As I delve into the captivating tale of Phil Lesh, a man who danced with death and emerged victorious, I can’t help but be awestruck by his indomitable spirit. His journey, marked by addiction, health crises, and the loss of a bandmate, is not just a story of a musician, but a testament to human resilience.

Phil Lesh, a key bassist in the Grateful Dead band who contributed significantly to their most adventurous musical journeys while also penning and crooning one of their sweetest tunes, “Box of Rain,” has passed away at the age of 84.

On Friday, an update on Phil Lesh’s Instagram shared the following: “Phil Lesh, the bassist and founding member of The Grateful Dead, passed away peacefully this morning. His family was with him, and he was filled with love. Phil brought immense joy to those around him and leaves behind a rich musical and loving legacy. At this time, we ask that you respect the privacy of the Lesh family.” No cause of death has been disclosed at present.

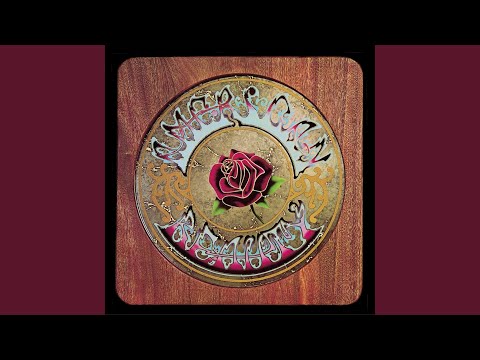

A musician with a classical background and a love for jazz and avant-garde music, Lesh stood out in the Grateful Dead, a band whose main vocalists, Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, were more rooted in folk, bluegrass, and blues. When he joined the emerging Dead in 1964, Lesh was relatively new to rock ‘n’ roll, but he significantly influenced the band’s psychedelic style, particularly during its early phase when members spent part of their time exploring the creative potential of the recording studio. Although Lesh remained adventurous in his pursuits, he also refined his songwriting abilities as the group returned to its folk roots on its influential albums from the early 1970s, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty.” “Box of Rain,” a track dedicated to Lesh’s deceased father and marking his debut lead vocal on a Grateful Dead record, was a highlight of this era, but he also contributed to the writing of “Truckin’,” “Cumberland Blues,” “St. Stephen,” and “New Potato Caboose,” all essential pieces in the Dead’s song catalog.

×

× David Browne, author of a book about the Grateful Dead, described Lesh as someone who had a friendly demeanor but was actually demanding and meticulous. During their initial decade of fame, these traits were evident in the studio – he crafted substantial parts of the auditory mosaics on their second album, “Anthem of the Sun” – and on stage, where he was a vocal proponent for their Wall of Sound, an advanced concert PA system that significantly influenced arena rock. This innovation also pushed the band to take a prolonged break from touring in 1975. Later, Lesh stated that the Grateful Dead were incredibly successful for him until they stopped touring [in 1975]. When they resumed, it was never quite the same. Despite playing excellent music, something seemed amiss.

During the late 1980s and early ’90s, when The Dead experienced an unforeseen surge in popularity, largely due to their only Top 40 hit “Touch of Grey,” Phil Lesh remained with them. However, he became less prominent in their later years, contributing neither songs nor vocals on their last two studio albums. After the band disbanded following Garcia’s death in 1995, a year after they were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Phil Lesh maintained the group’s innovative essence through various musical ventures. These included solo projects like Phil Lesh and Friends as well as collaborations with his former bandmates in groups such as The Other Ones, Furthur, and the Dead. Throughout these endeavors, he aimed to stay faithful to the band’s original guiding principle: “The key aspect of The Grateful Dead doing what they did, and what we’re still trying to do, is the Group Mind. When no one’s really there, there’s only the music. It’s not as if we’re playing the music … the music is playing us.

Philip Chapman Lesh was born on March 15, 1940, in Berkeley, California. Growing up in the Bay Area with working parents, he spent considerable time with his grandmother. The melodies from the New York Philharmonic that filtered into his grandmother’s room ignited a passion for music within him. Encouraged by this newfound love, Lesh convinced his parents to allow him to learn the violin. However, he eventually gave up the violin during his teenage years. His fascination with music led him to pick up the trumpet instead. This interest became so profound that his parents relocated the family back to Berkeley, enabling Lesh to take advantage of the city’s renowned high school music program.

Raised in Berkeley during the height of the Beat Generation, Lesh frequented cultural hubs like City Lights bookstore and Co-Existence Bagel Shop. College life presented some challenges initially; he left San Francisco State halfway through his first term and returned home to attend College of San Mateo before transferring to UC Berkeley. His fascination with the Beat Movement intensified, mirrored by a shared love for avant-garde music with friend Tom Constanten. In college, Lesh was captivated by Thomas Wolfe’s literature, but his passion eventually led him back to music. The innovative compositions of Stravinsky and the freeform explorations of John Coltrane piqued his interest, while he found even greater inspiration in Charles Ives’ work, describing it as “the sound of the world… like the thoughts swirling inside your head when you’re daydreaming.

At non-profit radio station KPFA, Lesh served as a recording engineer, also attending folk music venues which brought him close to Garcia, a skilled bluegrass guitarist. After hearing Garcia perform “Matty Groves” at a gathering in 1962, their friendship quickly formed, with Lesh later recording a tape of Garcia that was broadcast on KPFA. It wasn’t until much later that they decided to work together. In the summer of 1962, Lesh left UC Berkeley for Las Vegas, living with Constanten’s family until they grew tired of his bohemian lifestyle. Returning to Palo Alto by Greyhound bus, Lesh spent a few years sharing a home with Constanten and working at the post office while composing classical music. In early 1965, he attended a Warlocks concert – the band formed by Garcia along with guitarist Bob Weir, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and keyboardist Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. Despite Lesh’s lack of bass-playing skills and his recent interest in rock ‘n’ roll, Garcia invited him to join the Warlocks as their bassist.

As Lesh honed his bass-playing skills with the band initially known as the Warlocks, he established an adaptable, melodic style that eventually became just as iconic for the Dead as Garcia’s intricate guitar solos. When Lesh stumbled upon another group called the Warlocks, he gathered the band members and key associates at his apartment to brainstorm a new name. This naming process ground to a halt until Garcia pulled “the Grateful Dead” from a dictionary.

Back in 1965, I was part of the audience at one of Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests, where The Grateful Dead first took the stage. Over the following year, we became regulars at these psychedelic gatherings, forming significant connections with influential figures like our manager Rock Scully and Owsley Stanley, a key LSD producer who supported us during our initial phase. Known as “Bear,” he later stepped into the role of our sound engineer, a role that mirrored my own passion for sound engineering, which I shared with Lesh.

By late 1966, The Grateful Dead inked a deal with Warner Bros. Records, which granted the band creative freedom and endless studio hours. Leveraging this liberty, Lesh and Garcia promptly utilized it to record their self-titled debut album in 1967. Subsequently, they made full use of this provision by investing excessive time in studio experimentation for “Anthem of the Sun” – the first release to incorporate Mickey Hart as the band’s second drummer and Constanten, a college friend of Lesh, albeit briefly associated with the group. Similarly, “Aoxomoxoa,” an album they ended up recording twice, was another product of their adaptation to a new 16-track recorder. Struggling with accumulating debts, the band decided to use this 16-track recorder to document live performances at Fillmore West and Avalon, resulting in “Live/Dead,” an album that not only revived their financial status with Warner Bros., but also preserved the spontaneous jam sessions they were known for on stage.

Amidst the anticipation surrounding our anthem “Live or Die,” the Grateful Dead found themselves navigating turbulent waters in the early 1970s. In January of that year, no less than nineteen individuals from our circle were apprehended for drug possession in New Orleans – this incident left a lasting impact on our story when Robert Hunter immortalized it in our song “Truckin'”. As if that wasn’t enough, we would uncover by the year’s end that Lenny Hart, Mickey’s father and a key figure in our management, had misappropriated a significant portion of our earnings.

In the vibrant ’70s, I found myself captivated by the ever-changing dynamics of the Grateful Dead. Despite the constant flux in membership – with Mickey Hart rejoining and Pigpen retiring and eventually passing, his position being filled by Keith Godchaux – and a series of unsuccessful business endeavors like managing their own record label, the band managed to find a semblance of stability. This was particularly evident after the double success of “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty,” which not only propelled them to fame but also defined two distinct paths for the band: on stage, they continued to explore the farthest reaches of their sound, while in the studio, they honed their focus on songwriting.

From the start of the ’70s decade up until “Europe 72,” both avenues (studio albums and live performances) were equally successful for the band, especially among their dedicated fan base known as Deadheads. After the release of “Europe 72,” however, the group’s concerts gained more traction, becoming increasingly popular among their fans. Deadheads exchanged homemade recordings of Grateful Dead concerts, a practice supported by the band, which expanded their fan base throughout the ’70s and ’80s and kept them relevant even after they stopped being an active group. Live recordings like their May 8, 1977 performance at Cornell University were deemed significant enough to be preserved in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2011, demonstrating their widespread appeal beyond just Deadheads.

The prolonged success of the band as a live act eventually put a strain on its members, particularly following the exhausting and costly 1974 tour. During this tour, their music was played through a massive “Wall of Sound,” which consisted of over 600 speakers standing at a height of 40 feet and spanning 70 feet in width. In his memoir “Searching for the Sound,” Lesh stated that these forty performances were the most rewarding live experiences he had with the band, but the costs associated with touring the system became unaffordable. After the tour concluded, the Grateful Dead decided to halt their performances for a while.

While Garcia immersed himself in “The Grateful Dead Movie,” anticipating the October 1974 screenings at Winterland would appease fans yearning for live Dead performances, Lesh found himself in a directionless phase. Following his work with electronic composer Ned Lagin on the 1975 album “Seastones,” he began to wander and overindulge in alcohol. In retrospect, he recalled, “I wasn’t sure if (the band) would ever reunite again. To be honest, that fear of an uncertain future drove me to drink. That uncertainty. I had no other bands. The Grateful Dead was my band. I helped bring it into existence.

Despite the brief duration of his break, the hiatus significantly altered Lesh’s role within the band. Previously known for his high harmonies, Lesh had to stop due to damage to his vocal cords, a problem worsened by his alcoholism. Additionally, he distanced himself from songwriting as he grew increasingly detached from the AOR-style albums produced by Arista, feeling more like a supporting artist rather than a key contributor. In conversations with Dead biographer Browne, Lesh admitted, “I wasn’t deeply invested in those records. I felt like a sideman.

In 1982, Lesh’s fog began to clear when he encountered a waitress named Jill Johnson. Two years later, they tied the knot and went on to bring up two sons. Family life proved fitting for Lesh, leading him to quit drinking and embark on journeys with his boys. Interestingly, Lesh wasn’t alone in the Grateful Dead band in overcoming substance issues. However, by the late 1980s, the entire band experienced a shared enlightenment that mirrored the optimistic and popular “Touch of Grey” single gaining unexpected fame in 1987.

The release of “Touch of Grey” drew a newer, more boisterous crowd to the Grateful Dead, contrasting with the longtime Deadheads who had accompanied the band. As Lesh reminisced, “The impact was significant. It attracted many young individuals who were unfamiliar with the culture and vibe that had developed over two decades. While we were delighted by the renewed interest in the group, it fundamentally changed our circumstances. Due to increased demand for our performances, we were compelled to perform at larger venues. This shift to bigger audiences stripped away the sense of intimacy, and for me, the quality of the experience started declining from that point onwards.

Following Garcia’s death from a heart attack due to his heroin addiction in 1995, which led to the disbandment of the Grateful Dead, Garcia’s bandmate Lesh encountered health issues. In 1998, he underwent a successful liver transplant after battling chronic hepatitis C. Post-recovery, Lesh resumed his musical activities with Phil Lesh and Friends, a group consisting of Bay Area musicians initially formed for benefit concerts. By 1999, he reunited with Bob Weir, Mickey Hart, and later Dead associate Bruce Hornsby in the Other Ones, but his stay in the band was short-lived. He and drummer John Molo departed in 2000 to focus on Phil Lesh and Friends. During this period, Warren Haynes, the Allman Brothers Band guitarist who frequently collaborated with Friends, noted that Lesh, having confronted death, decided to pursue his musical passions without any compromise. This approach led to a band that preserved the Grateful Dead’s improvisational essence while also introducing more structure.

In the 2000s, Phil Lesh and His Group surpassed Ratdog, led by Bob Weir, in terms of popularity. Later on, Lesh’s band released one studio album, titled “There and Back Again” (2002), which included songs co-written by Robert Hunter. However, this was his final collection of original music. In 2003, he rejoined the Grateful Dead, a touring group consisting of all four surviving original members. After a 2004 tour, the Grateful Dead disbanded, leading Lesh to focus on “Searching for the Sound: My Life With the Grateful Dead,” an autobiography published in 2005. He successfully beat prostate cancer in 2006.

Following the receipt of a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys in 2007, The Dead reunited to perform two charity concerts in support of Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008. Post this, Lesh and Weir formed Furthur, a band that delved back into the exploratory improvisations characteristic of The Grateful Dead’s cosmic journeys. Furthur functioned for five years, during which time Lesh along with his family established Terrapin Crossroads in San Rafael – a venue and restaurant. Influenced by Levon Helm’s Midnight Ramble shows in Woodstock, Terrapin Crossroads hosted numerous impromptu jam sessions led primarily by Lesh, who often played alongside his grown sons as the Terrapin Family Band; he also invited different iterations of Phil Lesh and Friends to perform there.

Following the breakup of Furthur, Lesh chose to retire from touring, but he consented to take part in “Fare Thee Well: Honoring 50 Years of the Grateful Dead,” a series of three shows marketed as the final performance by the original four surviving members of the band. Although Weir, Kreutzmann, and Hart continued under the name Dead & Company, Lesh declined to participate. He maintained Terrapin Crossroads as his primary venue for performances until its closure in 2021, making way for various festival appearances with Phil Lesh and Friends. Notably, he joined forces with Jeff Tweedy of Wilco and Nels Cline at the Sacred Rose Festival in 2022 to perform a set under the name Philco.

Lesh is survived by his wife, Jill, sons Grahame and Brian and grandson Levon.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

- ‘SNL’ host Finn Wolfhard has a ‘Stranger Things’ reunion and spoofs ‘Heated Rivalry’

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2024-10-25 23:32