Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research uncovers the underlying architecture of successful innovation networks, revealing a surprising interplay between tight-knit teams and broader organizational structures.

Analysis of innovation networks reveals a dual structure of cohesive teams and hierarchical organizations, impacting knowledge diffusion and technological inequality.

While innovation is widely understood to stem from collaboration, the underlying organizational principles of these networks remain largely unexplored. This research, presented in ‘The hidden structure of innovation networks’, investigates the mesoscale structure of inventive activity across artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and semiconductors, revealing a consistent duality of dense, recurrent inventor teams embedded within broader, hierarchically-organized firms. We demonstrate that this structure isn’t fully captured by standard network analysis techniques, and is strongly linked to the concentration of technological influence within specific network clusters. Does this suggest that understanding – and potentially influencing – these hidden hierarchies is crucial for fostering equitable and impactful innovation?

The Uneven Distribution of Innovation

The landscape of innovation is markedly uneven, with a disproportionate amount of knowledge creation concentrated within the hands of a small number of actors – leading institutions, dominant corporations, and a select group of researchers. This concentration isn’t merely a statistical observation; it raises fundamental questions about accessibility and equity in the production and dissemination of new ideas. While innovation historically benefits from collaborative efforts, current trends demonstrate a growing power imbalance, where control over key technologies and knowledge bases is increasingly centralized. Consequently, the potential for widespread societal benefit is hindered, as access to these advancements – and the capacity to build upon them – remains limited for many, creating a divide between those who shape innovation and those who primarily experience its effects. This skewed distribution necessitates a critical examination of the structures and incentives that perpetuate this imbalance, and exploration of strategies to foster more inclusive innovation ecosystems.

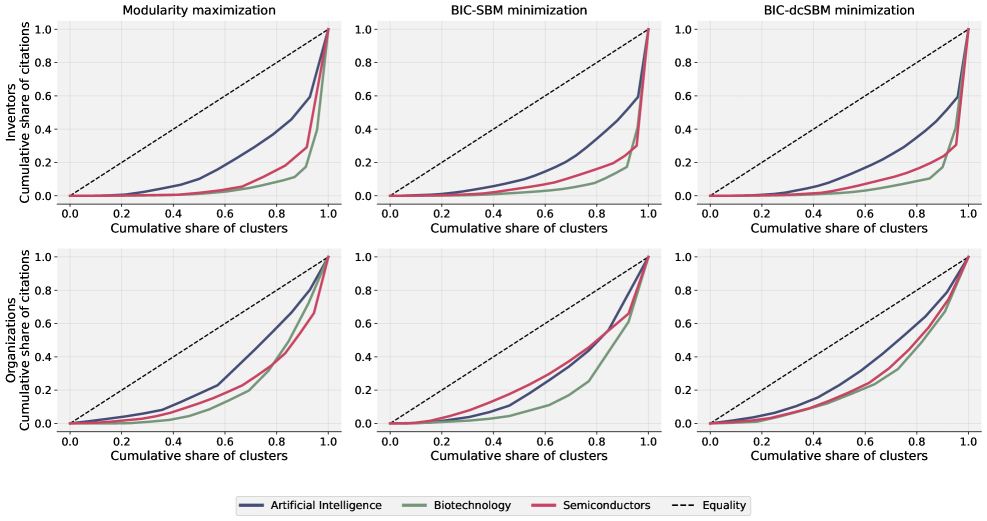

Conventional network analysis, while capable of mapping connections between innovators, often falls short in revealing the extent of knowledge concentration-how disproportionately certain actors dominate impactful contributions. This limitation is especially pronounced within the field of artificial intelligence, where a remarkably small number of institutions and individuals control the development and deployment of leading-edge technologies. Simply identifying connections doesn’t quantify the power imbalance; therefore, researchers are developing novel metrics-beyond simple node counts and degree centrality-to measure the true concentration of knowledge and its associated influence. These approaches aim to reveal not just who is connected, but how much of the critical knowledge resides within a select few, providing a more accurate picture of innovation inequality and informing strategies for more equitable distribution of resources and opportunity.

A concentrated landscape of innovation presents significant challenges to realizing the full potential of new technologies for societal benefit. When knowledge creation and technological advancement are held by a limited number of actors, the resulting innovations may not address the needs of a diverse population, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities. Fostering more inclusive innovation ecosystems – through strategies like open-source initiatives, broadened access to education and funding, and collaborative research – is therefore essential. These approaches aim to distribute knowledge creation more widely, ensuring that the benefits of progress are shared broadly and that innovation serves a wider range of societal challenges, rather than reinforcing existing power structures and concentrating wealth within a narrow segment of the population. Ultimately, a more equitable distribution of innovative capacity is not simply a matter of fairness, but a prerequisite for maximizing the positive impact of technology on the world.

Mapping the Structure of Innovation Networks

Innovation networks are constructed through the analysis of co-inventorship and intellectual property ownership records, providing a quantifiable map of collaborative relationships within technological fields. These networks demonstrate that knowledge is rarely created in isolation; instead, innovation frequently arises from the combination of expertise and resources held by multiple actors. Co-inventorship data, specifically, identifies direct collaboration between individuals, while shared patent ownership reveals broader organizational connections and the transfer of intellectual property rights. The resulting network structures allow researchers to trace the flow of knowledge, identify key intermediaries, and understand how information diffuses across different organizations and individuals contributing to technological advancement.

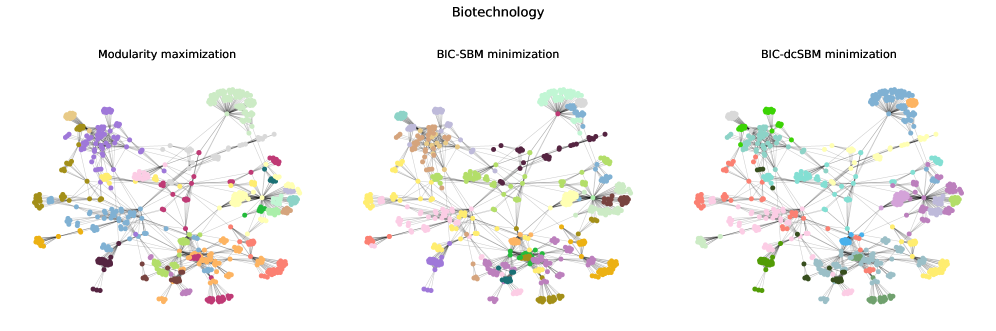

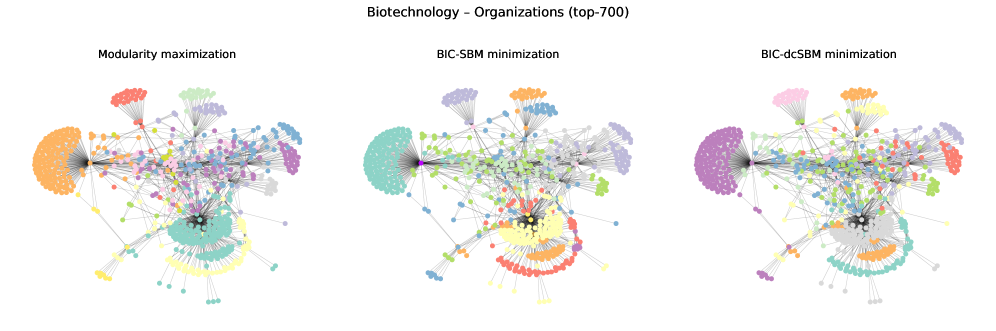

Innovation networks consistently demonstrate non-random structures, notably exhibiting Community Structure, Core-Periphery Structure, and Small-World Network properties. Community Structure indicates the presence of densely interconnected groups of actors with sparser connections between groups, fostering specialized knowledge development. Core-Periphery Structure defines a network with a central ‘core’ of highly connected actors and a less connected ‘periphery’, influencing information flow and control; the core often represents established entities, while the periphery allows for novel contributions. Small-World Networks are characterized by high clustering and short path lengths, enabling rapid diffusion of information across the network due to a combination of local connections and a few long-range links; this facilitates both redundancy and efficient knowledge transfer, impacting the speed and reach of innovation.

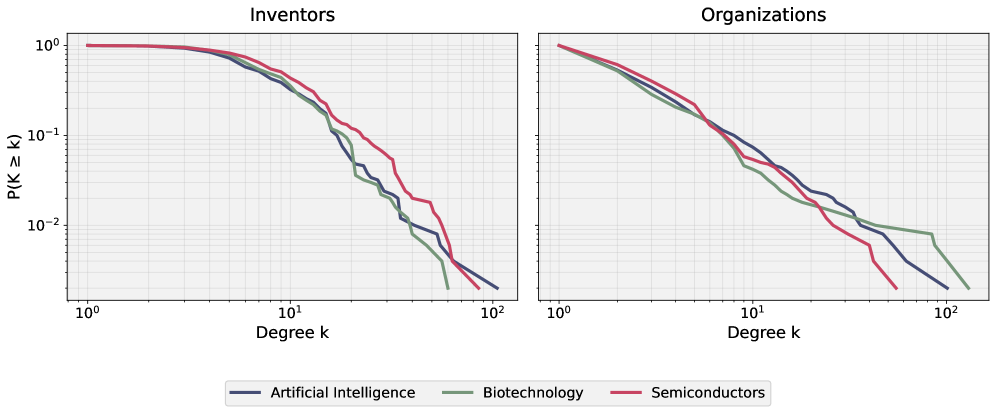

Network density and the clustering coefficient are key metrics for characterizing the structure of innovation networks. Network density, calculated as the ratio of existing connections to all possible connections, indicates the overall interconnectedness of the network. The clustering coefficient measures the degree to which nodes tend to cluster together; a higher coefficient suggests strong local connections. Analysis of inventor networks in areas like Artificial Intelligence reveals a density of approximately 0.018, alongside a significantly higher clustering coefficient compared to organization networks. This indicates that inventors exhibit greater internal cohesion and a tendency to collaborate with directly connected peers, fostering rapid knowledge diffusion within their immediate network.

Refining Community Detection: A Necessary Precision

The Stochastic Block Model (SBM) is a generative model for networks where nodes are assigned to latent communities, and edges are created with probabilities dependent on the community memberships of the connected nodes. While effective on networks with relatively uniform degree distributions – where most nodes have a similar number of connections – standard SBM implementations struggle with networks exhibiting heterogeneity in node degrees. This limitation arises because the basic SBM assumes a consistent connection probability within each community, failing to account for the presence of “hub” nodes with significantly more connections than average. Consequently, the model’s ability to accurately infer community structure diminishes in networks where degree variance is high, leading to misclassification of nodes and inaccurate identification of community boundaries.

The Degree-Corrected Stochastic Block Model (DC-SBM) improves upon the standard SBM by explicitly modeling the heterogeneous degree distributions frequently observed in real-world networks. Standard SBM implementations assume uniform degree within communities, which often leads to inaccurate community assignment when nodes exhibit varying connectivities. The DC-SBM introduces correction factors to the probability of connection between nodes, based on their expected degrees, \theta_i and \theta_j . This correction alters the connection probability from B_{ij} to B_{ij} \sqrt{\frac{\theta_i \theta_j}{(\sum_k \theta_k)^2}} , effectively accounting for degree biases and enhancing the model’s ability to discern true community structures, particularly in networks where node degree is not uniformly distributed.

Model selection in community detection utilizes the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to optimize the balance between model complexity and its ability to fit the observed network data, thereby mitigating the risk of overfitting and generating inaccurate community assignments. Evaluations of community detection algorithms reveal a high degree of consensus when applied to inventor networks, as evidenced by Rand Index scores consistently exceeding 0.93; however, agreement is substantially lower for organization networks, with Jaccard Index scores ranging from 0.29 to 0.54, suggesting greater structural ambiguity or differing interpretations of community boundaries in these contexts.

The Broader Implications for an Equitable Innovation Landscape

Innovation networks, while often lauded for fostering progress, frequently organize into densely connected, yet isolated, communities. These tightly knit groups, though efficient at internal knowledge sharing, can inadvertently create significant barriers to entry for external actors seeking to contribute or benefit from new ideas. Research indicates that information and resources tend to flow more readily within these established clusters, effectively limiting access for organizations or individuals operating on the periphery. This structural characteristic isn’t necessarily intentional, but the result is a fragmented landscape where valuable knowledge remains siloed, hindering broader innovation and potentially reinforcing existing inequalities. Consequently, understanding the boundaries and connections within these communities is essential for designing strategies that promote more inclusive and accessible innovation ecosystems.

Innovation networks, while often touted for their collaborative potential, frequently exhibit pronounced hierarchical structures that concentrate both influence and resources among a select few organizations. Research indicates that this disparity is particularly acute within artificial intelligence networks, where a small number of entities consistently dominate knowledge production, funding acquisition, and overall network centrality. This concentration isn’t merely a matter of natural competition; it actively reinforces existing inequalities, creating significant barriers to entry for smaller organizations and potentially stifling diverse perspectives. The resulting power imbalance can limit the overall pace of innovation and hinder the development of AI solutions that address a broader range of societal needs, effectively creating an innovation ecosystem where benefits accrue disproportionately to those already at the top.

A thorough comprehension of innovation network structures – specifically, how tightly knit communities and hierarchical arrangements impact knowledge flow – is paramount for crafting effective policies and interventions. Recognizing that current ecosystems can inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities allows for the targeted design of mechanisms promoting broader participation. These interventions might include incentivizing collaboration between core and peripheral organizations, funding programs that specifically support underrepresented innovators, or establishing open-access platforms for knowledge sharing. Ultimately, addressing these structural characteristics isn’t simply about fairness; it’s about unlocking the full potential of innovation by ensuring that diverse perspectives and talents contribute to the development of new technologies and solutions, fostering a more robust and equitable innovation landscape for all.

The study of innovation networks reveals patterns mirroring the inevitable entropy of all complex systems. This research, detailing cohesive teams and hierarchical organizations, observes that the flow of knowledge-or its restriction-directly impacts technological progress and the distribution of its benefits. As Albert Einstein observed, “The only source of knowledge is experience.” This holds true for innovation; networks are not static blueprints but rather accumulated experiences of collaboration and competition. Delaying the integration of new knowledge, or failing to foster collaborative environments, acts as a tax on ambition, hindering the graceful aging of the system and potentially accelerating its decay. The identified mesoscale structure isn’t merely a snapshot, but a record in the annals of technological development.

The Long View

The revealed duality of innovation networks – cohesive teams nested within hierarchical structures – does not represent a final state, but rather a snapshot of ongoing decay and adaptation. The system will not strive for optimization, only for continued existence. The observed interplay between collaboration and inequality suggests that increased connectivity does not necessarily equate to equitable knowledge diffusion; it merely shifts the points of systemic stress. Future work must address the temporal dynamics of these networks, acknowledging that every connection forged is also a potential point of failure, every successful team a precursor to eventual fragmentation.

Current metrics of “impact” remain stubbornly static, treating technological advancement as a linear progression rather than a complex, oscillating system. A more nuanced understanding requires quantifying not simply what is innovated, but the rate of systemic error correction. The research hints at diminishing returns on increased collaboration; further investigation should explore the conditions under which redundancy becomes detrimental, and how networks can be designed to gracefully accommodate inevitable decline.

Ultimately, the study of innovation networks is not about discovering ‘best practices’, but about mapping the topography of systemic aging. The networks examined are not striving for perfection, merely for continued operation within constraints. The challenge lies in accepting that incidents are not anomalies, but intrinsic steps toward maturity, and that the most robust systems are those that anticipate – and even welcome – their own eventual obsolescence.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10224.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

2026-01-18 14:54