In 1977, while at a crowded movie theater, Michelle Phillips suddenly recognized someone – her marijuana supplier! Just months before, she’d known him as a carpenter who also smoked pot and had only appeared in small roles. Now, he was Harrison Ford, starring as Han Solo in the new film “Star Wars,” directed by a relatively unknown George Lucas. It was a clear sign that things were rapidly changing.

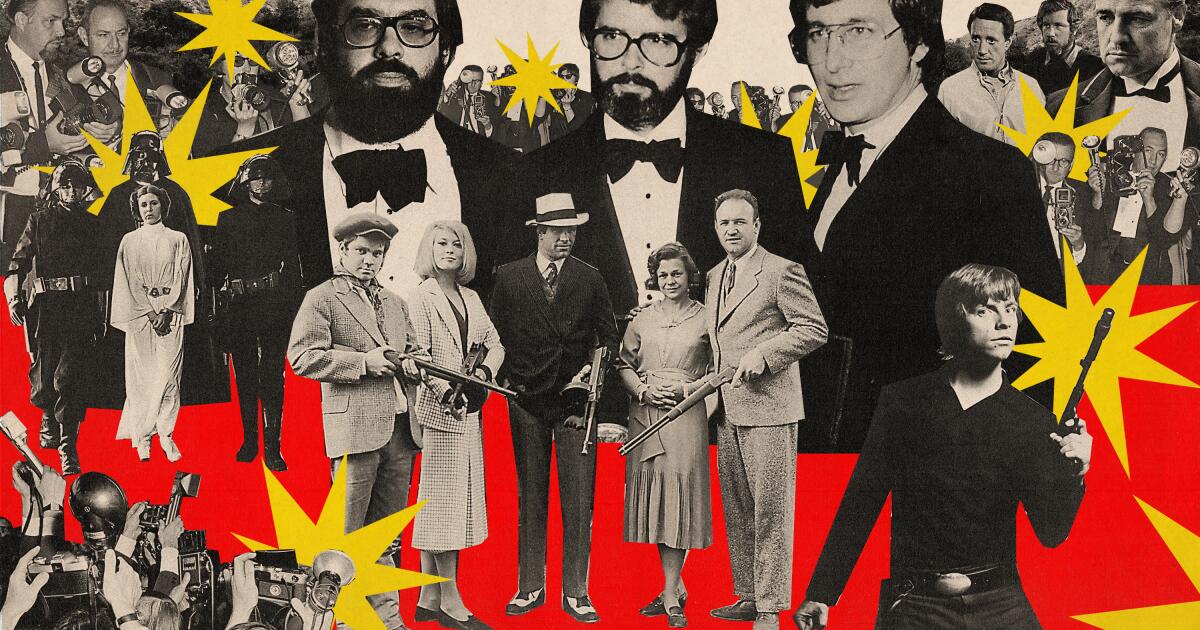

But how significant was this change, really? The commonly held belief is that the Hollywood films of the 1960s and 70s were revitalized by a new wave of directors. Films like “Bonnie and Clyde” and “Easy Rider” are often credited with shaking up the studio system and fundamentally changing American cinema. And there’s a lot of validity to that idea. For example, Francis Ford Coppola went from directing standard musicals like “Finian’s Rainbow” to creating a masterpiece like “Apocalypse Now” within just ten years – a truly impressive feat of that era.

However, two recent books indicate that the changes weren’t as significant as believed. They actually reinforced the traditional studio system and the existing social expectations that newcomers were trying to challenge.

Paul Fischer’s engaging book, “The Last Kings of Hollywood,” focuses on the careers of George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg – the groundbreaking directors who emerged from California. While filmmakers like Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma are mentioned, the book primarily centers on these three. Fischer excels at showing how many iconic moments in film history weren’t planned, but rather happened through a combination of chance, difficult compromises, and risky choices. For example, Coppola only made “The Godfather” because he needed a hit, and was initially reluctant to adapt a gangster story. Spielberg’s “Jaws” faced numerous problems during production, including failed attempts to use a live shark. And Lucas only started developing his own space epic after discovering he couldn’t secure the rights to “Flash Gordon.”

The energy and ambition of this filmmaking group was truly exciting. They created huge hits like “The Godfather,” “American Graffiti,” and “Jaws,” leading many to believe that big-budget movies didn’t need to be controlled by traditional studios. George Lucas, especially, was motivated as much by a desire to prove the old guard wrong as by his passion for new ideas. He hadn’t forgotten how Warner Bros. had treated his first film, “THX 1138,” and was determined to make “American Graffiti” despite those who doubted him. In 1969, Coppola and Lucas even started their own studio, American Zoetrope, in San Francisco, with several projects in development – including “Apocalypse Now” and “The Conversation” – and a $300,000 investment from Warner Bros. However, Coppola wasn’t a natural businessman, and found it easier to enjoy the studio’s espresso machine than to manage the advanced editing facilities. As one writer put it, he ran the business based on instinct and feeling, much like a film set.

Movies

The 101 best Los Angeles movies, ranked

We’ve compiled a list of 101 fantastic movies set in Los Angeles, reflecting the city’s vastness and diversity. It includes classics like “Chinatown,” popular favorites like “Clueless,” and modern hits like “La La Land,” as well as films like “Blade Runner,” “Mulholland Drive,” “Heat,” and “Pulp Fiction.”

Looking back, it’s a bit tragic. Ten years after their ambitious start, both Francis Ford Coppola and Zoetrope Studios ended up bankrupt, and his partnership with George Lucas dissolved. Lucas, riding high on the massive success of “Star Wars,” forged his own empire with Lucasfilm, becoming a powerful producer. He got to play with the kinds of adventure serials he loved, even bringing Spielberg on board for “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” But according to the author, despite all the money, Lucas’s career felt like a letdown. He really wanted to get back to making more artistic films like his early work, “THX,” but needed consistent hits to fund it. He figured abstract, experimental films weren’t the way to true independence. By the eighties, and after a couple of “Star Wars” sequels, Lucas had completely abandoned that artistic ambition, focusing solely on blockbuster entertainment.

Unlike “Last Kings,” which only examines how directors deal with movie budgets, Kirk Ellis’s “They Kill People” offers a broader look at “Bonnie and Clyde” and the New Hollywood era. It considers filmmaking techniques, the social unrest of the 1960s, and America’s complicated views on both outlaws and guns. The book is thorough but easy to read, and it effectively captures the unique circumstances surrounding the film’s creation and the somewhat controversial aspects of its lasting impact.

The film “Bonnie and Clyde” was shockingly violent for its time, so Warner Bros. reluctantly released it. The studio gave it very little money, and Jack Warner, the studio head, openly ridiculed the director, Arthur Penn, and star Warren Beatty, calling them “geniuses” with heavy sarcasm. It was first shown mainly in drive-in theaters in the South, with the assumption that audiences there would appreciate the film’s gun violence, according to Penn.

The film was popular with audiences, though some critics found its violence excessive, particularly the graphic ending. Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway had strong onscreen chemistry and were always impeccably dressed. The film’s rebellious spirit appealed to young people in the late 1960s. According to historian David Ellis, the movie also reflected a long-growing American belief that guns represent freedom – an idea that wouldn’t have resonated with the country’s founders, who didn’t focus much on gun rights in early documents. Ellis points out that the connection between guns and freedom is a relatively recent development, promoted by gun manufacturers and reinforced by films like “Bonnie and Clyde.” It’s a manufactured legend, he argues, not a reflection of America’s original values.

Entertainment & Arts

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will finally open its doors after almost four years of postponements.

Focusing solely on the directors featured in these books would be a mistake. Their emphasis on white men unfortunately reflects the broader pattern of excluding women and people of color, often limiting them to less prominent roles in genres like blaxploitation. However, the 1970s still offer a lot of inspiration for artists wanting to work outside traditional structures. These books also reveal a familiar pattern: the film industry tends to take bold ideas, soften them, and prioritize profit. This became clear in the early 1980s when Paramount’s Michael Eisner bluntly stated the company’s goal: to make money, with no concern for artistic or historical significance.

It wasn’t for another ten years, with filmmakers working on the East Coast, that a new wave of films like “Do the Right Thing” and “sex, lies, and videotape” challenged that style. These films helped start the rise of Miramax, though that’s a complicated story for another time.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

Read More

- CookieRun: Kingdom 5th Anniversary Finale update brings Episode 15, Sugar Swan Cookie, mini-game, Legendary costumes, and more

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- How to get the new MLBB hero Marcel for free in Mobile Legends

- Alan Ritchson’s ‘War Machine’ Netflix Thriller Breaks Military Action Norms

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Robots Learn by Example: Building Skills from Human Feedback

2026-02-20 14:38