Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are exploring how large language models can give drones the reasoning skills needed to navigate complex indoor environments without pre-mapping.

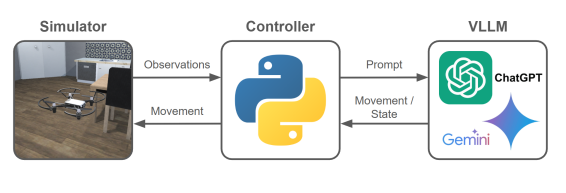

This work presents VLN-Pilot, a system leveraging large vision-language models and a finite state machine for robust and interpretable indoor drone navigation with sim-to-real transfer.

Achieving truly autonomous indoor drone navigation remains challenging due to the complexities of dynamic environments and the need for robust, high-level reasoning. This paper introduces VLN-Pilot: Large Vision-Language Model as an Autonomous Indoor Drone Operator, a novel framework leveraging large vision-language models (VLLMs) to interpret natural language instructions and execute drone trajectories in GPS-denied spaces. By integrating language-driven semantic understanding with visual perception, VLN-Pilot demonstrates high success rates on complex, long-horizon navigation tasks within a photorealistic simulation. Could this approach pave the way for scalable, human-friendly control of indoor UAVs in applications ranging from inspection to search-and-rescue?

The Challenge of Indoor Autonomy: Beyond Simple Flight

Successfully piloting a drone through indoor spaces presents a formidable engineering challenge, demanding far more than simply scaling down outdoor GPS-reliant systems. The unpredictable nature of interiors – cluttered layouts, constantly changing lighting, and the absence of clear aerial pathways – necessitates a drone’s ability to perceive its surroundings with exceptional detail and make instantaneous, informed decisions. Robust perception isn’t merely about ‘seeing’ obstacles; it requires interpreting the meaning of those obstacles – is it a permanent fixture, a temporary object, or a traversable space? This, coupled with the need for real-time path planning and agile maneuvering, pushes the boundaries of onboard processing power, sensor technology, and algorithmic sophistication, making truly autonomous indoor navigation a pivotal area of ongoing research and development.

Conventional drone navigation techniques, reliant on pre-mapped environments or highly structured sensor data, often falter within the unpredictable realities of indoor spaces. Unlike the open skies where GPS signals provide consistent positioning, interiors present a chaotic mix of moving objects, variable lighting, and a lack of clear geometric features. These dynamic conditions overwhelm algorithms designed for static environments, leading to inaccuracies in localization and mapping. Consequently, drones employing these traditional methods experience difficulty adapting to unexpected obstacles or changes in layout, severely limiting their ability to operate reliably and autonomously within homes, offices, or warehouses. The inherent complexity of these spaces demands a shift towards more adaptable and intelligent navigation systems.

The pursuit of truly autonomous drones indoors is increasingly focused on Vision-and-Language Navigation (VLN), a system allowing drones to interpret and execute commands expressed in natural language – envision a drone responding to “fly to the conference room and then circle the large table.” However, realizing this capability demands more than simply combining visual data with language processing; it necessitates the development of a sophisticated “AI pilot.” This pilot must not only understand the semantic meaning of instructions but also correlate them with the visual environment, plan a feasible trajectory, and dynamically adjust to unforeseen obstacles or changes. Current research centers on training these AI pilots using large datasets of paired visual scenes and natural language directions, employing techniques like reinforcement learning to refine their decision-making processes and improve navigational accuracy in complex, real-world indoor settings.

Leveraging Large Vision-Language Models for Autonomous Control

Large Vision-Language Models (VLLMs), including architectures like GPT and Gemini, are increasingly utilized for autonomous drone control by processing visual data from onboard cameras and correlating it with natural language instructions. This integration allows drones to interpret commands such as “navigate to the red container” or “inspect the damage on the north wall” and execute them without pre-programmed trajectories. The VLLM functions as the central processing unit, converting visual input into actionable commands for the drone’s flight controller and manipulating actuators to achieve the desired outcome. This approach contrasts with traditional drone autonomy which relies heavily on pre-defined environments and explicitly coded behaviors, offering greater flexibility and adaptability to novel situations.

Large Vision-Language Models (VLLMs) integrate computer vision and natural language processing to allow drones to interpret both visual data from onboard cameras and textual or spoken commands. This capability extends beyond simple object recognition; VLLMs can process complex instructions containing relational information, spatial reasoning, and conditional logic. For example, a drone might be instructed to “follow the red car until it stops at the intersection,” requiring the VLLM to identify the correct vehicle, track its movement, and recognize the completion condition. The combined visual and linguistic understanding enables drones to autonomously perform tasks based on nuanced and context-dependent directions, moving beyond pre-programmed behaviors.

Effective training and evaluation of Large Vision-Language Models (VLLMs) necessitate a high-fidelity simulation environment due to the impracticality and cost of real-world data collection at scale. Our approach utilizes a Unity-based platform, chosen for its physics engine, rendering capabilities, and scalability. Integration with the ML-Agents toolkit provides a standardized interface for defining agents, actions, rewards, and observation spaces within the simulated environment. This allows for programmatic control over training scenarios, automated data generation, and systematic performance evaluation of VLLMs across a diverse range of tasks and conditions, facilitating iterative model improvement and robust generalization capabilities.

![The drone controller operates via a finite state machine, transitioning between execution states [latex]\mathbf{s}[/latex] based on conditions evaluated through a visual language model (VLLM).](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.05552v1/images/states.jpg)

Structuring Drone Behavior: The Logic of Finite State Machines

The drone’s operational structure is formalized through the implementation of a Finite State Machine (FSM). This FSM dictates the drone’s behavior by defining a discrete sequence of semantic states, transitioning between them based on sensor input and task completion. Example states include Room Recognition, where the drone identifies and maps its current location; Door Navigation, which governs the process of locating and passing through doorways; and Object Search, dedicated to identifying specific items within the environment. The defined states and their associated transitions create a predictable and manageable control flow, allowing for systematic environmental interaction and task execution.

Within the drone’s operational framework, each state within the Finite State Machine (FSM) corresponds to a defined navigational task, such as maintaining a specific altitude, executing a waypoint turn, or performing an obstacle avoidance maneuver. This state-based approach allows for systematic environmental exploration by sequentially executing these tasks. Interactions with the environment, including sensor data acquisition and motor control commands, are encapsulated within each state, ensuring a predictable and controlled response to external stimuli. The drone progresses through these states based on pre-defined conditions and sensor input, facilitating a structured and reliable method for navigating and interacting with its surroundings.

Decomposing complex drone operations into a series of discrete, manageable steps via a Finite State Machine (FSM) directly enhances system robustness and reliability. By limiting the scope of any single operational phase, the potential for cascading failures due to unforeseen circumstances is reduced. Error handling and recovery mechanisms can be implemented within each state, allowing the drone to respond to issues without compromising the overall mission. This modularity also simplifies testing and debugging, as individual states can be validated independently before integration. Furthermore, the defined transitions between states provide a predictable system behavior, facilitating consistent performance across varying environmental conditions and reducing the likelihood of unpredictable actions.

The Expanding Horizon of Vision-Language Navigation

The pursuit of robust Vision-Language Navigation (VLN) is increasingly reliant on transformer-based architectures designed to enhance an agent’s ability to reason over extended sequences and interpret complex environments. Models like the Episodic Transformer (E.T.) and Scene-Object-Aware Transformers (SOAT) move beyond simple instruction following by incorporating mechanisms for retaining long-range dependencies and explicitly recognizing salient objects within a scene. This allows the agent to build a more comprehensive understanding of its surroundings and the navigational path required to reach a designated goal. By attending to both visual cues and linguistic instructions over extended horizons, these architectures demonstrate improved performance in tasks requiring intricate route planning and contextual awareness, effectively addressing the challenges of navigating previously unseen and complex indoor spaces.

Recent progress in visual language navigation (VLN) increasingly relies on sophisticated techniques to overcome challenges in complex environments. Methods like VLN-R1 employ reinforcement learning to optimize navigation policies, while Airbert utilizes pre-training strategies and contextual embeddings for improved instruction following. FlexVLN introduces a hierarchical reasoning approach, breaking down long navigational paths into manageable sub-goals. Furthermore, UAV-VLN specifically addresses the nuances of drone-based navigation, incorporating domain adaptation techniques to bridge the gap between simulated and real-world environments. Collectively, these advancements demonstrate a shift towards more robust and adaptable VLN systems capable of navigating increasingly complex and dynamic spaces.

The progress of Vision-Language Navigation (VLN) is intrinsically linked to the development of challenging datasets designed to mirror real-world complexity. Researchers are now evaluating VLN models on benchmarks like AerialVLN, which focuses on drone navigation from aerial viewpoints, and RxR, a dataset emphasizing realistic human-following instructions. Furthermore, LHPR-VLN introduces long-horizon planning requirements, demanding agents navigate extended and intricate environments, while DynamicVLN adds the challenge of navigating scenes with moving objects and pedestrians. These increasingly sophisticated datasets aren’t simply measuring navigational success; they are actively pushing the boundaries of indoor drone autonomy by forcing algorithms to contend with visual ambiguity, incomplete information, and dynamic surroundings – critical factors for real-world deployment and reliable operation in complex, unmapped indoor spaces.

Comparative evaluations reveal that GPT consistently surpassed Gemini in virtual navigation tasks, achieving a greater success rate in reaching designated target locations while simultaneously minimizing collisions. Detailed analysis of the experiments indicates Gemini exhibited a notably higher incidence of collisions with surrounding obstacles and, critically, more frequently failed to complete the navigation within the prescribed step limit. This suggests GPT demonstrates superior path planning and obstacle avoidance capabilities, potentially stemming from differences in the underlying architectures and training methodologies employed for each model, and highlights a crucial performance gap in complex navigational reasoning.

The pursuit of autonomous drone navigation often layers complexity upon complexity. This work, however, elegantly demonstrates a shift towards principled simplicity. It leverages the reasoning capabilities of large vision-language models, but crucially, grounds them within the structure of a finite state machine. As Claude Shannon observed, “The most important thing in communication is to convey the meaning, not the message.” This echoes in the design; the system prioritizes interpretable navigation – understanding how the drone reaches a destination – over merely achieving it. Abstractions age, principles don’t. The finite state machine provides that enduring principle, ensuring robustness and clarity in an otherwise complex domain.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The coupling of large language models with robotic control-here, an indoor drone-feels less like innovation and more like a necessary simplification. For years, the field chased intricacy: bespoke algorithms for every conceivable scenario, hand-engineered feature extractors, and control loops nested within control loops. They called it robustness; it was, more accurately, a frantic attempt to anticipate failure. This work suggests that a sufficiently capable language model, grounded in visual input, can bypass much of that brittle complexity. The lingering question isn’t whether LLMs can navigate, but whether they can do so with a degree of efficiency that justifies their size.

Sim-to-real transfer remains, predictably, a bottleneck. The drone, confronted with the messiness of actual environments, still falters. One suspects the problem isn’t a lack of data, but a fundamental mismatch between the pristine simulations and the inherent ambiguity of the real world. Future efforts might explore methods for the LLM to actively request clarification-to ask, essentially, “What exactly is that oddly shaped object?”-rather than blindly extrapolating from incomplete information.

Ultimately, the true test won’t be flawless navigation, but graceful degradation. A mature system won’t strive for perfection; it will acknowledge uncertainty, signal its limitations, and, when necessary, politely request human assistance. The goal, after all, isn’t to replace the pilot, but to build a co-pilot that is both capable and, crucially, aware of its own fallibility.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05552.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash of Clans Unleash the Duke Community Event for March 2026: Details, How to Progress, Rewards and more

- Jason Statham’s Action Movie Flop Becomes Instant Netflix Hit In The United States

- Kylie Jenner squirms at ‘awkward’ BAFTA host Alan Cummings’ innuendo-packed joke about ‘getting her gums around a Jammie Dodger’ while dishing out ‘very British snacks’

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brawl Stars February 2026 Brawl Talk: 100th Brawler, New Game Modes, Buffies, Trophy System, Skins, and more

- Hailey Bieber talks motherhood, baby Jack, and future kids with Justin Bieber

- eFootball 2026 Jürgen Klopp Manager Guide: Best formations, instructions, and tactics

- MLBB x KOF Encore 2026: List of bingo patterns

- Jujutsu Kaisen Season 3 Episode 8 Release Date, Time, Where to Watch

- How to download and play Overwatch Rush beta

2026-02-08 07:18