Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that the deepest layers of large language models organize information geometrically, and this structure directly powers their predictive abilities.

Late layers of large language models exhibit angular representational geometry causally linked to prediction, distinguishing them from earlier layers with more general geometric properties.

Despite the remarkable capabilities of large language models, the computational mechanisms underlying their predictive abilities remain largely opaque. This work, ‘Depth-Wise Emergence of Prediction-Centric Geometry in Large Language Models’, reveals a depth-wise transition in LLM representations, wherein later layers organize information geometrically to directly parameterize prediction distributions. Specifically, we demonstrate that angular organization within representational space encodes predictive similarity, while earlier layers retain more general contextual information. Does this emergence of prediction-centric geometry represent a fundamental principle of intelligent computation, and how might it inform the design of more interpretable and controllable AI systems?

Mapping the Geometry of Thought in Large Language Models

Despite their increasingly impressive performance on a wide range of tasks, Large Language Models (LLMs) function as remarkably complex systems whose internal logic remains largely inaccessible. This opacity presents significant challenges for both understanding how these models arrive at their conclusions and for exerting meaningful control over their behavior. While LLMs can generate coherent text, translate languages, and even write different kinds of creative content, the processes driving these abilities are hidden within billions of parameters. Consequently, diagnosing errors, mitigating biases, or ensuring predictable outputs proves exceptionally difficult, hindering the development of truly reliable and trustworthy artificial intelligence. The inability to readily interpret the model’s reasoning limits opportunities for optimization beyond simply scaling up size and data, and ultimately restricts the potential for building more efficient and adaptable systems.

The capacity of Large Language Models to process and generate human-quality text relies on complex internal representations of information, and understanding the structure of these representations – essentially, the ‘geometry of thought’ within the model – is proving vital for advancements in both performance and reliability. Rather than simply treating LLMs as functional input-output systems, researchers are now mapping the high-dimensional spaces where concepts and knowledge are encoded. This geometric perspective reveals how different pieces of information relate to one another within the model, offering insights into how LLMs generalize, reason, and potentially, where they fail. By characterizing the shape of this internal knowledge landscape, it becomes possible to identify biases, vulnerabilities, and opportunities for optimization, ultimately leading to more robust, efficient, and trustworthy artificial intelligence systems.

For years, investigations into Large Language Models have largely treated them as inscrutable “black boxes” – systems capable of impressive feats, yet resistant to internal examination. However, a burgeoning field now proposes visualizing the internal states of these models as a high-dimensional geometric landscape. This approach doesn’t focus on what an LLM knows, but how it’s organized; concepts are represented as points in this space, with related ideas clustered together. By mapping these internal representations, researchers can begin to understand how LLMs categorize information, draw analogies, and even make errors, offering a potential pathway to not only interpret their reasoning but also to refine their architecture for enhanced performance and control. This geometric perspective transforms the LLM from an opaque system into a navigable terrain of knowledge, promising a deeper understanding of artificial intelligence itself.

Current advancements in Large Language Models (LLMs) heavily rely on simply increasing model size – a computationally expensive and ultimately limited strategy. However, a geometric approach to understanding LLMs offers an alternative pathway, suggesting that improvements can be achieved not just through scale, but through optimizing the structure of knowledge representation. By mapping the internal ‘cognitive space’ of these models, researchers can identify redundancies, inefficiencies, and potential bottlenecks in how information is processed. This allows for the development of techniques that streamline computations, reduce energy consumption, and enhance the model’s ability to generalize – ultimately leading to LLMs that are both more powerful and more manageable than those built solely on brute-force scaling. The promise lies in crafting models where knowledge is organized in a more intuitive and accessible manner, unlocking a new era of efficient and controllable artificial intelligence.

A Geometric Toolkit for Probing LLM Representations

Geometric analysis of Large Language Model (LLM) token representations utilizes established mathematical tools to quantify relationships between tokens in the model’s embedding space. Cosine Similarity, calculated as the cosine of the angle between two vectors, measures the similarity of their orientation, ranging from -1 (opposite) to 1 (identical). Euclidean Distance, calculated as the straight-line distance between two vectors, provides a magnitude-based measure of dissimilarity. Angular Distance, representing the angle between two vectors, focuses solely on directional difference, independent of magnitude. These metrics, applied to the high-dimensional vector representations of tokens, allow for the characterization of representational similarity and the identification of clusters or patterns within the model’s learned space. [latex] \text{Cosine Similarity} = \frac{\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B}}{\|\mathbf{A}\| \|\mathbf{B}\|} [/latex], [latex] \text{Euclidean Distance} = \sqrt{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (A_i – B_i)^2} [/latex].

Quantifying geometric properties of token representations allows for the characterization of the high-dimensional representational space within Large Language Models (LLMs). Specifically, measures like Cosine Similarity, Euclidean Distance, and Angular Distance provide a means to assess the relationships between token embeddings; lower Euclidean and Angular distances, and higher Cosine Similarity, indicate greater semantic relatedness. Analyzing the distribution of these distances and similarities across the representational space reveals patterns in how LLMs organize and encode information. Furthermore, metrics such as Participation Ratio and Dimensionality quantify the effective number of dimensions used in these representations, indicating how efficiently information is distributed and utilized within the model’s parameters. These geometric analyses offer a quantifiable basis for understanding the structure and organization of knowledge captured by LLMs.

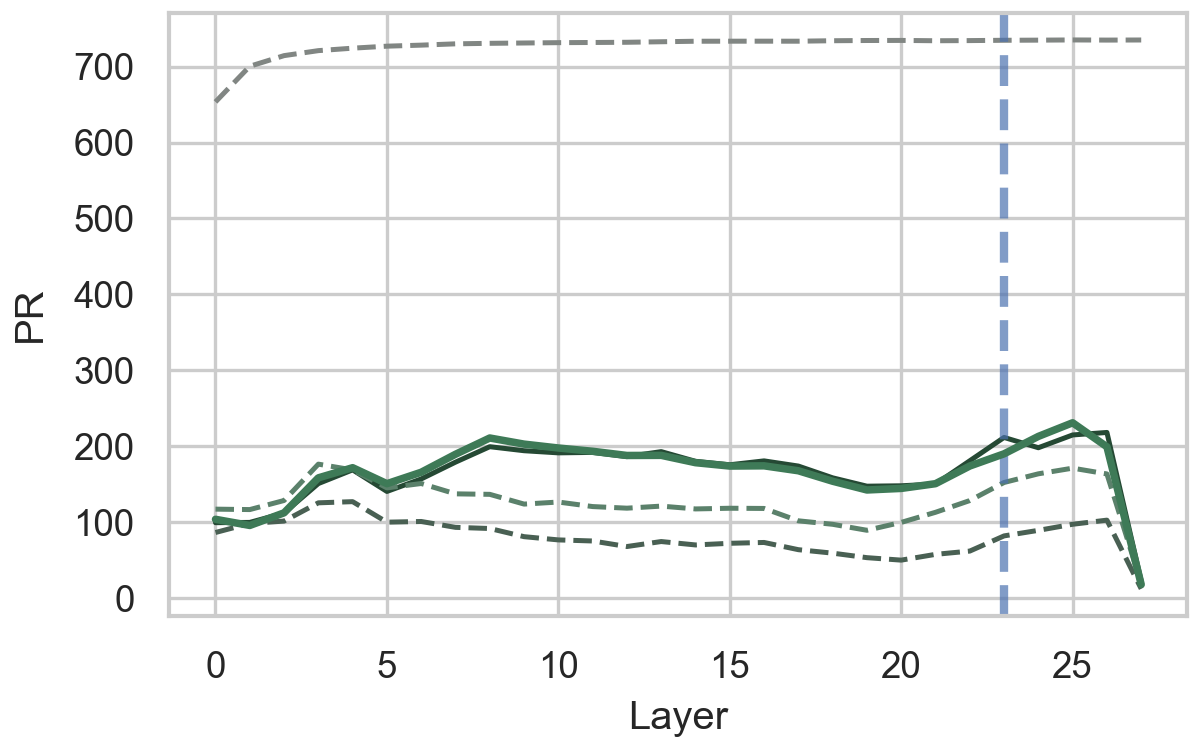

Participation Ratio (PR) and dimensionality analysis quantify the extent to which different dimensions of a layer’s activation vectors contribute to representing information; a lower PR indicates that information is encoded using fewer dimensions, suggesting efficient representation. Specifically, PR is calculated as [latex]1 – \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{d} (\sigma_i)^2}{\sum_{i=1}^{d} (\sigma_i)^2}[/latex], where [latex]\sigma_i[/latex] represents the variance of the i-th dimension across a dataset. Higher dimensionality, conversely, may indicate redundancy or overparameterization. Analysis of these metrics across layers reveals that early layers often exhibit higher effective dimensionality, while later layers tend to consolidate information into a lower-dimensional subspace, indicating a shift in representational strategy during processing.

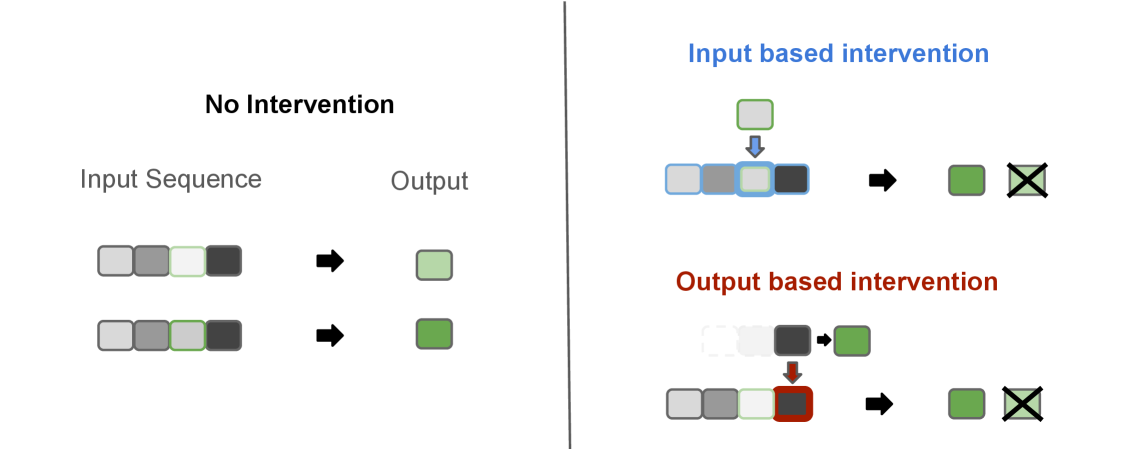

Analysis of layer-wise intervention effectiveness demonstrates a distinct two-phase computational organization within Large Language Models. Specifically, interventions focused on input features – manipulating or ablating tokens related to the initial prompt – exhibit the strongest impact on model behavior in the early layers, comprising approximately the first two-thirds of the network’s depth. Conversely, interventions centered around prediction – altering the model’s generated output or internal prediction signals – become increasingly dominant in the later layers, constituting roughly the final one-third. This suggests an initial processing stage dedicated to encoding input information, followed by a subsequent stage primarily focused on generating and refining predictions based on that encoded representation.

Steering the Model’s ‘Thought’ Through Intervention-Based Analysis

Intervention-Based Analysis is a technique used to understand the causal mechanisms within Large Language Models (LLMs) by systematically altering internal activations and observing the resulting changes in the model’s output. This process involves modifying the numerical values representing information at various layers of the LLM – essentially ‘perturbing’ the model’s internal ‘thought’ process. By quantifying how these perturbations affect the predicted output, researchers can infer the influence of specific internal representations on the model’s decisions. The magnitude and nature of the output change directly correlate to the causal importance of the intervened representation; larger changes indicate a more significant role in the prediction process. This allows for the identification of key features and pathways driving the model’s behavior, offering insights beyond simple input-output correlations.

Input-centric intervention modifies the internal representation of input tokens before they propagate through the model, effectively altering the information the model receives. This is contrasted with output-centric intervention, which directly manipulates the activations immediately preceding the final prediction layer, influencing the probability distribution over possible output tokens. Both approaches aim to isolate the causal effect of specific internal representations on the model’s generated text; however, input-centric methods assess how changes to the initial processing stage affect downstream predictions, while output-centric methods examine the impact of directly altering the model’s immediate decision-making process.

The Months Task, utilized for intervention-based analysis, presents a controlled evaluation of language model performance by requiring prediction of the next month in a sequence – for example, given “January, February,” the model is expected to output “March.” Its robustness stems from the task’s deterministic nature and limited vocabulary, allowing for precise measurement of prediction divergence following internal representation perturbations. This deterministic quality simplifies the identification of causal relationships between specific model activations and output changes, offering a clear signal for assessing the impact of input-centric and output-centric interventions. The task’s simplicity also enables efficient computation and large-scale experimentation, facilitating statistically significant conclusions regarding the effectiveness of different intervention strategies.

Analysis of intervention-based experiments reveals a statistically significant positive correlation between Angular Distance – a measure of the angle between perturbed and original vector representations – and prediction divergence in the later layers of the Large Language Model (LLM). This indicates that changes in the direction of these internal vectors have a pronounced effect on the model’s output. Conversely, Euclidean Distance, which quantifies the magnitude of difference between vectors, demonstrates no consistent correlation with prediction divergence. This suggests that the magnitude of the internal vector representations is less critical to the prediction process in later layers than their directional component, implying that angular geometry plays a crucial role in how the model processes and utilizes information as it nears the output stage.

Towards Mechanistic Understanding and Robust Large Language Models

Mechanistic Geometry represents a significant advancement in dissecting the inner workings of large language models by establishing a direct connection between the geometric organization of their internal representations and their capacity to control predictions. Unlike previous methods that primarily focused on correlation, this approach leverages tools from geometry and causal inference to pinpoint specific representational dimensions – angles and distances within the model’s high-dimensional space – that demonstrably cause changes in the generated output. By treating these representational spaces as geometric objects, researchers can identify which directions correspond to specific concepts or features, and then manipulate those directions to steer the model’s predictions with precision. This causal link, revealed through targeted interventions and analyses, moves beyond simply observing what a model does to understanding how it achieves its results, opening avenues for improved interpretability, robustness, and ultimately, more reliable artificial intelligence systems.

A deeper comprehension of the connections between representational geometry and causal control within large language models unlocks the potential for precisely targeted interventions. Rather than treating these models as opaque ‘black boxes’, researchers are now able to pinpoint specific neural circuits responsible for particular predictions, allowing for adjustments that enhance model robustness against adversarial attacks and improve generalization to unseen data. This approach moves beyond simply improving overall performance metrics; it facilitates the development of models that are demonstrably more reliable and predictable in their responses, fostering greater trust and usability. By strategically manipulating these identified circuits, developers can address biases, correct factual inaccuracies, and ultimately create language models capable of more nuanced and dependable reasoning.

Recent large language models, including Llama, Mistral, and Qwen, are increasingly amenable to precise manipulation and enhancement through techniques rooted in mechanistic interpretability. These methods move beyond simply observing model behavior to actively dissecting and controlling the internal computations that drive predictions. By identifying specific neural circuits responsible for particular functions, researchers can directly optimize these circuits to improve performance on targeted tasks, enhance robustness against adversarial attacks, and even steer the model’s reasoning process. This fine-grained control allows for interventions far beyond traditional fine-tuning, offering the potential to build more reliable, explainable, and adaptable language models capable of solving complex problems with greater efficiency and trustworthiness.

Recent investigations into large language models reveal a distinct two-phase computational structure. Initial layers appear dedicated to processing contextual information, effectively building an internal representation of the input without directly influencing the final prediction. However, subsequent, later layers demonstrate a markedly different behavior, exhibiting angular geometry that is demonstrably causally linked to the model’s output. This suggests these later layers aren’t simply relaying information, but actively manipulating representations in a way that directly determines the predicted outcome. The separation of these functions-contextual processing versus prediction-driven manipulation-offers a potential blueprint for understanding how these complex models arrive at their conclusions and, crucially, for developing methods to improve their robustness and reliability.

The study’s findings regarding the late layers’ angular organization resonate with a timeless principle of system design. As Edsger W. Dijkstra observed, “It’s not enough to have good intentions; you must also have good tools.” This research provides a tool – geometric analysis, specifically focusing on angular coding – to understand how large language models achieve their predictive capabilities. The discovery that this angular structure is causally linked to prediction, unlike the more general geometry of earlier layers, suggests a refinement of architecture focused on maximizing predictive power. If the system looks clever – and a prediction-centric angular organization certainly hints at cleverness – it’s probably fragile. However, the causal link identified here hints at a robust, rather than merely clever, design choice.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The observation that prediction-centric geometry manifests primarily in the later layers of large language models is, predictably, not the full story. It suggests a developmental process-a layering of capabilities-but leaves the fundamental question of why this angular coding emerges unanswered. Is this an artifact of training procedures, a consequence of optimization landscapes, or does it reflect something inherent in the structure of information itself? The elegance of the geometric organization implies a principle at play, yet the system’s opacity resists easy dissection.

Future work must move beyond merely describing these representational geometries. Causal interventions, while illuminating, are blunt instruments. A more nuanced understanding requires methods capable of tracing information flow within layers, identifying the specific computations that give rise to angular separation, and determining whether this is genuinely a more efficient form of representation or simply a local optimum in a vast, high-dimensional space. If a design feels clever, it’s probably fragile.

Ultimately, the field risks becoming fixated on the what – the shapes and structures within these models – and neglecting the why. The true challenge lies in building models that are not merely predictive powerhouses, but systems whose internal logic is transparent and amenable to theoretical analysis. A simpler explanation, even if less immediately performant, will likely prove more robust in the long run.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04931.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

2026-02-08 12:31