Author: Denis Avetisyan

Agent-based modeling is emerging as a powerful tool for dissecting the complex interplay of cells and forces that govern tissue development and behavior.

This review explores the Deformable Cell Model, a computational approach for simulating multicellular systems and advancing both fundamental biological insights and bioengineering applications.

Understanding the complex interplay between cellular mechanics and tissue organization remains a fundamental challenge in biology and bioengineering. This is addressed in ‘How high-resolution agent-based models can improve fundamental insights in tissue development and cell culturing methods’, which reviews Deformable Cell Models (DCMs)-a powerful agent-based modeling approach for simulating multicellular systems. By representing individual cells as discrete, physically realistic entities, DCMs offer unprecedented detail in predicting emergent tissue behaviors, from [latex]in\ vitro[/latex] organoid formation to [latex]in\ vivo[/latex] developmental processes. Could these high-resolution simulations unlock new strategies for both fundamental biological discovery and the rational design of improved cell culturing techniques?

Beyond Two Dimensions: The Limitations of Conventional Cell Culture

Conventional cell culture, performed on flat, two-dimensional surfaces, presents a significant departure from the intricate three-dimensional architecture of living tissues. This simplification profoundly impacts cellular behavior, as cells in the body rarely exist in isolation or on a plane; instead, they interact with neighboring cells and a complex extracellular matrix in all directions. Consequently, 2D cultures often fail to accurately mimic physiological conditions, leading to alterations in cell morphology, gene expression, and protein production. These discrepancies introduce substantial limitations in biological studies, potentially yielding results that do not translate to in vivo systems and hindering the development of effective therapies. The absence of crucial 3D cues compromises the predictive power of in vitro experimentation, necessitating the development of more physiologically relevant models to bridge the gap between laboratory findings and clinical outcomes.

The predictive capacity of in vitro experiments and drug screening is significantly compromised by the artificiality of traditional cell culture systems. When cells are grown as a two-dimensional monolayer, they lack the crucial biochemical and biophysical cues present within a living tissue – signals governing cell differentiation, gene expression, and response to therapeutic compounds. Consequently, promising drug candidates often fail in clinical trials despite demonstrating efficacy in vitro, a phenomenon attributable to the discrepancy between simplified lab conditions and the complex reality of the human body. This disconnect stems from the absence of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, nutrient gradients, and mechanical forces that profoundly influence cellular behavior, creating a need for more physiologically relevant models to accurately forecast drug efficacy and minimize costly failures later in development.

The pursuit of biologically relevant insights necessitates a shift away from conventional two-dimensional cell culture systems. These simplified models often fail to accurately mimic the intricate three-dimensional architecture and complex cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions present within living tissues. Consequently, researchers are actively developing more sophisticated in vitro platforms – including spheroids, organoids, and microfluidic devices – to better recapitulate the physiological microenvironment. These advanced models allow for a more nuanced understanding of cellular behavior, improving the predictive power of drug screening and disease modeling. By moving beyond simplistic systems, scientists aim to bridge the gap between in vitro findings and in vivo responses, ultimately accelerating the translation of research into effective therapies and personalized medicine.

Decoding Cellular Mechanics: A High-Fidelity Computational Approach

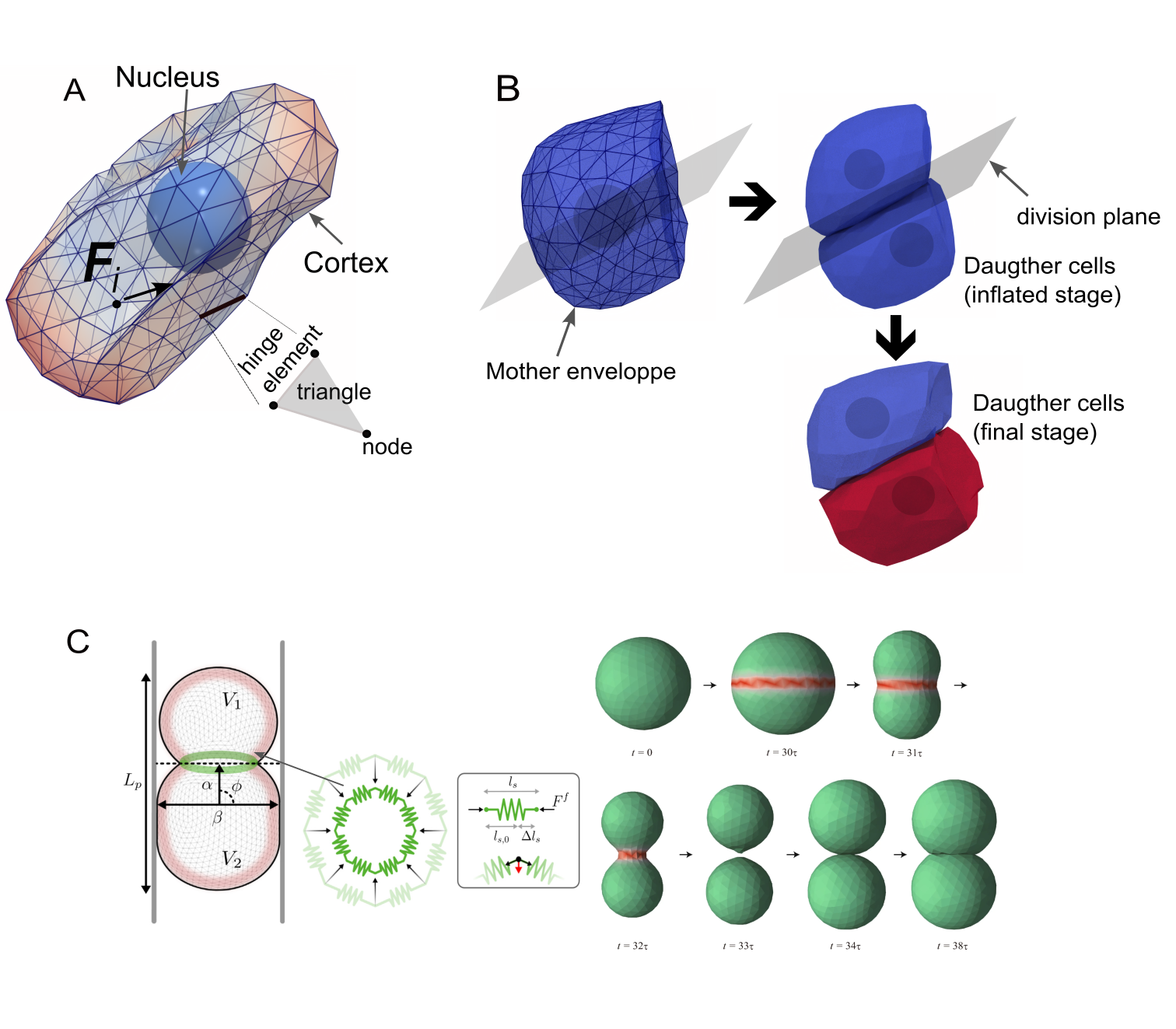

Deformable Cell Models (DCMs) utilize computational methods to simulate the mechanical properties and behaviors of cells, offering a high degree of accuracy in representing biological processes. These models are built upon principles of continuum mechanics and incorporate parameters representing cellular material properties, external forces, and intercellular interactions. The computational framework typically involves discretizing the cell and its surrounding environment into elements, then solving equations governing deformation and force balance. This allows researchers to predict cellular responses to stimuli, analyze cell-cell interactions, and investigate the biophysical factors influencing cell shape and movement with a level of detail difficult to achieve through purely experimental means. The fidelity of DCMs is determined by the complexity of the underlying physics and the resolution of the numerical methods employed.

Deformable Cell Models (DCMs) utilize established biophysical principles to computationally predict cellular behavior. Osmotic pressure, arising from differences in solute concentration, drives volume changes and influences cell shape. Cortical tension, generated by the actin cytoskeleton, provides resistance to deformation and is critical for maintaining cell morphology and generating forces. Cell adhesion, mediated by surface receptors, governs interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix, impacting cell-cell and cell-substrate connectivity. The accurate representation of these forces within DCMs allows for the simulation of complex processes, including cell migration, morphogenesis, and tissue organization, with predictions validated through comparison to in vitro and in vivo observations.

Deformable Cell Models (DCMs) have been successfully implemented in simulations of bile canaliculi formation with a high degree of granularity, achieving up to 2600 nodes per cell. This computational resolution allows for detailed modeling of the complex biophysical mechanisms driving canaliculi assembly, including cell-cell interactions, membrane deformation, and the influence of cytoskeletal forces. The high node count enables the simulation of intricate cellular morphologies and dynamics, providing a platform to investigate the roles of specific parameters and forces in regulating canaliculi formation. This level of detail is crucial for understanding the underlying biophysics and testing hypotheses related to liver development and disease.

Deformable Cell Model (DCM) simulations of bile canaliculi formation have yielded structures visually comparable to those observed in experimental imaging. Specifically, simulated cellular arrangements, including the formation of lumenized networks and cellular morphology, exhibit qualitative similarities to images of developing bile canaliculi in vitro and in vivo. This visual resemblance provides a level of validation for the model’s biophysical parameters and computational approach, suggesting the simulations accurately capture key aspects of the underlying biological processes driving canaliculi morphogenesis. While not quantitative, the qualitative agreement supports the use of DCMs as a predictive tool for investigating the biophysical mechanisms of bile canaliculi formation and potentially other cellular network formations.

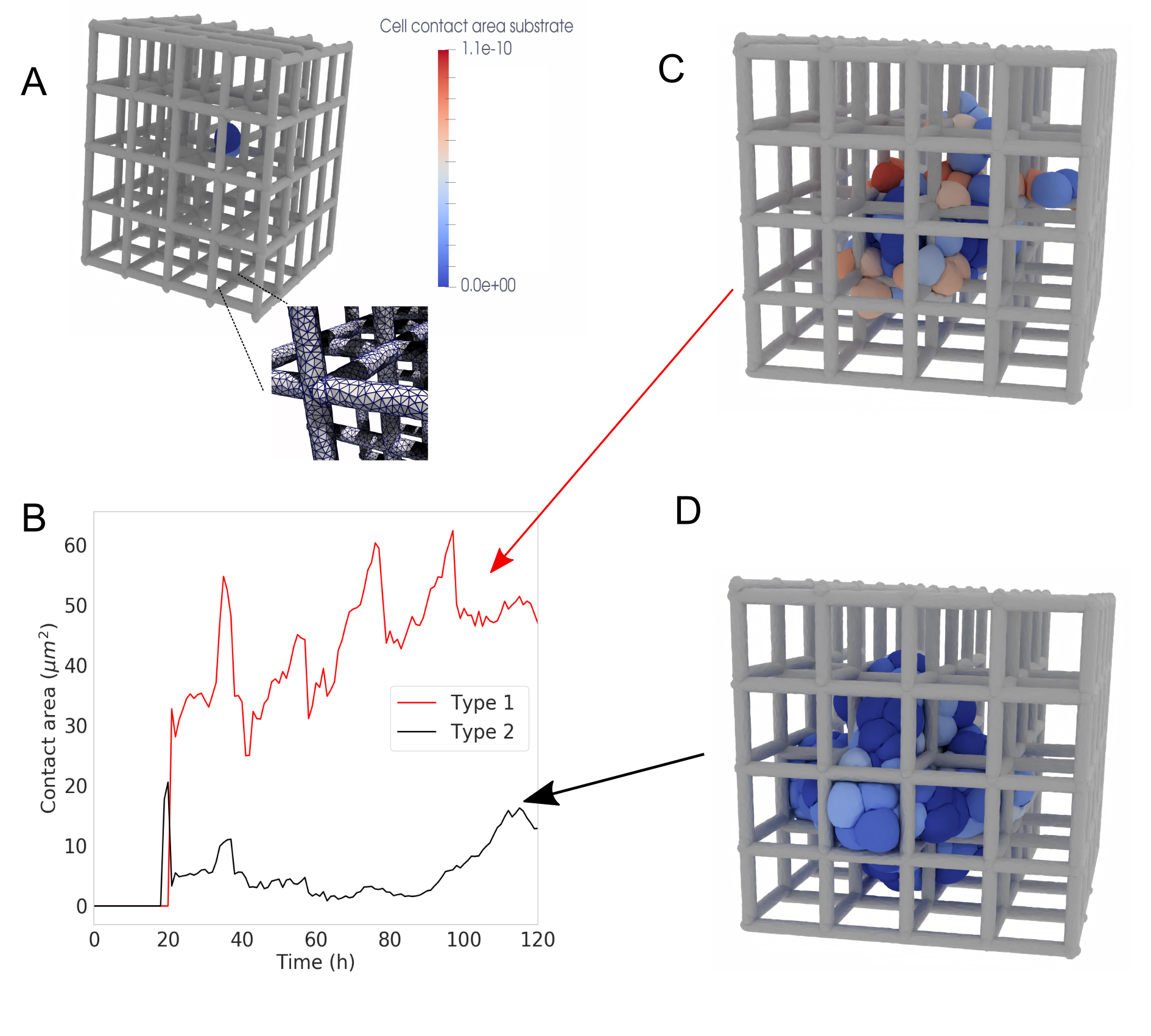

![Simulations of a cell monolayer reveal that higher cell-substrate adhesion energy maintains cellular integrity and pressure [latex] ext{(type 2, right)}[/latex], while lower adhesion leads to cell detachment, apoptosis [latex] ext{(brown)}[/latex], and decreased average cell pressure [latex] ext{(type 1, left)}[/latex].](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15273v1/Figures/Fig1.png)

Scaling Biological Insights: Agent-Based Modeling for Complex Systems

Agent-Based Models (ABMs) offer a computationally efficient alternative to traditional, continuum-based Dynamic Compartment Models (DCMs) by discretizing the system into autonomous entities, termed “agents,” which represent individual cells or subcellular components. Instead of solving partial differential equations that describe the average behavior of a population, ABMs simulate the interactions of these agents according to defined rules within a specified environment. This approach reduces computational demands because calculations are performed only for individual agents and their immediate neighbors, rather than across the entire modeled domain. The efficiency of ABMs stems from focusing on local interactions and emergent global behaviors, enabling simulations of larger systems and longer timescales than are typically feasible with DCMs.

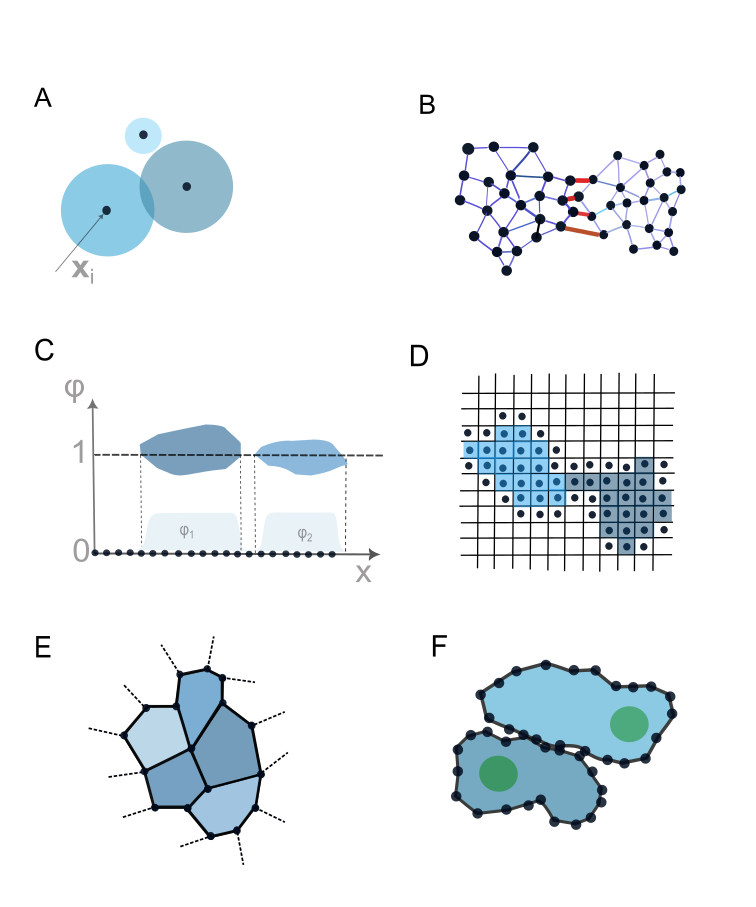

Agent-based modeling encompasses several distinct approaches that trade off simulation detail for computational efficiency. Vertex Models represent cells as polygons, defining cell shape and movement through vertex adjustments; these are relatively computationally inexpensive but may lack detailed intracellular representation. Cellular Potts Models (CPM) utilize a grid-based system where cells are defined by clusters of grid cells, minimizing interface energy to simulate cell behavior – offering a balance between detail and speed. Subcellular Element Methods (SEM) take a more granular approach, explicitly modeling subcellular components and their interactions, providing the highest level of detail but at a significantly increased computational cost; SEM is suitable for investigating specific intracellular mechanisms but is less scalable for large-scale simulations compared to Vertex Models or CPM. The choice of method depends on the specific biological question and available computational resources.

TiSim is a software package designed to enable the implementation and execution of agent-based modeling (ABM) simulations of cellular behavior at scale. It provides a framework for defining agent properties, spatial environments, and interaction rules, and supports parallel computing architectures to manage the computational demands of large-scale simulations. The software utilizes a scene graph-based representation to efficiently handle geometric data and supports a scripting language for defining complex simulation workflows. TiSim’s architecture allows researchers to model populations of cells – numbering in the millions – and observe emergent behaviors resulting from individual agent interactions, facilitating investigations into phenomena like tissue morphogenesis, cancer progression, and immune responses.

Bridging Scales: Integrating Simulation with Spatial Biological Data

Computational modeling of complex biological systems often relies on detailed, computationally expensive deterministic models (DCMs). However, recent advances leverage surrogate models – essentially, learned approximations of these DCMs – to drastically reduce processing time. These simplified models are trained using the output of their more complex counterparts, effectively capturing the essential relationships within the data without the need for repeated, intensive calculations. This approach allows researchers to maintain a high degree of predictive accuracy while achieving substantial computational savings, opening doors to faster iterations and broader exploration of parameter space. The resulting efficiency is crucial for simulating large-scale biological processes and integrating these simulations with other data sources, such as spatially resolved genomic information.

Biological tissues are rarely uniform; variations in cell states and molecular profiles across even small distances can dramatically influence function and response to stimuli. Recent advancements now enable the creation of simulations that reflect this inherent tissue heterogeneity by integrating reduced-order models – computationally efficient surrogates of complex biological models – with data from Spatial Genomics. This fusion allows researchers to move beyond averaging effects and generate spatially resolved predictions, effectively visualizing how processes unfold at specific locations within a tissue. By incorporating the precise molecular landscape revealed by Spatial Genomics, these simulations can capture localized differences in behavior, providing a more nuanced and realistic depiction of tissue dynamics than previously possible, and ultimately enhancing the predictive power of in silico experimentation.

The convergence of reduced-order modeling and spatial genomics is revolutionizing biological inquiry by enabling investigations into the intricate dynamics of living tissues. This integrated approach moves beyond traditional, homogenized analyses to reveal how cellular interactions and local environments influence developmental processes, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic outcomes. By simulating biological systems with spatially resolved detail, researchers can now explore how variations within a tissue – in gene expression, protein distribution, or mechanical cues – contribute to overall function and dysfunction. Consequently, this holistic perspective facilitates a deeper understanding of complex biological phenomena, from the branching of embryonic tissues to the spread of cancerous tumors and the effectiveness of targeted drug delivery – ultimately promising more precise and effective biomedical interventions.

A core ambition of this integrated framework centers on accelerating the pace of biological discovery through simulations that outrun real-world experimentation. By drastically reducing computational demands – aiming for simulation times faster than those required to execute a corresponding physical experiment – researchers can explore a far wider range of biological conditions and interventions in silico. This capability doesn’t simply offer speed; it facilitates a “digital twin” approach to bioengineering, where a virtual representation of a tissue or organism can be iteratively tested and refined. Such a paradigm allows for predictive modeling of complex biological processes, from developmental biology and disease progression to personalized drug responses, ultimately enabling more targeted and efficient bioengineering strategies and potentially revolutionizing the design of new therapies.

![DCM simulations reveal that spheroids with stiffer cortical properties ([latex]E_{cor}[/latex]) exhibit a radial pressure gradient, shielding inner cells from external compression, while those with softer cortices distribute pressure more evenly throughout the spheroid.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15273v1/Figures/Fig1a.png)

The pursuit of understanding tissue development, as detailed in this work regarding the Deformable Cell Model, echoes a fundamental principle of scientific inquiry. It’s a refinement of observation and calculation, striving for predictive accuracy. As Isaac Newton famously stated, “I have not been able to discover the composition of any mixed body, though I have tried it many ways.” This sentiment resonates with the challenges addressed by agent-based modeling; dissecting the complex interplay of cellular mechanics and organization requires continuous refinement and a commitment to uncovering the underlying principles governing multicellular systems. The DCM, by focusing on individual cell behaviors, offers a powerful approach to building from simple rules to emergent tissue-level properties – a modern echo of Newton’s own quest for fundamental understanding.

Where Beauty Scales

The proliferation of agent-based models, particularly those employing deformable cell mechanics, has yielded simulations of increasing fidelity. Yet, the pursuit of photorealistic rendering – of mimicking appearances – risks overshadowing the elegance of underlying principles. The true measure isn’t how closely a simulation looks like biology, but how parsimoniously it explains it. Current models often accrue parameters as attempts to address every observed quirk, resembling baroque ornamentation more than functional design. Refactoring, editing – not rebuilding – is paramount.

A significant, and frequently overlooked, limitation remains the challenge of validation. While models can generate predictions, translating these into experimentally testable hypotheses requires careful consideration. The temptation to interpret any correspondence as confirmation must be resisted. Rigorous comparison with quantitative data, ideally gathered across multiple scales, will distinguish genuinely insightful models from those merely capable of recapitulating known facts.

The future likely lies in models that prioritize generalization. The goal isn’t to create a unique simulation for every tissue or cell type, but rather to identify the core biophysical principles that govern multicellular organization. Beauty scales – clutter doesn’t. A truly successful model will be simple enough to understand, yet powerful enough to illuminate the extraordinary complexity of life.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15273.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

2026-01-22 21:40