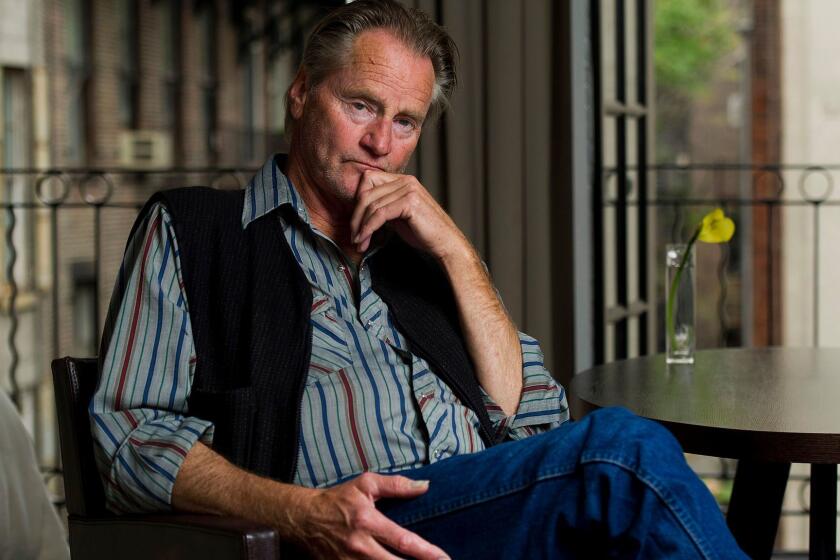

In 1967, as his career was beginning to take off off-Broadway, Sam Shepard bluntly told Newsweek that theater was failing because no one was willing to take risks. This was a surprising comment from a man who generally shied away from publicity and often doubted himself. However, as Robert M. Dowling shows in his biography, “Coyote,” Shepard was a complex figure. His life wasn’t simply a series of contradictions; it was a complicated mix of frustration, setbacks, and self-destructive tendencies, alongside his achievements in theater and film.

I have to say, Dowling’s portrayal of Sam Shepard really captures this incredible talent who made it all look effortless. The guy was an EGOT nominee – Oscar, Emmy, Tony – and racked up a ton of other awards, including a Pulitzer Prize for ‘Buried Child’ back in ’79. What struck me was learning about his upbringing – born in 1943, he was raised by a tough, decorated WWII veteran in California. That really seemed to fuel his lifelong fascination with American power and what it means to be a man. He quickly left home for New York in the early sixties and practically exploded onto the off-Broadway scene, clearly inspired by playwrights like Beckett and Albee and all that experimental energy.

Sam Shepard’s early talent was questionable. Even one of his first teachers thought his initial scripts were disorganized. His 1967 play, “La Turista,” was controversial, featuring onstage chicken decapitations that drew protests from animal rights groups. While audiences at Lincoln Center weren’t impressed, Shepard received support from influential writers at publications like the New York Review of Books and Village Voice, and the experimental theater scene allowed him the space to develop his unique style.

Dowling’s book presents Sam Shepard as a representative figure of American culture at the end of the 20th century, reflecting how the rebellious spirit of the 1960s softened into the more subtle influences of the 1980s and 90s. Early in his career, Shepard strongly criticized traditional values of the Vietnam era, favoring the countercultural scene of the Bay Area over what he described as the chaotic sprawl of Los Angeles. However, he was also gradually becoming more accepted by mainstream culture, sometimes reluctantly. Connections with Bob Dylan and emerging filmmakers like Terence Malick helped raise his profile, and a short, intense romance with Joni Mitchell, which she later wrote about in her song “Coyote,” further cemented his place in the cultural landscape.

Author Dowling, known for a previous biography of Eugene O’Neill, skillfully explores the complex life of Sam Shepard – a man of many sides, including a rural upbringing, successful playwriting career, and various personal relationships. Dowling acknowledges Shepard’s struggles with alcohol, which significantly impacted his later years, damaging friendships, romances, and his creative work. The biography draws on Shepard’s extensive body of work – his plays, stories, and essays – and features honest perspectives from those who knew him well, such as Johnny Dark and Ethan Hawke. Notably, it does not include input from Shepard’s ex-wife, O-Lan Jones, or his long-term partner, Jessica Lange.

Entertainment & Arts

Eugene O’Neil brought gravitas to the American theater.

Sam Shepard’s success in the 1980s felt overwhelming, like a sudden rush of attention, says critic Ben Dark. He became widely known through powerful plays focusing on family struggles, such as “Buried Child” and “Fool for Love.” His play “True West” also helped launch the Chicago-based Steppenwolf Theatre Company to national prominence. A 1984 public television revival of “True West,” starring John Malkovich and Gary Sinise (who originally performed it with Steppenwolf), is available to watch online and remains compelling. Through his work, Shepard openly explored difficult family dynamics, tackling themes of toxic masculinity with unusual insight and passion, ultimately aiming to redefine what a ‘family drama’ could be.

Dowling clearly demonstrates Shepard’s rise to prominence and his eventual decline before his death in 2017. However, the book doesn’t fully explain why Shepard’s work resonated so strongly with audiences and critics at the time. Dowling focuses more on how people reacted to Shepard’s plays than on the plays themselves. This is a key oversight, considering Shepard’s almost compulsive need to write – he even began drafting his 1993 play, “Simpatico,” while driving! Including examples of the distinctive, often tough, dialogue from plays like “True West” and “Buried Child” would have helped to illustrate what made Shepard such a unique and powerful writer.

Understanding Shepard’s role within the broader theater world would add valuable context. While Shepard eventually gained international recognition – especially in Ireland, where he was seen as a successor to Samuel Beckett – he wasn’t alone in exploring themes of family and masculinity. Though contemporaries like David Mamet and August Wilson are only briefly mentioned, Shepard largely appears disconnected from the American theater community, aside from a single instance of mentoring Lynn Nottage. This isolation contributed to his unique voice, but it might make him seem less original and more simply alone.

Perhaps the image of “Coyote,” as Shepard presented it, leaned too heavily into the classic American archetype of the solitary, brilliant man – a figure he both utilized and challenged in his work. He cultivated a persona of casual indifference, famously telling a reporter he’d simply write something else if people didn’t understand his art. However, as his health declined due to muscular atrophy, that carefully constructed image began to fall apart. He desperately wanted to reconnect with an old friend, Dark, but Dark, worn down by years of Shepard’s difficult behavior and struggles with alcohol, had passed away. Dowling reports Dark’s dismissive comment, and Shepard echoed it with the same harsh words. It’s a raw, powerful moment – the kind of material a playwright could have built an award-winning play around.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Books

Understanding Sam Shepard’s work is challenging mainly because it’s hard to map out and define his artistic boundaries.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash of Clans January 2026: List of Weekly Events, Challenges, and Rewards

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

2025-11-04 14:33