Most people recognize the song “On the Good Ship Lollipop,” famously sung by Shirley Temple. It’s become a well-known reference point, appearing in unexpected places like stories about the Chicago mafia – it was a nickname for a group in Cicero – and the TV show “The Simpsons.”

If you’re not familiar with the 1934 movie “Bright Eyes,” you might be surprised to learn that the “ship” mentioned in the song is actually an airplane. The song was originally performed by Shirley Temple’s character while she was driving around one of Los Angeles’ earliest airports, the Grand Central Air Terminal in Glendale.

You can still catch a glimpse of it if you drive along Grand Central Avenue, which cuts through Disney’s Grand Central Creative Campus.

Originally built in 1929 and beautifully restored by Disney in 2014, this building—designed in the Spanish Revival and Art Deco styles—is the last remaining structure from the old airport.

This airport witnessed many historic moments in aviation and entertainment. Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh launched their pioneering L.A. to New York airline route here – a remarkably quick 50-hour flight for the time! Aviator Laura Ingalls also made history as the first woman to fly solo across the country, from the East Coast to the West. Over the years, countless stars and influential figures arrived and departed, making it a hub for the glamorous world of early Hollywood. The location also served as a backdrop for numerous films, including Howard Hughes’ 1930 epic “Hell’s Angels” and the 1933 James Cagney film “Lady Killer.”

California

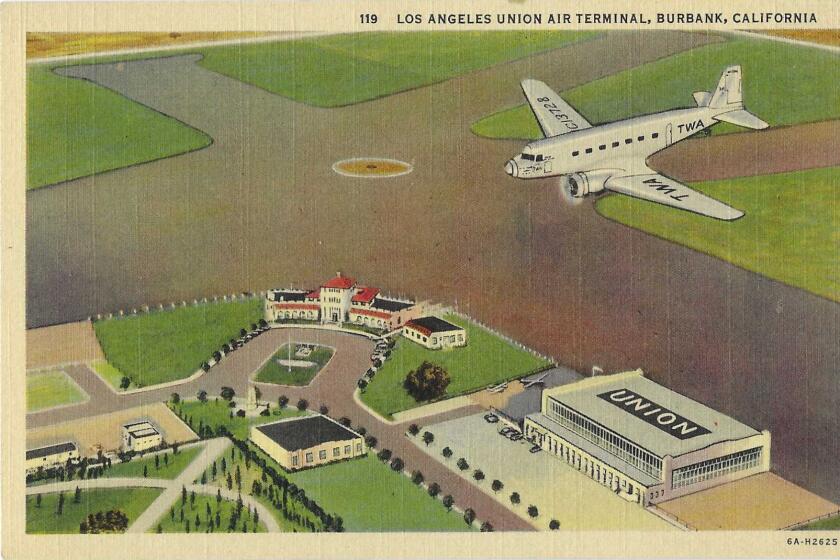

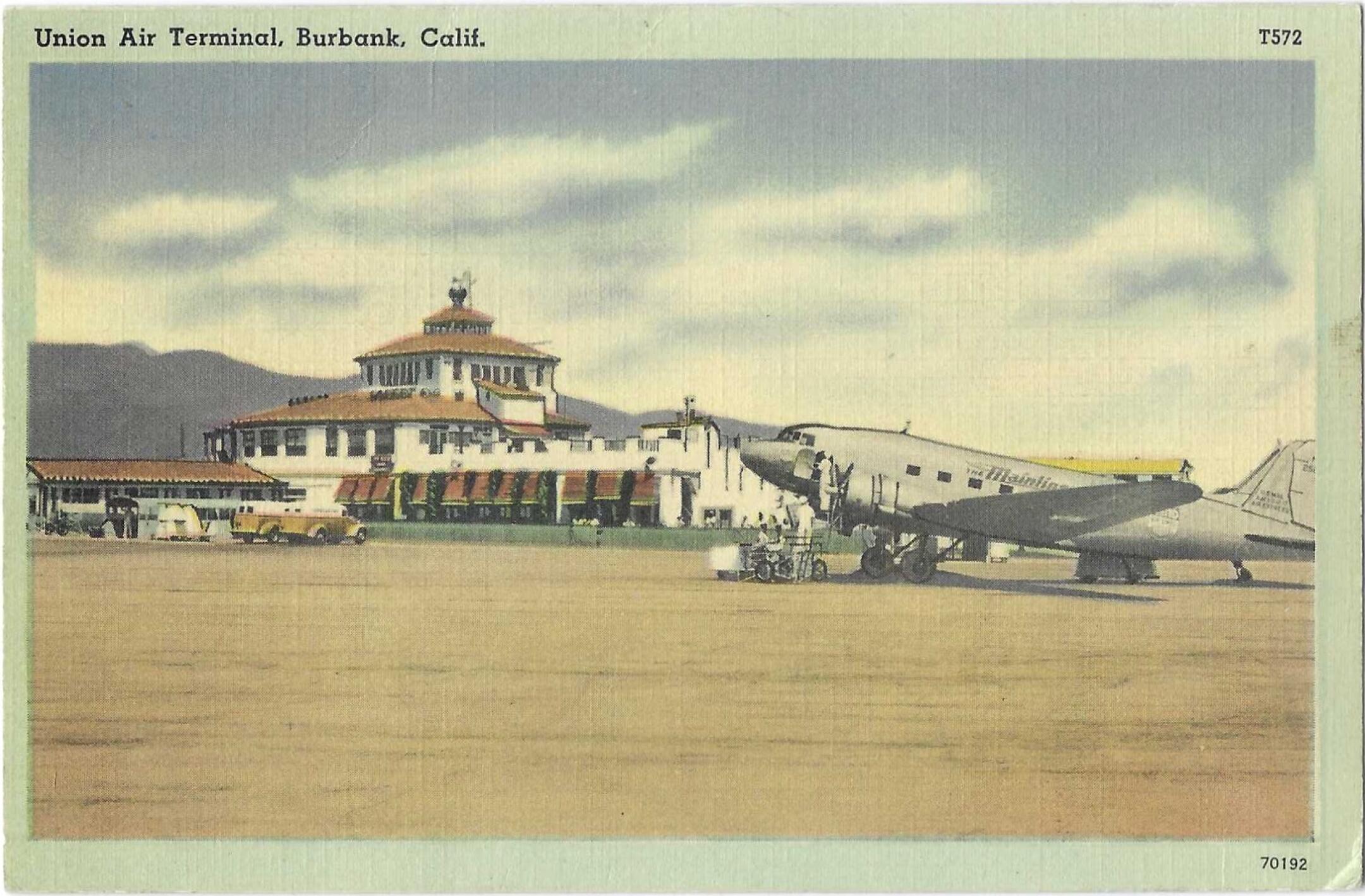

Old postcards offer glimpses of airports as they looked in the past – including some that are still around and others that have disappeared.

Despite often being associated with the iconic airport scene from “Casablanca,” it wasn’t actually filmed here. Most sources indicate the scene took place at Van Nuys Airport instead.

It’s fitting that Disney now occupies the historic Grand Central Air Terminal, hosting offices and events – and still offering tours from time to time. Hollywood and aviation have always been closely linked, from the earliest, blurry footage of the Wright brothers to current concerns about celebrity jet emissions. It’s a relationship that has been both helpful and, at times, heartbreaking.

With the holidays approaching and many people planning to travel by plane and see movies, it’s interesting to think about how Hollywood actually played a role in shaping the world of air travel.

At the start of the 1900s, Los Angeles had pleasant weather and plenty of open space, making it an ideal location for the growing industries of aviation and filmmaking.

Hollywood power players and planes

Grand Central Air Terminal wasn’t the first airport in the area. Even before World War I, wealthy and forward-thinking people in Los Angeles were fascinated by airplanes. Back in 1910, over 200,000 people came to watch the Los Angeles International Air Meet, which took place at Dominguez Field, now part of Rancho Dominguez.

Early airplane builders who would later form or be succeeded by companies like Lockheed, Douglas, and Northrop began establishing themselves on the West Coast. Around this time, L.C. Brand, known as the “father of Glendale,” created a landing strip near his home (which is now the Brand Library), and film producer Thomas Ince built Ince Field in Venice for stunt pilots. In 1914, Ince Field became the first officially recognized airport on the West Coast.

After World War I, the Los Angeles area quickly became a hub for aviation, with reports suggesting as many as 53 airports within a 10-mile radius of downtown. While Howard Hughes is the most well-known figure connecting the worlds of filmmaking and flight – he made movies, led RKO Pictures, and founded Hughes Aircraft, developing groundbreaking aircraft and later managing Trans World Airlines – he wasn’t alone in pursuing both passions.

Lifestyle

Each neighborhood in Los Angeles has its own unique history. Here’s the story of how I unexpectedly learned about my house’s ties to both the early days of Hollywood and the world of aviation.

In 1918, filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille started Mercury Aviation Co., the world’s first airline offering regularly scheduled flights. He also built an airfield, DeMille Field No. 1, at Melrose and Fairfax avenues. Later, the first passenger flight from New York to Los Angeles touched down at DeMille Field No. 2, located at Wilshire and Fairfax.

In 1919, Charlie Chaplin’s brother, Sydney, who also managed his business affairs, constructed an airfield just across the street from where he lived, on land bordered by Fairfax, Wilshire, and La Cienega boulevards. It’s something to remember next time you’re driving on La Cienega and trying to turn!

Chaplin and DeMille quickly learned that running an airline wasn’t as lucrative as they’d hoped. Los Angeles’s airports had limited space, making it difficult to handle bigger planes, and the land itself became more valuable for building. However, the real connection was how aviation and filmmaking actually helped each other grow – each industry benefited from the other’s development.

Aviation in film

After World War I, many pilots came to Los Angeles hoping to work as stunt performers, and some even became movie stars. Reginald Denny, a former gunner for the Royal Air Force, was one of them. He performed stunts with the 13 Black Cats at Burdett Field (now in Inglewood, near 94th Street and Western Avenue) and acted in numerous films, including versions of “Anna Karenina,” “The Little Minister,” and “Rebecca.”

Stunt piloting, even for films, was a very dangerous job. Frank Stites tragically died while performing a stunt during the 1915 celebration of Universal Studios’ grand opening. Some people believe his ghost still wanders the studio backlot.

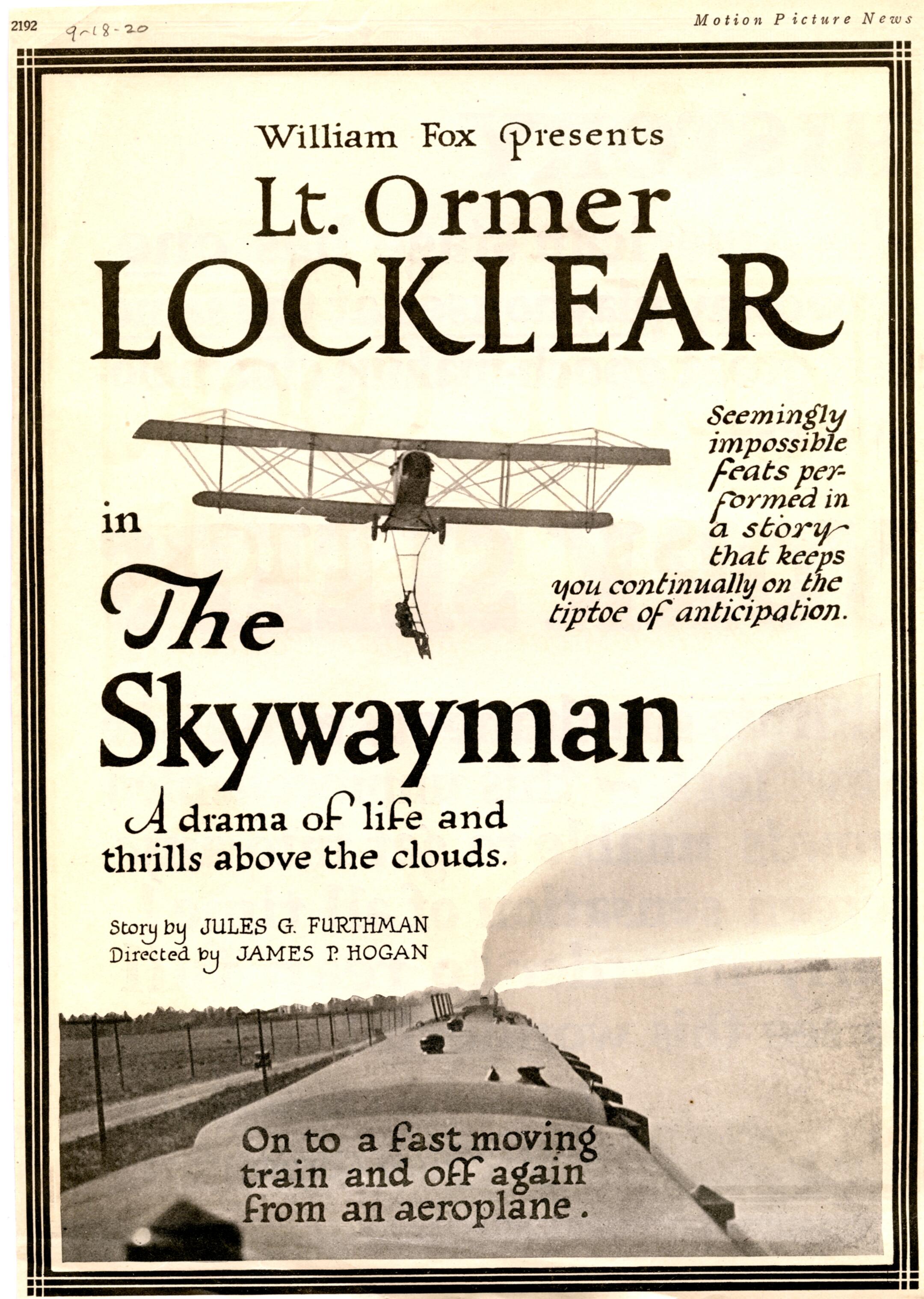

In 1928, a tragic accident during filming made history in Hollywood. Ormer Locklear, a former Army Air Service pilot known for performing repairs while walking on airplane wings, started the Locklear Flying Circus after World War I. He quickly became a star thanks to a film called “The Great Air Robbery,” produced by Carl Laemmle. However, his second movie, “The Skywayman,” for William Fox, proved fatal. During a nighttime stunt, Locklear requested the field lights be turned off so he could time his pull-out from a dive. When the lights weren’t switched off, Locklear and his fellow pilot, Milton “Skeets” Elliott, crashed and were killed. (The crash was included in the final film, but no footage of it remains today.)

Hollywood historian Marc Wanamaker explains that a plane crash deeply affected pilot Paul Mantz, nicknamed “Denny,” inspiring him to develop safer methods for filming aerial stunts. He created a small, remote-controlled airplane – a precursor to modern drones – that was later used during World War II to train fighter pilots. This highlights the close relationship between the early days of Hollywood and the advancement of aviation.

According to Wanamaker, the first movies were really focused on capturing things in motion. It began with simple subjects like horses, then expanded to include trains and eventually airplanes.

The movie “Bright Eyes”—starring Shirley Temple as an orphaned girl taken in by her father’s pilot buddies—was part of a wave of films that showcased and glorified the excitement of air travel and the wonder of flying.

Following World War I, flying became incredibly popular, capturing the imagination of everyone – including women – and Hollywood played a big part in fueling that excitement. Comedians like Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy made films about aviation, and even the famous magician Harry Houdini appeared in a flying-themed movie called “The Grim Game.” Stars like Rudolph Valentino and Mary Pickford also learned to fly, and Ruth Roland became known as the leading lady of stunt flying films. In fact, both women owned their own airplanes, and Pickford famously brought a unique “dragon” plane to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre for a memorable publicity photo.

When celebrities started flying, they announced their travel plans so photographers could get pictures of them arriving and departing, clearly showing the airline they were using. Many posed with their private planes or at airport terminals, and some even dressed in aviation-themed outfits, like hats shaped like airplanes. Costume designers like Howard Greer and Jean Louis created stylish uniforms inspired by flight attendants.

Camouflaging an airport

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hollywood designers cleverly camouflaged Burbank Airport (then known as Lockheed Air Terminal) to blend it into the surrounding neighborhoods. Originally opened in 1930 as United Airport, Burbank quickly became a rival to Glendale as a hub for both air travel and celebrity spotting – long before Los Angeles International Airport, which was then a small airfield called Mines Field surrounded by farmland, became prominent.

In 1940, Lockheed bought United Airport and, after the U.S. entered World War II, began using it to manufacture and prepare military planes. Worried about potential attacks on the West Coast by Japan, the military asked Hollywood studios to help disguise Lockheed’s facilities.

As a film buff, I was absolutely fascinated to learn about the incredible lengths Lockheed Martin went to during WWII to camouflage their aircraft factory. Apparently, they brought in designers from the biggest movie studios – Disney, Paramount, and 20th Century Fox – to create a massive, 1,000-acre cover over the entire facility. The goal was to make it completely blend in with the surrounding neighborhood. They didn’t just throw up a tarp, either. It was a really elaborate setup using chicken wire, netting, and painted canvas to mimic the grass. And get this – they even built fake trees, using spray-painted chicken feathers as leaves! Some were bright green to look fresh, and others were brown to simulate dead patches – a seriously convincing illusion.

As a lifelong film buff, I always knew Burbank was vital to Hollywood, but I recently learned why it was so crucial during the war. Apparently, they ran something called Operation Camouflage, and it worked brilliantly – Burbank’s Lockheed Airport was never hit by bombs! It’s amazing when you think about it, because even after LAX opened in 1979, the frequent coastal fog often meant planes had to divert and land at Burbank instead. So, it wasn’t just a studio town; it was a critical backup landing spot, and thankfully, it stayed safe.

LAX also has a connection to Hollywood’s past. Before it was LAX, the land, then called Mines Field, was where actors like Jimmy Stewart, Tyrone Power, and Robert Taylor took flying lessons back in 1937. Since then, LAX has appeared in many forms of media – from the iconic opening of the film “The Graduate” to the lyrics of Miley Cyrus’ song “Party in the U.S.A.” Interestingly, while the 2024 Netflix movie “Carry-On” is set at LAX, it was actually filmed at an old terminal in New Orleans.

Despite challenges in both the entertainment and airline industries, they continue to support each other. Celebrities still promote airlines and are frequently photographed traveling, and compelling airport scenes remain a popular cinematic trope. Ultimately, both movies and flying still represent excitement and new opportunities.

Read More

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang (MLBB) Sora Guide: Best Build, Emblem and Gameplay Tips

- Clash Royale Best Boss Bandit Champion decks

- Brawl Stars December 2025 Brawl Talk: Two New Brawlers, Buffie, Vault, New Skins, Game Modes, and more

- Best Hero Card Decks in Clash Royale

- All Brawl Stars Brawliday Rewards For 2025

- Best Arena 9 Decks in Clast Royale

- Clash Royale December 2025: Events, Challenges, Tournaments, and Rewards

- Call of Duty Mobile: DMZ Recon Guide: Overview, How to Play, Progression, and more

- Clash Royale Witch Evolution best decks guide

- Clash Royale Best Arena 14 Decks

2025-12-01 14:32