Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a reinforcement learning system that allows a humanoid robot to master the complex motor skills required for playing badminton, bridging the gap between simulation and real-world performance.

A progressive reinforcement learning framework enables zero-shot transfer of badminton skills from simulation to a physical humanoid robot, utilizing goal-conditioned reinforcement learning and adversarial motion priors.

Achieving truly versatile athletic performance remains a significant hurdle for humanoid robots, particularly in dynamic sports demanding precise timing and full-body coordination. This work, ‘Learning Human-Like Badminton Skills for Humanoid Robots’, introduces a progressive reinforcement learning framework-Imitation-to-Interaction-that evolves a robot from mimicking human movements to skillfully executing badminton strokes. By distilling expert data into a compact state representation, stabilizing dynamics with adversarial priors, and generalizing sparse demonstrations via manifold expansion, we demonstrate mastery of diverse skills like lifts and drop shots in simulation and, crucially, the first successful zero-shot transfer to a physical humanoid robot. Can this approach unlock similarly nuanced and adaptive athletic capabilities across a wider range of complex human sports?

The Illusion of Athleticism: Why Robots Still Can’t Play Badminton

The inherent dynamism of sports like badminton presents a significant challenge to traditional robotic control systems. Unlike pre-programmed industrial tasks performed in static environments, a badminton rally demands continuous adaptation to unpredictable ball trajectories and opponent actions. Existing control methods, often reliant on precise kinematic models and pre-defined trajectories, struggle to cope with the high velocities, rapid changes in direction, and subtle variations inherent in gameplay. Consequently, robotic systems attempting to replicate these skills require not just accurate movement execution, but also robust strategies for real-time perception, prediction, and adaptive control – demanding a level of flexibility and responsiveness that surpasses the capabilities of many conventional robotic platforms.

Attempts to directly transfer human badminton techniques to robotic systems frequently encounter limitations stemming from fundamental differences in physical structure. A robot, unlike a human athlete, possesses varying limb lengths, joint ranges, and mass distributions, rendering exact kinematic replication ineffective. Moreover, the dynamic nature of a badminton rally necessitates continuous adaptation to unpredictable ball trajectories and opponent actions; pre-programmed movements, even if accurately copied, lack the responsiveness required for successful gameplay. Consequently, a rigid adherence to human motion capture data proves insufficient, highlighting the need for robotic systems capable of learning and refining their movements through real-time feedback and iterative improvement, rather than simply mirroring human performance.

Automating a complex athletic maneuver like the badminton lift requires more than simply copying human motion; a synergistic approach combining learned imitation with reinforcement learning is essential for dynamic skill acquisition. Initial imitation learning provides a crucial starting point, allowing the robotic system to rapidly approximate a functional policy from expert demonstrations. However, the inherent differences between a robot’s morphology and a human athlete, coupled with the unpredictable nature of gameplay, necessitate continuous adaptation. Reinforcement learning steps in to refine this initial policy through trial and error, enabling the robot to optimize its performance based on real-time feedback and overcome the limitations of purely imitative strategies. This blended framework allows the system to not only reproduce the basic lift but also to generalize its capabilities, adjusting to varying shuttlecock trajectories and opponent actions – ultimately bridging the gap between pre-programmed movements and truly adaptive, athletic performance.

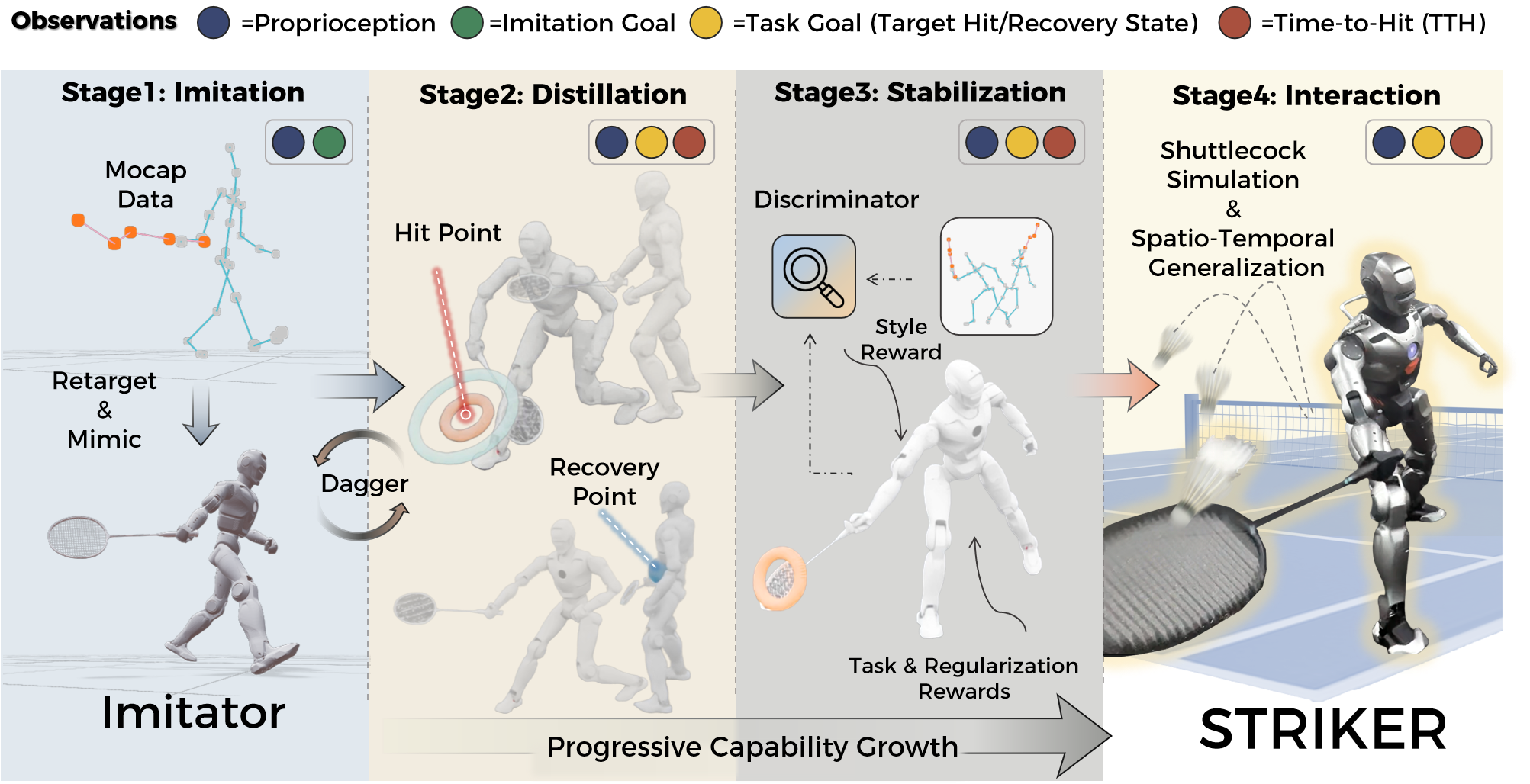

From Human Demonstrations to Robotic Execution: The Imitation-to-Interaction Framework

The Imitation-to-Interaction Framework utilizes Human Motion Capture (MoCap) data as the initial source of knowledge for robotic task learning. This approach involves recording the movements of a human expert performing a desired task using MoCap systems, which track the positions and orientations of markers placed on the human body. The resulting data provides a detailed kinematic representation of the expert’s motion, serving as a demonstration for the robot to learn from. By leveraging these expert demonstrations, the framework bypasses the need for manual programming of complex movements and enables the robot to acquire a foundational understanding of the task before further refinement through interaction and learning algorithms.

Motion retargeting is the process of transferring kinematic data captured from a human performer to a robot with potentially different proportions and joint configurations. This adaptation involves scaling, re-orientation, and re-mapping of joint angles to ensure the robot can physically execute the motion, while preserving the intent of the original human demonstration. The resulting adapted motion data then defines the behavior of a ‘Teacher Policy’, which serves as a reference for learning and knowledge transfer. This policy dictates the robot’s actions based on the retargeted human motion, providing a clear example of the desired task execution before being refined through distillation techniques.

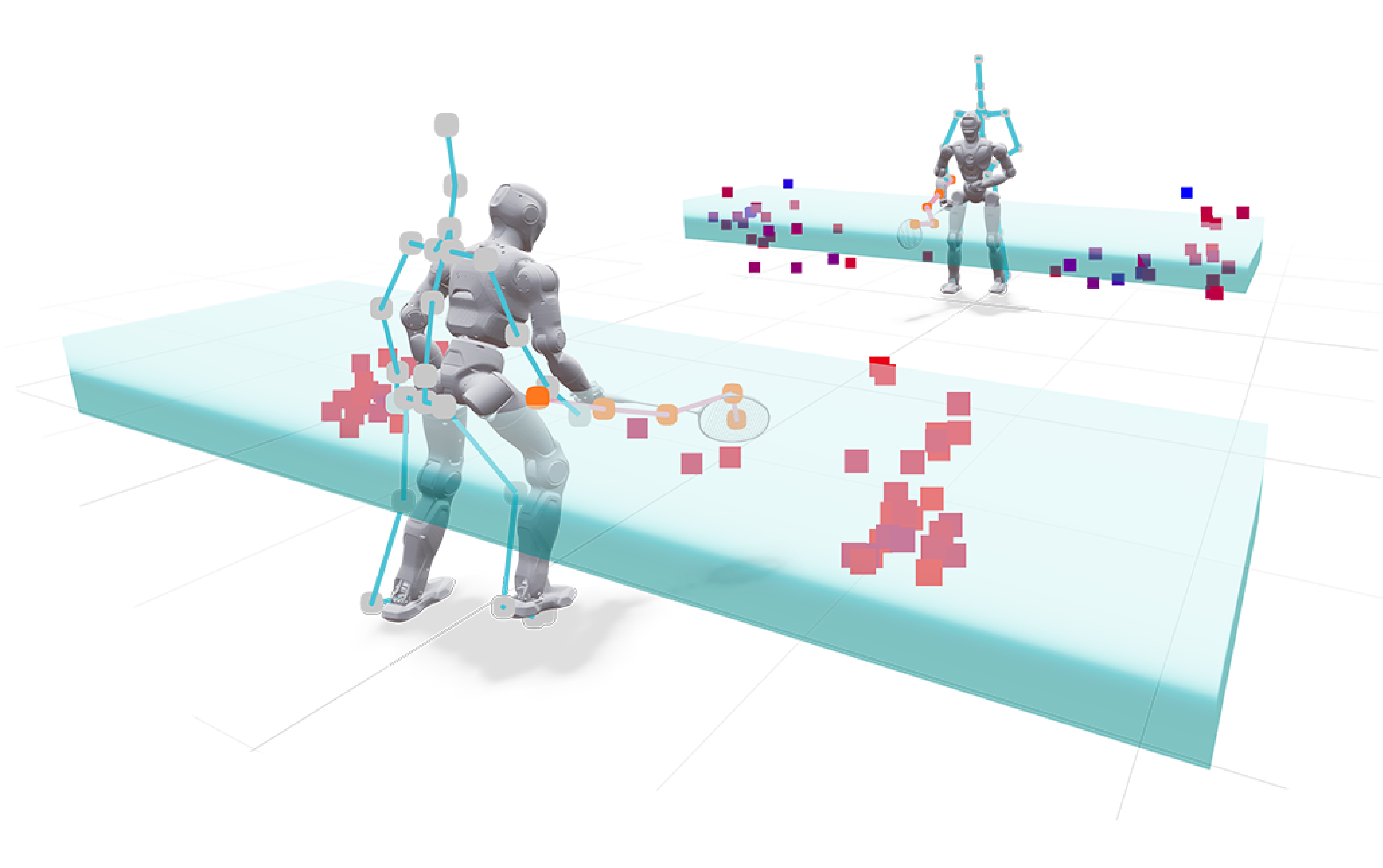

Goal-Conditioned Distillation facilitates knowledge transfer from the established ‘Teacher Policy’ – derived from human motion capture – to a ‘Student Policy’ capable of autonomous operation. This process involves training the Student Policy to replicate the Teacher Policy’s actions, but conditioned on specific goals. Performance is evaluated and optimized using quantitative metrics, primarily ‘Time-to-Hit (TTH)’ – measuring the efficiency of reaching a target – and verification of the ‘Target Hit State’, ensuring the desired outcome is achieved. The distillation process effectively compresses the knowledge from the high-dimensional Teacher Policy into a more streamlined Student Policy, enabling efficient and goal-oriented robot control.

Trial and Error: Reinforcement Learning and Dynamic Adaptation

The student policy undergoes iterative refinement through Reinforcement Learning (RL) implemented within a physics simulation. This approach enables the agent to learn optimal control strategies via trial and error, receiving rewards or penalties based on its performance in simulated scenarios. The physics simulation provides a controlled environment for the agent to explore different actions and observe their consequences without the risks associated with real-world experimentation. Through repeated interaction with the simulation, the RL algorithm adjusts the policy’s parameters to maximize cumulative rewards, effectively learning a control strategy tailored to the simulated task.

Domain randomization is implemented to enhance the policy’s generalization capability and robustness to unforeseen variations in real-world deployment. This involves systematically altering simulation parameters during training, including variations in object masses, friction coefficients, gravity, and visual textures. By exposing the reinforcement learning agent to a wide distribution of these randomized conditions, the resulting policy learns to be less sensitive to specific simulation settings and more adaptable to the uncertainties present in the physical environment. This approach effectively bridges the reality gap, allowing for improved performance when the trained policy is transferred to a real-world robotic system.

Adversarial Motion Priors (AMP) are implemented to improve both the stability and realism of the learned robotic motions. This technique utilizes a discriminator network trained to distinguish between motions generated by the reinforcement learning policy and a dataset of natural human-like movements. The policy is then penalized during training based on the discriminator’s ability to identify its generated motions as artificial, effectively encouraging the robot to adopt more plausible and fluid movements. This adversarial process provides a supplementary reward signal that complements the primary reinforcement learning objective, leading to enhanced learning stability and demonstrably more natural-looking robotic behavior.

The Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) serves as a state estimator within the physics simulation, providing continuous estimates of the shuttlecock’s position, velocity, and orientation. This is achieved through a recursive algorithm that integrates predictions based on the system’s dynamic model with measurements obtained from simulated sensors. The EKF incorporates process noise to account for model inaccuracies and measurement noise to handle sensor limitations, producing a minimum variance estimate of the shuttlecock’s state. Accurate state estimation is critical for precise control, enabling the reinforcement learning agent to effectively predict the shuttlecock’s trajectory and plan appropriate actions for interception and manipulation.

The Illusion of Competence: Achieving Robust and Adaptive Badminton Play

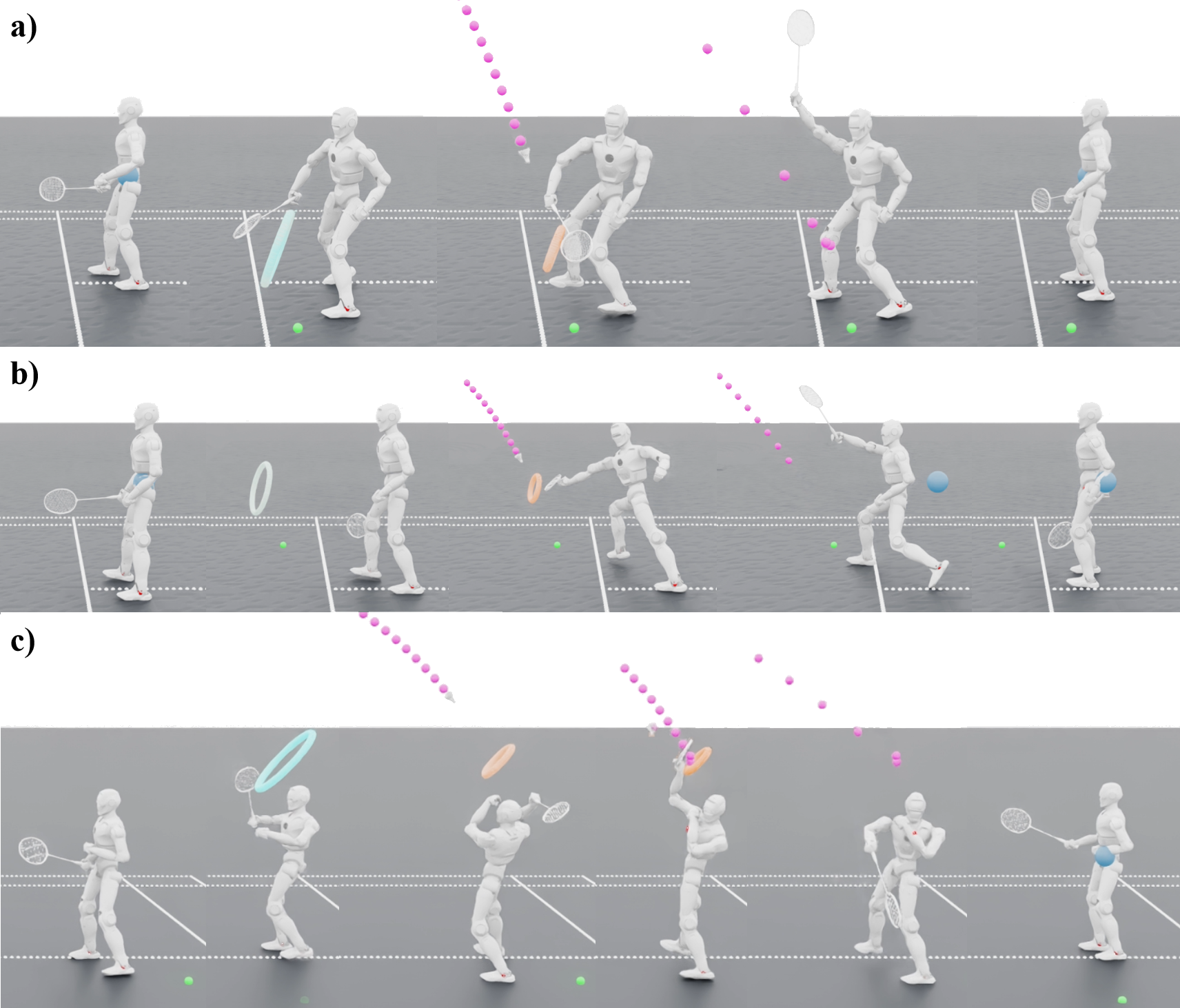

The robotic framework successfully executes the complex motor skill of a badminton lift, highlighting a significant advancement in embodied artificial intelligence. This feat isn’t simply about striking the shuttlecock; it demands precise, coordinated movement across the robot’s entire body – a demonstration of sophisticated ‘Whole-Body Coordination’. The system integrates visual perception with dynamic motion planning, allowing for accurate tracking of the shuttlecock and timely adjustments to the robot’s posture. Crucially, the framework doesn’t rely on pre-programmed trajectories, but instead learns to adapt its movements in real-time, resulting in effective impacts that mimic the power and precision of a human player. This capability represents a key step towards robots that can participate in dynamic, interactive sports and other physically demanding tasks, though let’s not pretend it’s actually playing badminton.

The robotic badminton player exhibits a remarkable capacity to maintain consistent performance even when faced with unpredictable real-world scenarios. This robustness isn’t achieved through meticulous pre-programming, but rather through a training regimen combining domain randomization and adversarial training. Domain randomization involves exposing the robot’s simulated learning environment to a wide range of variations – differing shuttlecock trajectories, slight adjustments to its starting pose, and even simulated disturbances – forcing it to generalize its control strategies. Complementing this, adversarial training introduces subtle, deliberately disruptive forces during simulation, prompting the robot to actively learn how to counteract these perturbations and maintain stability. The synergistic effect of these two techniques equips the system with an inherent adaptability, enabling it to consistently execute lifts despite imperfect initial conditions or unexpected external forces encountered during physical deployment. It’s still just a robot, though, reacting to stimuli – hardly strategic play.

A critical aspect of consistent badminton performance lies in the ability to regain balance and readiness after each shot; this robotic system demonstrates a reliable capacity to achieve what is defined as a ‘Target Recovery State’. Following the execution of a lift – whether forehand or backhand – the robot consistently returns to a stable posture, effectively resetting its center of gravity and aligning its body for the next movement. This isn’t simply a return to any stable pose, but a specific, pre-defined configuration optimized for swift transitions into subsequent actions, such as preparing for a defensive shot or anticipating the opponent’s return. The consistent achievement of this ‘Target Recovery State’ highlights the effectiveness of the robot’s control algorithms and physical design, enabling it to maintain a dynamic yet stable presence on the court and perform a sequence of complex movements with minimal disruption.

The culmination of this research is demonstrated through the robot’s impressive performance on physical hardware, achieving a 90% success rate in executing forehand lifts and a 70% success rate for more technically demanding backhand lifts. This substantial level of accuracy signifies a robust transfer from simulated training environments to real-world application – a critical hurdle in robotics. The consistently successful execution of these complex badminton strokes validates the effectiveness of the developed framework and highlights the robot’s capacity to adapt to the unpredictable dynamics of a physical sport, paving the way for more versatile and adaptable robotic systems. But let’s be honest, it’s still a long way from beating a seasoned player. The game isn’t about perfect execution; it’s about reading your opponent, anticipating their moves, and exploiting their weaknesses – something a robot, for all its cleverness, still can’t do.

The pursuit of elegant robotic motion often collides with the messy reality of physical execution. This work, detailing a progressive reinforcement learning approach to badminton for humanoids, feels less like a breakthrough and more like a carefully managed accommodation. The zero-shot transfer from simulation is impressive, certainly, but one anticipates the inevitable edge cases, the subtly warped court surfaces, the unexpected gusts of air. As John McCarthy observed, “Every program has at least one bug.” This isn’t a criticism; it’s the nature of the beast. The robot may learn to play badminton, but the system will always require tending, a constant negotiation between idealized models and the unpredictable world. The ‘Adversarial Motion Priors’ are a clever patch, delaying the inevitable, perhaps, but rarely eliminating it.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstration of zero-shot transfer is, predictably, touted as a breakthrough. The history of robotics is littered with ‘breakthroughs’ that required bespoke hardware, precisely calibrated environments, and a team of PhDs coaxing the system through each attempt. This work is unlikely to fundamentally alter that trajectory. The implicit assumption – that a simulation, no matter how detailed, can fully encapsulate the chaotic reality of a shuttlecock’s flight and the nuanced physics of impact – remains questionable. One anticipates the inevitable divergence between simulated performance and real-world robustness.

Future efforts will undoubtedly focus on ‘domain randomization’ – essentially, throwing more chaos at the simulation in the hope that something sticks. A more fruitful avenue may lie in accepting that perfect simulation is an asymptotic goal. Perhaps a hybrid approach, combining learned policies with reactive, low-level control, could yield more consistent results. The robot, after all, already ‘knows’ that things fall down. Forcing it to relearn this through millions of simulated iterations feels… inefficient.

Ultimately, the true test won’t be the elegance of the learning algorithm, but the cost of deployment. A robot that can play badminton in a lab is a curiosity. One that can consistently return a serve amidst the unpredictable conditions of a real match – and doesn’t require a dedicated technician hovering nearby – is a different proposition entirely. The devil, as always, resides in the details – and the maintenance schedule.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.08370.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

2026-02-10 16:33