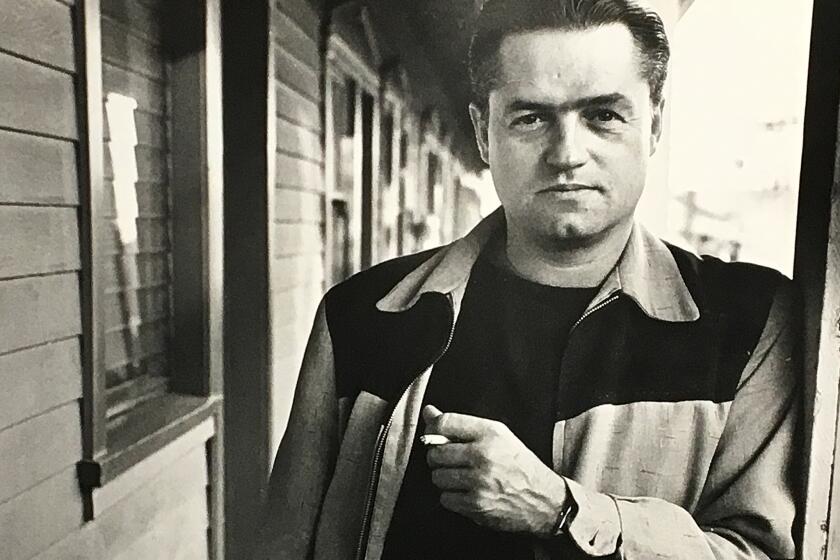

Before he set his sights on Hollywood, Jonathan Demme studied to become a vet.

In “There’s No Going Back,” a somewhat inconsistent biography, film critic David M. Stewart notes that movies might have captivated him since his childhood, yet his passion for animals was equally strong, serving as his parallel fascination, according to the author.

Eventually, chemistry lessons became too challenging, leaving just one subject capturing Demme’s curiosity persistently – the Alligator, the university newspaper at the University of Florida where he could share his film critiques. He opted to forgo a career in veterinary medicine and instead pursued cinema.

Demme, who passed away in 2017, built a notable career by creating films that highlighted perspectives from the constantly evolving fringes of society. He brought attention to women (“Swing Shift”), African Americans (“Beloved”), and HIV-positive gay men (“Philadelphia”) through narratives that showcased their struggles with compassionate storytelling. Among his Hollywood projects, he also produced documentaries such as “The Agronomist,” focusing on Haiti’s sole independent radio station; “Right to Return,” chronicling Hurricane Katrina survivors battling for the right to return home; and “Stop Making Sense.

Demme personally observed the struggles faced by individuals on society’s outskirts as they attempted to access spaces that were predominantly occupied by men, often white, who were unwilling to surrender their claim. His grandmother shared idealized accounts of her role in manufacturing aircraft equipment during World War II, only to be pushed back into her domestic duties. In the Overtown neighborhood of Miami, Demme witnessed how African Americans developed their own distinctive “music and communal spirit” amidst segregation, a culture that he would consistently acknowledge and celebrate in his own films.

Following college, Demme secured a position in public relations at United Artists. By sheer luck, he found himself driving François Truffaut one day. During this ride, the esteemed filmmaker recognized Demme’s potential for directing and encouraged him, despite his initial reluctance. Even after Truffaut signed his copy of “Hitchcock,” Demme maintained that he had no interest in becoming a director. However, Truffaut persistently replied, “Yes, you are.

Despite initial objections, Demme ventured to Hollywood and began working for B-movie producer Roger Corman. His early films included “Angels Hard as They Come,” a 1971 bike movie, and “Black Mama White Mama,” a 1973 prison escape story. Later, he directed “Caged Heat,” a feminist interpretation of the women-in-prison genre that combined satire and progressive politics.

Movies

During the 1970s, Demme directed films that focused on social issues, using both action and comedy to shed light on the struggles of marginalized groups. “Crazy Mama” tells the story of a housewife seeking justice for her slain husband, reflecting Demme’s commitment to acknowledging women’s ongoing battles against a patriarchal society. Meanwhile, “Fighting Mad” (originally titled “Citizens Band,” later renamed “Handle with Care”) tackled themes such as corporate greed, environmental destruction, and the search for human connection in small-town America.

The film “Melvin and Howard” earned two Oscars and was nominated for a third, but Demme’s collaboration with Goldie Hawn on “Swing Shift” turned out to be another disappointing episode in his career. Demme aimed to create a movie portraying a feminist view of women during wartime, while Hawn envisioned it as a lighthearted romantic comedy. Unfortunately, Hawn’s power to veto decisions resulted in a complete overhaul of the ending, effectively stripping Demme’s vision of its political impact. A similar creative clash occurred on the set of “Beloved” about a decade later, where Demme disagreed with Oprah Winfrey regarding the characterization in the supernatural slavery epic. During this time, Winfrey claimed that she was temporarily forbidden from watching daily footage of the filming.

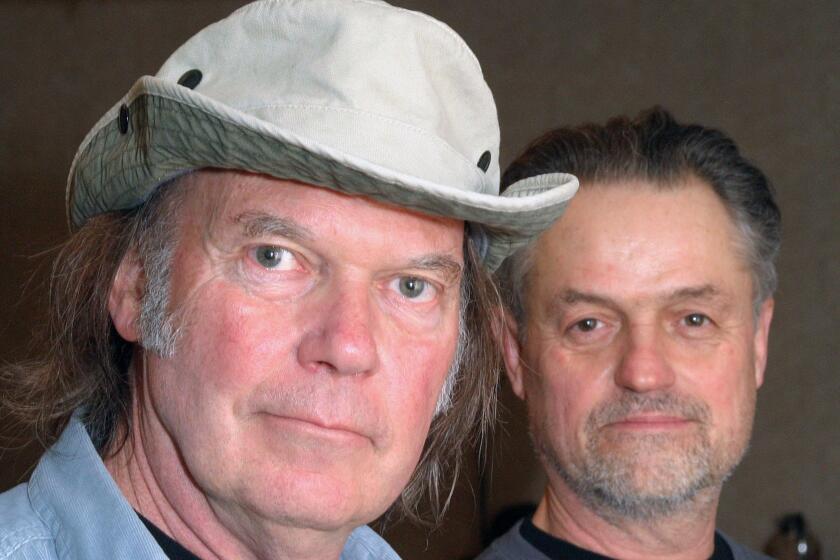

Demme often discovered solace in music, as he frequently mentioned. This refuge manifested through his work such as the Talking Heads concert film “Stop Making Sense” and various Neil Young concert films. Notably, the movie “Something Wild,” made after “Swing Shift,” showcased Jamaican singer Sister Carol and her rendition of “Wild Thing.

Music

It’s no surprise that some of the most influential figures in pop music, such as Neil Young, David Byrne, Bruce Springsteen, and the Pretenders, chose filmmaker Jonathan Demme when they sought to showcase their work on the silver screen.

Despite this, it was his strong affinity towards complex female characters who stood firm amidst a sea of deceitful men that significantly influenced his work, albeit not entirely addressed in Stewart’s succinct analysis. “The Silence of the Lambs,” “Rachel Getting Married,” and “Ricki and the Flash” all portrayed, in equal measure, the resilience and vulnerability of distinct women – confronting the legal system, struggling with addiction, and distancing themselves from their families – who refused to succumb to victimhood.

The title “There’s No Going Back” indicates that this isn’t a full biography of Demme, but rather an exploration of him as a filmmaker. If Stewart’s brief coverage of Demme’s childhood is acceptable (just a few pages), his uneven and sometimes incomplete portrayals of Demme’s films, lacking in overall analysis, are less excusable. The book’s inconsistent methods – such as giving detailed production information for “The Silence of the Lambs” but no film analysis, while providing limited dissection for “Rachel Getting Married” – don’t aid in identifying Demme’s recurring themes as a director. The lack of concluding remarks after Demme’s passing and the end of the book only adds to this issue.

The fact that ‘There’s No Going Back’ has some level of merit lies in the information provided about Demme’s lifelong activism. Beginning with his involvement in the freedom of expression movement, Demme went on to create several documentaries showcasing Haiti’s transition from a dictatorship to a democracy. While political connections may not always be drawn between his dramatized films and this activism, acknowledging how Demme championed voices from places like Haiti and in the wake of Katrina at least brings attention to his lifelong commitment to advocating for society’s marginalized individuals, both on and off screen.

As a young lad, Demme was encouraged by his mother to write about the films he adored so much in order to discover the hidden truths behind their enchantment. However, it seems ironic that the same advice given by Stewart is scarcely applied in “There’s No Going Back.” Despite its good intentions and appreciation, the biography frequently comes across as superficial, struggling to grasp Demme’s body of work and its profound political and cinematic messages. Nonetheless, this book serves as a foundation for future projects that might more skillfully blend life experiences with artistic insights.

Smith is a books and culture writer.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- FC Mobile 26: EA opens voting for its official Team of the Year (TOTY)

2025-07-25 13:32