Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that our willingness to extend moral consideration to robots is directly linked to how much we perceive them as human, and how our personal values influence our reasoning.

The study demonstrates that anthropomorphism and moral foundations-particularly progressivism-are key determinants in attitudes toward robot abuse.

As robots become increasingly prevalent, our ethical responses to their mistreatment remain surprisingly unclear. This study, ‘Whether We Care, How We Reason: The Dual Role of Anthropomorphism and Moral Foundations in Robot Abuse’, investigates the psychological factors driving reactions to robot abuse, revealing that whether individuals extend moral consideration hinges on a robot’s perceived humanness. However, the way people reason about such consideration is shaped by their underlying moral foundations, specifically levels of progressivism. Ultimately, this suggests that designing ethically aligned robots and communicating responsible human-robot interaction policies requires nuanced attention to both appearance and individual values-but what implications does this have for the future of robot rights and welfare?

The Evolving Landscape of Social Interaction

The expanding presence of robots in everyday life is prompting a critical re-evaluation of human social behavior and ethical considerations. As these machines transition from purely functional tools to increasingly interactive companions and collaborators, questions emerge regarding appropriate modes of treatment and the potential for emotional attachment. Studies suggest that human responses to robots aren’t simply based on their mechanical nature, but are deeply rooted in established social norms and moral frameworks – the same ones governing interactions with other humans and even animals. This raises the possibility that how we treat robots may, in fact, serve as a revealing indicator of our own values, empathy levels, and the very foundations of human morality, potentially extending or even altering pre-existing ethical boundaries.

Humans readily ascribe human characteristics and intentions to non-human entities, a phenomenon known as anthropomorphism, and this tendency is powerfully demonstrated by the CASA Paradigm – Computers Are Social Actors. This framework posits that individuals unconsciously treat computers and robots as if they possess social cues, personalities, and even emotions, triggering the same social rules and expectations normally reserved for interactions with other people. Consequently, people often exhibit politeness, reciprocity, and even empathy towards robots, and conversely, may experience discomfort or guilt when perceiving mistreatment of these machines. This predisposition suggests that as robots become more sophisticated in mimicking human behavior, the lines between interacting with a tool and engaging with a social entity will become increasingly blurred, raising complex questions about how we define moral consideration and social responsibility.

The growing sophistication of social robotics presents a novel ethical challenge, forcing a re-evaluation of how moral considerations extend to non-biological entities. As robots increasingly mimic human appearance and behavior, the potential for both positive connection and harmful mistreatment becomes a pressing concern. This isn’t simply about preventing damage to a machine; rather, the act of interacting with a convincingly human-like robot may activate ingrained social norms and emotional responses, raising questions about the psychological impact of both kindness and cruelty. Consequently, researchers and ethicists are beginning to explore whether inflicting harm – even symbolic harm – on these entities could desensitize individuals to mistreatment of other humans, or conversely, if treating robots with respect fosters empathy and prosocial behavior. This emerging field demands careful consideration of the reciprocal relationship between human morality and the design of increasingly lifelike artificial companions.

The Foundations of Moral Response

Moral Foundations Theory posits that human moral reasoning is not based on a single, universal principle, but rather on a set of five psychologically distinct, innate foundations. These foundations are: Care, concerning the welfare of others, particularly those with whom one has close relationships; Fairness, relating to proportionality and justice in social exchanges; Loyalty, pertaining to allegiance to one’s in-group and the maintenance of group cohesion; Authority, focused on respect for hierarchy and tradition; and Sanctity, concerning purity and avoiding contamination. These foundations are considered universal in the sense that they appear across cultures, though the relative importance and expression of each foundation can vary significantly based on individual and cultural factors. The theory suggests that moral judgments are often made by intuitively applying one or more of these foundations to a given situation.

The five Moral Foundations – Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity – are not equally valued across all individuals or cultures. Research indicates substantial variation in the relative weighting of these foundations, meaning some people consistently prioritize, for example, Loyalty and Authority over Care and Fairness in their moral judgments. This differential prioritization directly influences ethical reasoning and subsequent behavioral responses; a culture strongly emphasizing Loyalty may view actions promoting group cohesion as morally superior, while a culture prioritizing Fairness might condemn the same actions as unjust if they disadvantage individuals. Consequently, moral disagreements frequently stem not from differing fundamental principles, but from varying degrees of importance assigned to these core foundations.

Progressive ideologies typically place a strong emphasis on the moral foundations of Care and Fairness, which prioritize the welfare and rights of individuals. This prioritization contrasts with a greater focus on Binding Foundations – Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity – which emphasize group cohesion and social order. Consequently, individuals identifying with progressive viewpoints may evaluate robots based on their perceived impact on individual well-being and equitable treatment, potentially exhibiting greater concern over issues like algorithmic bias or data privacy. This differs from those prioritizing Binding Foundations, who might assess robots based on their contribution to group goals, respect for established hierarchies, or adherence to traditional values.

The Moral Foundations Questionnaire, version 20 (MFQ-20), is a self-report measure designed to assess the degree to which individuals rely on each of the five moral foundations – Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity – when making moral judgments. The MFQ-20 utilizes a 4-point Likert scale to gauge agreement with a series of statements related to these foundations, generating scores for each. These scores are not absolute measures of moral character, but rather indicate the relative importance of each foundation for that individual. This quantified prioritization allows researchers to predict how individuals might react to morally ambiguous stimuli, including interactions with artificial agents, by linking foundation scores to specific emotional and behavioral responses. The questionnaire has demonstrated reliability and validity across multiple cultural contexts, facilitating comparative analyses of moral psychology.

Decoding Reactions to Artificial Harm

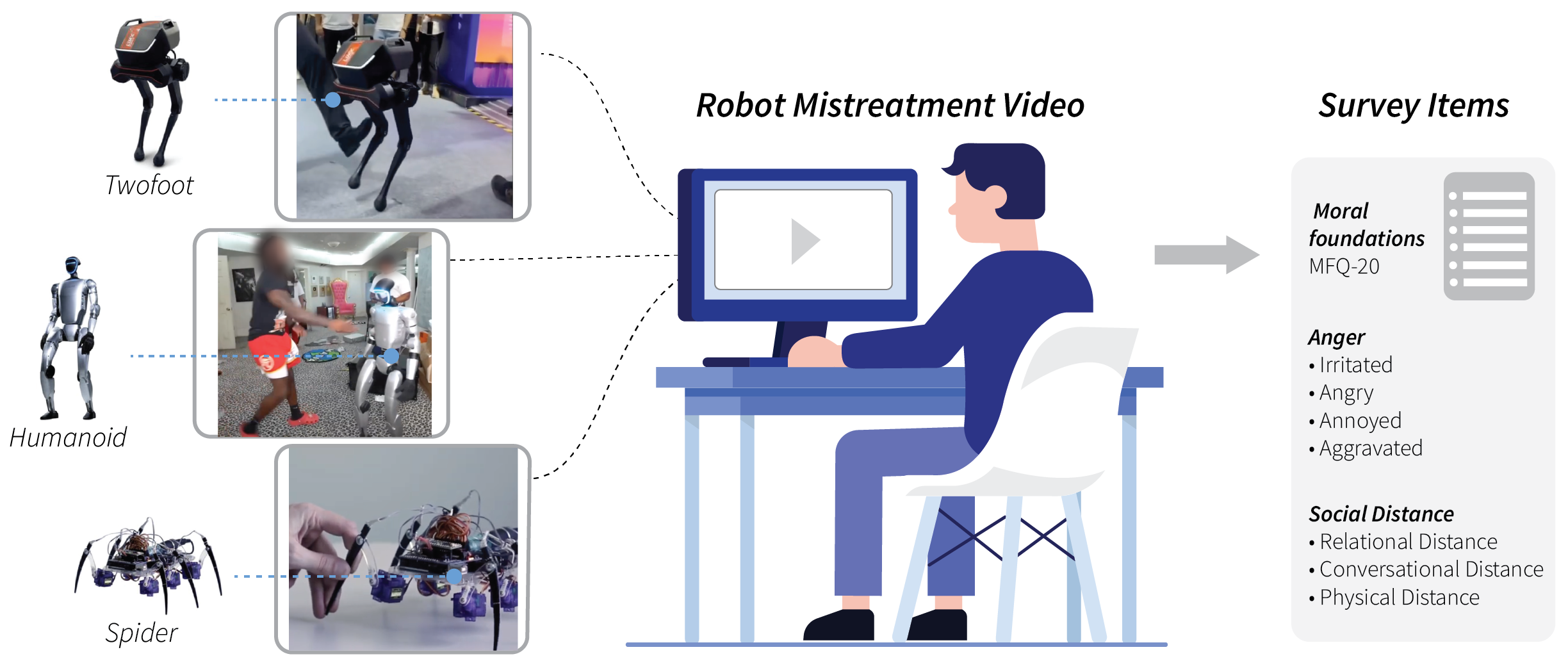

The research involved presenting participants with video stimuli depicting various forms of mistreatment directed towards robotic entities. These videos served as the basis for assessing individual moral reasoning processes related to robot abuse. Participants were exposed to scenarios involving different robot designs – a Spider Robot, a Twofoot Robot, and a Humanoid Robot – to determine how visual characteristics influenced perceptions of abusive acts and subsequent moral judgements. Data collection focused on participant responses to these stimuli, analyzed to identify patterns in justifications for, or condemnation of, the depicted behavior. The study aimed to empirically investigate the cognitive and emotional factors contributing to moral considerations regarding the treatment of artificial agents.

The experimental stimuli consisted of video depictions of interactions with three distinct robot designs: a Spider Robot, a Twofoot Robot, and a Humanoid Robot. These designs were selected to systematically vary the degree of anthropomorphism present, allowing researchers to assess the correlation between a robot’s human-like characteristics and participant perceptions of abusive behaviors. The Spider Robot, possessing minimal human resemblance, served as the baseline condition, while the Twofoot and Humanoid Robots represented increasing levels of anthropomorphic features, specifically in terms of body structure and potential for mimicking human movement and expression. This variation enabled a quantitative examination of how perceived similarity to humans influences moral considerations regarding mistreatment.

Thematic analysis of participant responses to videos depicting robot abuse identified recurring patterns in justifications and condemnations of the observed behavior. These patterns consistently reflected core tenets of established moral foundations theory, specifically variations in care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation. Justifications for abusive acts frequently centered on perceptions of the robot as a non-sentient object, thus minimizing concerns related to care-based moral foundations. Conversely, condemnations often invoked principles of fairness, particularly when the abuse appeared gratuitous or disproportionate, and occasionally extended to appeals regarding potential future harm should similar behavior be generalized to sentient beings. The prominence of these foundations varied depending on the specific abusive act depicted and the characteristics of the robot being abused, suggesting a nuanced relationship between moral reasoning and the perceived moral status of robotic entities.

Statistical analysis revealed a significant main effect of robot type on participant-reported anger levels (F(2,195) = 8.38, p < .001). This indicates that the design of the robot influenced the degree of emotional response to depictions of abuse. Specifically, robots exhibiting greater anthropomorphic features – the Humanoid and Twofoot robots – consistently elicited significantly higher levels of anger when subjected to mistreatment compared to the less anthropomorphic Spider robot. This suggests that perceived similarity to humans impacts the moral consideration given to robotic entities, triggering stronger emotional reactions when more human-like robots are abused.

The Shifting Boundaries of Empathy

Research indicates a compelling connection between how people perceive their social closeness to robots and their subsequent moral evaluations of mistreatment directed towards them. The study demonstrates that individuals who establish a sense of social proximity with robotic entities are more likely to strongly condemn abusive acts, mirroring the empathetic responses typically elicited by harm to other social beings. Conversely, those who maintain a greater sense of distance – perceiving the robot as a non-social object – tend to exhibit diminished moral outrage, sometimes rationalizing or minimizing the severity of the abuse. This suggests that the established level of social connection significantly influences the application of moral considerations, extending potentially to artificial agents as perceptions of relational closeness increase.

Research indicates a compelling correlation between perceived social connection with robots and the strength of moral condemnation towards abusive acts committed against them. Individuals who view robots as possessing qualities of sociality – exhibiting empathy, understanding, or even companionship – demonstrate a notably stronger negative response to observed abuse. This heightened reaction suggests that feelings of social closeness activate similar neural pathways involved in responding to harm inflicted upon other sentient beings, triggering a sense of moral obligation and protective concern. The study posits that as robots become increasingly sophisticated in their ability to mimic social cues and elicit emotional responses, human perceptions of their social status will correspondingly influence the degree to which abusive behavior is deemed unacceptable, potentially extending traditional moral frameworks to encompass artificial entities.

Research indicates that individuals who perceive substantial distance from robotic entities demonstrate a tendency to rationalize or minimize acts of abuse directed towards them. This phenomenon suggests a diminished sense of moral obligation, wherein the robot is not considered a subject deserving of empathetic concern, but rather as an object or tool. This perspective allows for the downplaying of harmful actions, as the perceived lack of social connection weakens the instinctive aversion to inflicting harm. Consequently, those maintaining greater distance may exhibit reduced condemnation of abusive behavior, potentially attributing less moral weight to the robot’s experience and framing the actions as inconsequential or even justifiable given the machine’s perceived status.

Statistical analysis demonstrates that the type of robot significantly influences how people perceive their relationship with it, both physically and emotionally. Specifically, multivariate tests revealed a notable effect on relational distance – how closely someone feels connected to the robot – as well as conversational distance, measuring comfort in interaction, and physical distance, the preferred amount of personal space. These effects were statistically significant, with F-values of 3.52, 3.17, and 7.08 respectively, all at the p < .05 level. This data reinforces the connection between a robot’s design – its degree of anthropomorphism – and how readily humans perceive social proximity, suggesting that certain characteristics foster a stronger sense of connection and, consequently, impact how people might react to its treatment.

The study illuminates a fundamental truth about complex systems: their inherent fragility. Every interaction, every extension of moral consideration – or lack thereof – towards a robotic entity is a signal from time, revealing the decay of pre-programmed expectations and the emergence of new ethical considerations. As Ken Thompson observed, “Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.” This resonates deeply with the research; the ‘code’ of human morality, when applied to novel entities, reveals its own limitations and necessitates constant refactoring. The degree of anthropomorphism acts as a catalyst, accelerating the revelation of these inherent flaws within our moral frameworks, demonstrating that even the most carefully constructed systems are subject to the relentless passage of time.

The Inevitable Fade

This work clarifies the initial conditions for extending moral consideration to artificial agents – a fleeting moment before inevitable disillusionment. Any perceived alignment between robot form and human expectation ages faster than anticipated; the novelty of anthropomorphic resemblance will yield to the stark realities of non-reciprocity. The study highlights a crucial, yet temporary, influence of moral foundations, specifically progressivism, on the manner of justification, not necessarily the presence of it. This suggests a predictable trajectory: as robots inevitably fail to meet projected empathetic standards, the rationale for moral consideration will shift – or erode – along lines already determined by pre-existing moral frameworks.

The challenge now lies in tracing the decay of these initial conditions. Future research must move beyond documenting whether moral consideration is extended and focus on the rate of its diminishment. Mapping the predictable failures of anthropomorphic appeal – the uncanny valley’s expansion, so to speak – will be more informative than seeking perpetual moral regard. Understanding how moral reasoning adapts – or fails to adapt – in the face of persistent robotic shortcomings represents a journey back along the arrow of time, revealing the limits of projected empathy.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry reinforces a fundamental principle: all systems degrade. The question isn’t preventing the decline of moral consideration for robots, but anticipating its form. The observed interplay between anthropomorphism and moral foundations provides a starting point for charting that decline, a necessary step toward accepting the inevitable return to instrumental valuation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.19826.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- PUBG Mobile collaborates with Apollo Automobil to bring its Hypercars this March 2026

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- Are Halstead & Upton Back Together After The 2026 One Chicago Corssover? Jay & Hailey’s Future Explained

- Heeseung is leaving Enhypen to go solo. K-pop group will continue with six members

- Overwatch Domina counters

2026-01-28 17:22