Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging the power of diffusion models and Fourier transforms to design and create novel crystalline structures with unprecedented efficiency.

A new approach utilizes latent diffusion in reciprocal space to enable scalable generative modeling of crystal structures.

Generating novel crystalline materials requires overcoming the challenges of representing periodic structures with complex symmetries and compositional diversity. This is addressed in ‘Fourier Transformers for Latent Crystallographic Diffusion and Generative Modeling’, which introduces a reciprocal-space representation of crystals based on truncated Fourier transforms, enabling efficient generative modeling. By operating on complex-valued Fourier coefficients within a latent diffusion framework, the approach reconstructs unit cells containing up to 108 atoms per species while naturally accommodating crystallographic constraints. Could this reciprocal-space approach unlock scalable generation of entirely new, physically realistic materials with tailored properties?

Decoding the Crystal Lattice: Beyond the Limits of Observation

The bedrock of materials science relies on a thorough understanding of crystalline structure, as atomic arrangement dictates a material’s properties. However, traditional techniques for determining this structure, most notably X-ray diffraction, present significant challenges. While powerful, these methods require substantial computational resources, particularly when analyzing large or complex unit cells. The process involves solving intricate mathematical equations to interpret diffraction patterns, a task that becomes exponentially more demanding with increasing structural complexity and disorder. Consequently, characterizing materials with unconventional or imperfect crystalline arrangements can be both time-consuming and prone to inaccuracies, hindering progress in fields ranging from drug discovery to advanced materials design.

The sluggish pace of materials discovery is directly linked to the difficulties in accurately determining crystal structures. A comprehensive understanding of atomic arrangement is crucial for predicting a material’s behavior – its strength, conductivity, or reactivity – yet conventional methods often present bottlenecks. The inability to swiftly and reliably map these structures restricts the design of novel materials with targeted properties, forcing researchers to rely heavily on trial-and-error experimentation. This creates a significant demand for computational techniques and experimental methodologies that can overcome these limitations, enabling a more efficient and predictive approach to materials science and ultimately accelerating the development of advanced technologies.

Conventional techniques for determining crystal structure frequently necessitate compromises in precision when confronted with materials exhibiting disorder or intricate arrangements. These methods often depend on simplifying assumptions to render calculations manageable, potentially obscuring crucial details about atomic positions and interactions. While sufficient for many well-ordered crystalline solids, these approximations can introduce significant errors when applied to materials where atoms deviate from perfectly regular patterns – such as alloys, amorphous solids, or compounds with complex defects. Consequently, the resulting structural models may not accurately reflect the true arrangement of atoms, hindering the reliable prediction of material properties and limiting the efficacy of computational materials design. This inherent limitation drives the development of more sophisticated techniques capable of resolving structural details without sacrificing accuracy, even in the face of complexity.

Reimagining Structure: Crystals in Reciprocal Space

Representing a crystal structure in reciprocal space via Fourier transforms provides a computationally efficient alternative to direct real-space calculations. This transformation converts the description from a function of real-space coordinates [latex] \mathbf{r} [/latex] to a function of reciprocal space vectors [latex] \mathbf{G} [/latex]. Because crystals exhibit periodicity, their reciprocal space representation consists of discrete points – the Bragg peaks – significantly reducing the number of variables needed for description compared to the continuous real-space lattice. This compact representation simplifies calculations involving diffraction, such as those found in X-ray or neutron scattering, and facilitates the efficient storage and manipulation of structural data. The Fourier transform inherently encodes the translational symmetry of the crystal, allowing calculations to be performed in a basis that naturally reflects this symmetry.

The reciprocal space representation of a crystal lattice directly reflects its translational symmetry and, consequently, its long-range order. Unlike real-space descriptions which require defining unit cells and considering periodic boundary conditions for calculations, the reciprocal lattice consists of discrete points corresponding to the fundamental vectors of the real-space lattice. The intensity of these points, derived from the Fourier transform of the crystal’s electron density, is proportional to the structure factor and directly reveals the amplitudes of diffracted waves. This inherent encoding of periodicity allows for efficient analysis of diffraction patterns, determination of crystal symmetry, and prediction of allowed reflections, simplifying calculations related to phenomena like X-ray diffraction and electron microscopy compared to methods requiring explicit modeling of the real-space lattice.

The accurate determination of crystal structure from diffraction data relies on preserving phase information, which is lost in traditional intensity-only measurements. Employing complex-valued tokens in a representation of the crystal structure allows for the encoding of both amplitude and phase. Specifically, the phase component, represented by the argument of the complex number, is critical because it dictates the interference of diffracted waves; without it, an infinite number of real-space structures could potentially fit the observed diffraction pattern. The complex values effectively represent the [latex]\sqrt{I}e^{i\phi}[/latex] components of the diffracted waves, where [latex]I[/latex] is the intensity and φ is the phase angle, allowing for unambiguous reconstruction of the electron density and, consequently, the crystal structure.

The reciprocal space representation of crystal structures is particularly amenable to integration with neural network architectures due to its inherent mathematical properties. Specifically, the Fourier transform-based representation converts translational symmetry into point symmetry, reducing the input dimensionality and computational complexity for neural networks. This allows networks to efficiently learn and generalize patterns across different crystal orientations and compositions. Furthermore, the fixed-size input afforded by the reciprocal lattice simplifies network design and training, while the preservation of phase information – crucial for diffraction patterns – provides a direct link between the network’s learned features and experimentally observable quantities. Consequently, these networks can be trained to predict material properties, identify crystal structures from limited data, or even design novel materials with desired characteristics with increased accuracy and efficiency compared to methods operating directly on real-space data.

Forging Structure from Noise: Latent Diffusion for Crystal Prediction

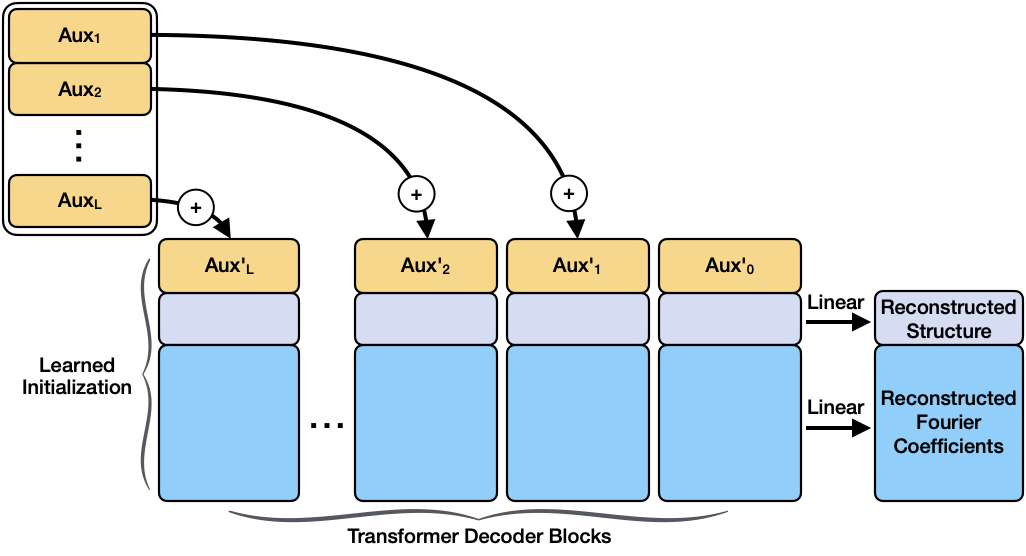

A Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) for crystal structure generation utilizes a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to map high-dimensional crystal data into a lower-dimensional latent space. This latent representation is then processed by a Transformer architecture, enabling the model to learn complex relationships and dependencies within the crystal structures. The Transformer’s attention mechanism allows the model to focus on relevant features during generation. By performing the diffusion process – iteratively adding and removing noise – within this latent space, the LDM efficiently generates new crystal structures. This approach reduces computational demands compared to operating directly on the high-dimensional structural data, while maintaining the ability to produce realistic and diverse crystal configurations. The VAE component ensures that generated latent vectors can be decoded back into valid crystal structures, and the Transformer enables the modeling of long-range dependencies essential for structural plausibility.

The latent diffusion model generates novel crystal structures by operating within a reduced-dimensionality latent space learned from a training set of existing structures. This latent representation captures the essential features of crystal geometry and chemical composition, allowing the model to generate new structures by sampling from this learned distribution. Crucially, the latent space is designed to be controllable; specific attributes, such as unit cell parameters or desired chemical motifs, can be incorporated as conditioning variables during the generation process. This enables targeted structure prediction, allowing researchers to explore a range of plausible crystal structures with pre-defined characteristics, and facilitates the discovery of materials with desired properties without exhaustively searching the full configuration space.

RMS Normalization and Nonzero-Element Scheduling are implemented to address challenges inherent in training diffusion models for crystal structure prediction. RMS Normalization, applied to the intermediate feature maps, stabilizes training by preventing activations from becoming excessively large or vanishing, thereby maintaining gradient flow. Nonzero-Element Scheduling, during the diffusion process, gradually increases the proportion of non-zero elements in the noise schedule; this ensures a more controlled and efficient denoising process, particularly at the initial stages where significant structural information is absent, and prevents premature convergence to unrealistic structures. These techniques collectively reduce the computational cost and accelerate convergence without sacrificing the quality of generated crystal structures.

RoPE3D (Rotary Positional Embeddings for 3D) is a positional encoding scheme integrated into the latent diffusion model to provide spatial awareness during crystal structure generation. Traditional positional encodings can struggle with generalizing to unseen 3D arrangements; RoPE3D addresses this by representing positional information through rotation matrices applied in 3D space. This allows the model to effectively capture the relative positions of atoms within the crystal lattice, which is essential for maintaining structural plausibility and generating physically realistic crystals. The method encodes 3D coordinates by rotating vectors based on their position, enabling the Transformer architecture to better understand and extrapolate spatial relationships, ultimately improving the quality and accuracy of generated crystal structures.

From Prediction to Reality: Reconstructing the Atomic Landscape

The translation of a model’s internal, compressed representation of a structure into a physically realizable arrangement of atoms relies on sophisticated coordinate recovery techniques. These methods, crucially employing Rational Grid Snapping, effectively map the latent representation – a lower-dimensional encoding of structural information – back into a three-dimensional space of atomic coordinates. Rational Grid Snapping allows for precise placement of atoms onto a grid defined by rational numbers, avoiding the limitations of standard grid systems and ensuring accurate reconstruction even for complex crystal structures. This process doesn’t merely predict where atoms should be, but actively reconstructs their spatial coordinates, offering a pathway from abstract prediction to concrete, physically meaningful structural models.

The culmination of the model’s predictive capabilities lies in its ability to generate a physically interpretable representation of atomic structure. Rather than remaining confined to a latent, abstract space, the model translates its predictions into a three-dimensional arrangement of atoms, defining their precise coordinates in real space. This transformation is crucial for bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental validation; it allows researchers to directly compare the model’s output to data obtained from techniques like X-ray diffraction or electron microscopy. By effectively ‘decoding’ the latent representation, the model doesn’t just identify patterns – it reconstructs the actual structural organization of the material, providing a tangible and meaningful result that can be further analyzed and utilized in materials science investigations.

The predictive power of this model extends to a complete reconstruction of atomic structures, demonstrating an ability to accurately define the position of each atom within a unit cell. Critically, the system achieves full recovery – meaning no positional errors – for structures containing up to 108 atoms of a single chemical species. This capacity represents a significant advancement, allowing for detailed structural elucidation even in complex arrangements. The model’s precision at this scale suggests it can reliably map the latent representation – the model’s internal understanding of the structure – back into a physically meaningful, three-dimensional arrangement of atoms, opening avenues for advanced materials discovery and analysis.

A critical validation of the reconstruction process lies in the remarkably low signal reconstruction error; this metric consistently remains below the inherent noise scale of the decoder. This indicates that the recovered atomic coordinates are not simply plausible outputs, but fall comfortably within the operational range of the model’s predictive capacity. Essentially, the reconstructed signals aren’t being ‘forced’ into existence at the edge of the model’s limits, but rather represent confident predictions well within established parameters. This fidelity is crucial, ensuring the recovered structures are reliable and reflect a genuine understanding of the underlying physical arrangement, rather than artifacts of the reconstruction process itself.

Beyond the Horizon: Charting the Future of Crystal Structure Prediction

Recent advancements in crystal structure prediction leverage diffusion models, a class of generative machine learning algorithms, but their performance is acutely sensitive to the distribution of noise added during the training process. Researchers have found that replacing the traditionally used Gaussian noise with a Laplace distribution significantly enhances both the robustness and fidelity of the generated structures. The Laplace distribution, characterized by heavier tails, allows the model to better handle outliers and explore a wider range of possible configurations, preventing it from becoming trapped in local minima during structure generation. This approach effectively guides the model toward more stable and physically realistic crystal structures, ultimately improving the accuracy and reliability of in silico materials discovery and design.

The predictive power of this crystal structure modeling relies heavily on the diversity of the data used for training. Currently, many models are limited by datasets that primarily feature common materials and symmetry types; expanding this base is crucial for broader applicability. Incorporating data representing a wider spectrum of chemical compositions, including those with complex or unusual arrangements, will enable the model to extrapolate beyond known structures and explore previously uncharted chemical space. Furthermore, explicitly including examples of all 230 space groups – the mathematical descriptions of crystal symmetries – will address current biases towards simpler, more frequently observed symmetries, ultimately allowing for the prediction of materials with far greater structural complexity and potentially unlocking novel functionalities.

Refining crystal structure prediction benefits from techniques that prioritize meaningful data within the modeling process; signal-to-noise regularization offers a promising avenue for achieving this. By strategically emphasizing the signal – the essential features defining a stable crystal structure – and suppressing noise, the model’s predictive power increases and spurious solutions are minimized. This approach doesn’t simply add more data, but rather intelligently weights existing information, allowing the model to discern crucial atomic arrangements from less important variations. Consequently, the resulting structures exhibit enhanced accuracy and physical realism, facilitating the identification of genuinely stable configurations and accelerating materials discovery by reducing the computational burden of sifting through irrelevant possibilities.

The advent of accurate crystal structure prediction techniques stands poised to dramatically reshape the field of materials design. By circumventing traditional, often serendipitous, discovery methods, researchers envision a future where materials are not simply found, but created with specific, desired characteristics. This computational approach allows for the systematic exploration of vast chemical spaces, identifying compounds predicted to exhibit exceptional properties – from superconductivity and high energy density to tailored optical and mechanical behaviors. Consequently, the potential impact spans numerous sectors, including energy storage, aerospace engineering, and biomedical implants, promising a new era of materials innovation driven by predictive power and customized functionality.

The pursuit of generative models for crystal structures, as detailed in this work, inherently involves probing the boundaries of what’s computationally feasible. It’s a process of deconstruction and reconstruction, revealing the underlying principles governing material formation. This resonates with the sentiment expressed by John von Neumann: “The best way to predict the future is to invent it.” The researchers didn’t simply accept existing limitations in modeling complex crystalline materials; instead, they actively sought to redefine the possibilities through a novel reciprocal-space representation and latent diffusion techniques. Every advancement in scalable generative modeling, much like every carefully crafted algorithm, is a testament to the power of intellectual invention, a deliberate act of shaping reality rather than merely observing it.

What Remains to Be Seen?

The work presented here doesn’t so much solve the problem of crystal structure generation as relocate it. Shifting to reciprocal space, leveraging Fourier transforms and latent diffusion, is a clever sidestep, undeniably. But it merely exchanges one set of computational bottlenecks for another-and introduces a new dependence on the quality of the latent space itself. The true test will lie in pushing this framework beyond idealized structures, towards materials riddled with defects, disorder, and the messy realities of synthesis.

One suspects the limitations aren’t inherent to the method, but to the current assumptions about what constitutes “generative” in this context. Current approaches largely focus on topology – the arrangement of atoms. But materials properties aren’t solely dictated by where atoms are, but how they move, vibrate, and interact. A truly comprehensive model would need to incorporate dynamics, effectively simulating not just static structures, but the time-dependent behavior of matter.

Ultimately, this research reinforces a familiar truth: reality is open source-it’s just that the code remains largely unread. Each advance in generative modeling isn’t a destination, but a more powerful set of debugging tools. The next iteration won’t be about creating more crystals, but about understanding-and therefore controlling-the fundamental rules governing their existence.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12045.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Christopher Nolan’s Highest-Grossing Movies, Ranked by Box Office Earnings

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Are Halstead & Upton Back Together After The 2026 One Chicago Corssover? Jay & Hailey’s Future Explained

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

- KAS PREDICTION. KAS cryptocurrency

2026-02-15 13:05