1

1

As a film enthusiast who has been fortunate enough to witness a plethora of cinematic masterpieces, I must say that “Nickel Boys” stands out as one of the most impactful and immersive films I’ve ever seen. The story, inspired by true events, is heart-wrenching, but it’s the unique narrative approach that sets this film apart.

“The essence of cinema lies in its ability to make us feel as if we’re walking a mile in someone else’s shoes. Now, imagine a film that takes this one step further, enabling us not just to see the world through another person’s eyes but also to perceive how others view the individual whose perspective we’ve adopted. This level of intimacy might foster greater understanding and empathy.

In a first-person narrative style, filmmaker RaMell Ross‘ “The Nickel Boys” is a personally immersive and innovative retelling of Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel from 2019.

The tragic experiences at Florida’s Dozier School for Boys served as the basis for Whitehead’s work. Established in 1900, this institution was shut down in 2011 following an investigation that uncovered numerous instances of abuse, deaths, and undisclosed graves.

Ross’s creative interpretation of the book features interspersed archival images and documents regarding Dozier, yet its main focus lies in the immersive, sensory experiences of Elwood (Ethan Herisse), a thoughtful Black teenager growing up in 1960s Tallahassee with his grandmother Hattie (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor). Elwood’s friendship with Turner (Brandon Wilson), who he meets following an unjust arrest at Nickel Academy, which serves as a substitute for Dozier, is also central to the narrative.

Experiencing “Nickel Boys” involves immersing yourself in its “conscious viewpoint,” as Ross labels the film’s cinematography. This implies recognizing both the kindness and severity of the world that Elwood and later Turner face – not just as an observer, but as if we are experiencing it firsthand ourselves. Furthermore, when other characters gaze straight into the camera to speak to Elwood or Turner, they seem to be looking at us through the screen.

The innovative storytelling approach displayed in “Nickel Boys” by director Barry Jenkins and cinematographer Jomo Fray has gained recognition through awards from critics’ groups and surprised audiences. Notably, this is Jenkins’ first venture into scripted fiction after his Oscar-nominated documentary “Hale County This Morning, This Evening,” which captures moments of contemporary Black life in Alabama.

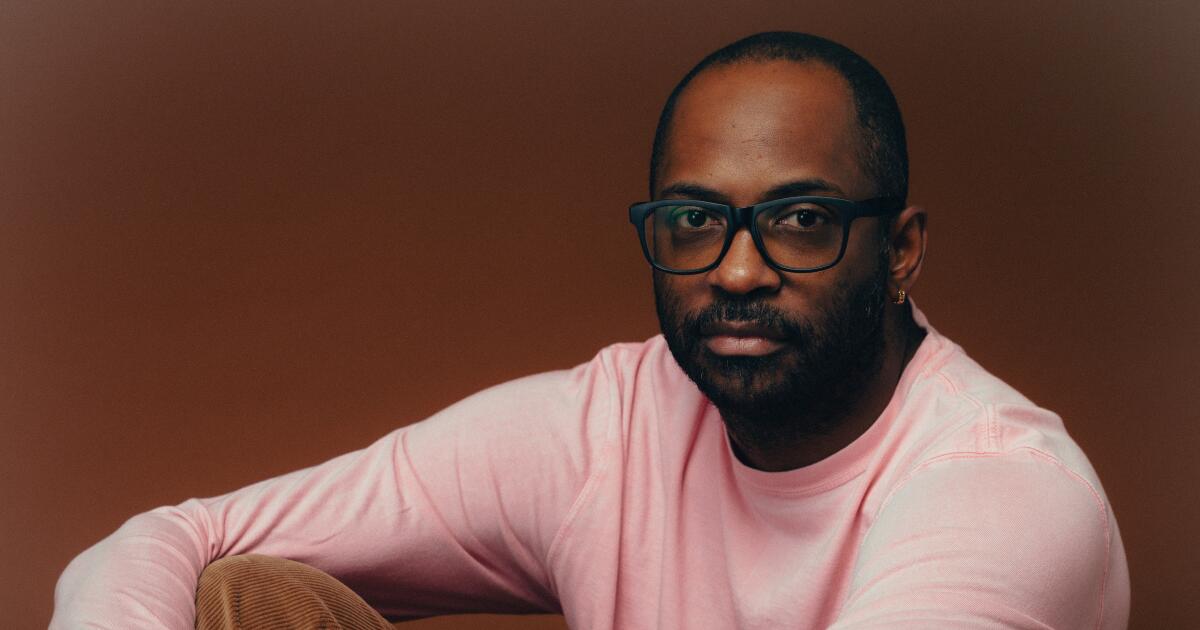

Ross, aged 42, explains to me that he never doubted its success, “I simply assumed it would work.” He adds that what’s lacking in humans’ ability for empathy is the simultaneous sharing of experiences with others. This concept is foundational to his idea.

In a posture that was simultaneously tensed yet relaxed, the director balanced his hands behind his head while crossing one leg over the other. Just like in “Nickel Boys,” this production demanded an intricate blend of precise craftsmanship to create an impression of effortless poetic beauty.

Movies

Following a Labor Day weekend in the Colorado Rockies, where we enjoyed watching movies, our departure from Telluride brings us several notable highlights: striking documentaries and adventurous storylines.

Initially, Ross teamed up with Joslyn Barnes, who was both a screenplay collaborator and a producer for the movie as well as “Hale County”, to draft the script. They obtained an early manuscript of Whitehead’s book from production houses Plan B and Anonymous Content prior to its publication in 2019.

From the start, the writing team decided to capture the core of the novel, without using any images directly from it, primarily for reasons of respect and self-preservation. To prevent judgments based on what was included versus what wasn’t, Ross chose to refract the fictional characters’ lives through his own unique perspective.

He mentions one advantage of him directing the film is that he identifies with Elwood and Turner since he’s a Black child himself. By reflecting on his own life, observations, and experiences, he can seamlessly integrate them into their storyline. This sense of authenticity arises because it truly reflects his reality.

In Ross’ perspective, “Hale County” functioned significantly as a visual and philosophical foundation for “Nickel Boys.” He imagined Elwood and Turner having their own cameras, capturing their unique perspectives of “Hale County.” Essentially, they were creating their individual versions of the documentary. So, if these characters were to photograph “Hale County,” what aspects would they highlight? This approach suggested that the narrative was more about visual imagery than linguistic expression.

According to Ross, we had to deeply understand their perspective and make the camera a part of their being, so we sought to learn what catches their attention, how they create meaning from their surroundings, and ultimately, how this reveals their true identity.

During the process of creating this project, Ross and Barnes recognized that the movie was being manufactured by large corporations instead of independently. Although they were determined to present it in a first-person style, they had some doubts about whether the emotional impact of such a dramatic piece would connect with audiences.

In this movie, according to Barnes during our conversation, you’ll likely find yourself sitting right on the edge, actively engaged and involved, rather than casually watching from afar.

In “The Nickel Boys,” the theme of “the transfer of love” as expressed by Barnes, is central. Hattie’s affection for Elwood exposes him to the empathetic teachings of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., fostering in him a broader understanding of political activism. Later, Hattie embraces the more skeptical Turner, paving the way for a brotherly bond between them and Elwood. This friendship proves to be a significant turning point.

Additionally, Ross highlights another instance where Ellis-Taylor seems to address us, the audience, much like how she gazes affectionately at her grandchild. This subtle yet powerful scene in the movie serves as a significant emotional anchor.

Typically, her gaze towards her grandson would convey to us that she’s filled with love, but we simply observe this – we don’t personally feel it, according to Ross. He hasn’t witnessed anyone else project such intense love through a camera lens directly into the hearts of the audience.

Due to the perspective through which we view events being that of a Black teenager in the Jim Crow South, the gaze returned by others frequently carries an air of racist prejudice, as Barnes describes. This is evident early on when a white policeman scrutinizes young Elwood merely for happening to cross his path.

In Ross’ words, “First-person view (POV) techniques like ‘Hardcore Henry’ have been around for a while, but they don’t typically occur within the context or the narrative of someone else’s life, and more specifically, not during their race or competition.

Viewers who don’t share similar racial backgrounds with Elwood might find it intriguing, possibly accompanied by a feeling of camaraderie – but for those deeply acquainted with Elwood’s real-life journey, watching “The Nickel Boys” could stir up complex feelings.

In simpler terms, Ross thinks that when a Black individual (or anyone from a diverse background) watches this movie, as it offers an insight into another Black person’s perspective, it could potentially intensify their personal experiences.

According to Ross, it’s like saying, “At last, I see myself reflected in such an intimate manner, from within,” but there’s also a sense of being nearly overwhelmed or re-traumatized. With this understanding, Barnes and Ross intentionally chose not to portray any physical violence on screen.

Awards

Co-writer Joslyn Barnes notes that the journey of love between characters was a continuous theme running throughout the movie.

Speaking over Zoom from New York, cinematographer Fray expressed excitement about challenging the traditional barrier between viewers and stories on-screen. This boundary, as he refers to it, often hinders a viewer’s ability to fully immerse themselves in the visual experience. The film “Nickel Boys” disrupts this norm.

The producers proposed Fray as a potential partner for Ross. At their initial encounter, Fray expressed his ambition to create a film that mirrors Ross’s acclaimed large-format photography style. This selfless remark impressed the director greatly.

According to Fray, RaMell’s goal was to create an engaging environment. He wanted the audience not just to understand the harshness of the Jim Crow South, but also to empathize with the experience of Black youth, to sense what it’s like to navigate the world from their perspective.

As a cinephile, I found myself delving into some fascinating film discussions with Ross and Fray. We touched upon Terrence Malick’s visually stunning masterwork, “The Tree of Life,” and the challenging, epic Russian sci-fi production, “Hard to Be a God.

The result was a rigorous shot list of intentionally designed maneuvers — “maybe 35 or 36 pages, single-spaced,” Fray recalls, “meticulously describing every single pan, tilt, gesture or move with the camera.”

In each scene, a single, extended shot without any cuts or edits was employed, often referred to as a long take or “oner.” The methods used to achieve this differed, primarily involving actor Fray, director Ross, and camera operator Sam Ellison navigating the various locations.

According to Fray, there’s a significant difference between using a camera attached to his shoulder versus holding it in his hands. He describes the handheld approach as feeling more like a head on a neck due to its mobility and quick adjustment capabilities. This level of flexibility can’t be achieved physically when the camera is mounted on his shoulder.

The performers, be it Herisse or Wilson, would position themselves near the cameraperson, not just for dialogue delivery, but also to ensure that their hand actions and interactions with fellow actors or props were visible within the camera’s frame.

At times, the two main characters donned specially designed harnesses connecting cameras to their bodies, creating an intensely immersive visual impact. In other instances, the filmmakers employed a SnorriCam – a unique camera tool – mounted on the back of the older Elwood (Daveed Diggs) to depict the disconnected, detached feeling that trauma can cause in its victims, from their perspective.

The person behind the camera seemed to become either Elwood or Turner, as Fray explained. “As a cinematographer,” he said, “this shift in position fundamentally altered my relationship with photography. When the camera embraces a character, it’s like they are embracing me, and that closeness is palpable.

One occasion that demonstrated to Fray the truly transformative potential of this storytelling method was through Ellis-Taylor’s case.

In Fray’s recollection, Aunjanue deviated from the script. She gently touched the table and said, “Elwood, look at me, son.” At that moment, I transitioned from being a camera operator and cinematographer to becoming her scene partner. She relied on me, as Elwood, to comprehend her words, so my camera subtly moved upward and reestablished visual contact with Aunjanue.

Since its premiere at the Telluride Film Festival, “Nickel Boys” has inspired passionate reactions.

Ross mentions that he’s not sure if it’s the style of the movie, whether it’s point-of-view shots, specific visuals or audible elements, but suggests it might be a mix of all these factors. However, after watching, no one has ever expressed a similar interpretation. Instead, it consistently triggers a personal, subjective reaction.

Despite its bold formality, “Nickel Boys” carries a profoundly human spirit. It’s my hope that when the lens stops blinking, viewers will feel as if they understand these characters more intimately than they could ever imagine understanding anyone else.

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Country star who vanished from the spotlight 25 years ago resurfaces with viral Jessie James Decker duet

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- Solo Leveling Season 3 release date and details: “It may continue or it may not. Personally, I really hope that it does.”

- Kingdoms of Desire turns the Three Kingdoms era into an idle RPG power fantasy, now globally available

- JJK’s Worst Character Already Created 2026’s Most Viral Anime Moment, & McDonald’s Is Cashing In

2024-12-20 02:02