Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are exploring how to harness the power of biological communication to create robust and adaptable networks for the Internet of Bio-Nano Things.

This review details a neural-inspired molecular communication framework leveraging criticality and reservoir computing to enhance collective intelligence in multi-agent nanonetworks.

Conventional approaches to nanoscale communication often demand complex transceiver architectures incompatible with the energy and processing limitations of realistic nanomachines. This challenge motivates the work presented in ‘Neural-Inspired Multi-Agent Molecular Communication Networks for Collective Intelligence’, which proposes a paradigm shift toward collective intelligence inspired by cortical networks. By modeling a decentralized network of simple nanomachines communicating via diffusion with a threshold-based firing mechanism-specifically, the Greenberg-Hastings model-we demonstrate that information transfer is maximized at a critical transition point, mirroring the edge of chaos observed in biological systems. Could this bio-inspired approach unlock scalable and robust communication for the Internet of Bio-Nano Things and beyond?

The Inevitable Drift: Redefining Nanoscale Communication

Conventional nanonetwork designs frequently prioritize mathematical tractability over biological realism, resulting in models that operate under highly simplified assumptions. These often involve treating nanomachines as ideal transmitters and receivers, neglecting the complexities of molecular noise, diffusion dynamics, and energy constraints inherent in nanoscale communication. Consequently, current models struggle to accurately predict performance in realistic scenarios, particularly when dealing with large-scale networks or complex information encoding schemes. This limitation hinders the development of nanonetworks capable of truly sophisticated information processing, prompting a re-evaluation of fundamental design principles and a move towards bio-inspired approaches that embrace the inherent complexities of biological communication systems.

The intricate communication within biological systems, particularly the cerebral cortex, presents a powerful model for nanonetwork design. Cortical networks achieve remarkable robustness and efficiency not through centralized control, but via massively parallel, decentralized processing – billions of neurons communicating through complex synaptic connections. This architecture inherently tolerates node failures and adapts to changing conditions, a stark contrast to many current nanonetwork protocols vulnerable to single-point failures or limited bandwidth. By mimicking the principles of synaptic plasticity, neuronal coding, and spatiotemporal signaling observed in cortical circuits, researchers aim to create nanonetworks capable of handling complex information with greater resilience, adaptability, and energy efficiency than traditionally engineered systems. This bio-inspired approach suggests a future where nanonetworks can dynamically reconfigure themselves, learn from their environment, and maintain functionality even in the presence of significant disruption – mirroring the brain’s own remarkable capacity for self-repair and continuous operation.

Current nanonetwork designs frequently prioritize simplicity, often at the expense of processing power and adaptability. Researchers are now advocating for a fundamental shift in approach – embracing molecular communication inspired by the intricate signaling networks found within the brain. This bio-inspired paradigm moves beyond traditional electrical signaling to utilize molecules as information carriers, mirroring the way neurons communicate via neurotransmitters. By adopting principles from neuroscience, such as decentralized processing and synaptic plasticity, these emerging nanonetworks aim to achieve enhanced robustness, scalability, and energy efficiency. The resulting systems promise a significant leap forward in nanodevice communication, potentially enabling complex distributed computations and highly resilient data transmission in environments where conventional methods falter.

Simulating the Collective: Agent Behavior and Network Topology

The Greenberg-Hastings model, utilized to simulate agent behavior, represents each molecular agent with a binary state: either ‘off’ or ‘on’. This model defines the probability of an agent transitioning from ‘off’ to ‘on’ as a function of the cumulative input it receives from neighboring agents. Specifically, the transition probability is calculated using a sigmoidal function [latex]f(x) = 1 / (1 + e^{-x})[/latex], where ‘x’ represents the net input. When an agent transitions to the ‘on’ state, it emits a signal, representing molecular release, and subsequently returns to the ‘off’ state after a refractory period, effectively modeling temporal dynamics and preventing sustained activation. This discrete-state approach simplifies computational complexity while capturing essential features of neuronal signaling applicable to our molecular agent network.

Each agent in the network operates on a threshold-based firing mechanism; stimulation increases the agent’s internal state, and upon reaching a predefined threshold, the agent releases a fixed quantity of molecules into its surrounding environment. This process mimics synaptic transmission in biological neurons, where a sufficient electrochemical signal triggers the release of neurotransmitters. The threshold value represents the sensitivity of the agent to incoming signals, while the released molecules act as signals to neighboring agents. The magnitude of stimulation is directly proportional to the number of received molecules, creating a feedback loop that regulates agent activity and network dynamics. This mechanism allows for both amplification and filtering of signals within the network, contributing to its overall responsiveness and stability.

The network’s architecture is fundamentally decentralized, meaning each agent functions as both a transmitter and a receiver of molecular signals. This bidirectional capability eliminates single points of failure and enhances robustness; the failure of any individual agent does not critically disrupt overall network function due to continued signaling via alternative pathways. Furthermore, this distributed model directly supports scalability; adding more agents does not necessitate a central coordinating entity or dramatically increase the computational burden on existing agents. Each new agent simply integrates into the existing communication web, extending the network’s capacity without compromising its resilience or requiring substantial architectural modifications. This contrasts with centralized architectures where performance bottlenecks and failure risks increase proportionally with network size.

The spatial distribution of agents within the network is established using a Poisson Point Process. This probabilistic model generates random points in space, with each agent’s location determined independently of others, based on a uniform rate λ. Employing a Poisson Point Process ensures a homogeneous network topology, characterized by a consistent average agent density across the simulation space and the absence of clustering. The parameter λ directly controls this density; a higher value results in a greater number of agents distributed uniformly throughout the defined area. This approach avoids artificial patterns or biases in agent placement, promoting realistic and scalable network behavior.

Decoding the Signal: Analytical Tools for Network Characterization

Mean-Field Analysis simplifies the complex interactions within a network by approximating the behavior of individual nodes based on the average influence of their neighbors. This approach transforms a potentially intractable many-body problem into a series of self-consistent equations describing the aggregate behavior. Fixed-Point Iteration is then employed as a numerical technique to solve these equations, iteratively refining the approximation until a stable solution – a fixed point – is reached. This method efficiently determines the network’s overall state, such as the average signal strength or the probability of successful communication, without requiring detailed tracking of every individual node’s dynamics. The computational efficiency of this combined approach allows for rapid performance evaluation under varying network parameters and conditions.

The channel impulse response (CIR) describes the time-domain characteristics of a channel’s effect on a transmitted signal. In the context of free diffusion, the CIR is governed by the diffusion process, resulting in a broadening of the signal over time and a corresponding decrease in amplitude. Specifically, the CIR’s shape is determined by the diffusion coefficient and the time elapsed since transmission; a higher diffusion coefficient or longer transmission time leads to greater signal dispersion and attenuation. This time-spreading effect causes inter-symbol interference (ISI), distorting the received signal and limiting the maximum achievable data rate. The CIR is mathematically represented as [latex] h(t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{4Dt}} [/latex], where D is the diffusion coefficient, t is time, and x represents spatial displacement.

Signal detection is characterized by a fully absorbing receiver model, meaning any signal reaching the receiver is completely absorbed, with detection determined by the cumulative signal strength exceeding a defined threshold. This model, combined with the assumption of a Gaussian distribution for the received signal strength, allows for probabilistic analysis of detection events. The Gaussian distribution is parameterized by the mean signal strength and the variance of noise and interference, enabling calculation of the probability of detection and false alarm rates. Specifically, the probability density function of the received signal [latex] p(x) = \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}} [/latex] is used, where μ represents the mean and σ the standard deviation of the received signal.

Performance prediction across varying network conditions is achieved through the combined application of Mean-Field Analysis, channel impulse response modeling, and a fully absorbing receiver model. The accuracy of these predictions is rigorously verified using Fixed-Point Iteration, continuing until a tolerance threshold of 10-12 is met. This level of precision ensures that the iterative process converges on a stable solution, allowing for reliable estimation of key performance indicators – such as signal detection probability and network capacity – under diverse operational scenarios. The chosen tolerance represents a balance between computational cost and the desired degree of accuracy in the performance assessment.

Harnessing Instability: Emergent Computation at the Edge of Chaos

The nanonetwork’s computational efficacy stems from its operation at the ‘edge of chaos’, a dynamic regime balancing order and disorder. This critical state, observed through detailed analysis, isn’t simply instability; rather, it represents a point of maximized information processing potential. At this threshold, the network exhibits heightened sensitivity to input signals and a remarkable capacity to adapt and respond to complex stimuli. Unlike rigidly ordered systems, which lack flexibility, or completely chaotic systems, which are unpredictable, the edge of chaos allows for both robust signal transmission and the emergence of novel computational abilities – essentially, the network can perform complex tasks without being explicitly programmed to do so, leveraging the inherent dynamics of its interconnected components.

Inter-Symbol Interference (ISI), typically considered a detrimental effect in communication systems, can surprisingly enhance signal detection when harnessed through a phenomenon known as Stochastic Resonance. This counterintuitive principle suggests that the addition of a specific level of noise to a weak signal can actually make it more detectable. In nanonetworks, where signal strength is often limited and noise is pervasive, ISI creates a form of constructive interference when carefully balanced with added noise. This balance effectively amplifies the desired signal, improving the reliability of communication. The system doesn’t eliminate interference, but rather exploits it, turning a potential hindrance into a beneficial mechanism for boosting signal clarity and maximizing information transfer even in challenging environments.

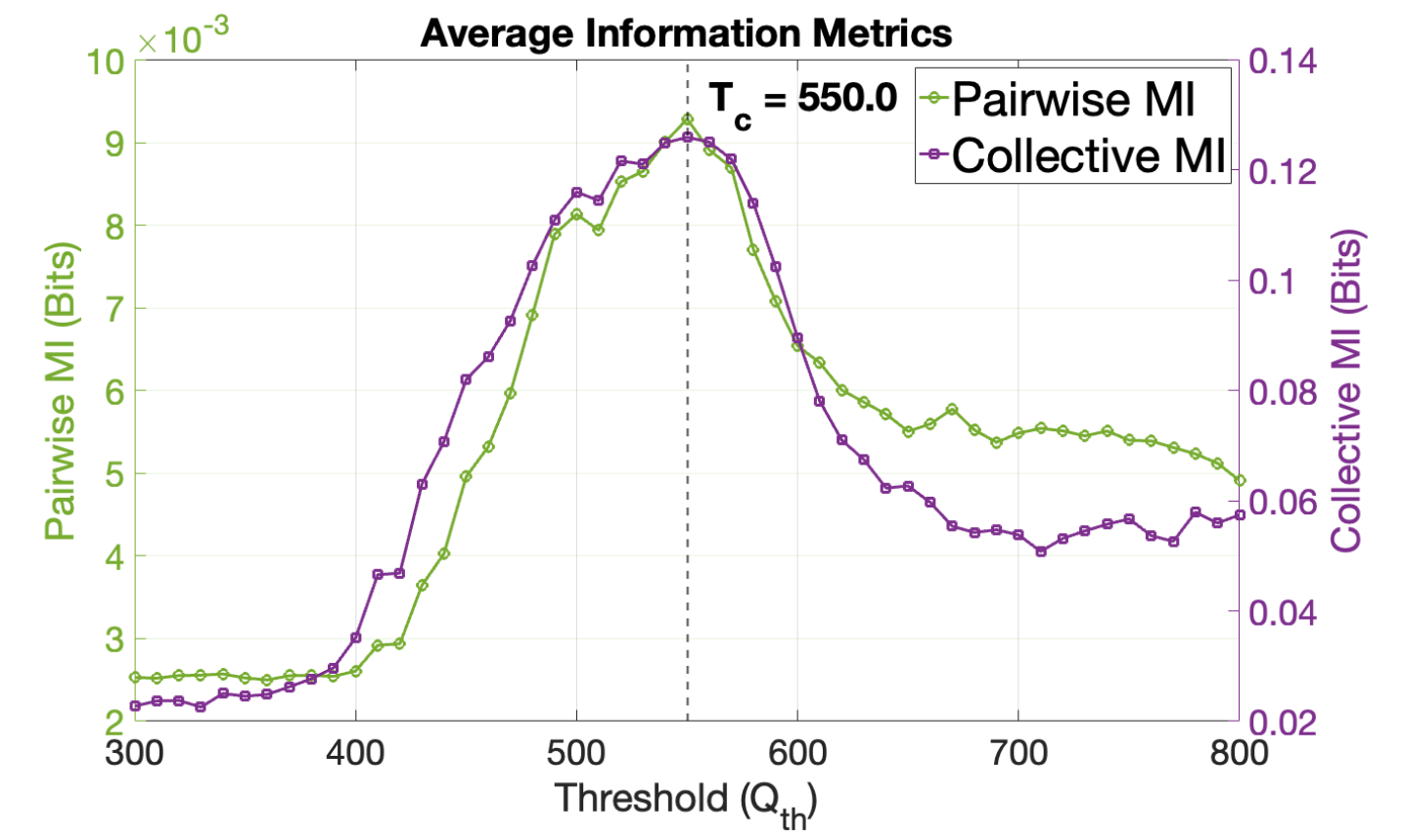

The network’s communication capacity is rigorously quantified through the measurement of Mutual Information, a metric that reveals the amount of information shared between individual agents within the system. Analysis demonstrates this information transfer isn’t simply present, but exhibits a distinct peak at an activation threshold of 500 units; this suggests an optimal level of network activity where communication is maximized. Below this threshold, information exchange is limited, while exceeding it leads to diminishing returns, indicating a critical point for efficient data propagation. This finding underscores the network’s capacity for complex communication and its ability to effectively process and transmit information when operating at this precisely defined activation level.

Inspired by the principles of Reservoir Computing, this nanonetwork framework demonstrates a capacity for performing complex information processing tasks by exploiting a carefully tuned dynamic regime. The system doesn’t rely on traditional, pre-programmed algorithms, but instead leverages the inherent, rich dynamics of the network itself as a computational resource. By operating at a critical point – the ‘edge of chaos’ – information propagation is maximized, allowing signals to be effectively processed and transmitted throughout the nanonetwork. This approach opens possibilities for implementing sophisticated functions, such as pattern recognition and data filtering, within extremely small-scale devices, potentially revolutionizing fields like biosensing and distributed computing, all achieved without the need for complex, power-hungry control mechanisms.

The pursuit of collective intelligence, as demonstrated in this exploration of molecular communication networks, echoes a fundamental principle of existence: systems inevitably trend towards entropy. This research, by leveraging the principles of criticality and reservoir computing, attempts to momentarily suspend that decay, creating pockets of enhanced information transfer. As Albert Einstein once observed, “The important thing is not to stop questioning.” This relentless pursuit of understanding, mirrored in the design of these bio-inspired networks, suggests an acknowledgement that even in the face of inevitable decline, innovation offers fleeting moments of temporal harmony – a temporary resistance to the universal pull towards disorder. The study implicitly recognizes that maintaining ‘uptime’, so to speak, is not about permanence, but about skillfully navigating the inherent ephemerality of complex systems.

The Horizon Beckons

The pursuit of collective intelligence within bio-nano networks, as demonstrated by this work, inevitably confronts the limitations inherent in any complex system. The architecture presented-drawing inspiration from biological signaling-hints at robustness, yet remains tethered to the fragility of its constituent nanomachines. Every delay in material science-in refining signal transduction, enhancing longevity, or minimizing noise-is the price of understanding. The current model, operating at the edge of criticality, offers a promising pathway, but scaling such a system demands confronting the inevitable drift from that ideal regime. Maintaining criticality is not a static achievement; it is a dynamic equilibrium constantly challenged by entropy.

Future efforts will likely necessitate a deeper exploration of the interplay between network topology and the nuances of the Greenberg-Hastings model. A truly adaptive network will require mechanisms for self-repair and recalibration, moving beyond pre-programmed responses. Moreover, the translation of reservoir computing principles to this molecular domain necessitates addressing the inherent limitations of molecular computation-the trade-off between complexity and reliability. Architecture without a considered history-without acknowledging the inevitable decay-is fragile and ephemeral.

The long view suggests a shift from simply maximizing information transfer to optimizing for useful information. A network that can discern signal from noise, prioritize relevant data, and adapt its communication strategy based on environmental context will be far more valuable than one that merely achieves high bandwidth. The ultimate challenge lies not in replicating intelligence, but in cultivating resilience-in building systems that age gracefully, adapting to the inevitable pressures of time.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.18018.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Star Wars Fans Should Have “Total Faith” In Tradition-Breaking 2027 Movie, Says Star

- Jessie Buckley unveils new blonde bombshell look for latest shoot with W Magazine as she reveals Hamnet role has made her ‘braver’

- eFootball 2026 is bringing the v5.3.1 update: What to expect and what’s coming

- Call the Midwife season 16 is confirmed – but what happens next, after that end-of-an-era finale?

- Taimanin Squad coupon codes and how to use them (March 2026)

- Denis Villeneuve’s Dune Trilogy Is Skipping Children of Dune

- Country star Thomas Rhett welcomes FIFTH child with wife Lauren and reveals newborn’s VERY unique name

- Decoding Life’s Patterns: How AI Learns Protein Sequences

- Robots That React: Teaching Machines to Hear and Act

- Mobile Legends: Bang Bang 2026 Legend Skins: Complete list and how to get them

2026-01-27 22:38