As I delve deeper into Robert Towne’s fascinating life story, I can’t help but be in awe of this remarkable man and his incredible journey in the world of Hollywood. Born into a humble background in San Pedro, California, Towne’s early years were filled with determination and a relentless pursuit of knowledge and creativity.

Robert Towne, the renowned screenwriter behind “Chinatown” and an Academy Award winner, passed away on Monday at his residence in Los Angeles. He was 89 years old.

His publicist Carri McClure announced the news on Tuesday.

In the late 1950s, Towne began his screenwriting journey by working with budget filmmaker Roger Corman. His talent quickly became recognized in Hollywood, leading him to be hired as a “script doctor” for struggling movie projects like “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967) and “The Godfather” (1972), where he made uncredited improvements.

During the time of the New Hollywood filmmaking, Townes wasn’t already a legendary figure when he came across a 1969 photo feature in West, the former Sunday supplement of the Los Angeles Times.

In this piece, titled “Raymond Chandler’s L.A.,” the photographer captures contemporary images of Los Angeles sites, making it seem as if it were still the era of Chandler’s gritty private eye, Philip Marlowe, from the late 1930s and ’40s. A striking photograph showcases a classic convertible parked next to an antique streetlight near Bullocks Wilshire, the renowned Art Deco department store on Wilshire Boulevard.

Towne, a native Los Angelesan who grew up during the Depression, expressed astonishment in a 2008 Writers Guild Foundation interview about how one could revive the L.A. of his vague memories through thoughtful choices of locations scattered around the city, several of which he was familiar with.

“That got me started thinking.”

To put it another way, Townes frequently admitted that creating the photo essay served as the inspiration for penning his most renowned and praised screenplay, “Chinatown.”

In the world of cinematic masterpieces, I’d like to share my perspective on “Chinatown,” a 1974 film directed by Roman Polanski. I was there, front and center, as Jack Nicholson brought private investigator J.J. “Jake” Gittes to life on the silver screen. Faye Dunaway joined him in this intriguing journey set against the backdrop of 1937 Los Angeles.

In 1973, Townes’ contribution to the making of “The Godfather” was publicly recognized in a unique way when director Francis Ford Coppola won an Oscar for screenwriting. During his acceptance speech, he paid homage to Townes by acknowledging that he wrote the poignant scene between Marlon Brando and Al Pacino in the garden. This scene symbolizes the passing of power from the elder Mafia boss to his son Michael, and subtly conveys the deep-rooted affection between them. Townes penned this powerful scene only a night before it was filmed.

Two years later, the press was calling Towne “the hottest writer in Hollywood.”

As a passionate cinephile and screenwriter, I’ve had the privilege of immersing myself in the world of film for many years. One particular topic that has always intrigued me is the artistry behind iconic movie scripts. The career of Robert Towne, an esteemed American screenwriter, stands out as a remarkable example of excellence and versatility.

Among Towne’s other screenwriting credits are “The Yakuza” (with Paul Schrader), “The Two Jakes” (a “Chinatown” sequel), “Days of Thunder,” “The Firm” (with David Rabe and David Rayfiel), “Mission: Impossible” (with David Koepp) and “Mission Impossible: II.” As a frequent script doctor, Towne also did uncredited work on films such as “Drive, He Said,” “The Parallax View,” “Marathon Man,” “The Missouri Breaks” and “Heaven Can Wait.”

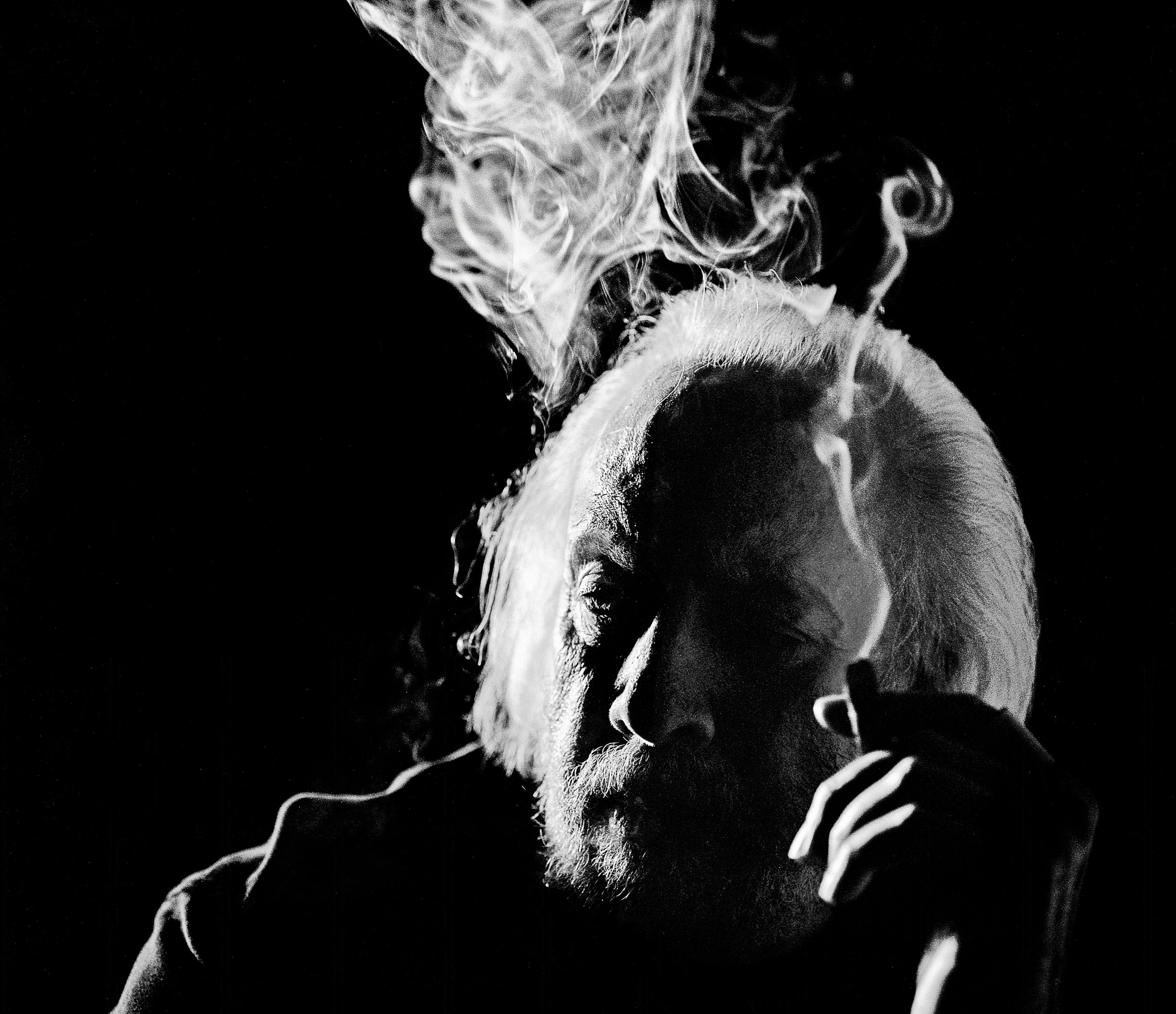

A screenwriter, tall with a beard and having a soft-spoken voice, who preferred thin cigars, made his directorial debut with the 1982 film “Personal Best,” based on his own script about two female track athletes. Later, he wrote and directed films such as “Tequila Sunrise,” “Without Limits” (in collaboration with Kenny Moore), and “Ask the Dust,” which is set in Depression-era Los Angeles.

Towne was involved in both writing and directing plans for the 1984 film “Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes,” which is an adaptation of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novel “Tarzan of the Apes.” However, after being dissatisfied with the final product, co-written by Michael Austin and directed by Hugh Hudson, Towne requested that his name be changed in the credits to P.H. Vazak – a pseudonym he used, which happened to be the name of his Komondor, a Hungarian breed known for guarding livestock. Consequently, Vazak and Austin shared an Oscar nomination.

As a movie enthusiast, I’ve come across Towne’s screenplays, but none of them have managed to leave an enduring mark like “Chinatown.” This film continues to captivate writers and film students, making it one of the greatest scripts ever penned in my opinion. In fact, according to a poll conducted by the Writers Guild of America in 2006, “Chinatown” ranked as the third best screenplay, trailing only behind “Casablanca” and “The Godfather.”

At the American Film Institute’s graduation event in 2014, Coppola awarded Towne an honorary doctorate in fine arts. She praised his “Chinatown” script, stating that it served as the essential model for emerging screenwriters, embodying the perfect blend of structure and style, widely studied as a blueprint across the globe.

In the 2020 publication “The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood,” Sam Wasson disclosed that a prominent screenwriter in Hollywood had accepted assistance from an unacknowledged collaborator for over four decades. Namely, Towne frequently sought the expertise of Edward Taylor, a long-standing friend, when working on his scripts, such as “Chinatown.”

In the mid-1960s, Taylor, a literature and theater enthusiast, and Towne’s roommate at Pomona College, began covertly collaborating on Towne’s scripts. According to the book, Taylor was content with staying hidden from the limelight. Despite this secrecy, Towne sought Taylor’s input up until Taylor’s passing in 2013 – a collaboration that took place through meetings or phone conversations.

In a 1983 essay for a special edition of the “Chinatown” screenplay, Towne, who wasn’t interviewed for the book, made a subtle recognition of his secret collaborator in more straightforward terms: During the autumn of 1972 on Catalina Island, while crafting the core of the script, Towne was frequently visited by his longtime friend Taylor. He described Taylor as serving variously as his conscience (Jiminy Cricket), brilliant advisor (Mycroft Holmes), and literary mentor (Edmund Wilson) since their college days.

Robert Burton Schwartz, later known as Mr. Towne, was born on November 23, 1934, in Los Angeles. When he was just two years old, his family relocated to San Pedro. There, his father opened a women’s apparel store named Towne Smart Shop, which soon led to him being referred to as Mr. Towne.

In the Writers Guild Foundation interview, Towne expressed his belief that his father, who went on to be a prosperous real estate developer, took a liking to something at that time. Before the birth of Towne’s brother Roger, their father had already made the decision to legally change his name. (Roger Towne later collaborated on the screenplay for the 1984 movie “The Natural.”)

The family later moved to Rolling Hills on the Palos Verdes Peninsula and then to Brentwood.

In the 1950s at Pomona College, Claremont, Towne delved into philosophy. Additionally, he joined a creative writing course where one of his short stories, inspired by his recent experience working on a commercial tuna-fishing vessel, captivated everyone’s interest, as he reminisced.

During his college years, Towne pondered the idea of pursuing a journalism career. However, by the late 1950s, Towne – having completed military service – found himself in Hollywood attending an acting class led by blacklisted actor Jeff Corey. Notable alumni of this class included James Coburn, Sally Kellerman, and Richard Chamberlain. Among his fellow students was Nicholson, with whom Towne later developed a close friendship.

“I honed my writing skills through seven years of improvisation in that class. I learned what worked dramatically and dialogually, as well as what people could and couldn’t effectively express.” (Towne looked back.)

An early opportunity in his career came when a fellow classmate, Corman who was a swift filmmaker and director, looking to enhance his understanding of acting, proposed that he try his hand at scriptwriting. “Making ends meet through writing for Roger was challenging,” Towne shared, “but he provided me with the initial push.”

In 1960, Towne made his debut as a screenwriter for Corman’s “Last Woman on Earth,” a science fiction film where Towne acted under the name Edward Wain in one of the leading roles. Using the same stage name, Towne appeared in another Corman production, “Creature From the Haunted Sea” (1961). For Corman, Towne penned down the screenplay based on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tomb of Ligeia” (1964), featuring Vincent Price in the lead role.

As a passionate film enthusiast looking back on Towne’s illustrious career, I can’t help but mention his significant contributions to the small screen. In the 1960s, when the world of television was just beginning to blossom, Towne penned scripts for some groundbreaking shows. He wrote for “The Man From U.N.C.L.E,” which captivated audiences with its espionage and adventure. I fondly remember “The Outer Limits,” a science fiction anthology series that pushed the boundaries of what was possible on television. Towne’s work on “The Lloyd Bridges Show” and “The Richard Boone Show” added depth to these character-driven dramas. Later in life, he continued his involvement in television as a consulting producer on the wildly popular “Mad Men,” which brought mid-century America to life on our screens.

Towne’s screenwriting journey gained momentum when “Bonnie and Clyde” stars and producers Beatty and Arthur Penn required assistance on the script written by David Newman and Robert Benton. For his valuable input, Towne was acknowledged in the film’s credits as a “creative consultant.”

In his popular book about the New Hollywood era, “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” author Peter Biskind characterizes screenwriter Towne as exceptionally well-read. This stands out in an industry known for its high dropout rate, where reading books is not a common practice.

I’ve always been captivated by how deeply he understood the intricacies of storylines and the subtleties of dialogue in films. He could effortlessly connect these elements to the rich tapestry of Western drama and literature, providing insightful explanations that brought new depth to my appreciation of cinematic art.

In every written page, producer Gerald Ayres shared with Biskind, there was an uncanny talent of the author to instill a subtle sense of dampness, as if they had merely exhaled on it. Reading these pages was never a mere comprehension of the plotline, but an authentic and unplanned experience touching the essence of human existence.

When penning “Chinatown,” a story centered around a complex water and real estate scandal, Townes drew inspiration from the debated past of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This engineering marvel, which transported water from the Owens Valley in the eastern Sierra Nevada to L.A. during the earlier part of the century, provided the foundation for Towne’s intricate plot.

In an interview with The Times in 2004, Towne explained that his approach to making “Chinatown” was not about creating an exotic film filled with Maltese falcons and jeweled birds. Instead, he aimed to bring real-life elements to the crime genre. He wanted to focus on a common crime, like water and power, and present a detective who was different from typical characters, such as Philip Marlowe. This detective would only handle divorce cases due to their financial rewards.

Prior to the start of “Chinatown” production in 1973, Towne and Polanski frequently clashed for several weeks as they worked on trimming down and refining Towne’s extensive screenplay.

Their biggest battle was over the ending.

Townsend urged Evelyn Mulwray (Dunaway), the grieving widow of the slain water and power department chief engineer, to take action against her powerful father, Noah Cross (Huston). As a teenager, he had raped her and was also the father of her young daughter whom she desperately wanted to protect from him.

In 1969, Polanski, whose pregnant wife Sharon Tate was brutally murdered by the Manson family, harbored a chilling plan: He intended for Evelyn to meet a tragic end, leaving her young daughter in the clutches of her malevolent father. (Evil triumphant)

In the end, the director got what he wanted, and the movie takes an unforgettable turn when Evelyn tries to escape with her child in a car through the streets of Chinatown.

“The movie ‘Chinatown,’ which was widely praised by critics and a financial success, earned eleven nominations at the Academy Awards, among them for best picture, best director, best actor, and best actress.”

In an interview with The Times in 1999, Towne, the film’s sole Oscar laureate, acknowledged Polanski’s perspective on the ending being correct.

In 1997, Towne was honored with the prestigious Screen Laurel Award from the Writers Guild of America. This esteemed accolade is bestowed upon a writer for their remarkable collection of screenplays.

As a film enthusiast, I’d put it this way: I’ve been fortunate enough to be a father twice over. My first daughter, Katharine, was born to my former spouse, Julie Payne, who is the offspring of esteemed actors John Payne and Anne Shirley. Our marriage unfortunately didn’t last. In the second chapter of my life, I met Luisa Gaule and welcomed another precious daughter, Chiara, into our family.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Clash of Clans January 2026: List of Weekly Events, Challenges, and Rewards

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

2024-07-18 18:29