As a passionate conservationist and animal lover, I find myself deeply moved by Eric Goode’s story. His dedication to preserving endangered species, particularly turtles and tortoises, is truly commendable. It’s clear that his connection with these animals runs deep, much like the bond between man and beast in my own life.

The director anticipated the person he was filming would feel enraged. There might have been tears or shouts, perhaps even harsh words directed at him. After all, she had been deceived by him.

For two years, Eric Goode, the producer behind the mega-hit “Tiger King,” had purposefully concealed his identity from the star of his new documentary series. Her name was Tonia Haddix, an Ozarks-based exotic animal broker who was obsessed with chimpanzees. And Goode would ultimately play a key role in having the “humanzee” she considered her child, an ape named Tonka, removed from her home.

Initially, when Goode and Haddix eventually had a face-to-face encounter on film, she was gracious. In fact, she was quite amiable. “She was astonishingly accepting of it,” the director, now 66, reminisces, “almost to the point where she felt more significant because it was me.”

Initially, Haddix granted permission for cameras to document her life for an additional year and a half, eventually leading to the four-part docuseries “Chimp Crazy” which debuted on HBO and Max this month. However, following its release, Haddix (who did not respond to queries from The Times) has expressed regret about her decision to participate, stating that she would have declined if she’d known it was a Goode production in advance. The series’ ethics have also been questioned by critics, who are debating the guidelines that should be followed by non-fiction filmmakers, particularly those creating series with significant entertainment value.

Goode clarifies that he doesn’t consider himself a journalist nor an animal rights activist, instead identifying as someone who advocates for animal welfare. Furthermore, he hadn’t been a filmmaker prior to the release of “Tiger King.”

Goode doesn’t strictly adhere to the educational and ethical principles commonly followed by conservationists and journalists. He refers to these guidelines as “indoctrinated boundaries.” By doing so, he has more leeway to discover or even create intense conflicts on screen, which traditional documentarians might avoid. However, Goode’s unease about his actions against Haddix suggests that this method isn’t without its risks. Although he may not identify as an activist, his filmmaking career began due to a passion for protecting exotic animals. Those watching “Chimp Crazy” or “Tiger King” without knowing this background might feel confused.

The seven-episode series “Tiger King,” debuting on Netflix in March 2020 amidst nationwide lockdowns due to COVID-19, showcased the peculiar world of private tiger ownership and achieved unprecedented success during the streaming era. It brought Joe Exotic, a flamboyant convict known for his mullets, tattooed eyeliner, and big cats, into public spotlight. It also catapulted Carole Baskin, Joe’s arch-nemesis, to “Dancing With the Stars.” In 2022, the Big Cat Public Safety Act, a decade-long campaign by animal rights groups, was finally enacted by President Biden, banning private citizens from owning animals like lions, tigers, and leopards.

Goode is not a big-cat aficionado himself, but he’s been drawn to reptiles since he was a boy. Growing up in Sonoma in Northern California, he and his four siblings roamed the family’s land, playing with spiders and snakes. It was the gift he received on his 6th birthday that most captured his attention, though: a Greek tortoise, whose shell would go on to become the logo for the Turtle Conservancy he opened in Ojai in 2005.

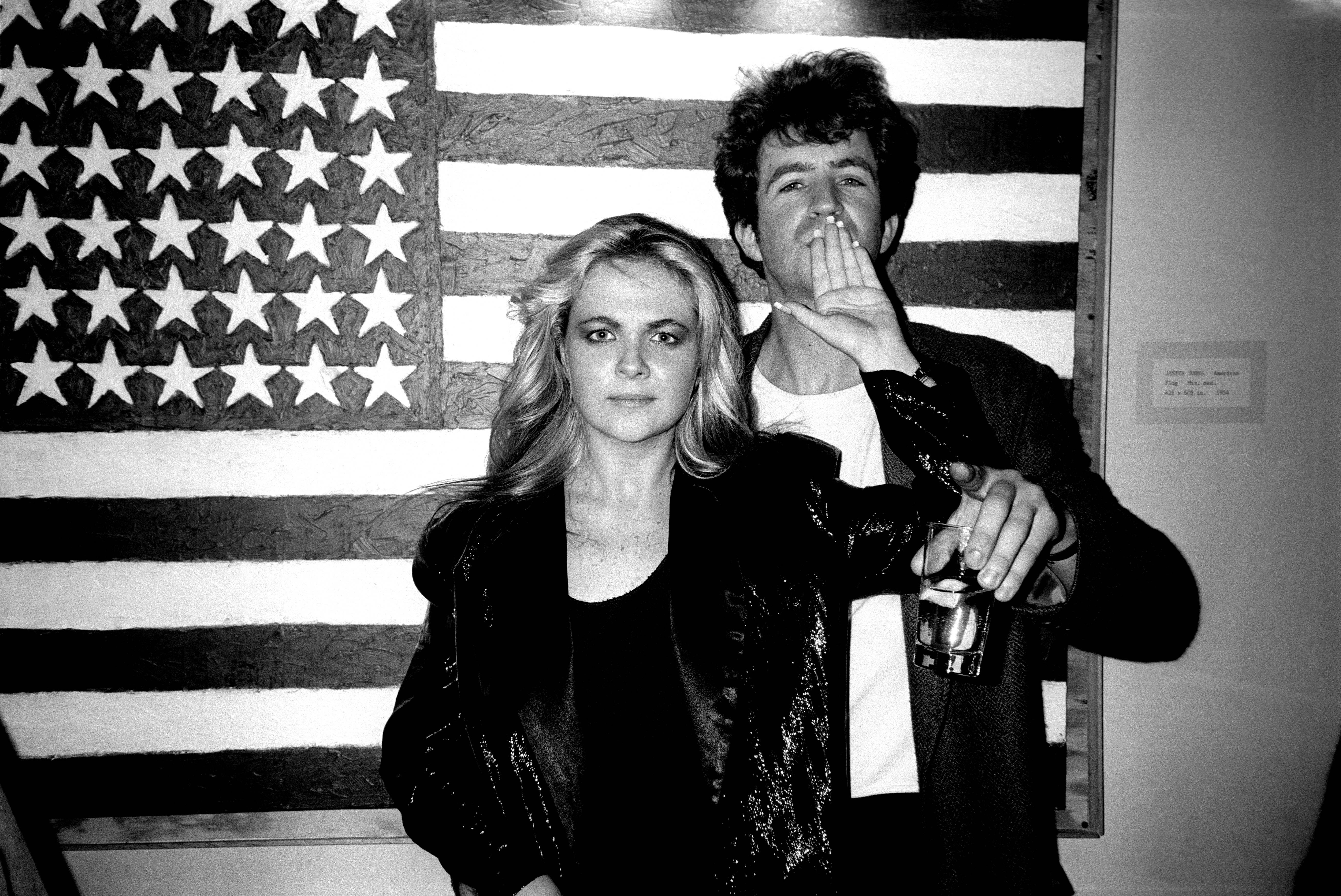

In his twenties, Goode became well-known in New York City’s nightlife scene, jointly establishing Area – a popular 1980s club showcasing art installations by artists such as Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. He later opened venues like the Waverly Inn, the Bowery Hotel, and the Jane Hotel. Goode socialized with Madonna, dated Naomi Campbell, and directed a couple of Nine Inch Nails music videos; one of these videos, titled “Pinion,” was so explicit that MTV refused to air it in its entirety.

During this time period, Maurice Rodrigues, who worked part-time as a zookeeper at the Bronx Zoo, initially met Goode. The incident occurred when Goode’s restaurant, the Park, had a fish tank malfunction and Rodrigues was summoned for repairs. Following the repair, Goode extended an invitation to him for dinner at the same establishment.

In his early 30s, Rodrigues recalls being a small-town Jersey resident, seated at the finest table in the room with real models. However, instead of engaging with these stunning women, he and Eric became engrossed in a conversation about turtles, to the point where they were oblivious to their presence. Eventually, the models grew annoyed and announced they were leaving. With a casual wave, Eric simply replied, “Alright, see you later!”

Sharing a common passion for turtles, terrapins, and tortoises, these two companions embarked on worldwide journeys to study these fascinating reptiles. However, the conferences of the Turtle Survival Alliance they attended lacked excitement, as listening to repetitive lectures based on scientific papers they’d already read felt tedious. A more engaging approach could be showcasing video material instead.

As a cinephile, I’ve shared the mission to purchase animals from poachers and document the process with hidden cameras. We procured covert devices and even glasses equipped with a concealed camera. The risk was palpable; I couldn’t help but think we might be walking into danger.

In 2009, the documentary “The Cove” was released. This film, which exposed a brutal dolphin hunt in Japan, won the best documentary award at the Academy Awards that year. After this success, Eric commented, “Enough with these small-scale films. Let’s create something for a global audience, something we can present to anyone. If it succeeds, perhaps we can use the funds for conservation efforts.”

With his personal funds, Goode embarked on a journey with a compact film crew, intending to create a work centered around the extinction crisis. CNN stumbled upon this footage and agreed to produce a pilot episode for a potential TV series. However, the network declined the show in 2019. Post the success of “Tiger King,” Goode revisited the themes he’d previously explored for his upcoming project.

Jeremy McBride, a partner at Goode, shared that they were examining the context of exotic animal markets in Southeast Asia, focusing on female hunters and butterfly collectors. The aim was to delve into the broader topic of how people interact with unusual creatures from different parts of the world.

At the Missouri Primate Foundation, tensions began escalating. The institution’s proprietor, Connie Casey, was known for breeding chimpanzees that featured in films, adorned Hallmark greeting cards, and entertained at children’s birthday parties. Among these chimps was Travis, whom she sold for $50,000 as an infant. Tragically, this chimp later attacked a woman named Charla Nash in Connecticut in 2009, causing her to lose her eyes, nose, lips, and nine fingers.

Following a dozen citations from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Casey was taken to court by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) in 2017, who alleged that she had breached the Endangered Species Act. It was then that Haddix, wanting to buy a chimpanzee, discovered Casey’s predicament and decided to assume legal responsibility for the animals to aid her friend in avoiding legal issues.

However, PETA persisted in their stance. In 2020, they managed to negotiate a deal with Haddix which allowed her to retain some chimpanzees on her Missouri estate, under the condition that she would upgrade and expand their living quarters.

In the heat of these ongoing legal exchanges, it was during the month of June 2021 that Haddix got a call from Dwayne Cunningham on his phone.

In a unique move, Goode enlisted the help of a former circus clown from Barnum & Bailey, who served a 14-month sentence in federal prison back in 1999 for trading endangered tortoises and iguanas, to act as his intermediary with Casey. Casey, who has refrained from granting interviews since Peter Laufer’s 2010 book “Forbidden Creatures”, might be more inclined to speak with someone whose livelihood was similarly affected by animal rights activists, rather than the person behind the documentary “Tiger King”.

Cunningham welcomed the task since, being an animal enthusiast, he yearned to personally verify if the chimps were indeed suffering mistreatment. Similarly, Goode remained haunted by Laufer’s account – a friend and fellow advisory board member at his Turtle Conservancy – about his Missouri experience.

According to Goode, Peter found it incredibly gruesome – even more so than his prison interviews or civil war experiences. Nothing could have prepared him for it, says Goode. However, the understanding of what was happening within that house made him believe that it was justified, both morally and ethically, in his mind. He thought to himself, ‘Under the circumstances, the end justifies the means.’

The plan partially succeeded. While Casey didn’t consent to an interview, Haddix was eventually won over by Cunningham. Later, Haddix shared with Rolling Stone that she joined the project because Cunningham was passionate about animals, often arriving early to help bottle-feed the baby hoofstock.

Using various hairpieces, false eyelashes, and sun-kissed skin, the 54-year-old woman presented an engaging and thought-provoking figure to observe. Moreover, she was open about her feelings, confessing on camera that she valued Tonka more than her own biological son.

In just a few short days following the arrival of the movie team in Missouri, a judge made a decision: the seven chimpanzees residing there were to be relocated to an ape sanctuary in Florida. This was due to the fact that Haddix failed to meet the renovation standards for the habitat as previously arranged with PETA.

However, when law enforcement officers (local sheriff’s deputies and the U.S. Marshals Service) went to the Missouri property on July 28, 2021, to seize the seven chimpanzees, they discovered that there were only six animals present. Haddix informed them that the missing chimp, Tonka, had passed away from heart failure on May 30.

It turns out that, as “Chimp Crazy” uncovers, Haddix secretly took her cherished chimp to a friend’s place in Ohio. Later, she transferred Tonka to live near the Lake of the Ozarks, where she had prepared her basement with a cage for him.

Shortly following Tonka’s abduction, Haddix revealed her secret to the documentary team. Yet, she was unaware that Goode was involved in the project, a fact he admitted made him uneasy. “I don’t want to be that kind of person,” he confesses. “I kept wondering, ‘When should I tell her it’s me?’ I felt it could have been disclosed earlier.”

While the crew was increasingly uneasy, Haddix found himself in the dark and unknowingly involved in a crime. Alan Cumming, known for his role opposite Tonka in the 1997 film “Buddy,” collaborated with PETA to offer a $20,000 reward for information regarding the chimp’s location. In the series, Cunningham – often called the “proxy director” – admitted that he and some camera crew members brought these concerns to their superiors.

Goodie expresses that it was likely challenging for the team to accept the possibility that there might be a higher purpose in not taking immediate action, he adds. It was a turbulent time, and his thoughts were along the lines of, “If I don’t intervene, will this monkey be alright?” as he discussed with his primatologist peers.

Goode watched a video of Tonka in the basement that scientists were trying to diagnose signs of mental stress from. Meanwhile, Cunningham offered his personal insights about Tonka to Goode: Tonka appeared clean and didn’t show any signs of anxiety. Despite occasional meals like Happy Meals or Powerade given by Tonia, “he was always cared for,” Cunningham notes.

In May 2022, Haddix shared with Cunningham her intention to put down the chimpanzee, explaining that the veterinarian had informed her that Tonka’s health was so poor it would be inhumane to keep him alive. Upon learning this, Cunningham contacted Goode, who then decided it was appropriate to inform PETA about Tonka’s location.

On May 30, 2022, the producers reached out to PETA and asked for a face-to-face meeting. The following day, they sat down with PETA’s legal team. Then, on June 1, PETA submitted an urgent petition to have Tonka taken away from Haddix’s custody.

As a compassionate supporter, I can only imagine how eager I was to learn the instant the filmmakers discovered Tonka was hidden in Tonia’s basement. I am profoundly grateful that they eventually chose to involve us, allowing us to rescue Tonka. Not every documentary filmmaker might have made the same decision, choosing instead to protect their project. However, these filmmakers put a life above their work, and for that, I am truly thankful.

As the countdown to June 5, 2022, when Tonka was taken away, ticked by, I was still clueless about who had spilled my secret. I shared this with Cunningham, who, unbeknownst to me, had a hidden camera on him during our conversations in those days.

“Cunningham firmly states he never felt remorseful. He had always advised Tonia to only share things she wouldn’t mind broadcasting publicly. Given Tonia’s nature, she continued confiding in him. As a result, he didn’t feel guilty; instead, he believed he was fulfilling his duty. However, he did feel sorry for a friend because it was evident that their love story was becoming unmanageable.”

When he finally encountered Haddix, Goode initially shared with her that he empathized with her. As stated in the series, “There are specific creatures,” he explains, “that if they were taken from me, I would feel extremely distressed.”

He was referring to the chelonians he keeps on his Ojai property, where approximately 40 endangered species of turtles or tortoises live. While he says he does like being around them for “selfish reasons,” the animals reside in Southern California because they’re either extinct in the wild or so endangered that poachers pose a critical risk to the remaining population. “I don’t want to say I’m, like, trying to create a loophole for why I can keep a tortoise and someone can’t keep a chimp,” he says. “It would certainly be better to keep our animals in the wild, just because the environmental conditions are very hard to replicate.”

Jane Goodall has been a subject of debate within conservation communities. Craig Stanford, an anthropologist specializing in human evolution who oversees USC’s Jane Goodall Research Center, often faces skepticism from his peers regarding his association with someone who was involved in a project considered as questionable as the Netflix series “Tiger King.” (He serves on the Turtle Conservancy’s Board of Directors and participated in an interview for “Tiger King” that ultimately didn’t make the final cut.)

As a passionate movie enthusiast, I find myself defending my peers when they criticize one another for using stunning yet endangered creatures as a means to amass wealth. Instead of just pointing fingers, I choose to acknowledge their actions and highlight the positive outcomes that have resulted. Yes, it’s true that profits were made, but let me remind you, this individual brought attention to these magnificent animals, which ultimately led to stricter regulations being implemented.

In my perspective, having these judgments stirs a longing within me for one of my other projects, those not centered around animals, such as the documentary I recently completed about my late mother, to be released prior to “Chimp Crazy.” This way, the audience wouldn’t misconstrue that I’m limited to this ‘Tiger King’-style model and believe that’s all I’m capable of.

According to him, Haddix has been finding it tough since the release of the film. A short while ago, Cunningham went to St. Louis to show her all four episodes. After she saw the first one, which contains the most footage of her with Tonka, he claims she cried in his embrace. Then there was a moment of quietness. “I had to tell her it was time to get off the couch so we could move it back,” Cunningham recounts. “This made her laugh, and that helped lighten the mood a bit.”

Haddix and Goode have been consistently sending text messages back and forth. The director mentions that Haddix asked for multiple “Chimp Crazy” posters to be delivered so she could sign and sell them. In public, though, Haddix appears to be telling a different tale, which displeases Goode.

He states that it was never true that he had given her money to keep filming with him, nor had he promised access to Tonka. He clarifies this point and adds that while they did work together, the production did compensate her for using some old footage of hers.

According to Goode’s perspective, Haddix would have ultimately been discovered, whether he was involved or not. She herself confided to friends, relatives, and neighbors that Tonka was hiding in her basement.

“Indeed, we’re the ones who handed her over, but I believe it was unavoidable,” he explains. “I strive to follow the ethical guidance my mother instilled in me throughout my life. I may not always understand where it places me, but there’s definitely a moral compass at play.”

Read More

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

2024-08-25 13:32