Author: Denis Avetisyan

A novel framework blends the principles of continuum mechanics and optimal transport to create more robust generative models, even with limited data.

![The system investigates data generation under incomplete states, aiming to define the relationship between features given knowledge of other states-a process akin to reconstructing a missing piece by understanding the connections within the whole [latex] \implies [/latex] a challenge in extrapolating function from partial observation.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.20462v1/x1.png)

This work introduces a Continuum Mechanistic Generative AI (CM-GAI) theory leveraging physics-informed neural networks for data-driven modeling in non-Euclidean spaces.

Despite the successes of generative artificial intelligence, data scarcity remains a significant limitation in specialized domains. This paper introduces ‘CM-GAI: Continuum Mechanistic Generative Artificial Intelligence Theory for Data Dynamics’, a novel framework that leverages continuum mechanics and optimal transport to enable robust data-driven generative modeling, even with limited training data. By formulating data dynamics as a transport problem in feature space and employing physics-informed neural networks for its solution, we demonstrate successful data generation across multiple scales-from material response to structural and system-level behaviors. Could this mechanics-informed approach unlock new capabilities in generative AI beyond traditional engineering applications, such as image synthesis and beyond?

Deconstructing Reality: The Dawn of Generative Intelligence

Generative Artificial Intelligence is swiftly reshaping diverse disciplines, extending far beyond entertainment and artistic expression to impact scientific discovery and technological innovation. This rapid transformation isn’t simply about automation; it’s fueled by an increasing demand for novel data – data that doesn’t yet exist. Traditional methods often struggle to provide the volume and variety of information needed for tasks like drug discovery, materials science, and advanced simulations. Generative AI offers a solution by creating synthetic data that mirrors real-world complexity, effectively augmenting limited datasets and accelerating research. From designing new proteins with specific properties to generating realistic training data for autonomous vehicles, the ability to produce original, high-quality data is proving to be a pivotal advantage, pushing the boundaries of what’s possible across numerous fields and signaling a new era of data-driven innovation.

Generative models represent a significant shift in artificial intelligence, moving beyond simply recognizing patterns to actively creating new data that mirrors the complexity of the input they’ve learned from. These models don’t just memorize; they statistically deconstruct data – be it images, text, or music – to understand the relationships between its components. By identifying these underlying structures, a generative model can then sample from this learned representation, effectively ‘imagining’ new instances that are statistically similar to the original data. This process allows for the creation of realistic outputs, ranging from photorealistic images of non-existent people to original musical compositions, demonstrating a capacity for creativity previously thought exclusive to biological intelligence. The power of these models lies in their ability to capture the essence of a dataset and extrapolate, generating novel content that is both coherent and convincingly real.

Generative models, the engines behind artificial intelligence’s creative surge, operate on a foundational principle: the comprehension and replication of probability distributions. These models don’t simply memorize training data; instead, they learn the statistical relationships within it, essentially building an internal map of how likely different outcomes are. For example, when generating an image of a cat, the model understands that certain pixel arrangements – whiskers, ears, a furry texture – are far more probable than others. This understanding is mathematically represented as [latex]P(x)[/latex], the probability of observing a particular data point [latex]x[/latex]. By accurately capturing this distribution, the model can then sample from it, creating new data points – images, text, music – that share the characteristics of the original training data but are entirely novel. The sophistication of a generative model often hinges on its ability to represent increasingly complex and high-dimensional probability distributions, allowing for the creation of remarkably realistic and diverse outputs.

Beyond Mimicry: Imposing Order on Chaos

Conventional generative models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), often produce outputs that violate fundamental physical principles, resulting in unrealistic or implausible data. These inconsistencies arise because these models primarily focus on statistical similarity to training data without explicitly enforcing physical constraints. Consequently, generated samples may exhibit impossible geometries, unnatural material properties, or violate established laws of motion. A more reliable approach to data generation involves integrating governing physical laws directly into the model architecture or loss function. This ensures that the generated data adheres to known physical rules, leading to more realistic, stable, and predictable outputs, particularly in domains like fluid dynamics, material science, and robotics where physical fidelity is paramount.

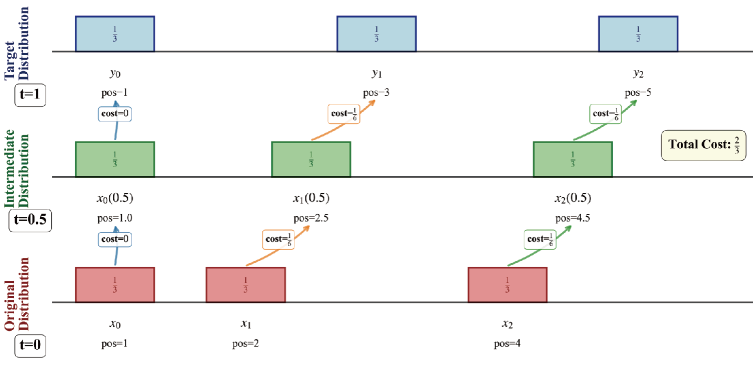

Optimal Transport (OT) provides a formalized method for comparing and mapping probability distributions, treating data generation as the process of transforming one distribution to another with minimal “cost”. Mathematically, OT seeks to find the optimal transport plan – a mapping – that minimizes the total cost of transporting “mass” from a source distribution [latex]P[/latex] to a target distribution [latex]Q[/latex], based on a defined cost function [latex]c(x, y)[/latex] representing the cost of moving mass from point [latex]x[/latex] to point [latex]y[/latex]. This framework moves beyond simple statistical matching by establishing a geometric structure on the space of probability distributions, allowing for the calculation of distances (the Wasserstein distance) and the modeling of data generation as a physical transport process governed by energy minimization principles. The resulting methodology is applicable to a range of generative tasks, including image synthesis, domain adaptation, and anomaly detection, by providing a rigorous way to ensure consistency and control over the generated outputs.

The application of Optimal Transport for generative modeling intrinsically leverages principles from Continuum Mechanics to manipulate data within its feature space. This is achieved by treating the generated data distribution as a continuous medium subject to deformation and interaction governed by mechanical laws. Specifically, the cost functions used in Optimal Transport calculations can be interpreted as energy densities, and the transport plan represents a deformation field mapping one distribution to another. Consequently, concepts like stress, strain, and elasticity become relevant when analyzing and controlling the generative process, enabling the simulation of realistic physical behaviors and interactions within the generated output. [latex] \nabla \cdot \sigma = f [/latex] , a fundamental equation in Continuum Mechanics, finds parallels in the optimization process of finding the minimal cost transport plan.

Architectures for Manifesting Reality

Generative modeling is currently experiencing growth with the development of multiple approaches. Diffusion Models generate data by progressively adding noise and then learning to reverse this process, enabling the creation of high-fidelity samples. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) utilize neural networks to encode data into a latent space and then decode it to reconstruct the original input, allowing for data generation through sampling from this latent space. Both model types rely on probabilistic frameworks and gradient-based optimization techniques for training, and are frequently applied to image, audio, and text generation tasks, demonstrating varying degrees of success depending on the complexity of the data and the specific network architecture employed.

Flow-based models generate data by learning a series of invertible transformations that map a simple probability distribution, such as a standard Gaussian, to the data distribution. This approach differs from other generative models as it allows for exact likelihood computation; given a data point, the model can precisely determine its probability density. The invertibility of the transformations is crucial, enabling both generation – sampling from the simple distribution and transforming it to the data space – and density estimation by applying the inverse transformation and calculating the Jacobian determinant. Unlike models relying on Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods for likelihood approximation, flow-based models provide a direct and computationally efficient means of evaluating the probability of observed data.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) enhance generative model outputs by directly incorporating known physical laws and constraints into the network’s learning process. This approach differs from traditional data-driven methods and allows for solutions even with limited training data. The accuracy of PINN-based solutions can be quantitatively compared to established numerical methods like the Finite Element Method (FEM); our CM-GAI implementation demonstrates high performance in benchmark problems, achieving Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) values of 0.56% and 1.10% depending on the specific problem tested. These results indicate a strong correlation between CM-GAI predictions and established FEM solutions, validating the efficacy of the physics-informed approach.

Navigating Complexity: Beyond Euclidean Constraints

The escalating complexity of modern datasets often presents a significant challenge known as the ‘curse of dimensionality’, where the number of features vastly exceeds the number of samples. This phenomenon hinders effective data analysis and modeling, as algorithms struggle with computational cost and the risk of overfitting. To mitigate this, dimensionality reduction techniques become crucial; these methods aim to represent data in a lower-dimensional space while preserving essential information. Approaches like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identify key patterns and project data onto a reduced set of uncorrelated variables, while techniques like t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) focus on preserving local data structure for visualization. By intelligently reducing the number of dimensions, these methods not only improve computational efficiency but also enhance the performance and interpretability of machine learning models, allowing for more robust and insightful data analysis.

Conventional data analysis often assumes a Euclidean space – a system where the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. However, many real-world datasets defy this simplicity, exhibiting intricate relationships better captured by non-Euclidean geometries. Exploring these alternative spaces, such as hyperbolic or spherical geometries, allows for more nuanced data representation, particularly when dealing with hierarchical data, networks, or complex relationships. For instance, in network analysis, representing connections on a curved space can more accurately reflect the inherent structure and distances between nodes. This approach enables algorithms to identify patterns and make predictions with greater accuracy, as the geometric properties of the space align more closely with the underlying data distribution, overcoming limitations imposed by the strict linearity of Euclidean space and unlocking insights hidden within high-dimensional datasets.

Auto-regressive models, exemplified by Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), build upon dimensionality reduction and non-Euclidean space concepts to achieve remarkable feats in natural language processing. These models function by predicting the next element in a sequence – be it a word, a pixel, or a note – based on all preceding elements. This sequential prediction isn’t merely about memorization; it involves learning a complex probability distribution over vast datasets, effectively creating a high-dimensional representation of language itself. The ‘transformer’ architecture, crucial to GPT’s success, utilizes attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence, allowing the model to capture long-range dependencies and contextual nuances. Consequently, these models don’t just process text; they generate coherent, contextually relevant text, translate languages, and even answer questions with a level of sophistication previously unattainable, demonstrating a powerful extension of techniques designed to navigate and understand complex data landscapes.

The Looming Synthesis: A Future Forged in Physics

The evolution of generative artificial intelligence is increasingly reliant on a synthesis of data-driven learning and established physical principles. While purely data-driven models excel at pattern recognition, they often struggle with generalization and physical plausibility, particularly when extrapolating beyond the training dataset. Integrating physics-based models provides a crucial framework for enforcing realistic constraints and improving the robustness of generated outputs. This hybrid approach allows algorithms to not only learn from data but also to understand the underlying physical laws governing the system, leading to more accurate, efficient, and interpretable results. Consequently, future advancements in fields like materials science, engineering, and climate modeling will depend heavily on this convergence, enabling the creation of AI systems capable of designing novel materials, predicting complex phenomena, and optimizing performance with unprecedented fidelity.

Hamilton’s Principle, a cornerstone of physics stating that the path a system takes minimizes its action, is increasingly recognized as a potent framework for building generative algorithms. Rather than relying solely on extensive datasets, these algorithms leverage the inherent constraints dictated by physical laws, ensuring generated outputs are not only plausible but fundamentally stable and efficient. This approach moves beyond simply imitating physical phenomena; it embodies them within the generative process itself. By framing the generation task as an optimization problem governed by [latex]S = \in t L \, dt[/latex] – where [latex]S[/latex] represents the action, [latex]L[/latex] the Lagrangian, and [latex]t[/latex] time – algorithms can produce solutions that adhere to conservation laws and exhibit realistic behavior, even with limited training data. This has significant implications for fields requiring high fidelity and physical consistency, promising a new era of robust and data-efficient generative modeling.

The convergence of data-driven artificial intelligence and established physics-based modeling offers transformative potential across diverse scientific domains. A novel approach, termed CM-GAI, exemplifies this synergy by achieving remarkably accurate predictions-with limited training data-in complex simulations. Specifically, CM-GAI demonstrates predictive power in modeling temperature-dependent stress fields, achieving a Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) of just 0.56%, and accurately predicting plastic strain fields with an NRMSE of 1.10%. This capability suggests that bridging the divide between data and fundamental physical principles will not only accelerate progress in materials design and discovery, but also enable more robust and reliable climate modeling, and ultimately, a new era of scientific simulation.

![CM-GAI predictions align closely with those generated by the Guo et al. model [21], demonstrating comparable performance.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.20462v1/x29.png)

The presented work embodies a spirit of intellectual deconstruction. It doesn’t simply accept existing generative models; instead, it dissects their limitations – particularly the need for extensive datasets – and proposes a fundamentally different approach. This aligns perfectly with the sentiment expressed by Ada Lovelace: “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything.” This research doesn’t originate data, but rather skillfully manipulates and transports existing probability distributions within feature spaces, leveraging the principles of continuum mechanics and optimal transport. By solving the resulting transport problem with physics-informed neural networks, the framework demonstrates a profound understanding of the underlying mechanics of data generation – effectively reverse-engineering the process itself. The core idea of transporting probability distributions showcases a commitment to analyzing and re-interpreting existing concepts, not merely accepting them.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The presented framework, while elegantly bridging continuum mechanics and generative AI, inevitably highlights what remains stubbornly resistant to modeling. The reliance on optimal transport, though powerful, assumes a certain smoothness in the underlying data manifold – a convenient fiction frequently violated by real-world complexity. Future work must confront the inherent messiness of data, exploring transport schemes robust to discontinuities and high-dimensionality. The current methodology implicitly treats data as a continuous substance; investigations into granular or discrete representations could reveal entirely new generative pathways.

A particularly intriguing, if uncomfortable, avenue lies in loosening the constraints of physics-informed neural networks. The insistence on satisfying physical laws, while laudable, may inadvertently bias the generative process, preventing the discovery of genuinely novel data distributions. What if the most interesting data doesn’t adhere to known physics? Perhaps the true power of this approach will only be unlocked by deliberately introducing controlled violations of the governing equations, observing the resulting instabilities, and learning from the failures.

Ultimately, this work isn’t about building better models; it’s about refining the questions. The real challenge isn’t replicating existing data, but anticipating what data should exist – a task that demands a willingness to abandon assumptions and embrace the beautifully unpredictable nature of reality.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20462.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Genshin Impact Version 6.5 Leaks: List of Upcoming banners, Maps, Endgame updates and more

- Overwatch Domina counters

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

2026-01-30 04:35