Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework allows robots to acquire complex manipulation skills simply by observing human demonstrations in video, bypassing the need for time-consuming and expensive robot-specific training.

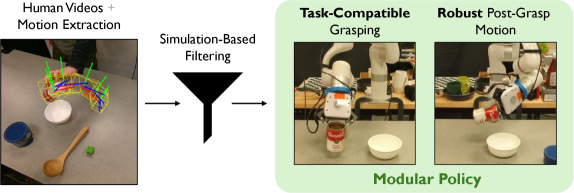

Researchers demonstrate a simulation-filtered modular policy learning approach, enabling robots to learn task-compatible grasping from human videos and achieve sample-efficient cross-embodiment learning.

Learning complex manipulation skills remains a challenge for robots, despite the potential of leveraging the vast amount of demonstration data available in human videos. This work, ‘Imitating What Works: Simulation-Filtered Modular Policy Learning from Human Videos’, introduces a novel framework, Perceive-Simulate-Imitate (PSI), that enables robots to learn directly from human demonstrations by filtering trajectories in simulation to identify task-compatible grasps. By extending video data with grasp suitability labels, PSI facilitates efficient supervised learning of manipulation policies without requiring robot-specific data. Could this approach unlock a new paradigm for cross-embodiment learning and significantly accelerate the development of more versatile and adaptable robotic systems?

Beyond Mimicry: The Limits of Robotic Dexterity

Robotic manipulation, despite decades of advancement, consistently falls short of the effortless dexterity demonstrated by human hands. Unlike robots typically reliant on precise, pre-programmed movements, people seamlessly adapt to unforeseen variations in object shape, weight, and fragility. This human capability stems from a complex interplay of sensory feedback, nuanced motor control, and learned strategies for grasping and manipulating a vast range of items. Traditional robotic grippers often struggle with unpredictable environments or objects lacking clearly defined grasping points, leading to failed attempts or even damage. The challenge isn’t simply replicating the motion of a hand, but also achieving the same level of adaptable, robust, and intuitive control – a feat requiring significant breakthroughs in sensing, artificial intelligence, and materials science.

Many robotic manipulation systems currently function with a significant limitation: reliance on meticulously pre-programmed movement sequences or a severely restricted comprehension of their surroundings. This approach, while sometimes effective in highly structured environments, dramatically reduces performance when faced with even slight variations or unforeseen obstacles. Because these systems lack the capacity to dynamically adapt to new information, a simple change in object position, lighting, or the introduction of an unexpected item can lead to failure. The result is a brittle performance, incapable of matching the fluid, adaptable dexterity demonstrated by human hands, which continuously integrate visual and tactile feedback to refine actions in real-time. Ultimately, this dependence on pre-planning restricts robots to narrowly defined tasks and hinders their potential in complex, real-world applications.

Achieving truly human-like robotic manipulation hinges on a system’s ability to not merely see an environment, but to comprehensively understand it – discerning objects, their relationships, and potential interactions. This necessitates advanced perception systems that go beyond simple object recognition, incorporating contextual awareness and predictive modeling. A robot must infer not only what is present, but also how it can be manipulated – anticipating the effects of actions and adapting to unexpected changes in the scene. Such inference requires integrating visual data with tactile sensing and potentially other modalities, creating a rich internal representation of the environment that guides dexterous and robust manipulation strategies. Ultimately, the challenge lies in bridging the gap between passive observation and active, intelligent intervention in complex, real-world scenarios.

Decoding the System: A Novel Framework for Robotic Learning

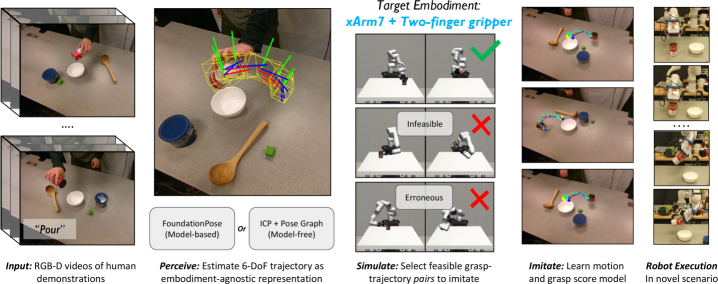

The Perceive-Simulate-Imitate (PSI) framework represents a novel approach to robotic learning by integrating three core components – perception, simulation, and imitation – to maximize learning efficiency. This paradigm moves beyond traditional methods by enabling robots to learn complex tasks from relatively limited human video data. Perception, achieved through techniques like 6D pose estimation, allows the robot to understand the current state of the environment and relevant objects. Simulation then provides a safe and computationally inexpensive environment for exploring potential actions and refining control policies. Finally, imitation learning leverages the human videos to guide the simulation process and accelerate the development of robust and effective robotic behaviors, resulting in significantly improved sample efficiency compared to methods relying solely on real-world interaction.

The Perceive-Simulate-Imitate (PSI) framework relies on 6D pose estimation to determine the position and orientation of objects within the robot’s environment. This estimation, providing x, y, and z coordinates alongside roll, pitch, and yaw angles, enables the robot to accurately model object states. Accurate perception of object pose is critical for subsequent simulation and imitation stages, as it provides the necessary input for predicting the effects of actions and learning from human demonstrations. The precision of 6D pose estimation directly impacts the fidelity of the simulated environment and the robot’s ability to generalize learned behaviors to novel situations.

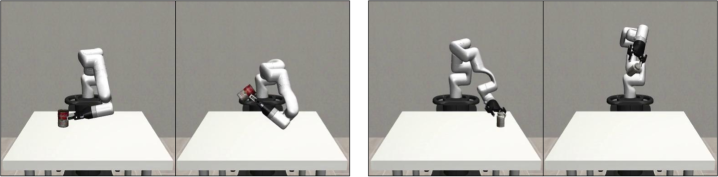

Robot simulation within the PSI framework enables the exploration of a significantly larger action space than is feasible in real-time interaction. This capability allows for the iterative refinement of robotic policies without incurring the risks associated with physical experimentation – such as potential damage to the robot or its environment – and bypasses the temporal limitations of real-world training. Consequently, the number of unsuccessful or erroneous trajectories experienced during the learning process is substantially reduced, leading to improved policy performance and increased sample efficiency. This accelerated learning is achieved by allowing the robot to virtually experience and correct mistakes in a safe and time-compressed environment before deployment in the physical world.

The Foundation of Sight: Accurate 6D Pose Estimation

Accurate 6D pose estimation-determining an object’s position in three-dimensional space (x, y, z) and its rotational orientation (roll, pitch, yaw)-is a fundamental requirement for robotic perception and scene understanding. This estimation enables robots to interact with objects precisely, facilitating tasks like grasping, manipulation, and assembly. The pose is typically represented as a homogeneous transformation matrix, combining both translational and rotational components. Achieving high accuracy in 6D pose estimation is challenging due to factors like occlusion, lighting variations, and sensor noise; however, precise pose data is critical for downstream applications including object recognition, path planning, and augmented reality integration within robotic systems.

Reliable 6D pose estimation is achieved through the combination of several established methodologies. FoundationPose utilizes a learned prior to initialize pose estimates, providing a robust starting point even with limited initial data. The Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm then refines this estimate by iteratively minimizing the distance between a source point cloud and a target surface. To improve robustness against noisy data and potential outliers, statistical outlier removal techniques, such as those based on distance thresholds or normal vector consistency, are applied either before or during the ICP process. This combination allows for accurate and consistent pose determination in a variety of conditions, forming a foundational component of robotic perception systems.

Integrating flow representation and general flow prediction improves robotic perception in dynamic environments by modeling the apparent motion of objects and scene elements. Flow representation utilizes optical flow, a pattern of apparent motion of image objects, to quantify movement between consecutive frames. General flow prediction extends this by learning to anticipate future flow fields, enabling the robot to not only perceive current motion but also predict the trajectory of objects. This predictive capability is crucial for tasks like interception, avoidance, and manipulation, allowing the robot to react proactively to changing scenes and maintain stable interactions with moving objects. The predicted flow data is typically represented as a dense vector field, indicating both the direction and magnitude of motion at each pixel, and can be integrated with other sensor data for robust state estimation.

Learning Through Observation: Demonstration and Simulation

Robot Learning from Demonstration (LfD) establishes an initial operational baseline by enabling robots to acquire skills through observation and replication of human behavior. This process typically involves a human demonstrator performing a task, with the robot recording relevant data such as joint angles, end-effector positions, and visual input. This recorded data is then used to train a policy, often employing techniques like supervised learning or imitation learning, which allows the robot to reproduce the demonstrated actions. The resulting policy provides a starting point for further learning and adaptation, reducing the need for extensive random exploration and accelerating the skill acquisition process. LfD is particularly effective in complex or high-dimensional action spaces where defining reward functions for reinforcement learning can be challenging.

Following acquisition of initial skills through learning from demonstration, robotic capabilities are extended via simulation-based refinement. This process allows robots to practice and generalize learned behaviors in a controlled, cost-effective environment, exploring scenarios not explicitly covered in the demonstration data. Through simulation, robots can accumulate experience at a rate exceeding real-world interaction, facilitating adaptation to novel situations and improving robustness to variations in environmental conditions. This simulated experience effectively augments the initial knowledge base, enabling performance beyond the limitations of the demonstrated examples and improving the robot’s overall task proficiency.

The efficacy of robot learning is substantially improved through the utilization of large-scale datasets and pretraining techniques. Methods like R3M and ImageNet pretraining provide a foundational understanding of visual concepts, accelerating the learning process and enhancing generalization to novel situations. Specifically, PSI pretraining, employing the HOI4D dataset-focused on human-object interaction-has demonstrated measurable performance gains across a range of robotic tasks. This approach allows robots to extrapolate beyond explicitly demonstrated examples by leveraging pre-existing knowledge of object affordances and interaction dynamics, resulting in more robust and adaptable behavior.

The Evolving Machine: Towards Adaptable Robotic Systems

Recent advances in robotics are converging perception, simulation, and imitation learning to unlock new levels of dexterity and adaptability in automated systems. Instead of relying on pre-programmed sequences, robots are now capable of learning complex manipulation skills by observing demonstrations, practicing in simulated environments, and refining their actions through real-world experience. This trifecta allows for robust performance even in unpredictable conditions; a robot can leverage its perceptual abilities to understand the environment, use simulation to anticipate outcomes and plan accordingly, and then employ imitation learning to replicate successful strategies. The result is a system capable of generalizing learned skills to novel objects and scenarios, marking a significant step towards truly versatile and autonomous robotic agents that can operate effectively in dynamic, real-world settings.

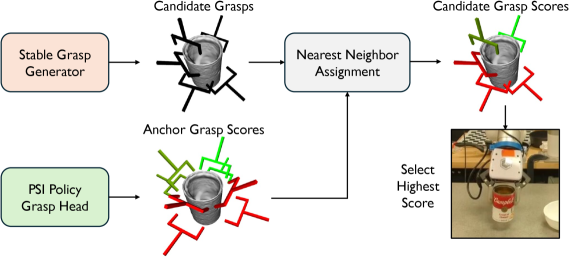

Robotic manipulation is becoming increasingly sophisticated through the development of modular policy designs and grasp scoring models. These approaches move beyond pre-programmed sequences, allowing robots to dynamically adapt to varying object shapes, sizes, and positions. Modular policies break down complex tasks into smaller, reusable components – such as reaching, grasping, and lifting – enabling robots to quickly assemble appropriate action plans for novel scenarios. Simultaneously, grasp scoring models evaluate the stability and feasibility of potential grasps, considering factors like contact points, force distribution, and object geometry. By combining these elements, robots can efficiently search for robust grasps, even in cluttered or uncertain environments, leading to more reliable and versatile manipulation capabilities. This framework not only enhances a robot’s ability to handle a wider range of objects, but also improves its resilience to disturbances and unexpected changes during task execution, paving the way for truly adaptable robotic systems.

Robotic systems are increasingly leveraging object-centric representation as a core component of task planning and execution. Rather than treating the environment as a continuous space, this approach focuses on identifying and modeling individual objects, their properties, and their relationships to one another. This allows for a more intuitive and efficient method of defining desired outcomes and generating feasible action sequences. Coupled with the strategic placement of waypoints – specific, reachable configurations in the robot’s workspace – complex tasks are broken down into manageable steps. The robot navigates to these waypoints while maintaining awareness of the objects involved, enabling robust performance even in dynamic or cluttered environments. This framework not only simplifies planning but also facilitates adaptability; by modifying waypoint configurations or object interactions, the robot can quickly respond to unforeseen circumstances and achieve its goals with greater reliability.

The research detailed in ‘Imitating What Works’ doesn’t simply accept the limitations of robotic learning; it actively challenges them. By leveraging simulation-based filtering, the PSI framework dissects human demonstrations, extracting viable trajectories and effectively reverse-engineering successful manipulation skills. This approach resonates deeply with the principle that understanding emerges from rigorous testing. As Barbara Liskov astutely observed, “Programs must be correct, but correctness is not enough; they must also be understandable.” PSI isn’t just replicating actions; it’s striving for an underlying, graspable model of how those actions achieve task-compatible grasping – a critical element for truly adaptable robotic systems. The system pushes the boundaries of prehensile manipulation by questioning established norms, revealing that even the most complex behaviors can be broken down and reassembled for robotic execution.

Beyond Mimicry

The framework presented doesn’t merely replicate observed actions; it attempts to distill the intent behind them, a subtle but crucial distinction. However, the simulation-to-reality gap remains a persistent irritant. While filtering trajectories in simulation offers a degree of robustness, it is ultimately a probabilistic patch. True cross-embodiment learning demands a deeper understanding of how physical constraints, not just visual cues, shape successful manipulation. The current work implicitly assumes a degree of kinematic similarity between the human demonstrator and the robot – a limitation that invites exploration of methods for bridging more substantial morphological differences.

One can anticipate a shift toward more active learning strategies. Rather than passively absorbing information from videos, future systems might intelligently query simulations – or even real-world environments – to resolve ambiguities and refine their understanding of task compatibility. This raises a fascinating question: how does one design a robotic ‘curiosity’ that prioritizes experiments likely to yield the most significant gains in manipulative dexterity? The answer, undoubtedly, lies in a more nuanced definition of ‘success’ than simply matching observed outcomes.

Ultimately, this work opens a pathway not toward perfect imitation, but toward a form of robotic pragmatism. The system doesn’t aim to be a human manipulator; it aims to achieve the same goals, using whatever means are available. This is a crucial distinction, and one that suggests a future where robots don’t simply follow instructions, but devise their own solutions – even if those solutions look nothing like the examples they were given.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.13197.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

- Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Trilogy Is Skipping Children of Dune

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Peppa Pig will cheer on Daddy Pig at the London Marathon as he raises money for the National Deaf Children’s Society after son George’s hearing loss

- Are Halstead & Upton Back Together After The 2026 One Chicago Corssover? Jay & Hailey’s Future Explained

2026-02-17 02:00