliably captures the essential relationships present in the original system. These findings suggest that, while the proposed abstraction methods are effective, their performance is significantly bolstered by larger datasets, reinforcing the importance of data quantity in achieving accurate and meaningful model simplification.

The pursuit of elegant causal models, as outlined in this work on coarsening DAGs, invariably leads to compromise. The formal framework for abstraction, while theoretically sound, acknowledges the messy reality of interventional data. It’s a refinement process, not a purification. As Hannah Arendt observed, “The point of life is not to prolong it, but to intensify it.” This paper doesn’t seek to create perfect causal representations, but rather to create usable ones, even if that means accepting a degree of coarsening. The partition refinement lattice, in essence, is a map of lost fidelity-a record of what was deemed non-essential for the model to survive deployment. Everything optimized will one day be optimized back, and this work anticipates that inevitable return.

What’s Next?

This formalization of coarsening causal diagrams is, predictably, a step toward making causal discovery tractable. The guarantees of identifiability under intervention are neat, certainly, but any system that claims to know what remains true after abstraction is merely postponing the inevitable. The partition refinement lattice provides a convenient structure, but the real world doesn’t politely present itself as a lattice. It fractures. The algorithm will find its limits, not through theoretical failure, but through the sheer volume of uncooperative data.

The inevitable next step involves tackling the messiness of partial interventions – the interventions that almost isolate a causal effect. A guarantee for fully controlled settings is a start, but production systems rarely afford such luxuries. More pressingly, the framework sidesteps the question of meaningful abstraction. Reducing a DAG doesn’t inherently reveal which relationships matter; it merely simplifies. The field will likely pursue heuristics for selecting ‘important’ variables, each one a tacit admission that perfect abstraction is an illusion.

If a bug is reproducible, the system is stable; if a causal model remains identifiable after coarsening, it is merely less brittle. The pursuit of elegant theory is admirable, but the real challenge lies in building systems that degrade gracefully, and whose failures are at least predictable. Documentation, as always, remains a collective self-delusion.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10531.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2026-01-17 13:48