Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach combines artificial intelligence with optimization techniques to rapidly create more effective robot designs.

This review explores the integration of large language models and black-box optimization for multi-objective robot design, achieving Pareto-optimal solutions for modular robots and complex inverse kinematics problems.

Despite advances in robot design optimization, achieving efficient exploration of complex, multi-objective design spaces remains a significant challenge. This is addressed in ‘Efficient Robot Design with Multi-Objective Black-Box Optimization and Large Language Models’, which proposes a novel method integrating large language models (LLMs) with black-box optimization to accelerate the discovery of high-performing robot designs. By leveraging LLMs to guide the sampling process alongside traditional optimization, this work demonstrates improved efficiency in navigating complex design landscapes and identifying Pareto-optimal solutions. Could this approach herald a new era of AI-driven robot design, enabling the rapid creation of robots tailored to increasingly complex tasks?

The Challenge of Automated Robotic Form Discovery

Historically, the creation of effective robots has depended on a painstaking cycle of human-led adjustments and repeated physical testing. Engineers would manually tweak parameters – limb lengths, joint stiffness, motor strengths – building and evaluating prototypes until acceptable performance was achieved. This iterative refinement, while yielding functional machines, is remarkably slow and rarely produces truly optimal designs. The process is susceptible to human bias and often converges on solutions that are ‘good enough’ rather than those that maximize efficiency, adaptability, or energy conservation. Consequently, significant improvements in robotic capabilities have been limited by the constraints of this largely manual, trial-and-error approach, hindering the development of robots capable of tackling increasingly complex tasks.

The pursuit of truly adaptable robotic movement necessitates a meticulous evaluation of numerous interconnected parameters – from limb lengths and joint arrangements to the distribution of mass and the characteristics of actuators. This complexity doesn’t simply add to the engineering challenge; it creates a design space of almost infinite possibilities. Each parameter subtly influences the robot’s ability to navigate diverse terrains, manipulate objects with precision, and conserve energy during locomotion. Consequently, even seemingly minor adjustments can yield significant improvements – or detrimental consequences – in performance. Exploring this vast parameter landscape effectively requires innovative approaches that surpass the limitations of traditional trial-and-error methods, demanding computational strategies capable of efficiently searching for optimal configurations within this high-dimensional and often unintuitive design space.

Conventional optimization techniques often falter when applied to robot body design due to the sheer complexity of the problem. The design space isn’t simply large – it’s non-linear, meaning small changes to one parameter can produce disproportionately large and unpredictable effects on overall performance. This presents a significant challenge because most optimization algorithms are built on the assumption of relatively smooth, predictable relationships between variables. As the number of design parameters – body segment lengths, joint types, actuator sizes – increases, the dimensionality of the search space explodes, creating countless local optima that can trap algorithms before they reach a truly optimal solution. Consequently, finding robot morphologies that effectively balance maneuverability, stability, and energy efficiency requires methods capable of navigating these intricate, high-dimensional landscapes, pushing the boundaries of current optimization strategies.

Leveraging Linguistic Intelligence for Robotic Morphology

Large Language Models (LLMs) are utilized to propose values for robot body design parameters, operating on problem descriptions defined at a high level of abstraction. The LLMs accept inputs specifying desired robot capabilities and environmental constraints, then generate candidate parameter sets – including dimensions, joint configurations, and material properties – intended to satisfy those requirements. This generation process is not a random search; the LLMs leverage their pre-trained knowledge to propose plausible designs. Furthermore, the system incorporates feedback mechanisms allowing iterative refinement of parameter suggestions based on simulation results or real-world performance data, enabling the LLM to adapt and improve its design proposals over time.

Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning, implemented within the Large Language Models (LLMs), functions by prompting the model to explicitly detail the intermediate steps and logical inferences leading to each proposed robot body design parameter. This process moves beyond simply outputting a value; the LLM generates a textual justification explaining why a particular parameter is suggested in relation to the specified problem setting. The articulated rationale includes the connection between high-level task requirements and the chosen numerical value, thereby enhancing the transparency of the design process and providing users with increased control over the generated parameters. This allows for human oversight, targeted adjustments, and facilitates debugging of the LLM’s reasoning process.

Traditional robot design optimization relies on numerical methods to iteratively refine parameters within a defined search space. This LLM-driven approach fundamentally alters this process by replacing the purely iterative numerical search with a guided exploration informed by LLM-generated insights. Instead of solely evaluating parameter sets against a fitness function, the LLM proposes parameter values accompanied by a rationale explaining how those values address the specified problem settings. This allows the optimization to benefit from the LLM’s learned knowledge and reasoning capabilities, potentially accelerating convergence and identifying solutions that a purely numerical search might miss. The LLM effectively functions as a knowledge-based heuristic, directing the search towards more promising regions of the design space.

Multi-Objective Optimization and Performance Quantification

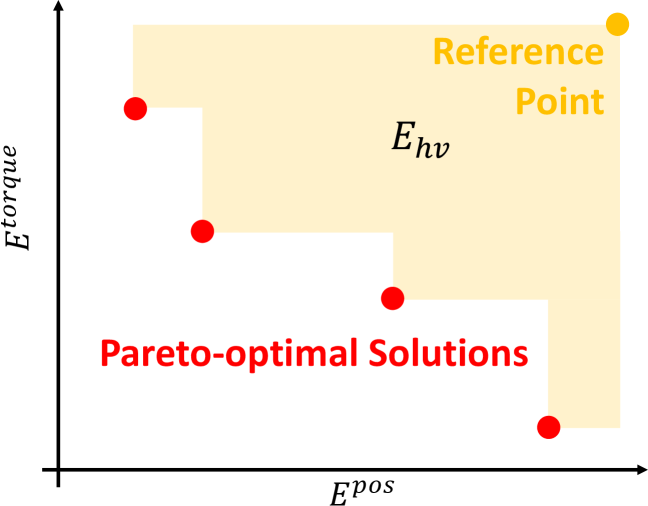

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) is employed to concurrently minimize multiple, often conflicting, performance goals during robot design. This approach differs from single-objective optimization by seeking a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, representing trade-offs between objectives rather than a single best solution. In the context of robotic systems, MOO enables the simultaneous reduction of competing factors such as required torque – minimizing energy consumption and actuator stress – and position error, which directly impacts task accuracy. The resulting Pareto front provides designers with a range of viable solutions, allowing selection based on specific application priorities and constraints. Formally, MOO seeks to find $x \in X$ that minimizes $f(x) = [f_1(x), f_2(x), …, f_k(x)]$ where $f_i$ are the objective functions and $X$ is the feasible design space.

The robot body design optimization process centers on key kinematic parameters that define the robot’s physical structure. Specifically, the configuration of joints – including their type and range of motion – and the lengths of the connecting links are treated as variables subject to optimization. Altering these parameters directly impacts the robot’s workspace, dexterity, and ability to achieve desired trajectories. The optimization algorithm explores different combinations of joint configurations and link lengths to identify designs that minimize competing objectives, such as required torque and positioning error, ultimately shaping the robot’s physical form to best suit the target application.

Performance evaluation of robot designs utilized the Hypervolume metric ($Ehv$) to quantify the Pareto front, enabling comparison across different optimization configurations. Results indicate that integrating Large Language Model (LLM) sampling with a ratio of one LLM step for every ten black-box optimization steps yielded the highest $Ehv$ values consistently across all tested target operation points. This configuration outperformed alternatives, demonstrating superior performance in simultaneously minimizing competing objectives related to robot body design parameters such as joint configuration and link length.

Analysis of experimental results indicates that the integration of Large Language Model (LLM)-based sampling into the optimization process significantly reduces result variance. Specifically, the Standard Deviation of Hypervolume ($\sigma_{h\nu}$) was consistently lower when utilizing LLM sampling compared to traditional black-box optimization methods. This lower standard deviation demonstrates improved stability and repeatability in identifying optimal robot designs, indicating that the LLM-based approach minimizes the impact of random fluctuations during the optimization process and converges more reliably on high-performing solutions.

Bridging the Gap Between Simulation and Physical Realization

The design process incorporates Inverse Kinematics (IK) as a fundamental component of the optimization loop, ensuring that proposed robotic designs are not merely theoretical constructs but physically realizable solutions. By integrating IK, the system assesses whether a robot, parameterized by the generated designs, can actually achieve specified poses and movements. This proactive feasibility check operates during optimization, effectively guiding the design process towards solutions that respect the robot’s kinematic limitations. Consequently, the resulting designs are inherently more practical, reducing the need for costly redesigns or the rejection of otherwise promising configurations that prove impossible to implement in the physical world. The inclusion of IK therefore bridges the critical gap between computational optimization and successful robotic deployment.

Inverse Kinematics serves as a critical verification tool, assessing whether a robot, defined by newly proposed parameters, can physically realize intended movements and orientations. By inputting desired end-effector poses and trajectories, the system calculates the necessary joint angles, effectively simulating the robot’s performance. If the IK solver fails to find a valid solution-meaning the robot cannot reach the specified pose without exceeding joint limits or colliding with itself-the design parameters are flagged for adjustment. This iterative process ensures that optimized designs aren’t merely mathematically efficient but also mechanically feasible, bridging the gap between simulation and successful real-world robotic operation. The ability to validate proposed designs with IK drastically reduces the risk of generating plans that are impossible for the robot to execute, contributing to robust and reliable robotic systems.

The translation of optimized robotic designs into functional systems often encounters challenges stemming from the discrepancies between simulation and physical reality. This validation step, incorporating Inverse Kinematics, directly addresses this issue by rigorously testing whether a proposed robotic configuration can actually achieve the intended motions and poses. Without such verification, designs might appear optimal in theory but prove impossible or unstable when implemented on a physical robot due to limitations in joint ranges, actuator capabilities, or unforeseen environmental interactions. By ensuring feasibility before fabrication or deployment, this process minimizes costly redesigns and accelerates the development of robots capable of performing complex tasks in the real world. It represents a critical bridge, transforming abstract mathematical solutions into tangible robotic performance.

The pursuit of efficient robot design, as detailed in this work, mirrors a fundamental principle of systemic integrity. The method’s integration of black-box optimization and large language models seeks to navigate complex design spaces, identifying Pareto optimal solutions without relying on pre-defined gradients. This holistic approach acknowledges that a robot’s overall performance isn’t simply the sum of its parts, but emerges from the interplay of numerous variables. As Ada Lovelace observed, “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.” This resonates with the current study; the LLM doesn’t create designs, but intelligently explores the possibilities defined by the optimization process, effectively translating design goals into achievable robotic structures.

Future Directions

The pursuit of efficient robot design, as demonstrated by this work, inevitably reveals the inherent trade-offs within any complex system. Achieving Pareto optimality across multiple objectives does not represent a final solution, but rather a mapping of the boundaries of possibility – a refined understanding of where compromise becomes necessary. The current approach, while promising, remains tethered to the limitations of its constituent parts: the search space defined by modularity, and the interpretative capacity of the large language model. Each optimization, each apparent gain in performance, introduces new tension points, subtly shifting the burden of inefficiency elsewhere within the system.

Future work must address the question of scalability. Can this methodology be extended to designs far exceeding the complexity of current modular robots, or will the combinatorial explosion of possibilities overwhelm even the most sophisticated optimization algorithms? More critically, the reliance on black-box optimization obscures the underlying principles governing robot behavior. A truly elegant design emerges not from blind search, but from a deep understanding of structure and its dictates.

The next logical step lies in integrating this optimization framework with methods for extracting and codifying design knowledge. The large language model, currently used as a descriptive tool, could potentially become a generative one, capable of proposing novel design solutions based on learned principles. This would require moving beyond purely quantitative metrics and incorporating qualitative considerations – robustness, maintainability, and even aesthetic qualities – into the optimization process. Ultimately, the architecture is the system’s behavior over time, not a diagram on paper.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2511.17178.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Vampire’s Fall 2 redeem codes and how to use them (June 2025)

- Mobile Legends January 2026 Leaks: Upcoming new skins, heroes, events and more

- World Eternal Online promo codes and how to use them (September 2025)

- Clash Royale Season 79 “Fire and Ice” January 2026 Update and Balance Changes

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- M7 Pass Event Guide: All you need to know

- Clash Royale Furnace Evolution best decks guide

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- How to find the Roaming Oak Tree in Heartopia

2025-11-24 09:51