As a lifelong admirer of Samuel Beckett and his profound works, I found “Dance First” to be a compelling exploration of the man behind the myth. John Byrne’s portrayal of Beckett was nuanced and moving, capturing both the weary melancholy and incongruous longing that seemed to define the author.

Samuel Beckett’s work, a legendary Irish writer who moved to Paris and flourished in the French language, stands as a stark contrast to the narrative style of biopics. Biopics, with their tendency towards uplifting clichés and sentimental depth, are foreign to the minimalist, anti-establishment ethos that Beckett embodied throughout his groundbreaking literary career in the latter half of the 20th century.

As a private author myself, I find deep admiration for Samuel Beckett who, despite winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1969, chose to avoid the public eye and the glamour that came with it. His decision to hide away from the celebrity circus in Tunisia speaks volumes about his character and values. It takes a special kind of person to prioritize their work over personal recognition, especially when faced with such an esteemed honor like the Nobel Prize.

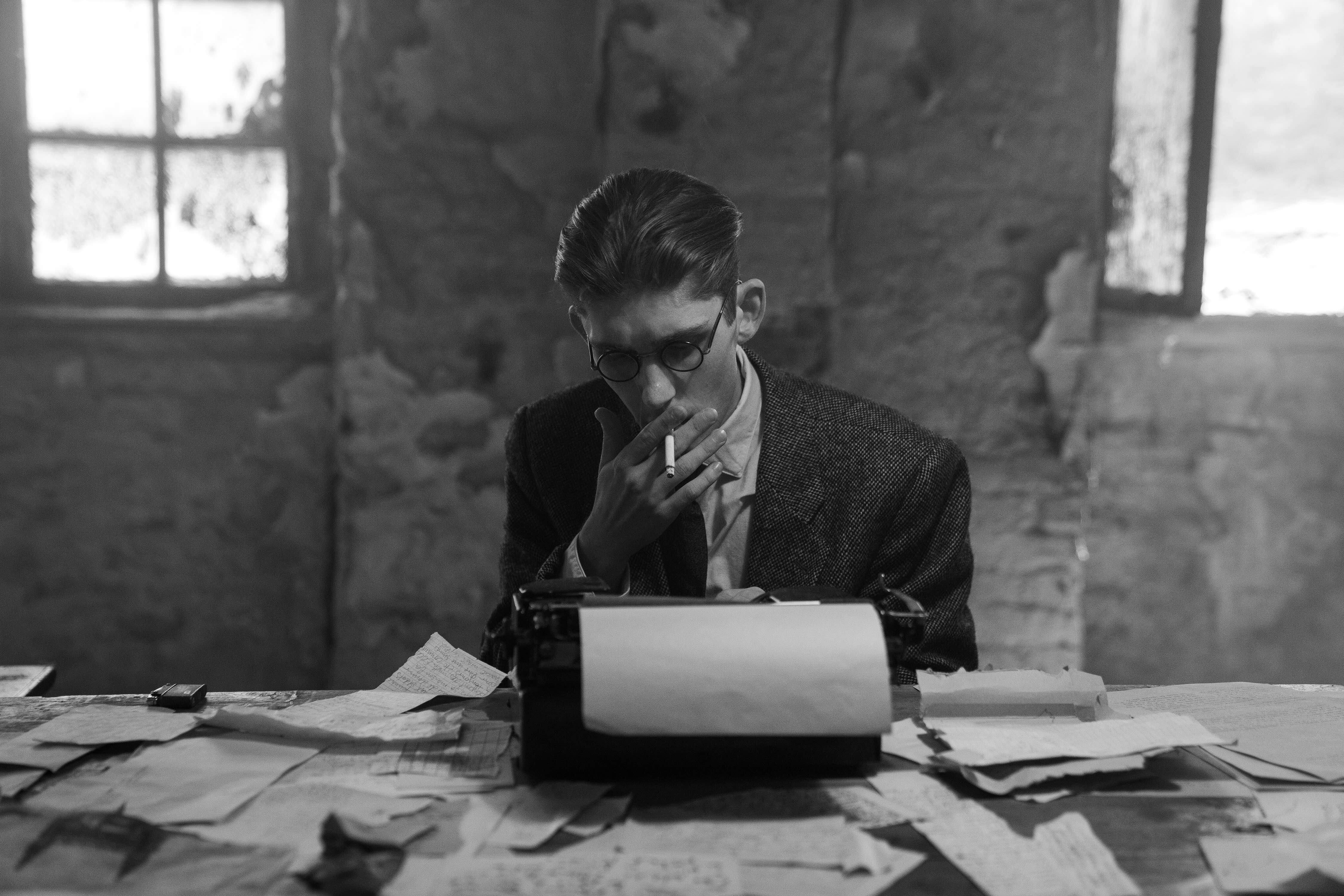

In “Dance First,” a film by James Marsh about the life of Beckett, cinematographer Antonio Paladino uses stark black and white imagery. Despite this classic style, the movie starts in an unconventional manner. The story opens with Beckett (played by Gabriel Byrne), dressed somberly for a funeral, attending the Nobel Prize ceremony in Stockholm. He murmurs to his wife, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil (portrayed by Sandrine Bonnaire), “What a disaster!” as he listens to the accolades bestowed upon him from the podium.

I’ve come across accounts that ascribe the “catastrophe” quote to Beckett’s wife, a woman who, much like her husband, shunned the limelight. However, screenwriter Neil Forsyth daringly deviates from conventional realism in his work, instead embracing an unrestrained, fantastical style.

Instead of maintaining reality or propriety, Beckett suddenly bursts onto the stage, snatches the bill and exits noisily by scaling the side wall to avoid public gaze. He journeys to an ancient setting that could pass for a Greek theater or perhaps one of his own productions, where he engages in a profound dialogue with his other self, reminiscent of a purgatorial experience.

Byrne, acting alongside himself, vividly portrays the dual facets of Beckett’s mind. One Beckett, somber and regretful in formal garb, humbly accepts the award to donate the proceeds. However, his other Beckett, casually skeptical and wearing tweed, provocatively asks, “Who do you feel requires your forgiveness the most?”

The movie is structured around reflective segments focusing on people who had a significant impact on Beckett’s moral compass. This narrative tool, somewhat reminiscent of a conventional stage play, offers a straightforward and dramatic means to present different chapters of his life in an organized manner.

As I sat down to watch “Dance First,” the title brought to mind Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” and its famous line that puts dancing above contemplation. However, this film shares only a fleeting resemblance with Beckett’s absurdist style. In my perspective, as a movie critic, it carves out its unique identity, offering a fresh take on the dance genre.

Beckett consistently redefined each artistic medium he explored with a relentless focus on minimalism. In works like “Waiting for Godot,” “Endgame,” the trilogy “Molloy,” “Malone Dies,” and “The Unnamable,” novels, and even his 1965 screenplay “Film,” he stripped away all unnecessary elements, defying conventional norms to reveal what can be expressed when everything extraneous has been removed.

Meaning isn’t imported into Beckett’s work but enacted through a perfect alignment of style and content. By contrast, Forsyth’s screenplay for “Dance First” serves as a container for biographical reportage and interpretation. There’s a journalistic quality to the movie, which delivers a readily digestible summary of Beckett’s life, with all the important moments neatly enumerated.

As a devoted fan, I found the film captivating due to its compassionate portrayal of striving to understand the man behind the myth. Unlike some popular perceptions of Samuel Beckett, Sam Byrne’s portrayal presents a more tender and vulnerable side. Despite exuding a weariness tinged with melancholy, there was an unexpected yearning for confession that resonated deeply. With unwavering honesty, he depicted the elderly Beckett as someone dragging his weary body towards the end, but not without a hint of dark humor and recurring metaphors that reflect Beckett’s writing style. The depiction of mortal decline was spot-on, serving as a testament to the physical struggles and philosophical musings that are integral to Beckett’s work.

However, despite adhering to a factual timeline, the film carries an air of fictionalization, as it transforms Samuel Beckett’s journey into brief, standalone episodes, which inevitably leads to some distortion and exaggeration in the process.

Samuel Beckett, the renowned author, was characterized by a strained connection with his critical and dissatisfied Protestant mother, May (portrayed by Lisa Dwyer Hogg), who served as an initial source of guilt for him. The budding Beckett, skillfully portrayed by Fionn O’Shea, sought escape from Ireland in part to free himself from her firm grasp, but the movie does not delve into other aspects of a relationship that would persistently influence Beckett’s work during his entire career.

The portion covering Lucia Joyce (famously known as Gráinne Good, James Joyce’s daughter who held a misguided belief about marrying Beckett), as well as scenes portraying Beckett’s wartime Resistance activities, appears to be compressed in a manner that seems questionable. However, the performers manage to deliver moments that surpass simple recapitulation.

The dynamic between Aidan Gillen’s portrayal of James Joyce and O’Shea’s Beckett is intricately portrayed. While initially reluctant to take on the role, Joyce is eventually swayed by Beckett’s admiration and dedication. Interestingly, Joyce perceives in Beckett not just a genius but also a potential suitor for his troubled daughter. This realization sparks a plan that prompts Gillen’s character’s practical wife, Nora (played by Bronagh Gallagher), to take decisive action. Unlike her husband, who is subtly manipulative, Nora employs more direct tactics in her maneuverings.

Samuel Beckett’s detachment, his knack for resisting being ensnared by others’ demands, propels him towards becoming a Great Writer, yet this trait becomes increasingly evident as the narrative unfolds, focusing on Suzanne (portrayed by Bonnaire, in her mature role, and Léonie Lojkine, as Beckett’s girlfriend). Both actresses skillfully portray not only Beckett’s character’s dignity but also his keen insight, strategic wisdom, and prudent reserve.

As a movie reviewer, I’d put it this way: In the film, Suzanne embodies the role of Beckett’s steadfast companion, shielding him from distractions that might impede his lofty artistic pursuits. It’s debatable whether Beckett would have blossomed as he did without the anchor she provided. Loyal in his unique way, Beckett remained devoted to the woman who stayed by his side during his harrowing recovery from a near-fatal street attack in 1938. Throughout their perilous war years, Suzanne stood by him, offering love and courage as they both served with the Resistance.

1. When Barbara Bray (Maxine Peake), who is BBC’s script editor and eventually becomes Beckett’s long-term partner, appears in the narrative, Suzanne navigates the tricky marital complexities with caution. The suffering that Beckett causes for both women is reflected subtly on his rugged face. Although he may be self-centered, it’s crucial not to underestimate his capacity for compassion.

As a movie enthusiast, I find that words often fall short when it comes to capturing the depth of pain something like Beckett’s “Play” brings about. In this audacious one-act, he masterfully transforms the complex tale of infidelity into an artistic entity. The characters – a husband, wife, and mistress – are stuck in eternal urns within an undefined afterlife, reenacting their story at breakneck speed. Despite the language’s limitations, Beckett succeeds in encapsulating the weight of suffering and human emotions in this extraordinary play.

While Beckett is often associated with despair, he was also passionate about sports such as rugby, cricket, and tennis, appreciated beauty in women, valued male camaraderie, and enjoyed fine whiskey. O’Shea can accommodate this less melancholic aspect of Beckett, but Byrne’s portrayal leans towards a more reclusive character who might be more comfortable in a monastery or scholarly setting.

Despite not being overly dramatic or sentimental, the deep emotional sensitivity of a writer who felt intensely is clearly evident. “Dance First” might not be typically Beckett-like, but it brings to life a character who, destined for literary greatness, never questioned his humanity – fully human in all its complexity.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- FC Mobile 26: EA opens voting for its official Team of the Year (TOTY)

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

2024-08-10 01:01