John Carpenter has this one recurring nightmare.

He describes a recurring dream where he’s lost in a large, unfamiliar city, searching for the movie theaters, only to find they’re all shut down. That’s the essence of the dream, he says.

I met John Carpenter at his Hollywood studio on a beautiful October afternoon. Near his chair were a classic “Halloween” pinball machine and a large statue of Nosferatu. I joked that a psychoanalyst like Freud would have a field day analyzing those items as dream symbols.

“No, I know,” he says, laughing. “I don’t have too much trouble with that either.”

Despite everything, the experience still bothers him deeply. He explains that it frequently appears in his dreams: he’s with loved ones or friends, wanders off, and becomes completely lost. He jokingly suggests that Freud would easily understand the meaning, adding that it’s not a particularly complicated feeling.

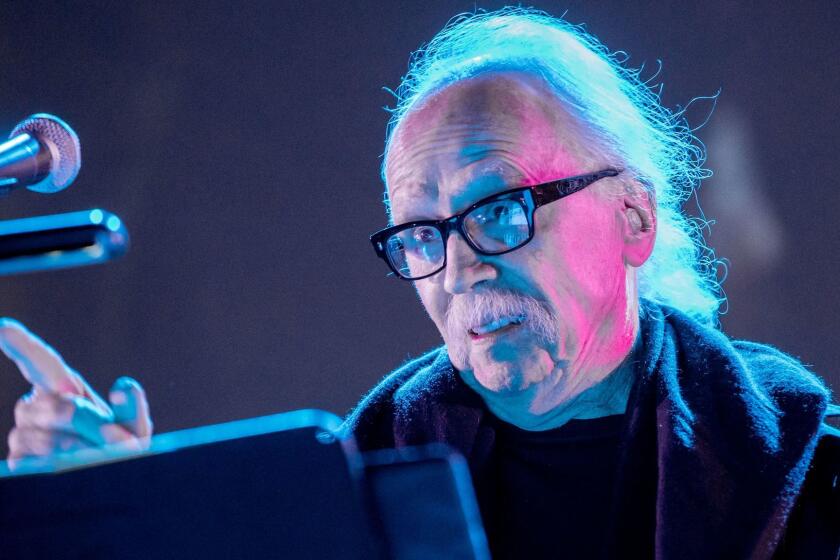

Now 77, director John Carpenter is known for being direct, but still friendly. He’s largely stepped back from filmmaking, with his last movie being 2010’s “The Ward.” While he chose to slow down, the film industry also made it difficult to continue. During my visit, Carpenter mentioned the recent death of Drew Struzan, the talented movie poster artist he admired – particularly Struzan’s memorable painting for Carpenter’s 1982 film, “The Thing.” It struck Carpenter, and me, how much the art of hand-painted movie posters has disappeared.

“The whole movie business that I knew, that I grew up with, is gone,” he replies. “All gone.”

Despite the challenges he’s faced, John Carpenter still happily lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Sandy King. She runs Storm King Comics, a graphic novel publisher that Carpenter also contributes to. He’s remained visible, appearing on John Mulaney’s Netflix series, “Everybody’s in L.A.,” and recently received a Career Achievement Award from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. This recognition feels overdue, considering he was largely overlooked after the box office disappointment of “The Thing,” and never received an Oscar nomination despite his long and influential career.

Besides enjoying Warriors basketball and video games, John Carpenter is currently very busy with music. He’s performing live concerts of his famous film scores and instrumental albums, alongside his son Cody and godson Daniel Davies, at the Belasco Theater downtown this weekend and next.

John Carpenter is far better known for his iconic, electronic music scores – like those in “Halloween” and “Escape from New York” – than for his work as a director. He’s actually scored many more films than he’s directed, even recently agreeing to compose the music for Bong Joon Ho’s upcoming movie. In 2025, his musical influence is much clearer and more widely appreciated than his filmmaking style.

John Carpenter’s signature sound – a blend of retro electronic music with a hypnotic, rhythmic feel – has become hugely influential. You can hear its echoes in everything from the soundtrack to “Stranger Things” to the music of “F1,” and many other contemporary artists are trying to capture the same vibe, especially with his four ‘Lost Themes’ albums leading the way.

Most modern composers aren’t aiming for the style of John Williams anymore; they’re more interested in the sound of John Carpenter. Carpenter, a Kentucky native known for his skepticism and long white hair, disagrees when I point this out.

“Well, see, I must be stupid,” he says, “because I don’t get it.”

Carpenter often dismisses his own musical talent. He claims he only composed his film scores because he couldn’t afford to hire anyone else, and that he used synthesizers simply because they were inexpensive and he lacked the ability to write for a full orchestra. However, when I mentioned that Daniel Wyman, who assisted with the original “Halloween” score, complimented Carpenter’s strong understanding of fundamental music theory – specifically, concepts like the ‘circle of fifths’ and secondary dominants that built suspense in his music – Carpenter brushed it off.

“I honestly don’t understand what he means,” Carpenter admitted with a bit of a playful, mischievous tone. “It probably all stems from listening to classical music with my dad in the living room when I was growing up. I guess I’m just remembering all of that now.”

John Carpenter seemed to naturally inherit his musical talent from his father, Dr. Howard Carpenter, a skilled violinist and composer. Growing up in Bowling Green, their home was always filled with classical music, and young John was particularly captivated by Bach. He often said, “Bach, Bach, and Bach – he’s my favorite. I just love Johann!”

That’s a great point. Bach’s music has a captivating, repeating quality, and the pipe organ – with its echoing sound in large cathedrals – was essentially the first synthesizer.

According to Carpenter, Bach is a timeless musical genius. He’s particularly fond of the pieces known as ‘St. Anne’ and the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. While acknowledging the brilliance of composers like Mozart and Beethoven – especially Beethoven – Carpenter feels a stronger connection to Bach’s music. He says he understood and appreciated Bach’s work instantly.

John Carpenter has always been passionate about film scores. He particularly admires the early electronic music in the 1956 film “Forbidden Planet,” and considers Bernard Herrmann and Dimitri Tiomkin to be his favorite composers. He points to Tiomkin’s work on the 1951 sci-fi classic “The Thing From Another World” – specifically how the music shifts from a traditional western fanfare to a dramatic, ominous orchestral piece during the opening titles – as a prime example of his skill. Carpenter later remade this film as “The Thing.”

“The music is so weird, I cannot follow it,” he says. “But I love it.”

Carpenter has a deep personal connection to rock ‘n’ roll, citing the Beatles, the Stones, and the Doors as major influences. From high school, when he first got a guitar and grew his hair long, he dreamed of being a rock star. He gained performance experience singing R&B and psychedelic rock for college sororities and even toured U.S. Army bases in Germany. Later, while at USC, he formed a rock trio called Coupe de Villes, and they recorded an album and played at various wrap parties.

Carpenter continued to draw inspiration from current music. While scouting locations for “Halloween,” he listened to Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London.” Peter Fonda later connected them, and Carpenter was excited about the possibility of turning the song into a movie – with Fonda playing the werewolf and getting a happy ending, as Carpenter remembers. Later, in the 1980s, he and his sons often listened to Metallica, and he remains a fan of Devo to this day.

Entertainment & Arts

As a child, John Carpenter discovered some music paper and began composing enthusiastically, as he described it.

It’s unusual for a film director to also compose the music for their movies, and even more uncommon for them to have a long career performing music on stage. These two roles typically require very different types of people.

Growing up, music was always a big part of my family because my dad was a performer,” Carpenter explains. But even with that background, he didn’t start touring with his own music until 2016, and he struggled with intense stage fright beforehand. He recalls a difficult experience in a high school play where he forgot his lines, which was deeply embarrassing and left him feeling scared for a long time.

The director credits his touring drummer, Scott Seiver, for helping him beat it.

He says the music instantly transports him, creating an incredible energy. It’s like being in the middle of a huge, excited crowd – a truly amazing experience.

He pushes back against the idea that directors “hide behind the camera.”

The biggest challenge is the pressure,” Carpenter explains. “You’re not only feeling it from the studio, but you’re also responsible for a lot of money and a whole crew, and everyone wants to stay on schedule.”

He recalls watching rough cuts of his work on “Ghost of Mars” in 2001 and realizing he was pushing himself too hard. He decided he needed to stop. “I couldn’t keep doing that to myself,” he explains. “The stress was overwhelming – it could ruin you, like it has so many directors.” He found relief in music, which he describes as a gift from a higher power.

John Carpenter acknowledges being thankful, but doesn’t have religious beliefs. He envisions death as a return to the universe – a dispersal of energy, essentially returning us to stardust. He sees this as a natural process originating from the darkness of space, something we need to accept. He explains that death is a complete stop – the heart, brain, and all functions cease, and energy simply fades away. For Carpenter, that’s simply ‘The End’.

This is not exactly a peaceful thought for him.

He admitted he doesn’t want to die and isn’t eager to face it, but accepts he has no control over the situation. He feels strongly about his own beliefs, even though he knows he’s the only one who holds them, and doesn’t want to impose them on others, recognizing everyone has their own faith and vision of what comes next.

He describes himself as a “long-term optimist but a short-term pessimist.”

“I have hope,” he says, “put it that way.” Yet he looks around and sees a lot of evil.

According to Carpenter, who often uses films to criticize those in power, the worst evils aren’t natural disasters, but rather the actions of people. While nature can be harsh, he argues that humans are uniquely capable of cruelty, even finding enjoyment in it, whether for personal gain or simply to exert power. Despite this capacity for evil, Carpenter also believes humans are capable of incredible kindness and are responsible for the creation of music, which he considers the highest form of art.

The greatest?

He admits he doesn’t enjoy discussing movies, preferring to simply experience them. While it’s not his personal preference, he believes cinema is a timeless art form that has endured for generations.

He’s always found more success and satisfaction with music than with movies. Recently, the film industry disappointed him when A24 rejected his finished score for “Death of a Unicorn” – thankfully, he still owns the rights and plans to release it soon. Besides enjoying live performances, he’s currently creating a complex heavy metal album called “Cathedral,” which includes spoken dialogue, and he’ll be previewing parts of it at the Belasco Theater.

This piece is like a musical movie, inspired by a dream John Carpenter once had – though it’s not a frightening one for him. What truly scares Carpenter is the feeling of losing control.

He experienced this feeling while acting, and it’s becoming more common as he gets older and faces the challenges of aging. It also reminds him of a recurring nightmare: being lost in a large city and unable to find a movie theater.

He admits there’s nothing he can really change about the situation. He explains that he can only focus on the things he can control – making music and enjoying basketball.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- ‘SNL’ host Finn Wolfhard has a ‘Stranger Things’ reunion and spoofs ‘Heated Rivalry’

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2025-10-23 13:37